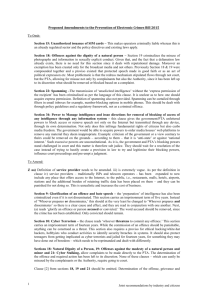

A Guide to Framing Commonwealth Offences, Infringement Notices

advertisement