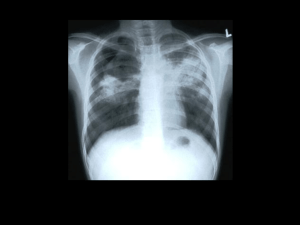

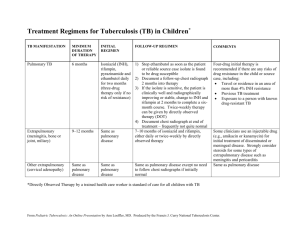

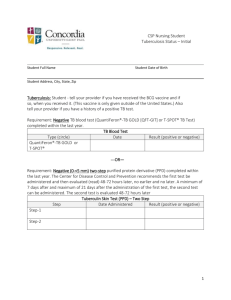

Treatment of Tuberculosis Disease

advertisement