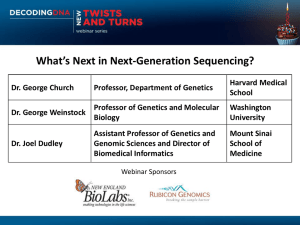

Group one: Sequence results - Department of Genetics at Harvard

advertisement

personal genetics education project – genome sequencing scenarios www.pged.org Scenario A : You have just received a copy of your personal genome sequence. Included in the results is this piece of information: You have tested positive for Huntington’s Disease – a degenerative neurological condition that can strike as early as in one’s 30s or 40s. If you have the mutation, it is 100% certain you will get this disease. You relieved to have an answer, but are also very upset and distressed to have these fears confirmed. You are seeking support from friends and family. Her father, your grandfather, died from HD and his illness was a source of fear and confusion. She has decided she would rather not know. She feels that since there is no treatment or cure for Huntington’s, what’s the point of learning if she carries the mutation? She is also concerned about losing her job. Because Huntington’s is an autosomal dominant condition, your positive status for the gene mutation implicates your mother: It means she will definitely have the disease. You are 19 years old, she is 45. Discussion points: How do you handle this piece of information with your mother? If you tell her that you have the mutation for Huntington’s, you are also telling her that she has it as well. You know she doesn’t want to know – but you need her emotional and financial support. Do you tell her? What are the ethical issues at play? How might this information change your life, and the lives of the other members of your family? When is the “right” time to share this information with friends or the person you are dating? personal genetics education project – genome sequencing scenarios www.pged.org Scenario B: You have just received a copy of your personal genome sequence. Included in the results is the following piece of information: You are a “fast metabolizer” for a prescription drug that you take to prevent a potentially fatal stroke. This helps you choose the right dosage, making it more effective. You also learned you are at above average risk for a heritable form of macular degeneration that can lead to blindness. This is distressing as you are paying for college via ROTC and plan to enter the Air Force as a pilot. After receiving your results, you notice a “macular degenerators” group on Facebook (408 members, last accessed 2/1/2010). Some are donating their DNA to various research projects, offer support to each other, and members share information and treatment plans, and review doctors and hospitals – a sort of www.ratemyprofessor.com for the medical world. Discussion points: Would you join a Facebook group for “macular degenerators”? What about BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, or Huntington’s Disease (350 members, last accessed 2/1/10)? Do you have concerns about the impact of sharing your genetic data for each of these conditions? Why or why not? How do you balance the importance of social networking, research and activism with the need for personal privacy? Ten people have posted their full genetic sequence online, along with their names, medical history, health records, and photographs (www.personalgenomes.org). They feel that making their information public will enable the scientific community to make new connections between genes and traits, as well as turn the idea of genetic privacy upside down. Would you consider this option for yourself? personal genetics education project – genome sequencing scenarios www.pged.org Scenario C: You have just received a copy of your personal genome sequence. Included in the results is following piece of information: You have a mutation on your APOE gene that is strongly associated with an elevated risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. It is a progressive, degenerative disorder of the nervous system, and there are no clinically accepted treatments or cures. Carrying the APOE mutation does not 100% guarantee you will actually develop this typically late-onset (50’s or older) disease. You watched your grandmother suffer for many years with Alzheimer’s, and also a great aunt, and your family struggled emotionally and financially to make sure they had the right medical attention and a safe and comfortable living situation. Discussion points: Will knowing about your risk for Alzheimer’s change how you think about your future? How might it impact your plans for career, family, or travel? You have decided to get sequenced while in college – you are 19 years old. Are you glad to have learned this information so young? How might it have been different if you were 59 when you learned about your genome sequence, as opposed to being a young adult? Knowing this information now, do you have an obligation to share this information with your relatives? What about someone you are dating? When is the right time to mention something like this? personal genetics education project – genome sequencing scenarios www.pged.org Scenario D: You are dating someone and it is getting serious. You see an online ad for a service that offers a sort of “ compatibility testing”, from a health perspective. You both can learn, for free (its covered by insurance), whether or not you are at risk for various diseases, as well as learn about the possible health issues any children you may have could face. Do you go ahead with the testing, knowing it might destabilize your relationship and you may end up breaking up? What kinds of things could you learn – either reassuring, neutral, or worrisome? Is there a stage of your life that is the “ ideal” time to have your genome sequenced? personal genetics education project – genome sequencing scenarios www.pged.org Scenario E: The Personal Genome Project (www.personalgenomes.org) is looking for volunteers to have their genome sequenced as part of a research study. There is no cost to participate. In addition to your complete genetic profile, you are asked to share your complete health history, family medical history, and be photographed. Included in the record is everything from medicines you have taken, personal history, history of drug and alcohol use, along with things like height, weight, etc. The larger goal is to see how your genes (genotype) are related to your physical appearance, actions, and environment (phenotype). Researchers believe the greatest scientific benefits will come if you agree to share all your data fully and openly – with the general public as well as the established research community. However, they do offer the option to keep some of the personal information private – but cannot absolutely guarantee it. What are three major reasons to sign up, and three significant risks of participating?