Syntax (Li/LT9)

advertisement

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

SYNTAX (LI/LT9)

Syntactic structure and its representation: Phrase structure – from PS-rules

and Transformations to X-Bar Theory

(Handouts will be available from www.mml.cam.ac.uk/ling/courses/p9_Syntax.htm)

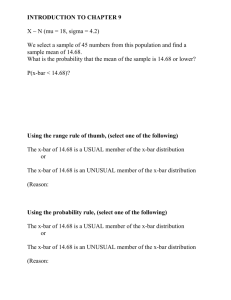

1. Generating syntactic structure (pre-GB)

A. Categories:

lexical: N, V, A(=Adj & Adv), P

functional: Determiner, Auxiliary, Conjunction

B. Constituents

lexical: NP, VP, PP, AP

other: S, S'

how do we get from A to B?

how do A and B – both of which are finite – generate an infinite set of possible

(grammatical) structures? (cf. Wilhelm von Humboldt: “making infinite use of finite

means”)

C. The Lexicon [= our focus next week]

syntactic subcategorization information specified in subcategorization frames

e.g. rely: [V] __ PP

put: [V] __ NP PP

boy: [N] __

in: [P] __ NP

c(ategorial)-selection

semantic subcategorization information specified in selectional rules

e.g. frighten: [V] __ NP

[+animate]

cf. [Syntax] frightens [many students] vs: *[Many students] frighten [syntax]

NP

NP

NP

NP

s(emantic)-selection

D. Phrase Structure

The pre-GB take on how phrase-structure is generated: (PS)-Rules (a.k.a. Rewrite

Rules)

general format for rewrite rules:

A → B (C)

i.e. A rewrites as (i.e. consists of) B (obligatorily) and C (optionally)

(1)

a.

André solved the most recent crisis at the office

PS-rules involved in the generation of (1):

(a)

S → NP VP

[S [NP André] [VP solved the most recent crisis in the office]]

(b)

VP → V NP (PP)

[VP [V solved] [NP the most recent crisis at the office]]

or

1

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

[VP [V solved] [NP the most recent crisis] [PP at the office]]

(a)

Various VP PS-rules

VP → V (AdvP)

e.g. talked (loudly)

VP → V NP (AdvP)

e.g. ate his lunch (eagerly)

VP → V NP PP (AdvP)

e.g. put the book on the table wearily

VP → V NP (PP)

e.g. found the book (on the table)

VP → V S

e.g. know the students attended their lectures

Thus (just combining the rules we’ve considered here):

VP → V (NP) (PP) (AdvP)

S

(c)

NP → (Det) (AP) N (PP)

[NP [D the [AP most recent] [N crisis] [PP at the office]]]

[NP [D the [N office]]]

Various NP PS-rules

NP → N

e.g. books

NP → Adj N

e.g. unopened books

NP → Det Adj N

e.g. the unopened books

NP → Det Adj N PP

e.g. the unopened books on the table

Thus (just combining the rules we have here):

NP → (Det) (Adj) N (PP)

(d)

PP → P (NP)

[PP [P at ] [NP the office]]

Various PP PS-rules

PP → P

e.g. in

PP → P NP

e.g. in my room

PP → AdvP P NP

e.g. right in the corner

Thus:

2

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

PP → (AdvP) P (NP)

(e)

AP → (AP) A (PP)

[AP [AP [A most]] [A recent]]

Various AP PS-rules

AP → A

e.g. happy

AP → Adv A

e.g. ecstatically happy

AP → Adv A PP

e.g. ecstatically happy about the outcome

Thus:

AP → (Adv) A (PP)

Looking ahead to X-Bar Theory: generalisation across lexical constituents

→ an XP minimally consists of an X, i.e. a phrasal category minimally consists of the

head that determines the phrase’s type

or: XP → X (YP), where X = N, V, A, P

What about S, though?

And how do we incorporate the closed class lexical categories (i.e. the functional

categories) into PS-rules?

How do we account for the true recursive property of language that permits infinite

use to be made of finite means?

2. The PS-structure of sentences (S)

How can auxiliaries be incorporated into PS-rules?

cf. interim PS-rule for S ((a) above):

(2)

S → NP VP

(3)

[NP Local people] [VP buy their newspaper at the corner-store]

(4)

Local people might buy their newspaper at the corner-store

(5)

Jonathan will find a surprise at work

(6)

Kristin is reading a book in the library

Evidence that auxiliaries are not part of VP (constituency tests):

(7) Carolyn will [VP buy the rolls] and [VP provide the drinks]

(co-ordination)

[Co-ordination is supposed to conjoin two identical structures, e.g. VP + VP, NP + NP. But this

isn’t always the case – cf. Rob works [AP consistently] and [PP with great energy]; this often

exploited for comic (?) effect – cf. I want the report accurate and within the next hour!]

(8)

Angela will [VPfinish the race in under an hour] and Michael will do so too

(substitution by pro-form; do so = verbal proform)

3

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

(9)

Richard has [VP entered the competition] → I know he has [ ]

(10)

Robert is [VP working on the design]:

What is Robert doing → Working on the design

(elision)

(questioning)

Therefore:

S → NP (Aux) VP [Take I]

Is Aux really optional? What (grammatical) information does it contain?

(11)

a.

b.

Michelle has finished her paper → I know she has [ ]

Richard entered the competition → I know he has/did [ ]

(12)

a.

b.

So her work is finished, is it?

So you read the book yesterday, did you?

(13)

a.

b.

c.

d.

Ich schreibe einen Brief

Du schreibst einen Brief

Andrea schreibt einen Brief

Wir schreiben einen Brief

[German]

versus:

e.

f.

g.

h.

and not:

i.

j.

k.

Ich habe einen Brief geschrieben

Du hast einen Brief geschrieben

Anne hat einen Brief geschrieben

Wir haben einen Brief geschrieben

*Ich habe einen Brief geschriebe

*Du hast einen Brief geschriebst

*Anne hat einen Brief geschriebt

Therefore: Aux is associated with TENSE and AGREEMENT and is obligatorily

present in every sentence, even when it isn’t overtly represented by a distinct element

S → NP Aux VP [Take II]

3. Incorporating conjunctions into PS-rules: the category Comp(lementiser)

(14)

Hugo knew (that) Shelley was wondering whether André secretly drinks gin

(15)

I wonder if you can draw a tree for this sentence?

(16)

I arranged for Poirot to start the investigation.

(17)

I expect () Poirot to abandon the investigation

that, whether and if = subordinating conjunctions in traditional grammar

for = a prepositional conjunction

All are complementizers (Comp/C) in Chomskyan terms

How are complementizers incorporated into PS-Rules?

4

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

2 options suggest themselves:

(18)

S → COMP NP Aux VP

S

COMP NP

Aux

VP

or:

(19)

S’ → COMP S

S’

COMP

S

Evidence that COMPs are not part of

constituents (constituency tests)

S, i.e. that S and COMP are separate

(20)

Sandra knows that Sam understands constituency tests and *(that) he is good at

practical phonetics too

(co-ordination)

(21)

I’ve been wondering whether - but am not entirely sure that - the President will

approve the project (Radford 1988: 293, e.g. 24)

Therefore:

S’ → COMP S

4. PS-rules and Recursion

The (original) generative aim in analysing a given language: to generate all and only

the sentences that are possible in that language

How do we deal with:

(22) I suspect André thinks Hugo knows Jonathan understands …

(23)

This is the farmer sowing the corn, that kept the cock that crowed in the morn,

that waked the priest all shaven and shorn, that married the man all tattered and

torn, that kissed the maiden all forlorn, that milked the cow with the crumpled

horn, that tossed the dog, that worried the cat, that killed the rat, that ate the

malt, that lay in the house that Jack built …

(24)

The big black frightening, shaggy, flee-ridden … dog

(25)

This could go on and on and on and on and on and on and on and on and …

PS-Rules have to allow for recursion

S’ recursion (cf. (22-23)) falls out from the interaction of PS-rules (a) – (c):

(a) S’ → COMP S

(b) S → NP Aux VP

5

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

(c) VP → V S’

[so a “loop” arises for as long as the VP in (b) “decomposes/rewrites” as (c), which

then means (a) has to be implemented again → (b) → (c), etc.]

AP recursion (cf. (24)):

AP → AP (PP) or AP → A* (PP) where * signals recursion rather than

ungrammaticality

Co-ordination recursion (cf. (25)):

“AndP” → “AndP” X

(many aspects of co-ordination remain mysterious in modern syntactic theory …)

[so both the AP and the co-ordination recursion cases feature the same category on

either side of the “rewrite” arrow, indicating that we’re dealing with a category that

“contains” instances of itself, also the three rules (a-c) have S’ on both sides of the

arrow, taken together.]

5. Problems with PS-Rules

they are very directly based on traditional grammar descriptions of the various

constructions that are available in specific languages (“translation” pitfall)

(consequently) they are inevitably both construction- and language-specific

English and Japanese VPs and NPs cannot be derived from the same PS-rules:

English:

(26) a.

b.

Japanese:

(27) a.

b.

VP → V NP: The reporter [VP wrote a terrible story]

PP → P NP, e.g. from South Africa

VP → NP V: Sensei wa [VPTaroo o sikata]

Teacher TOPIC Taro OBJECT scolded

“The teacher scolded Taro”

PP → NP P: Nihon kara

Japan from

“from Japan”

they over-generate: in principle, there is nothing stopping this system from having

constituents generated by rules like: NP → V A and VP → P NP. Observation

shows us that natural language constituents are endocentric (determined by the

nature of a head), but the fact of the matter is that PS-Rules are not restricted to

generating only endocentric constituents.

they under-generate:

they can’t represent the difference between constituents that are closely connected

to one another – e.g. found and the book in Andrew found the book on his bed –

and those which are more loosely/optionally connected – e.g. found and on his bed

in the preceding example

they duplicate subcategorization information in the Lexicon (this will become

clearer next week)

6

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

6.

X-Bar Theory

different division of labour:

A. The GB Lexicon

Idiosyncratic lexical information is stored in the Lexicon and fed through to the Syntax

in accordance with the Projection Principle in (28):

(28)

Lexical (i.e. c-selection) information is syntactically represented

i.e. the information that is specified in the Lexicon determines the way items are slotted

into the phrase structure

B. GB Phrase Structure Theory: X-Bar Theory

central assumption:

category-neutrality: all syntactic categories have the same basic internal structure.

7.1.

Endocentricity

in building up a phrasal constituent, there is always one obligatory constituent, the

head, which determines the nature of the phrasal constituent (=maximal

projection) as a whole, i.e. for all PS-Rules, the following generalisation holds:

XP → … X …

(29)

this immediately eliminates problematic non-occurring potential PS-rules of

the VP → A NP and PP → VA type

7.2. Complement and, Specifiers

PS-Rules can’t distinguish between subcategorized and non-subcategorized

categories of a head (i.e. between those that are actually specified in the lexicon and

those which are added as “optional extras” or, like subjects, once the relationship

between subcategorized elements has been established)

(30)

Liz baked a cake in the microwave

[VP [V baked] [NP [D a] [N cake]] [PP [P in] [NP [D the]] [N microwave]]

VP

V

baked

NP

PP

a cake

in the microwave

o a cake is semantically closely related to the verb, baked; therefore its

subcategorization frame is closely related to that of bake which takes one

complement – i.e. bake – [V] __ NP.

Thus: bake – [V] __ PP

i.e. bake subcategorises for an NP-complement (i.e. “completer”) with which it

forms a particularly close relationship (cf. constituency tests: Liz baked a cake

and Ben did so too, not *Liz baked a cake and Ben did so cookies ← did so

7

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

substitutes for VP, so a cake (and cookies in Liz baked a cake and Ben made

cookies) must be part of VP)

o complements are structurally represented as sisters of X in X-bar theory – cf.

(31):

(31)

XP

ru

X

Complement

Sisterhood represents the closest structural relationship; a complement is the

element most closely related to a head (X).

o some non-subcategorised categories are also relatively more closely connected

to the head than others – cf. Liz above compared to in the microwave in: Lik

baked a cake is fine, but *baked a cake in the microwave is missing something,

namely a specifier (here: a specification of who did the baking)

o specifiers are structurally represented as sisters of X’ in X-bar theory – cf. (32):

(32)

XP

ru

Spec(ifier)

X’ (where X’ reads “X-bar”)

ru

Comp(lement)1

X

o structurally, therefore, a complement = the sister of a head, while a specifier =

the sister of the head + complement structure (X’) → different levels of syntactic

“closeness” are structurally represented

So far: 3-level structure

(a) head (X)

(b) head (X) + its complement = X’

(c) [X’ head (X) + its complement] + specifier = XP

Thus, where complement = YP, the specifier = ZP and commas indicate that relative

ordering is not fixed (i.e. Complements can follow their specifiers [e.g.English] and

precede them in others [e.g. Japanese] – cf. (36) – (37) above):

XP → Spec, X’ / XP → YP, X’

X’ → X, Comp / X’ → X, ZP

Some terminology:

X’ is an intermediate projection between the head (X) and its maximal

projection (XP)

depending on the subcategorization information in the lexicon, Comp may, like

Spec, not be generated (hence the importance of the Projection Principle)

X-Bar Theory is nevertheless meant to operate in a “blind” fashion as far as its

hierarchical structure is concerned: although complements and specifiers are

1

Note that Comp is a homonym in syntactic theory: here it refers to the complement, i.e. a constituent

that a head subcategorises for, whereas it can also refer to a complementizer, i.e. elements like that, if,

for, etc.

8

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

generated depending on lexical considerations, it is always essential that X be

dominated by (at least one – cf. section 7.3 below) X’ and that X’ be dominated

by (at least one) XP – cf. the X-Bar representation of Liz (strictly speaking;

textbooks generally don’t bother to fill in all the redundant structure, but this is

theoretically important):

(33)

NP

N’

N

Liz

7.3.

Adjuncts

some non-subcategorized categories are only loosely and very clearly optionally

connected with the head(-complement) unit

I carefully put Paul’s buttery card into his pigeonhole two hours before lunch on

that rainy day

(35) He cleverly only partially solved the problem

(36) A tall, dark, handsome, Guardian-clutching stranger

(37) He was severely directly personally critical of the President (Radford 1988: 245)

the fact that these optional constituents can be “stacked” suggests that they aren’t

specifiers which, by definition, aren’t “stackable” – cf. *Jonathan’s the solution to

the problem, but Jonathan’s solution to the problem and the solution to the problem

(cf. a tall stranger; a tall, dark stranger; a tall, dark, handsome stranger; etc.)

X-Bar theory allows for a single specifier position

there seem to be many positions available for optional elements (which commonly

feature in recursion structures)

optional elements = adjuncts in X-Bar terms because they are adjoined to a given

projection without altering its nature (regardless of the number of adjectives that

are strung between a and stranger in (36), this constituent will remain an NP; and

we know APs are recursive – cf. the PS-rule associated with (24))

representing adjuncts in X-Bar Theory: adjuncts adjoin to X’ to form a larger X’, i.e.

adjuncts are sisters of X’ and daughters of X’

(34)

(38)

NP

ei

Spec

(=NP)

N’

ep

AP

N’

A’

N’

ei

N

PP

N

Jonathan’s

A

brilliant

solution

to the problem

where triangles are used as shorthand in place of the full articulated X-Bar structure

In X-Bar terms:

X’ → X’ YP

9

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

So this is another recursive rule.

7.4.

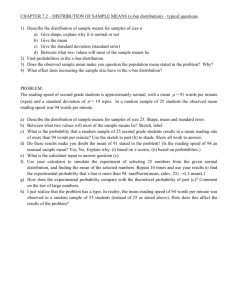

Summary of the X-Bar Schema and their most straightforward implementation

(39)

{XP}

Adjunct

XP

Spec

{X’}

Adjunct

X’

Comp

X

Adjunct

Spec

Adjunct

Comp

(optionally recursive structure indicated in { })

Thus:

X is a variable over categories (X can be N, V, A, P, I, C, etc.)

complements are always closest to the heads that select them

adjuncts are optional elements which can be omitted as they simply “repeat” a level

of structure (X’ or XP)

8.

X-Bar Theory and Lexical Phrases: summary

(see Radford 1988 for a very detailed discussion)

8.1. NPs

Complements are PPs or CPs:

(40) Liz’s solution to the problem

(41) the fact that Week 3 is nigh

Adjuncts are typically APs (e.g. a very long handout!)

Specifiers are typically determiner-type elements (e.g. the/this/Jonathan’s) …

although there’s a complication here … (see Week 5 on the DP Hypothesis)

the X-Bar Schema explain why complements are closer to the heads that select them

than adjuncts

cf. a student of syntax – PP complement

a student with blue eyes – PP adjunct

a student of syntax with blue eyes and not: *a student with blue eyes of syntax

8.2. APs

Complements are PPs

(42) proud of her achievements

Adjuncts are APs (AdvPs)

(43) incredibly proud of her achievements

Specifiers are degree modifiers (i.e. a very restricted subset of the class of APs)

(44) so/as/that extremely proud of her achievements

10

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

8.3. PPs

Complements are NPs and PPs

(45) from the drawer

(46) from under the bed

Adjuncts are APs (AdvPs)

(47) completely in the wrong (these are stackable – cf. completely, utterly, totally

wrong)

Specifiers seem to be rather restricted (mostly APs)

(48) right/just/5 days before the meeting (these aren’t stackable)

8.4. VPs

Complements are PPs or NPs or CPs (cf. subcategorization frame)

Adjuncts are typically PPs or APs (where the A-head is an adverb - cf. late above)

(49) a.

Andy arrived for the meeting late

b.

Andy arrived late for the meeting

(cf. variable ordering between 2 adjuncts which is impossible when we are

dealing with a complement and an adjunct – how does X-Bar Theory predict

this?)

Specifiers? No category immediately suggests itself (but see Week 3)

8. X-Bar Theory and Functional Phrases

9.1. Sentences

Recall PS-rule for sentences: S → NP Aux VP → exocentric

Can S be brought in line with the endocentric X-bar pattern?

various considerations suggesting Aux (!!) should be analysed as the head of S

Aux plays an important role in determining the nature of the sentence in that it

establishes the TENSE of the sentence. In at least one sense, a sentence is a tensed

proposition. In that sense, Aux can be regarded as a head in the same way that N,

V, A and P can – i.e. S can be regarded as fundamentally an AuxP headed by Aux

Therefore:

S → NP Aux VP becomes AuxP → NP Aux VP

In GB literature (following Chomsky 1986), AuxP is referred to as IP (Inflectional

Phrase) with head I(nfl) (=Aux).

Therefore (alternative notation):

AuxP → NP Aux VP becomes IP → NP I VP

IP (=S) → NP I (=Aux) VP (Take III - final)

3 non-optional constituent parts; but the X-Bar Schema generate binary structures

Subject as Specifier:

(50) James regularly walks the Master’s dog

the subject determines (i.e. specifies) what verb-form is appropriate (3ps)

this is even more clearly seen in languages with regular verbal morphology (e.g.

German)

the agreement between the subject and the verb is actually agreement between the

subject and I; therefore it is referred to as Spec-Head Agreement. Spec-Head

Agreement is mandatory – cf. *We smiles and *They sings and *Nicola run

A complication: specifiers are generally optional, but, for English at least, it looks

very much as if the pre-I position always has to be filled:

11

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

(51) a.

A unicorn sleeps in the garden

b.

*sleeps a unicorn in the garden

c.

There sleeps a unicorn in the garden

Spec-IP must be filled, even if only with a “semantically empty” element like

the expletive there, i.e. the filling requirement is a purely formal one.

The principle (i.e. assumed invariant universal) expressing this fact is (69):

(52)

Extended Projection Principle (EPP)

Every clause must have a subject

(Therefore subjects are non-optional specifiers.)

Important distinction:

o The Projection Principle (PP) ensures that all c-selected categories are present

in the syntax (see also Week 3)

o The EXTENDED Projection Principle (EPP) ensures that a subject (i.e. an

element which heads don’t c-select) is present at all times. So the EPP extends

the PP in the sense that it ensures the presence of an additional constituent which

is not specified as necessary by the PP (we’ll come back to this).

IP adjuncts = APs and PPs (i.e. sentence adverbials)

(53) The candidates clearly/undoubtedly/certainly annoy each other

IP complements = VP and IPnon-finite

(54)

(55)

Angela has [VPwatered the garden diligently]

Corpus seems [IP to be on track for victory]

9.2. S’

Recall PS-rule for S’: S’ → Comp S → exocentric

Can S’ be brought in line with the endocentric X-bar pattern?

S is clearly a phrase; therefore Comp is the only possible head – Does it determine

the nature of S’ in any way?

Yes: the nature of S’ as a whole is determined by the complementizer (COMP) that

introduces it.

cf. that → [+declarative; +finite] S’ and S/IP

if and whether → [+interrogative; +finite] S’ and S/IP

for → [+declarative; -finite] S’ and S/IP

Therefore:

CP → C(omp) S/IP

Regarding the X-Bar structure of CP:

Cs take IP complements

(56) I know that André is working hard

(57) I wonder if André is working hard

CP Specifiers?

12

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

o Recall the yes/no transformation which moved auxiliary (I) elements into clauseinitial/pre-subject position – e.g. Are you singing Brahms? from You are singing

Brahms

o Since the EPP forces subjects to be present in all cases and subjects were shown

to be Spec-IP elements, the inverted auxiliary must be in C

CP

ru

Spec

C’

ru

C

IP

arej

ru

Spec

I’

youj

ru

I

VP

tj

ru

Spec

V’

tj

ru

V

NP

singing

Brahms

o Wh-interrogatives: What are you singing? → Spec-CP slot available for

(phrasal) wh-expressions like what (piece of music)

Therefore: wh-expressions are one type of CP-specifier (they specify that the CP in

question is a wh-interrogative

CP adjuncts? Possibly topicalised XPs – e.g. syntax in Syntax, I really like

10.

Remaining problems (respects in which X-Bar Theory appears to be too

restrictive … up for discussion in various future lectures)

X-Bar structures are binary

how are the complements of ditransitive verbs to be represented? [cf. Larson

1988 for a solution, to be discussed next week]

what about the structure of particle verbs – I put the briefcase down where the

briefcase is the complement of an apparently discontinuous verb, put down

and co-ordinating structures – [the student] and [the old lady]

X-Bar structures are crucially headed/endocentric

what about structures that genuinely appear to be headless – e.g. so-called small

clauses: I find [syntax riveting] and The captain expects [the drunken sailors off the

ship] immediately

what about the odd range of specifiers that NPs seem to have? – cf. [the] book vs

[that most eminent great man’s] book → the seems head-like (which shouldn’t be

allowed as specifiers must be phrases/XPs), whereas that most eminent great man’s

is clearly a phrase

what about structures that appear to exhibit a mixture of verbal and nominal

characteristics? – cf. his heartless destruction of the city vs his heartlessly

destroying the city (cf. the DP Hypothesis)

References

1. Lecture 2-related reading

Carnie, A. (2002). Syntax. A Generative Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell. (chapter 2, 3,

5 & 6)

13

Li/LT9 – 20 October 2010

Chametzky, R. (2000). Phrase Structure. From GB to Minimalism. London:

Blackwell. (chapter 1).

Chomsky, N. (1986). Knowledge of Language. Its Nature, Origin and Use. London:

Praeger. (relevant sections; consult index)

Crain, S. & D. Lillo-Martin (1999). An Introduction to Linguistic Theory and Language

Acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell. (Part II)

Culicover, P. (1997). Principles and Parameters. An Introduction to Syntactic Theory.

Oxford: OUP. (chapter 5).

Haegeman, L. (2006). Thinking syntactically: a guide to argumentation and analsyis.

London: Blackwell. (chapter 3)

Haegeman, L. (1995). An Introduction to Government and Binding. London:

Blackwell. (chapters 1 and 2)

Haegeman, L. and J. Guéron (1999). English Grammar. A Generative Perspective.

London: Blackwell. (Part 1: particularly sub-sections 2.3 - 2.5).

Jackendoff, R. (1977). X-Bar Syntax: A Study of Phrase Structure. Cambridge, Ma:

MIT Press.

Koopman, H. and D. Sportiche (1991). The position of subjects. Lingua 85 (special

issue on VSO languages).

Larson, R. (1988). On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 103 - 139.

Larson, R. (1990). Double objects revisited: a reply to Jackendoff. Linguistics Inquiry

21: 589 - 632.

Ouhalla, J. (1994/1999). Introducing Transformational Grammar. London: Arnold.

(chapter 4 and section 6.4 [DP Hypothesis] of the 1994 edition; chapter 6 of Part

II of the 1999 edition).

Poole, G. (2002). Syntactic Theory. London: Palgrave. (chapters 2 & 3)

Radford, A. (1988). Transformational Grammar. A First Course. Cambridge: CUP.

(chapters 4 - 6).

Radford, A. (1997). Syntactic theory and the structure of English. A minimalist

approach. (chapter 9 focuses on vP shells which is a development of Larson’s

original idea).

Roberts, I. (1997). Comparative Syntax. London: Arnold. (relevant bits of chapter 1).

Smith, N. (1999). Chomsky. Ideas and Ideals. Cambridge: CUP. (most of chapter 2).

Speas, M. (1990). Phrase Structure in Natural Language. Dordrecht: Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

2.

Useful Preparation for Lecture 3

Haegeman chapter 1 (yet again!!)

Carnie (2002) chapter 7

Poole (2002) chapter 4

Ouhalla (1994) chapter 5/(1999) chapter 7 of Part II

Radford (1988) chapter 7

14