Reading for Results – 11th Edition

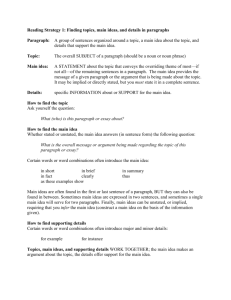

advertisement

Part II: Reading Tips from Chapters 1-11 1 Reading for Results – 11th edition Reading Tips Chapter 1: Strategies for Textbook Learning Be a flexible reader who consciously adapts your reading strategies to the text in front of you. If, for instance, reading your history text at the same pace you were reading your health text leaves you confused, be ready to adapt to the more difficult material by slowing down your reading rate. Serious learners use trial and error to figure out what works for them and for the material they want to master. When one strategy doesn’t work, they try another. Using a variety of page-marking techniques will keep you focused and sharp. It will also help your remember what you read. Chapter 2: Building Word Power If you are an ESL student, pronunciation of new words is especially important to you. Anytime you can get access to an online dictionary, you should use it. Hit the audio link () that will allow you to hear the words pronounced, over and over again if need be. Next time you turn to a dictionary to look up an unfamiliar word, and find several definitions, quickly eliminate any meanings that have no bearing on the word’s context. Then look for the meaning that makes the most sense within the original sentence or passage. † Chapter 3: Connecting the General to the Specific in Reading and Writing As soon as you spot a general sentence, check to see how the sentences that follow clarify or explain it.† If the second sentence in a paragraph explains the first, the chances are good that the opening general sentence expresses the main idea. Chapter 4: From Topics to Topic Sentences If a text is particularly difficult to read, pronouns are often the source of the confusion. If you are struggling with a passage, re-read it to nail down the antecedent, or reference, for every pronoun. † † For more on dictionary labels that will help you in the process of elimination, see pages 000-000 of the Appendix. This advice will become crucial in Chapter 4, when you look for the main idea or message of a paragraph. To test whether a sentence is a topic sentence, turn it into a question. If the remaining sentences answer the question, you’ve found the topic sentence. When taking notes, think of the main idea as the headline you would write if the paragraph were a newspaper article, e.g., “Citizens Blow Off Jury Duty” or “Excessive Self-esteem More Common than Low.” If the second sentence of a paragraph functions as a transition, then the third sentence is likely to be the topic sentence. If a paragraph maintains a consistent level of specific detail and suddenly branches out into the general statement at the end, that last sentence is probably the topic sentence. If a paragraph opens with a general statement, becomes more specific, and then turns more general again at the end, check to see if the opening and closing sentences say much the same thing. If they do, you are reading a paragraph with a double topic sentence. Chapter 5: Focusing on Supporting Details Once you think you have identified the topic sentence, ask yourself which of the remaining sentences provide clarification or evidence for that sentence. If the remaining sentences don’t do either, you need to rethink your choice of topic sentences. If you eliminate a minor detail from a paragraph, the main idea expressed by the topic sentence should remain clear and convincing. If it doesn’t, the detail you eliminated is probably more major than minor. Evaluate minor details very carefully. If the minor details are essential to explaining a major detail, they belong in your notes. To decide what major or minor details are essential to the main idea, ask yourself, How would I explain the content of this paragraph to someone who has never read it? The answer to that question will also identify essential details. Never assume the writers provide you with every single word or phrase you need to construct their intended meaning. Be ready to fill in the gaps with the right inferences. Chapter 6: More About Inferences Inferring implied main ideas is a two-step process. First, you need to understand what each sentence contributes to your knowledge of the topic. Next, you need to ask yourself what all the sentences combine to imply as a group. The answer to that question is the implied main idea of the paragraph. The main idea you infer from the specific details should sum up the paragraph in the same way a topic sentence does. When a writer describes an event or experience by piling up specific details without including a topic sentence that interprets or evaluates them, you need to infer the main idea implied by the author. When the opening question of a paragraph is not followed by an immediate answer, it’s usually the reader’s job to infer an answer that is also the implied main idea. When the author offers several competing points of view without evaluating them, you need to infer a main idea that expresses the variety of opinions concerning the issue, or event under discussion. If a paragraph lists similarities and differences between two topics but doesn’t tell you what those similarities and differences mean or how to evaluate them, you need to infer a main idea which makes a general point that can include all or most of them. If the author cites research but doesn’t interpret the results, you need to infer what the research results suggest about the problem or issue under study. Chapter 7: Drawing Inferences from Visual Aids Look at pie charts both before and after reading. Look the first time to make predictions about the reading, the second to make sure you understand what the pie chart adds to the author’s point. Chapter 8: Beyond the Paragraph: Reading Longer Selections When you spot a concluding paragraph in a chapter section, check to see if it contains a prediction, consequence, or solution you should record in your notes. If the paragraph functions as a transition, use that information to make some predictions about what the upcoming chapter section will accomplish. As soon as you see a title or heading, consider what it reveals about the material. Some titles do not reveal main ideas or the author’s purpose—for example, “Shadow Juries.”† Others all but announce both—for example, “We Need to Question the Ethics of Shadow Juries.” If the author maintains a formal, impersonal style and does not offer a judgment or call for change, the primary purpose is probably informative, rather than persuasive. Look at the beginning of paragraphs for the answer to two questions that should always be on a reader’s mind: Why does this paragraph follow the previous one? What connects them to one another? Any time you read descriptions of physical characteristics or chains of events, try to visualize the characteristics, the events or both while you read. Chapter 9: Recognizing Patterns of Organization in Paragraphs In the listing pattern, it’s unlikely that the topic sentence would be in the middle of the paragraph. In this pattern, the topic sentence appears at the very beginning or the very end. Make sure you know what main idea is developed by the description of differences and similarities. Chapter 10: Combining Patterns in Paragraphs and Longer Readings In a reading that combines several patterns, one pattern might well dominate, or be primary, but you still need to find and evaluate the key elements in the less important patterns. Then you can decide which of those elements are important enough to appear in your notes. Chapter 11: More on Purpose, Tone, and Bias Sometimes what writers leave out of an explanation is as important as what they put in. Any time a writer decides to do your thinking for you by saying that a particular point of view is “undeniable” or evidence is “overwhelming,” it probably means that the person writing hasn’t built a convincing case. † Shadow juries mimic real juries as closely as possible. Lawyers assemble shadow juries to decide how jury verdicts might turn out.