RESOLUTTION of APPRECIATION Presented to James ADOMANIS

advertisement

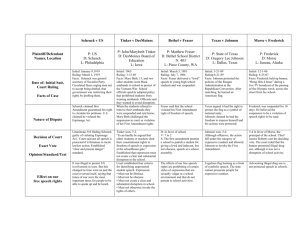

SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 Wynar v. Douglas County School District No. 11-17127 (9th Cir. August 29, 2013) Cases Relied Upon Q: Under what circumstances, if any, are school officials permitted to discipline students for off-campus speech? Counsel for both sides relied on the following cases (excerpted below): Tinker v. Des Moines, 393 U.S. 503 (1969) First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate. This has been the unmistakable holding of this Court for almost 50 years. In Meyer v. Nebraska (1923), and Bartels v. Iowa (1923), this Court, in opinions by Mr. Justice McReynolds, held that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prevents States from forbidding the teaching of a foreign language to young students. Statutes to this effect, the Court held, unconstitutionally interfere with the liberty of teacher, student, and parent. See also Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925); West Virginia v. Barnette; McCollum v. Board of Education (1948); Wieman v. Updegraff (1952) (concurring opinion); Sweezy v. New Hampshire (1957); Shelton v. Tucker (1960); Engel v. Vitale (1962); Keyishian v. Board of Regents (1967); Epperson v. Arkansas (1968). In West Virginia v. Barnette, this Court held that, under the First Amendment, the student in public school may not be compelled to salute the flag. Speaking through Mr. Justice Jackson, the Court said: The Fourteenth Amendment, as now applied to the States, protects the citizen against the State itself and all of its creatures -- Boards of Education not excepted. These have, of course, important, delicate, and highly discretionary functions, but none that they may not perform within the limits of the Bill of Rights. That they are educating the young for citizenship is reason for scrupulous protection of Constitutional freedoms of the individual, if we are not to strangle the free mind at its source and teach youth to discount important principles of our government as mere platitudes. On the other hand, the Court has repeatedly emphasized the need for affirming the comprehensive authority of the States and of school officials, consistent with fundamental constitutional safeguards, to prescribe and control conduct in the schools. See Epperson v. Arkansas; Meyer v. Nebraska. Our problem lies in the area where students in the exercise of First Amendment rights collide with the rules of the school authorities. ..... 1 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 In order for the State in the person of school officials to justify prohibition of a particular expression of opinion, it must be able to show that its action was caused by something more than a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint. Certainly where there is no finding and no showing that engaging in the forbidden conduct would "materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school," the prohibition cannot be sustained. Burnside v. Byars. In the present case, the District Court made no such finding, and our independent examination of the record fails to yield evidence that the school authorities had reason to anticipate that the wearing of the armbands would substantially interfere with the work of the school or impinge upon the rights of other students. Even an official memorandum prepared after the suspension that listed the reasons for the ban on wearing the armbands made no reference to the anticipation of such disruption. On the contrary, the action of the school authorities appears to have been based upon an urgent wish to avoid the controversy which might result from the expression, even by the silent symbol of armbands, of opposition to this Nation's part in the conflagration in Vietnam. It is revealing, in this respect, that the meeting at which the school principals decided to issue the contested regulation was called in response to a student's statement to the journalism teacher in one of the schools that he wanted to write an article on Vietnam and have it published in the school paper. It is also relevant that the school authorities did not purport to prohibit the wearing of all symbols of political or controversial significance. The record shows that students in some of the schools wore buttons relating to national political campaigns, and some even wore the Iron Cross, traditionally a symbol of Nazism. The order prohibiting the wearing of armbands did not extend to these. Instead, a particular symbol -- black armbands worn to exhibit opposition to this Nation's involvement in Vietnam -- was singled out for prohibition. Clearly, the prohibition of expression of one particular opinion, at least without evidence that it is necessary to avoid material and substantial interference with schoolwork or discipline, is not constitutionally permissible. In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school, as well as out of school, are "persons" under our Constitution. They are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State. In our system, students may not be regarded as closed-circuit recipients of only that which the State chooses to communicate. They may not be confined to the expression of those sentiments that are officially approved. In the absence of a specific showing of constitutionally valid reasons to regulate their speech, students are entitled to freedom of expression of their views. As Judge Gewin, speaking for the Fifth Circuit, said, school 2 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 officials cannot suppress "expressions of feelings with which they do not wish to contend." Burnside v. Byars. In Meyer v. Nebraska, Mr. Justice McReynolds expressed this Nation's repudiation of the principle that a State might so conduct its schools as to "foster a homogeneous people." He said: In order to submerge the individual and develop ideal citizens, Sparta assembled the males at seven into barracks and intrusted their subsequent education and training to official guardians. Although such measures have been deliberately approved by men of great genius, their ideas touching the relation between individual and State were wholly different from those upon which our institutions rest; and it hardly will be affirmed that any legislature could impose such restrictions upon the people of a State without doing violence to both letter and spirit of the Constitution. This principle has been repeated by this Court on numerous occasions during the intervening years. In Keyishian v. Board of Regents, MR. JUSTICE BRENNAN, speaking for the Court, said: The vigilant protection of constitutional freedoms is nowhere more vital than in the community of American schools." Shelton v. Tucker. The classroom is peculiarly the "marketplace of ideas." The Nation's future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth "out of a multitude of tongues, [rather] than through any kind of authoritative selection. The principle of these cases is not confined to the supervised and ordained discussion which takes place in the classroom. The principal use to which the schools are dedicated is to accommodate students during prescribed hours for the purpose of certain types of activities. Among those activities is personal intercommunication among the students. This is not only an inevitable part of the process of attending school; it is also an important part of the educational process. A student's rights, therefore, do not embrace merely the classroom hours. When he is in the cafeteria, or on the playing field, or on the campus during the authorized hours, he may express his opinions, even on controversial subjects like the conflict in Vietnam, if he does so without "materially and substantially interfer[ing] with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school" and without colliding with the rights of others. Burnside v. Byars. But conduct by the student, in class or out of it, which for any reason -- whether it stems from time, place, or type of behavior -materially disrupts classwork or involves substantial disorder or invasion of the rights of others is, of course, not immunized by the constitutional guarantee of freedom of speech. Cf. Blackwell v. Issaquena County Board of Education., 363 F.2d 740 (C.A. 5th Cir.1966). Under our Constitution, free speech is not a right that is given only to be so circumscribed that it exists in principle, but not in fact. Freedom of expression would not truly exist if the right could be exercised only in an area that a benevolent government has provided as a safe haven for crackpots. The Constitution says that Congress (and the States) may not 3 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 abridge the right to free speech. This provision means what it says. We properly read it to permit reasonable regulation of speech-connected activities in carefully restricted circumstances. But we do not confine the permissible exercise of First Amendment rights to a telephone booth or the four corners of a pamphlet, or to supervised and ordained discussion in a school classroom. If a regulation were adopted by school officials forbidding discussion of the Vietnam conflict, or the expression by any student of opposition to it anywhere on school property except as part of a prescribed classroom exercise, it would be obvious that the regulation would violate the constitutional rights of students, at least if it could not be justified by a showing that the students' activities would materially and substantially disrupt the work and discipline of the school. Cf. Hammond [p514] v. South Carolina State College, 272 F.Supp. 947 (D.C.S.C.1967) (orderly protest meeting on state college campus); Dickey v. Alabama State Board of Education, 273 F.Supp. 613 (D.C.M.D. Ala. 967) (expulsion of student editor of college newspaper). In the circumstances of the present case, the prohibition of the silent, passive "witness of the armbands," as one of the children called it, is no less offensive to the Constitution's guarantees. As we have discussed, the record does not demonstrate any facts which might reasonably have led school authorities to forecast substantial disruption of or material interference with school activities, and no disturbances or disorders on the school premises in fact occurred. These petitioners merely went about their ordained rounds in school. Their deviation consisted only in wearing on their sleeve a band of black cloth, not more than two inches wide. They wore it to exhibit their disapproval of the Vietnam hostilities and their advocacy of a truce, to make their views known, and, by their example, to influence others to adopt them. They neither interrupted school activities nor sought to intrude in the school affairs or the lives of others. They caused discussion outside of the classrooms, but no interference with work and no disorder. In the circumstances, our Constitution does not permit officials of the State to deny their form of expression. T.V. ex rel B.V. v. Smith-Green Community School Corporation, 807 F. Supp 2d 767 (N.D. Ind. 2011) . . . Here’s what the record reveals: during the summer of 2009, T.V. and M.K. were both entering the 10th grade at Churubusco High School, a public high school of approximately 400 students. Both T.V. and M.K. were members of the high school’s volleyball team, an extracurricular activity, and M.K. was also a member of the cheerleading squad, also an extracurricular activity, as well as the show choir, which is a cocurricular activity. Cocurricular activities provide for academic credit but also involve activities that take place outside the normal school day. . . . A couple of weeks prior to the tryouts, T.V., M.K. and a number of their friends had 4 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 sleepovers at M.K.’s house. Prior to the first sleepover, the girls bought phallic-shaped rainbow colored lollipops. During the first sleepover, the girls took a number of photographs of themselves sucking on the lollipops. In one, three girls are pictured and M.K. added the caption “Wanna suck on my cock.” In another photograph, a fully-clothed M.K. is sucking on one lollipop while another lollipop is positioned between her legs and a fully-clothed T.V. is pretending to suck on it. During another sleepover, T.V. took a picture of M.K. and another girl pretending to kiss each other. At a final slumber party, more pictures were taken with M.K. wearing lingerie and the other girls in pajamas. One of these pictures shows M.K. standing talking on the phone while another girl holds one of her legs up in the air, with T.V. holding a toy trident as if protruding from her crotch and pointing between M.K.’s legs. In another, T.V. is shown bent over with M.K. poking the trident between her buttocks. A third picture shows T.V. positioned behind another kneeling girl as if engaging in anal sex. In another picture, M.K. poses with money stuck into her lingerie – stripper-style. T.V. posted most of the pictures on her MySpace or Facebook accounts, where they were accessible to persons she had granted “Friend” status. Some of the photos involving the lollipops were also posted on Photo Bucket, where a password is necessary for viewing. None of the images identify the girls as students at Churubusco High School. Neither T.V. nor M.K. ever brought the images to school either in digital or any other format. In their depositions, both T.V. and M.K. characterized what they did as “just joking around” and disclaimed that the images conveyed any scientific, literary or artistic value or message, but testified that the photos were taken and were shared on the internet because the girls thought what they had done was funny and “wanted to share with [their] friends how funny it was.” . . . [Both girls subsequently were suspended from participating in extra-curricular and cocurricular activities for the behavior and postings.] With all respect to the important and valuable function of public school authorities, and the considerable deference to their judgment that is so often due, “[i]t would be an unseemly and dangerous precedent to allow the state, in the guise of school authorities, to reach into a child’s home and control his/her actions there to the same extent that it can control that child when he/she participates in school sponsored activities.” Layshock v. Hermitage School District, F.3d , 2011 WL 2305970, *9 (3rd Cir. June 13, 2011). J.S. v. Blue Mountain School District, No. 08-4138 (3d Cir. June 13, 2011) (M.D. Pa. 2011) This case arose when the School District suspended J.S. for creating, on a weekend and on her home computer, a MySpace profile (the “profile”) making fun of her middle school principal, James McGonigle. The profile contained adult language and sexually explicit 5 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 content. J.S. and her parents sued the School District under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and state law, alleging that the suspension violated J.S.’s First Amendment free speech rights. . . The profile did not identify McGonigle by name, school, or location, though it did contain his official photograph from the School District’s website. The profile was presented as a self- portrayal of a bisexual Alabama middle school principal named “M-Hoe.” The profile contained crude content and vulgar language, ranging from nonsense and juvenile humor to profanity and shameful personal attacks aimed at the principal and his family. For instance, the profile lists M-Hoe’s general interests as: “detention, being a tight ass, riding the fraintrain, spending time with my child (who looks like a gorilla), baseball, my golden pen, fucking in my office, hitting on students and their parents.” In addition, the profile stated in the “About me” section: HELLO CHILDREN[.] yes. it’s your oh so wonderful, hairy, expressionless, sex addict, fagass, put on this world with a small dick PRINCIPAL[.] I have come to myspace so i can pervert the minds of other principal’s [sic] to be just like me. I know, I know, you’re all thrilled[.] Another reason I came to myspace is because - I am keeping an eye on you students (who[m] I care for so much)[.] For those who want to be my friend, and aren’t in my school[,] I love children, sex (any kind), dogs, long walks on the beach, tv, being a dick head, and last but not least my darling wife who looks like a man (who satisfies my needs ) MY FRAINTRAIN. . . . Though disturbing, the record indicates that the profile was so outrageous that no one took its content seriously. J.S. testified that she intended the profile to be a joke between herself and her friends. At her deposition, she testified that she created the profile because she thought it was “comical” insofar as it was so “outrageous.” . . . The School District asserted that the profile disrupted school in the following ways. There were general “rumblings” in the school regarding the profile. More specifically, on Tuesday, March 20, McGonigle was approached by two teachers who informed him that students were discussing the profile in class. Randy Nunemacher, a Middle School math teacher, experienced a disruption in his class when six or seven students were talking and discussing the profile; Nunemacher had to tell the students to stop talking three times, and raised his voice on the third occasion. The exchange lasted about five or six minutes. Nunemacher also testified that he heard two students talking about the profile in his class on another day, but they stopped when he told them to get back to work. Nunemacher admitted that the talking in class was not a unique incident and that he had to tell his students to stop talking about various topics about once a week. Another teacher, Angela Werner, testified that she was approached by a group of eighth grade girls at the end of her Skills for Adolescents course to report the profile. Werner said this did not disrupt her class because the girls spoke with her during the portion of the class when students were 6 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 permitted to work independently. The School District also alleged disruption to Counselor Frain’s job activities. Frain canceled a small number of student counseling appointments to supervise student testing on the morning that McGonigle met with J.S., K.L., and their parents. Counselor Guers was originally scheduled to supervise the student testing, but was asked by McGonigle to sit in on the meetings, so Frain filled in for Guers. This substitution lasted about twenty-five to thirty minutes. There is no evidence that Frain was unable to reschedule the canceled student appointments, and the students who were to meet with her remained in their regular classes. . . . The Supreme Court established a basic framework for assessing student free speech claims in Tinker, and we will assume, without deciding, that Tinker applies to J.S.’s speech in this case. The Court in Tinker held that “to justify prohibition of a particular expression of opinion,” school officials must demonstrate that “the forbidden conduct would materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school.” Tinker. This burden cannot be met if school officials are driven by “a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint.” Moreover, “Tinker requires a specific and significant fear of disruption, not just some remote apprehension of disturbance.” Saxe v. State Coll. Area Sch. Dist., 240 F.3d 200, 211 (3d Cir. 2001). Although Tinker dealt with political speech, the opinion has never been confined to such speech. . . . As this Court has emphasized, with then-Judge Alito writing for the majority, Tinker sets the general rule for regulating school speech, and that rule is subject to several narrow exceptions. Saxe (“Since Tinker, the Supreme Court has carved out a number of narrow categories of speech that a school may restrict even without the threat of substantial disruption.”). The first exception is set out in Fraser, which we interpreted to permit school officials to regulate “‘lewd,’ ‘vulgar,’ ‘indecent,’ and ‘plainly offensive’ speech in school.” (quoting Fraser.) The second exception to Tinker is articulated in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, which allows school officials to “regulate school-sponsored speech (that is, speech that a reasonable observer would view as the school’s own speech) on the basis of any legitimate pedagogical concern.” Saxe. The Supreme Court recently articulated a third exception to Tinker’s general rule in Morse. Although, prior to this case, we have not had an opportunity to analyze the scope of the Morse exception, the Supreme Court itself emphasized the narrow reach of its decision. In Morse, a school punished a student for unfurling, at a school-sponsored event, a large banner containing a message that could reasonably be interpreted as promoting illegal 7 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org SUMMER INSTITUTE June 24-26, 2014 drug use. The Court emphasized that Morse was a school speech case, because “[t]he event occurred during normal school hours,” was sanctioned by the school “as an approved social event or class trip,” was supervised by teachers and administrators from the school, and involved performances by the school band and cheerleaders. The Court then held that “[t]he ‘special characteristics of the school environment,’ and the governmental interest in stopping student drug abuse . . . allow schools to restrict student expression that they reasonably regard as promoting illegal drug use.” Notably, Justice Alito’s concurrence in Morse further emphasizes the narrowness of the Court’s holding, stressing that Morse “stand[s] at the far reaches of what the First Amendment permits.” In fact, Justice Alito only joined the Court’s opinion “on the understanding that the opinion does not hold that the special characteristics of the public schools necessarily justify any other speech restrictions” than those recognized by the Court in Tinker, Fraser, Kuhlmeier, and Morse. Justice Alito also noted that the Morse decision “does not endorse the broad argument . . . that the First Amendment permits public school officials to censor any student speech that interferes with a school’s ‘educational mission.’ This argument can easily be manipulated in dangerous ways, and I would reject it before such abuse occurs.” Moreover, Justice Alito engaged in a detailed discussion distinguishing the role of school authorities from the role of parents, and the school context from the “[o]utside of school” context. There is no dispute that J.S.’s speech did not cause a substantial disruption in the school. The School District’s counsel conceded this point at oral argument and the District Court explicitly found that “a substantial disruption so as to fall under Tinker did not occur.” Nonetheless, the School District now argues that it was justified in punishing J.S. under Tinker because of “facts which might reasonably have led school authorities to forecast substantial disruption of or material interference with school activities . . . .” Tinker. Although the burden is on school authorities to meet Tinker’s requirements to abridge student First Amendment rights, the School District need not prove with absolute certainty that substantial disruption will occur. Doninger v. Niehoff, 527 F.3d 41, 51 (2d Cir. 2008) (holding that Tinker does not require “actual disruption to justify a restraint on student speech”); Lowery v. Euverard, 497 F.3d 584, 591-92 (6th Cir. 2007) (“Tinker does not require school officials to wait until the horse has left the barn before closing the door. . . . [It] does not require certainty, only that the forecast of substantial disruption be reasonable.”); LaVine v. Blaine Sch. Dist., 257 F.3d 981, 989 (9th Cir. 2001) (“Tinker does not require school officials to wait until disruption actually occurs before they may act.”). The facts in this case do not support the conclusion that a forecast of substantial disruption was reasonable. ~These materials were prepared by Hon. Sue Leeson for Classroom Law Project’s use.~ 8 CLASSROOM LAW PROJECT 620 SW Main, Ste. 102, Portland, OR 97205 503-224-4424 www.classroomlaw.org