Asist. univ. drd. Simona REDEŞ

advertisement

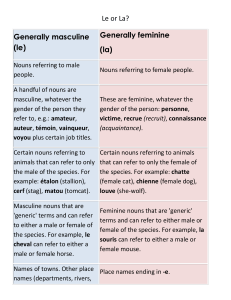

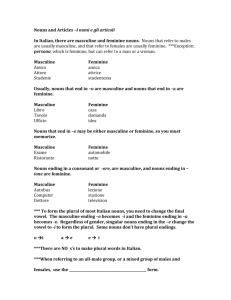

Gender in Romanian and in English, a Brief Contrastive Approach Asist. univ. drd. Simona REDEŞ Universitatea „Aurel Vlaicu” din Arad The paper tries to be a brief comparative approach of the gender mark for the nouns in English and in Romanian. As we all know, the grammatical category of gender is a fundamental one for the nominal flexion in Romanian while in English it is not of great importance. In both languages there are three classes of nouns divided according to gender: masculine, feminine and neuter nouns. The class of masculine nouns includes animates of male sex (both in Romanian and English) and names of objects, inanimates, which according to tradition or through a logical analogy are considered to be masculine (only in Romanian). The class of feminine nouns includes names of being and animals of female sex (in both languages) and names of objects, inanimates, which according to tradition or through a logical analogy are considered to be feminine (only in Romanian). The class of neuter nouns includes nouns that denote inanimates (in English and in Romanian) and nouns having a generic or collective meaning referring to beings. The nouns denoting beings and animals mark the opposition masculine- feminine in the following ways: using different words for masculine and feminine or using suffixes, procedure known as motion. The nouns that mark their gender using the above mentioned ways are included in the class of mobile nouns while those which keep the same form are known as epicenes. They show that even talking about beings sometimes there are situations when there is no connection between the natural sex and the grammatical gender. Another aspect presented in the paper is the common gender, a generic value of a certain number of nouns, denomination that does not take into account the actual difference among the members of that notional aria, but this notion seen as a whole. In order to establish the gender of noun we have to have in mind its desinence, the linguistic context and its determiners (articles, pronouns, adjectives). This paper is not intended to be an exhaustive analysis of this matter, the gender mark of English and Romanian nouns, but the basis of our future research paper. 1. Introduction The components of gender, like those of any other grammatical category, are relevant only in comparison with their opposition. In some languages (like Italian, French or Spanish for example) we can distinguish two components: masculine and feminine. In other languages, though, (English, German or Romanian) there is a third component, the neuter, or there are more than two other components. The classical definitions of gender refer to elements of content. For example, the Romanian grammarian Iorgu Iordan 1 defines gender as” a grammatical category which corresponds, in the case of nouns, to a logical category of their content. Objects are, according to 1 I. Iordan, Limba română contemporană, p. 272 277 their nature, either masculine or feminine, or of no sex”. As a consequence, the traditional denominations given to the three genders in the indo-European languages reflect the obvious connection settled between sex and grammatical gender. But, the modern definitions take more into account the expression and the syntactical implications of gender existence to nouns and to nominal determiners. Jean Dubois 2 defines gender as being a grammatical category based on nouns distribution into nominal classes according to certain formal features, which become obvious through pronominal reference, through adjectival or verbal agreement and at last but not at least through nominal affixes (prefixes, suffixes, case desinences). The Romanian linguistics considers that the gender oppositions are the linguistic equivalents of the oppositions from the extra-linguistic realities. The content of the Romanian nouns gender is made of the opposition between masculine and feminine, components of the animate, on one side, (elev/ elevă) and between these and neuter, the representative of the inanimate, on the other side (elev/ elevă/ curs). As far as the hierarchy of gender oppositions and the opposition that originated this hierarchy is concerned, there are several points of view, some linguists draw a special attention to the opposition animate/ inanimate while others are in favour of masculine/ feminine opposition. Other linguists suggested the use of the term “ambiguous” instead of “neuter”. However, the term “ambiguous” could not replace “neuter” 3 as the Romanian neuter nouns keep and develop the class of neuter nouns (inanimate) from Latin but also because the neuter nouns are a different component of gender than the other two and they are in opposition with the other two components (animate/ inanimate). The Romanian linguists found various procedures of recognition of the noun gender, starting from the feature of the Romanian neuter nouns to have a masculine determiner for singular and a feminine one for plural. This procedure used consists of attaching a determiner to each noun (demonstrative adjective or numeral) and the form of the determiner corresponds to a member of the masculine-feminine pair. Unfortunately, in English we cannot apply the method of gender determination presented above due to the invariable character of most of the parts of speech. Leon Levitchi states in his book “Gramatica limbii engleze” 4 that there are four genders in contemporary English, and these are: -masculine gender for masculine beings: boy, father, elephant -feminine gender for feminine beings: girl, woman, she-wolf -neuter gender for objects, for everything that is inanimate and does not imply the idea of sex: world, peace, house -common gender for both sexes: parent, child, teacher. The common gender has the particularity of characterizing the nouns only when they are seen out of a certain context, because when being in any context, they become always masculine or feminine. The teacher gave a few more examples, as she wanted us to understand the rule. In this sentence, the noun “teacher” is feminine as it results from the use of the personal pronoun “she” which appears in the second sentence. In spite of the fact that the grammatical form of the word does not contain any element that could help us to determine the gender of the noun, there are some lexical means, which make the gender of the English nouns explicit. Gender is not only a simple reflection of reality, but it is rather a matter of convenience and of choice made by the speaker who can use special strategies in order to avoid any reference specific for each gender. 2 J. Dubois, Dictionnaire de linguistique et des sciences du langage, p.217 S. Puşcariu, Limba română, p.131 4 L. Levitchi, Gramatica limbii engleze, p.40 3 278 As we have mentioned the lexical means used for expressing gender, let’s see which they are. One of the most common means used by any speaker of English is the choice of one of the words forming a lexical pair, the choice of the word that denotes the appropriate gender according to what he/ she wants to express. Such lexical pairs can be found in among the vocabulary related to family relationships (father-mother, uncle- aunt, son- daughter), social relationships (king- queen, lord- lady) or names of animals (bull- cow, cock- hen). This distinction between masculine and feminine can be also made using formal marks that are to be extensively presented into the second part of this paper. Let’s mention briefly, though, these formal marks: -pre- determiner that specifies the gender of the noun: I’m not in the market for a male nurse. Whenever possible a female officer deals with female criminals. -compound words using an element that denotes gender: It was ironic that during an Irish debate an Englishman had demonstrated such affection for a Scotsman. Three teenagers who attacked a policewoman were hunted yesterday. -the use of certain suffixes that denote gender: Actor John Travolta was in a bad mood during the shooting. Actress Vanessa Redwood has arrived in Macedonia. The gender of the nouns in Romanian and even in English can be identified in several ways; there are different ways of marking the opposition masculine- feminine- neuter. The gender of the nouns in English is very rarely marked formally as compared to the nouns in Romanian where the meaning and the ending of the noun have a great contribution to the identification of the grammatical category of gender. Except for a few cases when the gender is marked by the use of different words or suffixes (boy- girl, lion- lioness), the gender of most English nouns is identified by using pronouns or adjectives that have a different form for each gender. The doctor is sitting at his desk. He’s writing something. The doctor is standing near her chair. She’s watching my blood test results. 2.Gender mark in Romanian There are three genders in Romanian: masculine, feminine and neuter. The opposition masculine- feminine corresponds to the difference of sex in very few cases, especially the animate nouns and particularly the names of person. This concordance is valid not only for common nouns but also for proper nouns: Ioan/ Ioana, Alexandru/ Alexandra. There are situations when the concordance between the grammatical gender and the sex is not respected any more. Such nouns as “ministru” and “ambasador” have got a form of feminine “ministra” or “ambasadoare” which is very rarely used, the masculine form being preferred when rendering the idea of feminine as well and in order to express the idea of feminine we use appellatives placed in front of the noun and marking the feminine gender: Doamna ministru a semnat documentul azi de dimineata. Except for the case of nouns denoting animals, there is no connection between the grammatical gender and the sex. The grammatical gender is justified in the other cases only by the ending. The criterion of its ending is decisive when considering nouns as belonging to one gender or another. There are no strict rules about it but one, which says that no noun ending in a consonant can be feminine, it is either masculine or neuter. But this rule cannot be applied the other way. A noun ending in a vowel can be masculine (popă, frate), feminine (casă, carte) or neuter (nume, taxi, fotoliu). 279 There are several ways of the gender identification: as C. Dumitriu5 suggests, it can be made by taking into consideration the article, as “Gramatica Academiei Limbii Romane” suggests 6 by attaching a cardinal numeral, as Valeria Guţu- Romalo suggests7 by attaching a demonstrative adjective or, eventually, by using any determiner as Mioara Avram thinks that “ the gender of a noun is marked and can be identified through the form of its determiner”8. It is almost impossible to evaluate the gender of a noun according to its meaning because the names of objects, the abstract nouns and the names of places could belong to any of the three genders. However, there are some remarks we should make. Most of the inanimate nouns are neuter: pahar, dulap, frigider, obraz, piept, drog, ajutor. They can be masculine as well: cartof, perete, pom, dinte. Some of them, but not very many, are feminine: pijama, ţară, capcană, cafea, etc. The names of sports and games are also neuter: box, fotbal, şah, as well as the names of winds: austru, ciclon, crivăţ. Among the nouns that are always masculine we mention: all the letters of the alphabet (a,b, c), the names of months (aprilie, iunie, mai) and the musical notes (do, re, mi). Among the nouns that are always feminine we mention the names of continents (Europa, America, Asia), the days of the week (luni, joi, vineri), the names of the seasons (vara, iarna), most names of fruits (pară, cireaşă, caisă). The exceptions are the following names of fruits that are masculine (strugure, pepene, ananas) and (măr) that is neuter. As for the names of the countries, those ending in “–a” are feminine (Italia, România, Grecia) and those ending in a consonant or another vowel are masculine (Irak, Congo, Peru). Another remark that we have to make in order to identify and to use correctly the gender of the nouns connected to car brands is the following: the noun “car” is feminine, when the car is named as its brand, the gender differs in function of its ending of the word indicating its brand. If the word ends in a vowel, the brand is considered as feminine whereas when it ends in a consonant, the brand is masculine: Şi-a cumpărat o Dacia/ Toyota albă. Şi-a cumpărat un Ford/ Renault verde. The difference in gender is made by selecting a masculine or a feminine article and by agreeing the adjective and the noun. The nouns denoting animates, whose grammatical gender corresponds to their natural gender, can be divided into two classes on the grounds of the way they express the semantic and grammatical distinction of gender. Thus, we have the first class of animates that includes words which form lexical pairs, different in gender (masculine- feminine) and the second class is made of nouns which have a single gender form, corresponding to some semantic particularities concerning the sex of the referent. The first class is also named class of mobile nouns while the second is named the class of epicenes. Many of the feminine nouns are obtained by adding suffixes to their masculine form. Among these suffixes, we mention: -ă: coleg/ colegă, vecin/ vecină -iţă: frizer/ frizeriţă, doctor/ doctoriţă The feminine form of “doctoriţă” is never used for indicating the title or for direct addressing. We shall always say, thus: Doamnă doctor, aţi avut dreptate. Doamna doctor Ionesc lipseşte azi. C. Dimitriu, Gramatica limbii romăne explicată, p. 129 ***, Gramatica limbii romăne. Cuvântul, p. 58-59 7 V. Guţu- Romalo, Substantivul, p. 146 8 M. Avram, Gramatica pentru toţi, p. 32 5 6 280 We shall never address to someone using “Doctore!”, either for a man or a woman, we shall say “Doamnă/ Domnule doctor!” When referring to a scientific title, the noun “doctor” does not have a feminine form. Doamna Ionescu este doctor în matematică. The masculine nouns obtained with the help of the suffix “-tor” are the starting point for the feminine gender, obtained with the help of the suffix “-toare”: învăţător/ învăţătoare, muncitor/ muncitoare, vânzător/ vânzătoare. The suffix “-că” is added to the masculine form in order to obtain a feminine gender noun denoting a person: ţăran/ ţărancă, bucureştean/ bucureşteancă, ţigan/ ţigancă. This suffix can be used exclusively for nouns denoting persons, thus we shall never say “ limba româncă” but “limba română”. The feminine form of the nouns denoting animals or feminine members of a people is obtained by adding the suffix “-oaică”: lup/ lupoaică, leu/ leoaică, turc/ turcoiacă, grec/ grecoaică. There is another suffix, quite rarely used, which helps us to form the feminine gender of a noun, that is “-easă”: lăptar/ lăptăreasă, croitor/ croitoreasă, mire/ mireasă. The few nouns ending in –easă are borrowings from French: poetesă, negresă, prinţesă. Some of the nouns have got a completely different form for feminine: berbec/ oaie, pisică/ motan, cocoş/ găină, ginere/ noră, etc. Besides all these types of nouns previously presented, there are other nouns that form their masculine starting from the feminine. These nouns are derived with the suffix “-oi” and they denote names of animals and birds: cioară/ cioroi, broască/ broscoi, vulpe/ vulpoi. These masculine names are used in every day conversation only if the speaker wants to emphasize the idea that he/ she is talking about a male of the species. As a generic term, the form of feminine is used. Another suffix added at the end of a feminine noun in order to express the idea of a male animal from a species is “-an”: curcă/ curcan, gâscă/ gâscan, ciocârlie/ ciocârlan. To express the idea of a male or a female when talking about nouns that have a single form for both masculine and feminine we may use the words: mascul or femelă: o panteră mascul, un elefant femelă. In Romanian, as well as in English, there are nouns that have only one form either for masculine or feminine gender. Words like: şarpe, jaguar, hipopotam, râs or rinocer have only a masculine form while words like: lamă, pumă, panteră, girafă, hienă have only a feminine form. Certain Romanian words denote a masculine person, in spite of having a form of feminine gender, we may give the following examples: ordonanţă, santinelă, strajă, papă. But, there are masculine nouns denoting both a male or a female person: ascendent, descendent. Ea era singurul descendent în viaţă. A few Romanian words have a double singular form, one masculine and the other one feminine, but they keep the same meaning for each gender form: cătun/ cătună, colind/ colindă. The standard language prefers though the first alternative of the pair. But, when referring to the following words: axiom/ axiomă, bonet/ bonetă, basc/ bască, the standard language would rather use the second term of each pair. The specialized, technical language tends to create a form of plural, masculine for words that are normally used as neuters: robineţi, izolatori, suporţi, vagoneţi, conductori. The standard language uses however their plural form of neuter: robinete, izolatoare, suporturi, vagonete, conductoare. Sometimes there is a difference in meaning according to their masculine or feminine form: fascicul= ray of ight, fascicolă= a certain number of pages from a publication. In the case of a reduced number of nouns, the two different forms have also different plurals with different meaning: Sg. corn - pl. corni (masculine) “musical instrumentl” -pl. cornuri (neuter) “small courved bread” 281 -pl. coarne (neuter) “bone formation on the head of animalsr” Sg. ochi - pl. ochi (masculine) “the organ of sight” -pl. ochiuri (neuter) “scrambled eggs” Sg. colţ - pl. colţi (masculine) “long,sharp teeth of animals” -pl. colţuri (neuter) “geometric angles” Sg. timp - pl. timpi (masculine) “steps in motions” -pl. timpuri (neuter) “time” Sometimes we accept other variants of gender form than the usual one when we use these words into expressions, for example: câmp (pl. câmpuri) but used with the masculine form of plural câmpi in expressions, such as “a bate câmpii” or “a-şi lua câmpii” . 3. Gender mark in English As far as the classification of English nouns into masculines, feminines and neuters is concerned, they are classified into three groups of nouns: names of persons, names of animals and names of objects. a) The gender of the nouns denoting persons- the nouns indicating a male person belong to the class of masculine nouns (man, father, boy), while those indicating a female person belong to the feminine gender (woman, mother, sister). Nouns like baby, infant, child belong to the neuter gender in a pejorative meaning or into a neuter expression from the affective point of view, but there are also words that belong to the common gender (assistant, attendant, driver). They get a different gender in a well- expressed context where the elements, such as pronouns and pronominal adjectives are used with different forms indicating thus the gender. The gender can be lexically or morphologically marked for the class of nouns denoting persons or it can be identified with the help of some words from the context expressing gender. Lexically, the opposition of gender is marked by the use of different words: Masculine Feminine boy . girl father mothe) earl countess gentleman lady king queen lad lass man woman monk nun Mr. Mrs., Ms. nephew niece uncle aunt son daughter husband wife bachelor spinster wizard witch There are in English very many compound words with “man” and “woman” which denote the opposition masculine- feminine. In “Longman Dictionary of English”9 there are about 40 different words compound with -woman and even more compound with –man. Among the most often used ones we mention: spokesman/spokeswoman, policeman/policewoman, 9 D. Biber, S. Johanson, G. Leech, S. Conrad, E. Finegan, Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English, p.313 282 chairman/chairwoman, businessman/businesswoman, congressman/congresswoman and horseman/horsewoman We have to mention the fact that there are several compound words with –woman which do not have a masculine equivalent. Some of them are: beggarwoman, slavewoman, ghostwoman, needlewoman, sweeperwoman. But, on the other hand, there are masculine words compound with – man which do not have a feminine equivalent: airman, barman, boatman, cabman, coalman, craftsman, etc. In many other cases words which have distinct forms for expressing masculine or feminine gender, may become nouns of common gender: father (masculine), mother (feminine), parent (common); king (masculine), queen (feminine), monarch (common); boy (masculine), girl (feminine), child (common); husband (masculine), wife (feminine), spouse (common), etc. Some English words mark their gender through a suffix with a masculine form. When we add this kind of suffixes in order to form a feminine noun, there are sometimes but not always certain changes in the spelling of the masculine word. There are no changes when we add the suffix –ess in order to form the feminine of the following words: god/ goddess, actor/ actress, ambassador/ ambassadrice, heir/ heiress, host/ hostess, etc. When we add the same suffix to other words there are vocalic or consonantal alternations: duke/ duchess, master/ mistress, murderer/ murderess. Except for the suffix –ess there are other suffixes commonly used in English in order to express the feminine gender. Among these we have to take into consideration the following ones: ine, -ette, -ix: hero/ heroine, usher/ usherette, executor/ executrix, etc. As we have already noticed all the situations previously presented refer to nouns, which form their feminine by adding a suffix to the masculine form. There are, though, certain suffixes, which are added to the feminine form of the noun in order to obtain its masculine. Two of these suffixes are –er and –groom: widow/ widower, bride/ bridegroom. Numerous nouns denoting persons have only a single form both for referring to masculine and feminine. They belong to the common gender: artist, cousin, doctor, friend, neighbour, professor, student. We can infer only from the context what gender they are. The gender is expressed by: - pronouns: The teacher asked the pupil a few more questions, as she wanted to give him extra credit. - other words bearing a lexical mark, such as: boy, girl, male, female, man, woman: boyfriend- girlfriend, male student– female student, policeman-policewoman; - with the help of other adjectives specific to only one of the two genders: My neighbour is pregnant. In everyday conversation, especially in the American English, there is a tendency to eliminate the gender mark when talking about jobs in order to avoid the “domination” of one of the two genders or not to emphasize the difference in gender/ sex: traditional use current use Actor,actress actor postman mail carrier fireman fire fighter policeman, policewoman police officer chairman, chairwoman chairperson spokesman, spokeswoman spokesperson air hostess flight attendant mankind human kind b) The gender of nouns denoting names of animals- in English the nouns denoting animals are divided into gender classes according to their size. Thus, big animals are considered masculine and they can be replaced by the masculine pronoun “he”. 283 The mare whinnied when she saw her master. The horse was rather restive at first but he soon became manageable. The mark of gender for big animals is made lexically and morphologically. Lexically, there is a generic term denoting the common gender and two forms for masculine and feminine: Morphologically, the feminine nouns are formed, just like the nouns denoting persons, by Common gender Masculine Feminine addi Horse Stallion Mare ng Ox Bull Cow the Pig Boar Sow suffi Deer Stag Hind x – ess: lion/ lioness, tiger/ tigress. The nouns denoting small animals are considered as neuter nouns and they are replace by “it”. I saw a frog by the lake. It was big and ugly. We can indicate the difference of sex with the help of different words which are gender markers: -different words for each gender: masculine feminine cock hen dog bitch drake duck gander goose -using gender marking words: masculine feminine cock sparrow hen sparrow he- goat she- goat tom- cat tabby- cat male frog female frog he- bear she- bear jack- ass penny- ass 4. Conclusions In both languages there are three classes of nouns divided according to gender: masculine, feminine and neuter nouns. The class of masculine nouns includes animates of male sex (both in Romanian and English) and names of objects, inanimates, which according to tradition or through a logical analogy are considered to be masculine (only in Romanian). The class of feminine nouns includes names of being and animals of female sex (in both languages) and names of objects, inanimates, which according to tradition or through a logical analogy are considered to be feminine (only in Romanian). The class of neuter nouns includes nouns that denote inanimates (in English and in Romanian) and nouns having a generic or collective meaning referring to beings. 284 The nouns denoting beings and animals mark the opposition masculine- feminine in the following ways: using different words for masculine and feminine or using suffixes, procedure known as motion. The nouns that mark their gender using the above mentioned ways are included in the class of mobile nouns while those which keep the same form are known as epicenes. They show that even talking about beings sometimes there are situations when there is no connection between the natural sex and the grammatical gender. Another aspect presented in the paper is the common gender, a generic value of a certain number of nouns, denomination that does not take into account the actual difference among the members of that notional aria, but this notion seen as a whole. In order to establish the gender of noun we have to have in mind its desinence, the linguistic context and its determiners (articles, pronouns, adjectives). Bibliography ** Gramatica limbii române, Academia RPR, Institutul de lingvistica, vol. I Vocabularul, fonetica si morfologia, vol. II Sintaxa, Bucureşti, Ed. Academiei, 1954 (sub redactia prof. Univ. Dimitrie Macua) ** Gramatica limbii române, Ediţia a II-a revăzută si adăugită, vol. I Morfologia, vol. II Sintaxa, Bucureşti, Ed. Academiei, 1963 si 1966 (sub redacţia acad. Al. Graur) ***Gramatica limbii române. Cuvântul, Ed. Academiei Române, Bucureşti, 2005 AVRAM, Mioara, Gramatica pentru toti, Bucureşti, Ed. Humanitas, Editia a III-a, 2001 AVRAM, Mioara, Studii de morfologie a limbii române, Bucuresti, Ed. Academiei, 2005 Biber, David, Johanson, Steven, Leech, George, Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English, Longman, 2000 CHIRIACESCU, Adriana., The noun and determiners, Bucuresti, Editura Teora, 2003 DIMITRIU, Corneliu, Gramatica limbii române explicata. Morfologia, Ed. Virginia, Iasi, 1994 GALATEANU-FARNOAGA, Georgiana, COMISEL, Ecaterina, Gramatica limbii engleze, Ed. Lucman, Bucuresti, 1999 GUTU- ROMALO, Valeria , Morfologie structurală a limbii române (substantiv, adjectiv, verb), Ed. Academiei RSR, Bucureşti, 1968 LEVITCHI, Leon, Gramatica limbii engleze, Bucureşti, Ed. Didactică şi Pedagogică, 1971. 285