Airway Assessment and Failed Intubation

advertisement

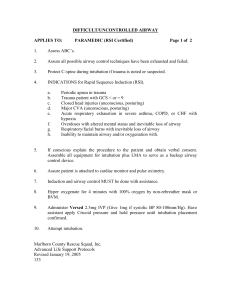

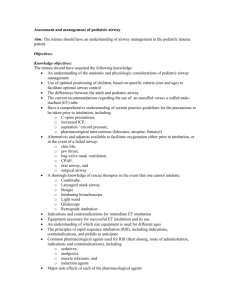

AIRWAY ASSESSMENT AND FAILED INTUBATION “Achilles”, (Brad Pitt, in “Troy”, Warner Bros, 2004) “Gleaming helmets, polished spears, metalled breastplates and ash-wood spears were borne in torrents from the ships. The glitter of these arms illuminated the sky, the glow of bronze rippled like laughter over the plain and the ground shook under the feet of the marching army. Among them the great Achilles took up his arms. In the unbearable fury that gripped him, he ground his teeth, and his eyes blazed with a fire as he donned the divine gifts of Hephaestus. His heart burned with hatred for the Trojans. He first tied around his legs the splendid shin-guards with their silver ankle clips. Next he lifted the cuirass on to his chest, and over his shoulder slung the bronze sword with its studded hilt. Then he took up the massive shield, which flashed into the distance as if it were the moon, or the gleam sailors glimpse at sea from a fire on the uplands as they are taken from home along the highways of the fish by exiling winds. Such was the light that went up into the sky from Achilles’ magnificent shield. Next he took up the mighty helmet and placed it on his head. It scintillated like a star, and the plumes Hephaestus had fashioned for the crest danced in a crescent of gold. Prince Achilles flexed his splendid limbs in the armour to check its fit, and found free movement. It felt as light as a pair of wings lifting him up. Finally he took up his father’s spear from its case, the weighty, long and formidable weapon no Greek could wield but he, who knew its balance. It was made from an ash tree felled on Mount Pelion and had been given by Cherion to his father, Peleus, to bring death to his noble enemies”. Homer, The Illiad 8th Century BCE The ancient Greeks knew they had a very difficult battle on their hands when they decided to attack and gain control over the city of Troy, in fact it would take them no less than 10 years before victory was theirs. After carefully assessing all arguments for and against the attack they decided to go ahead but only after the most meticulous planning and with all the “cutting edge” weaponry and technology of the time at their disposal. When faced with a difficult airway, we must like the ancient Greeks plan our “attack” for control over the airway meticulously. Like Achilles himself who checked for “free movement” so must we check for free movement of our patient’s airway. We must have at our disposal a “glittering” array of equipment should we encounter any difficulties. We must know the “balance” of this equipment and ensure that like the shield of Achilles our laryngoscopes will “flash into the distance” just as the moon. AIRWAY ASSESSMENT AND FAILED INTUBATION Indications for an ETT 1. 2. 3. Relief of airway obstruction, including ● Croup ● Epiglottitis Airway protection: ● Loss of gag reflex, (within clinical context). ● GCS less or equal than 8 (within clinical context). Respiratory / Ventilatory failure: ● Failure to maintain a PaO2 of 60 mmHg, despite a 60 % (or more) concentration of inspired oxygen, (within clinical context). ● A rising PaCO2, (within clinical context). ● Physical exhaustion. 4. A confused and uncooperative patient who requires urgent investigation and / or management for a life threatening condition. 5. Any unfasted patient that requires general anaesthesia (within clinical context). 6. Prophylactic management, including: ● Inevitable or highly likely airway obstruction, such as severe neck and facial burns. ● Inevitable or highly likely respiratory failure, such as large traumatic flail segments or significantly ruptured diaphragm. Airway Assessment Evaluating the potential for a difficult intubation includes: 1. General Inspection: ● Short stocky, (“bull neck”) ● Receding mandible, (micrognathia) ● Prominent incisors. 2. 3. ● Large tongue, (macroglossia) ● High arched palate Mobility assessments ● Cervical spine. ● TMJ a. Mouth opening, (at least 2 finger breadths) b. Protraction / Retraction. Measurements ● Mallampati Score This classification is based on the finding that visualization of the glottis is impaired when the base of the tongue is disproportionately large. The assessment is made with the patient sitting upright, head in neutral position, mouth open as wide as possible and the tongue protruded maximally. Class I Soft palate and uvula (and faucial pillars) are clearly visible with the soft palate away from the tongue. Class II The soft palate and only part of the uvula can be seen. Class III Only the soft palate is visible. Class IV The soft palate is not visible, (only the hard palate). Class III and IV are likely to present intubation difficulties. ● Thyro-mental distance This is measured from the lower border of the mandible to the top of the thyroid cartilage notch with the neck fully extended. a. About 4 finger breadths. b. Greater than 7 cm, (adults) If less than these measures there may be difficulty in visualizing the glottis. 4. A past history of difficult intubation. The patient history should be consulted. One objective measure of the degree of difficulty is the Cormack – Lehane score, which records the ease with which the cords and epiglottis can be visualized. Cormack and Lehane Grade: 5. Grade I Complete glottis visible. Grade II Anterior glottis not seen. Grade III Epiglottis seen, but not glottis. Grade IV Epiglottis not seen. Local pathology such as trauma or peri-tonsillar abscess. Failed Intubation It is critical to have ready extra and spare equipment in the event that intubation proves difficult / impossible. A range of ETT sizes, bougie, introducers, suction, and a second (tested) laryngoscope should all be on hand. FAILED INTUBATION Can effectively ventilate Cannot effectively ventilate Bag Valve Mask & Optimise airway manoeuvres (see below) Laryngeal mask with cricoid pressure. Cords visible Placement of size 6 ETT through laryngeal mask. Yes No Introducer or difficult intubation equipment. Gum elastic Bougie Optimising airway view: Measures include, (non trauma): 1. Jaw lift. 2. Neck extension. 3. Additional pillow. 4. Oral airway to assist effective bag valve masking. 5. Laryngeal manoeuvres: ● Cricoid pressure, (may need more or less) ● “BURP” Still unable to effectively Ventilate. Surgical airway. This manoeuvre involves an attempt to bring the larynx into better view, by pressing backwards, upward, to the right pressure. References Mallampati SR, et al, “A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study”, Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985 Jul; 32(4): 429-34. Dr J. Hayes May 2005