CQ Researcher Offshore Drilling

advertisement

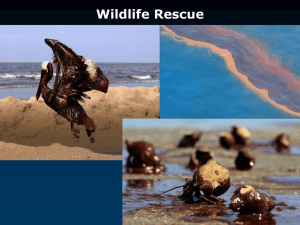

Offshore Drilling Is tougher federal oversight needed? By Thomas J. Billitteri Fire boats try to save the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico on April 21, 2010, a day after a blowout and explosion killed 11 workers. The $550 million floating platform sank on April 22. The resulting oil spill is considered among the worst environmental disasters in U.S. history. (Getty Images/U.S. Coast Guard) June 25, 2010 • Volume 20, Issue 24 Introduction The blowout two months ago at the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico has turned into one of the worst environmental catastrophes in U.S. history. Well owner BP failed in repeated attempts to stop the undersea gusher spilling millions of gallons, and experts say it may be months before it is brought under control. The blowout has exposed corner-cutting by BP and massive regulatory failures at the Minerals Management Service, the federal agency charged with overseeing the 4,000 offshore drilling facilities in the Gulf. The spill also has laid bare ideological differences over national energy policy and heightened debate over how to balance environmental protection with the economy's dependence on oil. Pressed by President Obama, BP promised to set aside $20 billion to pay damage claims. Still, the White House has been at a loss to stem political fallout from the disaster, which ultimately may help define the Obama presidency, much as Hurricane Katrina helped define the legacy of George W. Bush. Go to top Overview On April 20, BP managers were on board the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, some 50 miles out in the Gulf of Mexico, to mark the big floating rig's safety record. But the celebration was short-lived. At 9:56 p.m., a giant burst of methane gas suddenly blew out of the seabed nearly a mile below and shot up the rig's drill pipe toward the surface. Three stories above the rig's steel deck, crane operator Micah Sandell was in his cab when a roaring gush of mud and water rocketed up the derrick, accompanied by the menacing shush of escaping gas. Seconds later, a massive explosion knocked Sandell to the floor and engulfed the tiny cabin in flames. Sandell started to clamber down a ladder, but a second explosion knocked him 25 feet to the deck. “I took off running,” he recalled. “How, I can't tell you.” Eleven oil workers perished in the blast. Sandell and 114 others survived. After finally making landfall aboard a rescue ship, Sandell said, “To me it all felt like a nightmare” To the nation, too, the BP disaster has been a nightmare, one already considered among the worst environmental disasters in U.S. history. The spill has become a protracted spectacle of lurid ecological destruction stretching from southern Louisiana to Florida's Panhandle, and some computer models suggest it could extend along hundreds of miles of Atlantic coast this summer. “Our best knowledge says the scope of this environmental disaster is likely to reach far beyond Florida, with impacts that have yet to be understood,” said Synte Peacock, a scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research. The spill also has exposed massive regulatory failures, laid bare ideological differences over national energy policy and tested the federal government's ability to handle a national emergency. In the end, the calamity is destined to help define the Obama presidency, much as Hurricane Katrina shaped the legacy of George W. Bush. Government scientists said in mid-June that up to 60,000 barrels of oil — about 2.5 million gallons — could be flowing into the Gulf each day. That means an amount equal to the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill in Alaska could be occurring roughly every four days — far above BP's 5,000- An oil-covered pelican is taken to a rehabilitation center in Buras, La., on June 9. Some scientists say the millions of gallons of oil polluting Gulf waters and wetlands could devastate the marine food chain and fragile shoreline ecosystems. Pressed by President Obama, BP has pledged $20 billion for damage claims. The company hopes to complete drilling a pair of new wells by August to stop the spill, now gushing an estimated 2.5 million gallons of oil daily. (AFP/Getty Images/Saul Loeb) barrel original estimate. BP chief executive Tony Hayward says the company is trying to capture as much oil as possible, but it may well keep flowing until at least August, when the company hopes to complete a pair of relief wells. As a “spillcam” showed live television footage of the gusher, Coast Guard Adm. Thad Allen, the government's crisis commander, described the disaster as “a siege across the entire Gulf.” The consequences for the environment are “extraordinarily serious,” says Kierán Suckling, executive director of the Center for Biological Diversity, an advocacy group in Tucson, Ariz. Scientists worry about a massive collapse in the marine food chain, permanent damage to fragile shoreline ecosystems and serious health effects from a million gallons of chemical dispersant BP has sprayed into the Gulf in an attempt to break up the oil. Already, scientists have detected massive plumes of underwater oil miles from the wellhead and ominous oxygen-starved dead zones in the Gulf. What caused the blowout has yet to be officially determined, though BP has been widely accused of cutting corners and ignoring safety warnings in the run-up to the disaster. President Barack Obama ordered a safety review of offshore drilling and the causes of the blowout, led by former Sen. Bob Graham, D-Fla., and former Environmental Protection Agency administrator William Reilly, a Republican. And after a trip to the Louisiana Delta, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said he would “prosecute to the full extent any violations of the law” in connection with the spill. Obama has blamed the spill on “a breakdown of responsibility on the part of BP and perhaps others.” Congressional investigators, relying on internal BP documents, said the company appeared “to have made multiple decisions for economic reasons that increased the danger of a catastrophic well failure.” They suggested “that BP repeatedly chose risky procedures in order to reduce costs and save time and made minimal efforts to contain the added risk.” But Obama and his administration also have been the target of stinging criticism in the aftermath of the spill. Many Americans have expressed dissatisfaction with the pace and cohesiveness of the administration's response and with the president's leadership and command presence. In mid-June, BP bowed to White House pressure and agreed to set aside $20 billion in an independently administered fund to compensate people and businesses for damages. Those damages could run into the tens of billions of dollars, according to some estimates. In the face of withering questioning, Hayward told a congressional hearing on June 17 that the disaster “never should have happened, and I am deeply sorry that it did.” He has vowed BP will pay all “legitimate claims” of damage. But the definition of “legitimate” remains unclear to many Gulf Coast residents and legal advocates. In fact, when the Times of London asked Hayward for examples of illegitimate claims, he responded, “I could give you lots of examples. This is America — come on. We're going to have lots of illegitimate claims. We all know that.” Already, thousands of claims have been filed against BP, many on behalf of fishermen. “It may be a generation before they're able to go out and fish the way they were before,” lawyer Robert Gordon told CNBC. Hayward has remained circumspect about culpability. “A number of companies are involved, including BP, and it is simply too early — and not up to us — to say who is at fault,” he said. Early on, in a highly publicized congressional hearing that Obama denounced as a “ridiculous spectacle” of finger-pointing, BP engaged in a three-way blame game with Transocean — the company that leased the ill-fated rig to BP — and Halliburton, hired to cement the well before the blowout. BP has a weak reputation to stand on. The company has racked up hundreds of safety violations in the past and “has had more high-profile accidents than any other company in recent years,” according to a devastating report by ProPublica, a nonprofit investigative journalism organization. Last year the federal government fined BP $87 million for failing to improve safety at the BP refinery in Texas City, Texas, where an explosion in 2005 killed 15 workers. Not only has the spill put BP under the gun but it also has exposed significant regulatory failures at the Interior Department's Minerals Management Service (MMS), a once-obscure federal agency that regulates offshore drilling . Following on the heels of an MMS sexand-gift scandal in Colorado two years ago, the Interior Department inspector general this spring alleged yet another string of ethical lapses: During the George W. Bush administration, it said, MMS staff members in the Louisiana region accepted energy company gifts, had e-mails containing pornography on their government computers and possibly let drilling companies themselves fill out MMS inspection forms. The report also said an MMS inspector admitted to possibly being under the influence of crystal methamphetamine at work after using it the day before. In what critics call a perverse regulatory model that led the agency to play fast and loose with drilling permits, MMS has been responsible for both collecting drilling royalties from the oil industry and policing that industry. Obama has denounced the “cozy relationship” between MMS and the oil industry, and Interior Secretary Ken Salazar said he would split MMS into three entities with independent missions. But critics say that doesn't go far enough. Since its formation in 1982, MMS has collected more than $210 billion from the oil, gas and coal industries, and others. In 2009, the agency collected $9.9 billion, putting it in the top-10 list of federal revenue generators. (The figure was $24.1 billion in 2008, when oil prices were at an all-time high.) “They had a triple mandate: promote offshore drilling , regulate offshore drilling and get the money from offshore drilling ,” says Enid Sisskin, an environmental activist in Florida and longtime critic of MMS. “You know they're not going to do this well.” Besides putting federal regulators under suspicion, the spill has renewed debate over offshore oil exploration. Just before the spill, Obama endorsed expanding the practice. After the blowout he put a six-month moratorium on deepwater drilling pending a review of safety practices, but on June 21 a federal judge in Louisiana blocked it. The White House said it would appeal. Still, Obama continues to see offshore drilling as an important part of a comprehensive national energy strategy. In the wake of the spill, the administration backed away from halting drilling in shallow water amid complaints that thousands of jobs along the Gulf Coast would be lost. Some environmental advocates want a total ban on new offshore leases. Undersea drilling is “a dirty business from start to finish,” declares Jacqueline Savitz, senior campaign director for Oceana, a Washington-based advocacy group. But others argue the nation's dependence on oil makes a ban folly. “We're not in a position to trade off our addiction to oil with any 12-step program that isn't going to be wildly expensive,” says Jerry Taylor, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank in Washington. Already, though, governors in two key coastal states have switched views. Florida Gov. Charlie Crist, who recently left the Republican Party to run as an independent for U.S. Senate, once supported drilling off the Florida coast but now wants it banned. California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, withdrew support for a plan to allow new drilling off Santa Barbara, where a massive spill in 1969 helped spark the Earth Day environmental movement. “Why,” Schwarzenegger asked, “would we want to take on that kind of risk?” Here are some of the issues being debated in the wake of the spill: Will the spill cause irreparable environmental damage? Many environmentalists and scientists fear an ecological cataclysm stemming from the spill, not only from the oil itself but from the chemical dispersant Corexit that BP has used to treat it. “This is a nightmare,” declared Philippe Cousteau Jr., grandson of the legendary oceanographer Jacques Cousteau, after a dive in the Gulf of Mexico in May. Even before the spill, the Gulf was “heavily degraded,” says Suckling of the Center for Biological Diversity. “This is an ecosystem already highly stressed, [which] means you don't have to push this ecosystem as hard to topple it.” Over the decades, Suckling says, low-level oil spills have polluted the Gulf, which holds hundreds of oil rigs. “It's a huge industrial zone out there,” he says. Indeed, Hurricane Katrina alone released some 8 million gallons of oil from damaged storage tanks and pipelines into inland waterways and wetlands. And pesticides and fertilizer have long washed into the Gulf, creating a dead zone where blooms of oxygenstealing algae choke off marine life. Nancy Rabalais, executive director of the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, told The Washington Post that “you cannot have that much oil on the surface of the water over such a large area without affecting the organisms that live on the upper water column. It's the plankton, the fish larvae, the fish eggs, the marine mammals that live out there, the sea turtles, ocean birds.” And after a two-week study of the spill zone, Samantha Joye, a senior marine scientist at the University of Georgia, said she found levels of methane gas dissolved in deep Gulf waters that were up to 10,000 times higher than normal. The high levels could encourage the growth of microbes that deplete oxygen necessary for marine life. “I've never seen concentrations of methane this high anywhere,” said Joye, who studied samples from an underwater plume she described as 15 miles long, five miles wide and 300 feet thick. “The whole water column has less oxygen than it normally does.” Offshore oil spills don't always result in irreparable damage, notes John W. “Wes” Tunnell, a marine biologist at Texas A&M University who has studied the phenomenon for three decades. In 1979, the Ixtoc 1 exploratory well blew out in 160 feet of water 60 miles from the Mexican coast. Over nine months, 140 million gallons of crude leaked into the Gulf. While entire species weren't lost, up to 80 percent of tiny crustaceans and other shrimp-like organisms perished in the spill zone, according to Tunnell. For 150 miles, oil coated a band of Texas beach 20–30 feet wide. But the oil was largely limited to the beaches and could be cleaned up. Sea life recovered, and to the astonishment of scientists, Tunnell said, the oil simply seemed to disappear over time. “My colleagues in Mexico … tell me they were just totally amazed,” he says. “Two years after that spill, they didn't know where all the oil was. They said it wasn't on the beaches, it wasn't on the bottom [of the Gulf] that they could find, and two years afterward the shrimp fisheries were back up to the same level as before the oil spill. They were pretty well baffled.”