Australia`s Trade Remedy System - Best Practice Regulation Updates

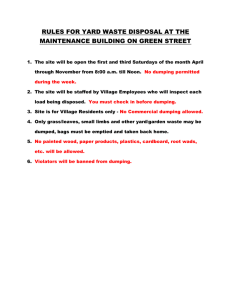

advertisement