CONTRACT LECTURES TRANSCRIPTS

advertisement

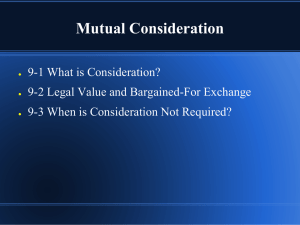

CONTRACT LECTURES TRANSCRIPTS C STRICKLAND LECTURE 5 Total time = 59 mins and 41 seconds Track/slide 1 01.07 Introduction We are continuing with consideration and are now looking at whether it is possible to establish a NEW CONTRACT using consideration from an EXISTING CONTRACT. In other words, can consideration be MULTI-APPLICABLE? To recap, we said that we can look at this under the traditional 3 headings – is there SUFFICIENT CONSIDERATION to make ANOTHER contract in the: i. performance of a PUBLIC or STATUTORY duty? ii. performance of a contractual duty ALREADY OWED to a 3rd party? iii. performance of an ALTERATION to an existing contractual duty? The first two headings have been addressed in lecture 4. We can now continue by discussing the issues that arise under heading number 3. Track/slide 2 04.14 Here, then, we begin our discussion of the situation WHERE THERE IS A MAIN CONTRACT AND THEN ONE SIDE SUGGESTS AN 'ALTERATION’ promising either to PAY MORE for the same work under the original contract or to ACCEPT LESS PAYMENT than is due under the original contract are such alteration promises enforceable as contracts? Is there consideration for them? We need to look at both possibilities. Promises to PAY MORE for the same work Key cases that we need to look at here are: Stilk v Myrick 1809 Hartley v Ponsonby 1857 and Williams v Roffey Brothers & Nicholls (contractors) Limited 1991 The leading case here until 1991 was STILK v MYRICK 1809. However, the rule in this case was EFFECTIVELY OVERRULED in 1991 by the extremely important case of WILLIAMS v ROFFEY BROS LTD. We can now look at these 3 cases. In STILK v MYRICK it was held that a promise by the master of a ship to pay the crew EXTRA money above that already agreed for sailing the ship home in an emergency was UNENFORCEABLE by the crew as they had provided NO EXTRA CONSIDERATION for the extra money. When the boat had reached Cronstadt, 2 of the sailors deserted and the master had promised the crew that if they sailed the ship back to London he would divide the wages of the deserters between them. He did not do so and one sailor sued. There are 2 reports of this case, the Espinasse report that says that the case was decided on the issue of duress for public policy reasons, and the Campbell report, that says the case was decided on the basis that ‘legally’ the sailors had not provided consideration because by sailing the boat home in an emergency they were merely doing what they originally were contracted to do. In Hartley v Ponsonby 1857 the result was different because the sailors provided consideration by doing ‘more’ than they were originally contracted to do. In this case there was an original crew of 36 sailors and 17 deserted leaving only 19, of which only 4 or 5 were able seamen. The master of the ship promised the 19 remaining crew members extra wages if they sailed the ship home. Were they entitled to the extra wages? Yes – when the 17 deserted, the ship was so undermanned that they were not legally obliged to sail her back under the original contract. In effect, the contract was frustrated. Agreeing to sail back for enhanced wages was the consideration for a new contract. They were doing more than they were originally required to do. Track/slide 3 02.38 In WILLIAMS v ROFFEY the defendant building contractors had entered into a contract with a sub-contractor for the carpentry work on the block of 27 flats for a price of £20,000. After the sub-contractor had completed about 80% of the work and received interim payments for this, it became clear to the main contractor that the sub-contractor was in grave financial difficulties, mainly because he had under-priced his bid for the job, and there was a danger that he might pull out of the work. The main contractor was under the threat of a penalty clause if he did not complete the whole refurbishment of the 27 flats on time and so he called a meeting with the carpenters and promised to pay them extra money ‘on completion’ of each flat. When the carpenters had completed a further 8 flats they had received only one extra payment from the main contractor and so stopped work and sued for the other payments. The main contractor said that they were not entitled to any extra money because the ALTERATION to pay this extra money was UNENFORCEABLE AS IT LACKED CONSIDERATION by the carpenters. It was held in Court of Appeal that the carpenters were entitled to the extra payments because they had provided consideration to the main contractors for their promise in that: the promise secured completion of the work on time so that the main contractors avoided the penalty clause, and, the main contractors avoided the need to employ another sub-contractor if the original ones decided to quit. This is such an important case and you MUST ALL READ IT IN THE LAW REPORTS. It is a relatively short case but very important. Track/slide 4 02.20 Although the 3 Lords justices of appeal all agreed with the result, they got there by different routes. We can briefly look at the judgments of each of them, starting with Glidewell LJ: His lordship provides a good survey of relevant case law and is of the view that the doctrine of PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL (which we look at next) does NOT APPLY in this case. His lordship further notes that in some cases, the doctrine of ECONOMIC DURESS might apply though not in this case. This would be where the PLAINTIFF had stopped doing work and WAS DEMANDING extra payment for completing – in the present case the plaintiff, the sub-contractors were not the ones who suggested the extra payment – that idea came from the main contractors so they couldn’t try to use economic duress or fraud as an argument. His lordship decides the case on the basis of how he sees the law to be as stated in PAO ON v LAU YIU1979 - basically that the promise by the main contractors to pay extra to avoid a penalty and to get the work done by the original subcontractors gave them a PRACTICAL BENEFIT or avoided a DISBENEFIT to them and this was consideration – so long as economic duress or fraud was absent. His lordship further said that STILK v MYRICK was NOT OVERRULED by his judgment that he was merely ‘REFINING AND LIMITING’ the application of the case. Track/slide 5 01.18 We can now look at the judgment of Russel LJ: His lordship said that he would have been happy to consider the doctrine of PROMISSORY ESTOPPEL in this case HAD counsel for the main contractors raised it – and gives a good explanation of how it applies. He then moves on to base his finding of consideration on a PRAGMATIC view of it – he states ‘Consideration there must still be but in my judgment the courts nowadays should be more ready to find its existence so as to REFLECT the INTENTION OF THE PARTIES to the contract where the bargaining powers are not unequal and where the finding of consideration reflects the true intention of the parties’. His lordship also confirms the point that in no way does his judgment affect the standing of STILK v MYRICK which is still good law. Track/slide 6 01.18 We can now look at the judgment of Purchas LJ. His lordship starts off by saying that STILK v MYRICK is still good law and that his judgment does not effect it. His lordship expresses the view that the Stilk v Myrick case was in large part decided for POLICY reasons – to protect masters of ships from being held to ransom by crews at sea. And he suggests that the lack of consideration argument was only really used because the duress was not available. His lordship felt that there was consideration in this case for COMMERCIAL REASONS – as the sub-contractor could have decided to be in deliberate breach of contract in order to ‘cut his losses’. And so if BOTH PARTIES ‘BENEFIT’ from an agreement it is not necessary that both should also suffer a detriment for consideration to exist. Track/slide 7 02.19 We can consider some commentary on this case: After the case, commentators wondered to what extent the whole idea of consideration had been NULLIFIED – since there seemed to be no real consideration for the extra payment – so although their lordships stressed that they were not challenging the decision in Stilk v Myrick, in effect they overruled it. It is interesting to note that all 3 lord justices of appeal stressed the fact that their judgments only applied to ALTERATION PROMISES and had NO EFFECT AT ALL on the requirement to find consideration in THE FORMATION OF CONTRACTS from scratch. Thus the requirement for consideration in the formation of contracts seems to be intact after this case – as supported in RE SELECTMOVE 1995 and RE C(A DEBTOR) 1994. In addition, the move away from the need for ‘legal’ consideration in Williams v Roffey Brothers Limited 1991 was NOT FOLLOWED in recent cases concerning promises to ACCEPT LESS payment than is due under an original contract. Remember that in Williams v Roffey, the consideration that was said to exist was of a ‘practical’ or ‘factual’ nature as opposed to really ‘legal’ in nature. As we shall see shortly, Williams v Roffey Bros Limited has made NO IMPACT on the old cases of PINNEL 1602 and FOAKES v BEER 1884. Track/slide 8 02.24 We can now move on to consider PROMISES TO ACCEPT ‘LESS PAYMENT’ THAN IS DUE UNDER AN ORIGINAL CONTRACT The leading cases here are PINNEL’S CASE 1602 and FOAKES v BEER 1884. In PINNEL’S CASE it was held that if A made a promise with B to accept LESS PAYMENT for a debt and NOT TO SUE for the balance, then this agreement was UNENFORCEABLE unless B gave some extra consideration for it. The consideration given, however, could be determined by A and B – thus even ‘payment in kind’ could be enough (such as ‘a horse, a hawk or a robe’). In Pinnel’s case, Pinnel had accepted less money from Cole than he was owed, over a month in advance of the due date – on October 1st instead of on 11th November. Pinnel had accepted this as full satisfaction for the debt. However, Pinnel sued Cole for the remainder of the debt. Pinnel only succeeded on a technical point of pleading because although it was held that ‘Payment of a lesser sum on the due day for a debt is no satisfaction of the debt’ (and so the creditor can sue for the rest) payment of a lesser sum may be enough to discharge the debt where the circumstances of paying less can be regarded as creating extra consideration to the benefit of the creditor as follows: Track/slide 9 02.23 i. payment in kind rather than in money (as the ‘thing in kind’ might be of more use to the creditor than the money) ii. payment in advance of the due date (in Pinnel’s case, Cole would have won the case had it not been for the technical point because by paying in advance there would have been sufficient consideration – benefit to Pinnel ) iii. payment at a different location to the creditor’s advantage ( such that the debtor has to travel and incur expenses to get to the new location) iv. payment of a lesser sum by a third party accepted as full settlement by the creditor (to avoid fraud against the third party). See HIRACHAND PUNAMCHAND v TEMPLE 1911. In this case, a father wrote to the plaintiffs, his son’s creditors, offering to pay part of a debt on a promissory note in satisfaction of the whole debt, and he enclosed a draft for that amount. The plaintiffs cashed the draft, and then sued the son for the balance. The Court of Appeal held that there was sufficient consideration, benefit to the plaintiff, to discharge the whole debt that was owed by the son, a Lieutenant Temple. v. agreement by a group of creditors (composition of creditors) that they will accept less than is actually owed them – should one creditor then try to sue to get the full amount owed, this could be seen as fraud against the other creditors. Track/slide 10 03.00 We can now move on to consider the case of Foakes v Beer 1884. This case is very important because it confirmed Pinnel’s case in the House of Lords. In this case Mrs Beer had obtained a judgment against Dr Foakes for £2090 – 19shillings. The key point is that such judgments carry INTEREST from the date of the judgment. In an agreement with Dr Foakes Mrs Beer promised to accept payment by way of a £500 down payment and regular instalments of £150. When all the debt was paid, as scheduled and thus on the due dates, she sued him for the interest. The House of Lords held that she could claim the interest from Dr Foakes because although in the agreement between her and Dr Foakes she had stated that she WOULD NOT take proceedings to enforce the debt, this agreement LACKED CONSIDERATION by Foakes – he had to pay the debt to her anyway as scheduled and so he gave no additional consideration for her to accept LESS than she was due, which was the DEBT PLUS INTEREST. This case has been criticised and it is difficult to reconcile it with Williams v Roffey Bros Limited 1991. In Foakes v Beer, Mrs Beer certainly obtained a benefit from the getting the debt paid in instalments – the option might have been to get no payment at all. So why couldn’t this have been seen as conferring a PRACTICAL BENEFIT to Mrs Beer not only in FACT but also in LAW by acknowledging it as consideration? This is the approach that was taken in Williams v Roffey – the main contractor got a practical benefit, not a ‘legal’ benefit directly, although the net result was that the ‘practical’ or ‘factual’ benefit was recognised as a ‘legal’ benefit. Track/slide 11 02.33 However, Foakes v Beer does stand as good authority, being a House of Lords case, as shown in the case of RE SELECTMOVE LIMITED 1995. In this case Foakes v Beer was followed and Williams v Roffey Brothers Limited was distinguished. The case is useful for confirming a few rules of contract law, namely that: SILENCE DOES NOT AMOUNT TO AN ACCEPTANCE OF AN OFER (in this case the agent did not have authority to say silence was an acceptance) and that the rule in Faokes v Beer was still good law. It also added that: Williams v Roffey Brothers Limited only applies to contracts involving GOODS AND SERVICES - NOT TO CASES OF PURE DEBT PAYING. Thus, since the present case was a pure payment of debt case (a company owing tax and National Insurance Contributions to the inland revenue) an agreement by the inland revenue to accept payment in installments from the company was unenforceable due to lack of consideration. Thus, Williams v Roffey Brothers Limited was given a NARROW RATIO DECIDENDI– so that it could only apply to contracts for goods and services. In this way, the rule in F v B was not challenged which would have been impossible anyway as it was a House of Lords case and Re Selectmove was only in the Court of Appeal – thus it would have been against the rules of precedent to attempt to overrule Foakes v Beer. This point is explored on the Butterworths copy of the case at page 7 per Peter Gibson LJ. Track/slide 12 02.03 Having looked at many of the issues surrounding the doctrine of consideration in contract formation and in alteration promises made on the back of original contracts, it is now necessary to move on to consider an associated doctrine, that of Promissory Estoppel. As we shall see, where there is an alteration promise following on from an original contract, if it is not possible to say that this alteration promise is legally enforceable in a court because as an alteration promise it lacks extra consideration over and above that given for the original contract, then it might be possible to argue that the alteration promise is enforceable despite the lack of consideration due to the equitable doctrine of promissory estoppel. We shall also see that as a doctrine it has severe limitations, not least of which is that it is generally only available as a defence and is not a cause of action in its own right. A possible definition of Promissory Estoppel can be found in the McKendrick text book, ‘Contract Law – text, cases and materials’, published by Oxford Press, on page 113, where he states: ‘where by words or conduct a person makes an unambiguous representation as to his future conduct, intending the representation to be RELIED on and to affect legal relations between the parties, and the representee alters his position in reliance on it, the representor will be unable to act inconsistently with the representation if by so doing the representee would be prejudiced’. Track/slide 13 04.48 First, it is a good idea to make a few early points 1. The reason we are studying promissory estoppel is because it has the POTENTIAL to REPLACE CONSIDERATION as a key requirement for the FORMATION of a contact. As it stands, Promissory Estoppel has NOT replaced the requirement for consideration in the FORMATION of contracts BUT it has been used as a device to ENFORCE PROMISES MADE IN RELATION TO EXISTING CONTRACTS – when these new promises are NOT supported by NEW consideration. It is thus a way of AVOIDING the need to find consideration in order to make a promise legally enforceable. 2. Promissory Estoppel is just one type or strand of a broader equitable principle of estoppel. In Williams v Roffey Brothers Limited 1991, Russel LJ quoted a passage from the Amalgamated Investment and Property Co case 1982 in which Lord Denning MR stated: ‘The doctrine of estoppel is one of the most flexible and useful in the armoury of the law. But it has become overloaded with cases. That is why I have not gone through them all in this judgment. It has evolved during the last 150 years in a sequence of separate developments: proprietary estoppel, estoppel by representation of fact, estoppel by acquiescence and promissory estoppel. At the same time it has been sought to be limited by a series of maxims: estoppel is only a rule of evidence: estoppel cannot give rise to a cause of action: estoppel cannot do away with the need for consideration, and so forth. All these can now be seen to merge into one general principle shorn of limitations. When the parties to a transaction proceed on the basis of an underlying assumption (either of fact or of law, and whether due to misrepresentation or mistake, makes no difference), on which they have conducted the dealings between them, neither of them will be allowed to go back on that assumption when it would be unfair or unjust to allow him to do so. If one of them does seek to go back on it, the courts will give the other such remedy as the equity of the case demands’. Here we can see the hallmarks of promissory estoppel that will be revealed in our study of key cases below. 3. A contract (based on Offer, Acceptance, Consideration and Intention to create legal relations ) gives both parties to it a CAUSE OF ACTION – the right to take the other side to court for breach of contract. Promissory Estoppel does NOT give the aggrieved person a cause of action – the aggrieved person cannot take the other person to court for breach of a promise not supported by consideration. See the case of Combe v Combe 1951. 4. The essential difference between contracts supported by consideration and LATER PROMISES based on the original contract is that: When there is a CONTRACT - this protects the parties’ FUTURE EXPECTATIONS as most contracts are EXECUTORY – to be fulfilled in the future. Thus, there might be a cause of action without actual reliance on the contents of the contract by either side. However, Promissory estoppel - only protects people who have ACTUALLY RELIED on the promise, usually, though not always, to their detriment. Thus, the scope of application of promissory estoppel is narrower than the scope of application for contracts. Track/slide 14 03.39 Before looking at some of the key cases, we can now look at the general principles about Promissory Estoppel. When wishing to rely on promissory estoppel the following 6 points must be borne in mind. i. the promise in question MUST BE CLEAR – and is usually an EXPRESS PROMISE. The promise must clearly demonstrate that the promisor was giving up his strict legal rights viz a viz the promisee. ii. you will not be able to rely on Promissory Estoppel if it would be inequitable for you to do so – see D & C Builders v Rees 1966 – he who comes to equity must do so with clean hands. iii. usually the person trying to rely on estoppel must be able to show that they have SUFFERED A DETRIMENT by RELIANCE on the promise – that they altered their position in reliance on the promise – iv. promissory estoppel may either SUSPEND the original contractual position or completely EXTINGUISH it. It is usually only suspended. The contractual position was regarded as merely suspended in the Hughes case that we consider below – the notice to effect repairs within 6 months was suspended during negotiations about the sale of the lease – once they finished Hughes could then have given the railway company 6 months notice to do the repairs. This was also shown in Tool Metal Manufacturing Co Ltd v Tungsten Electric Co Ltd 1955. In this case the company was able to re-instate the original contract after temporarily suspending its rights under the contract – but it was only allowed to do this AFTER it had given ADEQUATE NOTICE to the promissee that it was reverting to the original Contract. v. Promissory estoppel is generally thought of as a ‘SHIELD AND NOT A SWORD’ - see Combe v Combe 1951. Thus, it cannot give rise to a cause of action by itself. As such it usually operates as a defence to an action. vi. it must be explicitly pleaded in court to be considered – see Williams v Roffey Brothers Limited 1991. The main gist of what we are looking at here then is that if an original contract is followed by an alteration promise, then IF extra consideration is not forthcoming to support this alteration promise it is not enforceable – in which case Promissory Estoppel may be resorted to, though we have just noted it is not an ideal fall back. Track/slide 15 00.55 We can now look at the development and operation of the doctrine of promissory estoppel and we can do this through 7 key cases. Hughes v Metropolitan Railway Company 1877 Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd 1947 Combe v Combe 1951 Tool Metal Manufacturing Co Ltd v Tungsten Electric Co Ltd 1955 D & C Builders v Rees 1966 Williams v Roffery Brothers & Nicolls (contractors) Limited 1991 Baird Textile Holdings Ltd v Marks & Spencer plc 2001 Track/slide 16 03.10 First then we shall look at the HUGHES CASE 1877 In this case the railway company leased some property from Hughes. In the lease was a covenant requiring the lessee (the railway company) to do repairs on receiving notice to do so from the lessor. Hughes gave the company six months notice to do some repairs. The company responded by offering to sell back to Hughes their interest in the property contained in the lease. The 2 sides started negotiations but these broke down and more than six months from the original date of notice to do repairs, the railway company had not started to do any. Hughes thus claimed that the lease had been forfeited because the company had not done the repairs within 6 months from being given notice to do the repairs. The railway company claimed that there was a TACIT UNDERSTANDING or an IMPLIED PROMISE that the repairs need not be carried out if the negotiations were concluded successfully and that whilst they were going on, the period of 6 months notice would not start to run. The case went to the House of Lords where the existence of the implied promise was not doubted. The problem was that it was NOT SUPPORTED BY CONSIDERATION and so seemed to be unenforceable. The House of Lords however said that it was enforceable and the basis of this decision comes from the famous speech of Lord Cairns LC at 448: ‘It is the first principle upon which all Courts of Equity proceed, that if parties who have entered into definite and distinct terms involving certain legal results … afterwards by their own act or with their own consent enter upon a course of negotiations which has the effect of leading one of the parties to suppose that the strict rights arising under the contract will not be enforced or will be kept in suspense or held in abeyance, the person who might otherwise have enforced those rights will not be allowed to enforce them where it would be inequitable, having regard to the dealings which have thus taken place between the parties.’. In other words, equity provides a way of making promises on the back of an existing contract enforceable, despite the lack of new consideration for them. Track/slide 17 04.02 We can now look at the HIGH TREES CASE 1947 In this case, CLPT (Central London Property Trust) sued High Trees House Ltd (HTH) for FULL RENT for the last 2 quarters of 1945, on a test basis to see if there was a possibility to sue for full rent for the WHOLE DURATION OF THE WAR. Once the war had started and it had become very difficult to rent out flats, CLPT had agreed to only charge HTH half the usual rent on the 99 year lease for the block of flats, that is, £1,250 instead of £2,500 a year. This agreement to accept lesser rent was made in writing, though it did not specify the duration of the reduction in rent. There was no extra consideration by HTH for the agreement. So, how could HTH say that the promise to accept less payment for the original contract could be binding? HTH, the defendants, based their argument on 2 possible grounds, either: i. the landlords were ‘estopped’ from claiming the full rent or ii. the landlords were bound by their promise of a reduction in rent which was made with the intention that it should be binding and should be acted on and which was, in fact, acted on by the tenants. Denning J gave the judgment of the court. He held that the action should succeed so that CLPT could recover the full rent for the last 2 quarters of 1945, which is all that they were claiming. He decided the case on the basis of the second argument above, so his comments on estoppel were obiter dictum. However, the key importance of the case comes from these obiter remarks. He said that HAD CLPT sued for the full rent between 1940 and 1945 it would have been estopped from doing so because of the promise not to demand full rent. He relied on the Hughes case. Crucially for the situation when someone accepts a lesser sum in full satisfaction of a larger debt, as was the case here in the High Trees case, Lord Denning said that the PE argument ‘logically would extend to such a situation’. He said: ‘A party will not be allowed IN EQUITY to go back on such a promise… the logical consequence, no doubt, is that a promise to accept a smaller sum in discharge of a larger sum, if acted upon, is binding, notwithstanding the absence of consideration, and if the fusion of law and equity leads to that result, so much the better’. Although Dennings comments were obiter, Promissory Estoppel has been recognised in later cases, as we shall now see. Track/slide 18 05.47 We can now move on to the case of COMBE v COMBE 1951 In this case and husband and wife got divorced. The husband then promised to pay his wife £100 a year as a permanent allowance. In reliance on this promise, the wife did not apply to the courts for maintenance. When the husband failed to make the payments, she sued him on the promise. The Court of Appeal held that she could not succeed. There are 2 themes in the decision of the court: First, whether the wife’s ‘forbearance’ from applying to the Divorce Court for maintenance could amount to ‘consideration’ for the agreement to pay her £100 a year and Secondly, whether, if there was no consideration, could she rely on the principle of Promissory Estoppel as developed in the Hughes case. The Court of Appeal held: i. there was no consideration for the promise – in order for there to be consideration, her forbearance from going to the Divorce Court for maintenance must have been at the request of her husband either expressly or impliedly. In this way the court could have seen an exchange of promises. The Court held, per Denning LJ, that the husband had not expressly requested her forbearance from applying to the court for maintenance, and it could not be implied. As such the forbearance was not made in return for the promise by the husband. She may have suffered some ‘detriment’ by not going to the Divorce Court, but this detriment was not at the request of her husband, so was not consideration. ii. If no consideration, could she rely on promissory estoppel? NO. Denning LJ said at page 220: ‘Seeing that the principle (promissory estoppel) can never stand alone as giving a cause of action in itself, it can never do away with the necessity of consideration when that is an essential part of the cause of action. The doctrine of consideration is too firmly fixed to be overthrown by a side-wind. Its ill-effects have been largely mitigated of late, but it still remains a cardinal necessity of a formation of a contract, though not of its modification or discharge’. Lord Denning said that the wife could not use Promissory Estoppel here because her real cause of action was contract so she needed to find consideration and since there was none, she lost the case. This is why we have the phrase, promissory estoppel is a ‘SHIELD AND NOT A SWORD’. In other words, you can only use promissory estoppel with regard to contracts, on the back of an existing cause of action. The decision in Combe v Combe has been criticised. Could not the Court of Appeal have ‘implied’ that the husband promised her £100 a year in return for her promise not to go to the Divorce Courts? That her forbearance was thus ‘linked’ to the husband’s promise and could be consideration. There are 2 possible reasons why the court did not see her forbearance as consideration: i. ii. the case was essentially a Family law case – and she could not take away her own right to go to the Divorce courts for maintenance – so even if it was implied that she had promised not to go to the Divorce courts for maintenance in response to the husbands promise, it was not consideration because she could still have gone to the DC – her promise would thus have been worth nothing. The court would not imply that she had promised not to go to the Divorce courts in response to her husband’s promise because the ‘justice of the case’ did not require it. This is because she was earning more than her husband and had not asked for £100 after the first non-payment, but had waited 6 years and was after a lump sum of £600. Track/slide 19 03.45 The case of Tool metal manufacturing co 1955 shows that Promissory Estoppel is suspensory and can be revoked by giving reasonable notice that the original position is being returned to. We can now move on to the very important case of D & C BUILDERS v REES 1966 This is a very good case for you to read – it is only 9 pages long but makes some very good points. D & C builders were jobbing builders comprising just the two people, one a decorator Mr Donaldson, and the other a plumber, Mr Casey. They carried out work for Mr Rees at his business premises, 218 Brick Lane. The bill came to £482 13s 1d and this was not disputed. The plaintiffs requested payment of the bill for months but nothing was forthcoming. At a time when Mr Rees was ill with the flu, his wife spoke to Mr Casey on the phone and said, ‘My husband will offer you £300 in settlement. That is all you’ll get. It is to be in satisfaction’. D and C talked it over and because their company was in desperate financial straits, they decided to take the £300 but ask for the balance later. Mrs Rees said, ‘No, we will never have enough money to pay the balance. £300 is better than nothing’. They decided to accept the £300 and she said, ‘Would you like the money by cash or by cheque. If cash, you can have it on Monday. If a cheque, you can have it tomorrow (Saturday).’ They decided to accept the cheque and when they gave her a standard receipt for it she insisted that they added the words, ‘in completion of the account’. The question was therefore, whether this cheque for £300 amount to full settlement of the whole debt? D & C sued for the balance of £182 13s 1d. Applying Pinnel’s case 1602 and Foakes v Beer 1884 you would think NOT in which case D & C builders should win. Mr Rees tried to rely on Goddard v O’Brien 1882 because in that case a cheque for £100 was held to discharge a debt for £127 7s because the cheque was seen as a NEGOTIABLE SECURITY and so SOMETHING DIFFERENT to what the creditor was entitled to, that is Cash. Thus, Pinnel’s Case was used to say that the negotiable security (the cheque) was the equivalent of a hawk, robe, or a bird and so amounted to new consideration for a lesser payment. Track/slide 20 04.08 What did the 3 Lord Justices of Appeal think of this? We can consider each of their judgments. 1. Winn LJ His lordship noted that doubt as to the correctness of Goddard v O’Brien had been voiced in the Hirachand Punamchand case in 1911 and said that the court should now decline to follow Goddard v O’Brien. He thus dismissed the appeal applying Pinnel’s case and Foakes v Beer – and so the builders could sue for the whole of the debt – the cheque was just like cash. 2. Lord Denning MR First, his lordship said that there is no difference between paying a lesser sum in cash or paying it by cheque and thus Pinnel’s Case and Foakes v Beer applies to both payment methods, as supported in the case of Cumber v Wane 1721. In which case the builders would win. His lordship then used equitable principles and quoted from Hughes v Metropolitan Railway Co 1877 the passage that states: ‘When a debtor and a creditor enter on a course of negotiation, which leads the debtor to suppose that, on payment of the lesser sum, the creditor will not enforce payment of the balance, and on the faith thereof the debtor pays the lesser sum and the creditor accepts it as satisfaction, then the creditor will not be allowed to enforce payment of the balance when it would be INEQUITABLE to do so’. He then referred to the High Trees case to further support this equitable principle. On this basis, it would appear that the builders would lose. HOWEVER He said that this principle DID NOT APPLY IN THE PRESENT CASE because it only applies WHERE IT WOULD BE INEQUITABLE for the creditor to enforce full payment. He said that it was NOT inequitable for the builders to recover the FULL AMOUNT OF THE DEBT because Mrs Rees had HELD THEM TO RANSOM – she had intimidated them to accept less than was due knowing that their company was in dire financial straits. So the builders could win. 3. Dankwerts LJ His lordship stated: ‘Foakes v Beer, applying the decision in Pinnel’s case, settled definitively the rule of law that payment of a lesser sum than the amount of a debt due cannot be a satisfaction of the debt unless there is some benefit to the creditor added so that there is accord and satisfaction’. He felt that a cheque was basically the same as cash and so it was not extra consideration that could be used to avoid Foakes v Beer. Thus, the builders could sue for the balance due. He did note, that a cheque from a THIRD PARTY for less than the whole bill might be consideration to discharge the whole bill though – thinking along the line of the Hirachand case – to avoid fraud to the 3rd party. Track/slide 21 01.50 We can now look at Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd 1991 Glidewell and Russell LJJ suggested that they would have considered promissory estoppel had it been pleaded. But, counsel for the claimant probably realised that they had a better chance of winning by trying to establish extra consideration in the guise of practical benefit rather than trying to get promissory estoppel recognised as a distinct cause of action in its own right. A different approach was however taken in the next case. In Baird Textile Holdings Ltd v Marks & Spencer plc 2001, Baird was contending that M&S was estopped from not ordering garments from them, that M&S should order garments from them. They failed because: firstly, Promissory estoppel is a shield and not a sword and secondly, that there was no clear unequivocal promise by M&S that they would continue to order garments from Baird. It would thus seem that there is a move to get promissory estoppel established as a separate cause of action. But, if it did become one, would it just be for ‘alteration’ promises or would it replace consideration altogether?