Ice Inquiry – briefing notes - ACT Council of Social Service

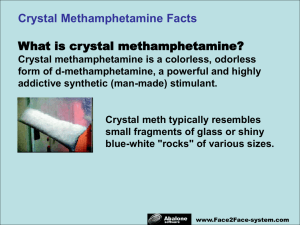

advertisement