Hatching eggs

advertisement

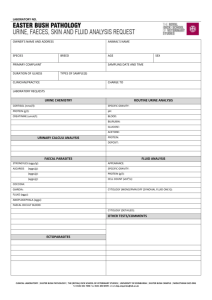

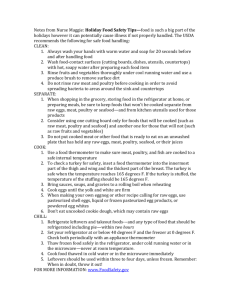

MANAGEMENT OF THE HATCHING EGG Nicholas H.C. Sparks 1, Thomas Acamovic1, Czech A. Conroy2, Dinesh N. Shindey3, and A L. Joshi3 1 Avian Science Research Centre, Animal Health Group, SAC, West Mains Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3JG, UK, 2Livelihoods and Institutions Group, Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich, Central Avenue, Chatham Maritime, Kent, ME4 4TB, United Kingdom and 3BAIF Development Research Foundation, Dr. Manibhai Desai Management Training Centre, Dr. Manibhai Desai Nagar, Pune - 411 052 Abstract Two studies were undertaken in a village in Rajasthan, India. In the first study ten poultry keepers were selected and were given training in identifying infertile and fertile eggs using a locally designed battery operated candler. To monitor the efficacy of the procedure, the eggs identified as fertile or infertile after candling were marked with different colours then incubated. 71.69% of the eggs laid were fertile and 28.30% were infertile (or contained an early dead embryo). Of the eggs that did not hatch, candling identified 50% of the eggs as having cracked shells. The cause of such a high incidence of cracked shells is not known but possible causes are discussed. In a second study the effects of storing eggs at temperatures that were lower and more stable than ambient (achieved by keeping the eggs in bowls kept cool by evaporative cooling) was examined. The cooled storage treatment resulted in 97.2% of fertile eggs hatching compared with the control treatment where 52.3% of fertile eggs hatched. Keywords: village poultry eggs, egg storage Introduction The eggs of the domestic fowl have evolved so that they can be stored for a period of time before they are incubated without necessarily adversely affecting the development of the embryo. This enables the bird to start the incubation process once a clutch has been laid so that the embryos develop at the same rate and as a consequence hatch at approximately the same time thereby maximising the opportunity to benefit equally from the available food resource. Similarly it is not uncommon for Indian village poultry keepers to store eggs before they are incubated, irrespective of whether the egg is to be incubated naturally or in an incubator. However, it has been demonstrated that the conditions under which an egg is stored can have a significant effect on the likelihood of the egg producing a viable chick. There is arguably little benefit therefore in increasing egg production in village poultry by the use of so-called ‘improved breeds’ , or by supplementing the feed that the bird obtains though scavenging, if the eggs are stored in such a way as to reduce hatchability. Following fertilisation in the upper region of the oviduct (infundibulum) the ovum is retained in the oviduct for some 23h during which time it is held at approximately 41.5 oC. This temperature is above physiological zero the temperature at which embryogenesis will occur and consequently embryogenesis proceeds while the egg is formed. At oviposition the embryo will consist of some 60,000 – 120,000 cells. Commercial storage conditions are determined by the environment required to maintain the viability of the embryo at this stage of development. Typical storage conditions would be 15oC, 75%RH with the egg being stored for no more than 7 days. Of these the control of temperature is considered to be the most important. However, for most Indian village poultry keepers, the storage of eggs under controlled environmental conditions is not possible. It is feasible that the poor hatchability associated with eggs stored during the warmer months of the year, when the ambient temperature will exceed physiological zero for poultry eggs (27oC), is the reason that many poultry keepers incubate less eggs during the summer months. A pilot study was devised that would test the hypothesis that ‘storing hatching eggs at a lower than ambient temperature would improve the hatchability of eggs incubated during the summer months’. This study was used as an opportunity to evaluate another intervention, candling. Candling, the shining of a bright light through the shell, allows the stage of embryo development to be approximated. This allows eggs that will not produce a viable embryo (eg infertile eggs, eggs that contain an embryo that has died during the first hours of incubation and eggs that have cracked shells) to be removed before the end of the incubation period to be used as food, livestock feed or sold. The studies took place within the framework of a project is funded by DFID’s Livestock Production Programme. The project is designed to investigate the production problems facing poultry-keepers in two locations in rural India, and working with poultry-keepers to address some of them. The locations, both semi-arid, are Udaipur district in Rajasthan and Trichy District in Tamil Nadu. Materials and Methods Candling trial In an initial trial ten poultry keepers from Jaganathpura village (Udaipur) were trained in candling using a locally designed battery operated candler. During the period 15 November 2002 to 15 February 2003 eggs were candled and marked with different colours to signify either fertilised or unfertilised eggs. All eggs were incubated to allow the accuracy of the candling to be assessed. A second candling trial, with 12 poultry keepers from the same village, was carried out between the months of February and June. Egg storage trial The trial was undertaken (in 2003 during the months of May and June) with 12 poultry keepers being divided into two groups (four in the control group and 8 in the treatment group). Eggs were either stored in the traditional way (control group) or, for the modified storage treatment group, in a half-moon shaped iron bowl (Tagari/ Gamela). The pot was filled with an earth/sand mix which was kept moistened with water. After this a piece of jute bag was placed on the sand, the eggs placed on the bag and then covered with a cotton cloth or woven basket (Figure 1). The bowl was suspended from the roof supports inside a building or placed on a shelf or ledge in a building. The temperature in the vicinity of the eggs and in the egg store room (ambient) was recorded daily (between 08:00-10:00) with a maximum and minimum thermometer. When the hen stopped laying, all the eggs were placed under the hen, as per existing traditional practice. All eggs were candled to confirm fertility. The number of eggs that hatched Figure 1. Cooled egg storage device consisting of an iron bowl, prior to filling with viable chicks, that contained a moistened earth/sand mix and covering with jute sacking dead-in-shell embryos or which had spoiled (infertile or bacterial rot) were recorded. Results and Discussion Candling Study In the first study 71.69% of all the eggs laid were fertile while the remainder (28.30%) were infertile. The error associated with the candling (ie the number of eggs misidentified as either fertile or infertile) was <1%. In the second study the number of fertile eggs was reduced to 62% of all eggs laid. Candling is a technique that is used widely both by the poultry industry, and keepers of other birds, as a means of assessing fertility and embryo development (Delany et al., 1999). The only equipment that is essential to candle eggs is a good light source (such as is provided by a good quality torch) and a darkened room or similar in which the eggs can be assessed. The quality of the lamp is improved if the light source is reduced to an area of ~ 2cm2. In practice this can be achieved by using tape to reduce the area of glass over the bulb which can emit or, 2 preferably by replacing the glass cover with a spare inverted reflector. The light then emerges from the hole (which can be enlarged if required) which originally was designed to take the bulb. Candling eggs has a number of potential advantages, not least of which is that it provides an inexpensive way of identifying eggs that will not produce a viable embryo and which can, as a consequence, be removed early on in incubation (4 - 7 days) for consumption by humans or animals. Our study has shown that ~25% of the eggs placed for hatching could be removed and consumed. While the vast majority of eggs identified as infertile were, in this study area, consumed by the poultry keepers it was notable that some poultry keepers fed the eggs to draught animals when the animal was being used for extended periods of ploughing. Candling allows cracked eggs that may be fertile, but will not support an embryo through the incubation process, to be removed and should make the poultry keeper more aware of the importance of handling eggs in a way that minimises the risk of the shell being damaged. Removal of eggs that are infertile or cracked will increase the apparent success of the hatch but also may increase the actual hatch. The reason for this is that cracked eggs are more prone to microbial spoilage (Sparks, 1993) and, if the egg shell breaks then there is a significant risk of the contaminants contaminating other eggs in the nest. Indeed further research into the high incidence of cracking would be desirable. In summary the use of candling as a means of recovering eggs for human consumption and as a means of improving hatchability should be vigorously promoted by those involved in providing advice and training to poultry keepers who hatch their own replacement stock. Candling has several advantages over many poultryrelated interventions including being utilising simple technology, being relatively inexpensive and potentially being able to make a significant contribution to the nutrition of the poultry keeper and family. Egg storage study Data sets for two of the poultry keepers in the control group could unfortunately not be gathered in their entirety and consequently are not considered further. The data for the remaining farmers are shown in Table 1a and 1b. Of the fertile eggs available for hatching the percentage of chicks that hatched was 95.0 and 69.0% for the modified storage and control groups respectively. While the small sample size in the control group means that the data have to be interpreted cautiously there is a strong indication that the modified storage of eggs did improve the overall hatchability of the eggs set. Indeed these data would be consistent with the hypothesis that keeping the temperature of the egg during storage below physiological zero (27oC) should reduce the incidence of abnormal embryos and the percentage of embryos that die during the first and last weeks of incubation. In this respect it is notable that the minimum room temperature during storage tended to exceed physiological zero and often the maximum temperature achieved was in excess of 320C. These findings are also consistent with those of Walsh et al. (1995), albeit this study used commercial broiler breeder eggs. However it is also possible, although not measured during this study, that some of the apparent improvement in hatchability resulted from a decrease (resulting from the higher humidity levels around the egg) in the water lost from the egg during storage. The contents of the egg are saturated with respect to water and the shell is porous, the porosity being fixed at oviposition (Tranter et al., 1983). The factor that, for practical purposes, is most variable in terms of the rate at which water is lost from the egg tends therefore to be the humidity of the air surrounding the egg. Walsh et al. (1995) noted that the storage of eggs for 14 d at 23.9 C was associated with excessive water loss that was detrimental to embryo survival. It is important that while the sand/soil mix is kept moist - this was achieved by mixing water into the soil approximately every 4 days – the eggs are not allowed to sit in pools of water and that the jute cover should be as free as is feasibly possible from organic contaminants. The reason for this is that the shell and associated cuticle presents a significant barrier to bacteria trying to enter the egg, but water can negate this barrier, allowing bacteria to pass readily along the pore canals into the egg contents. 3 Table 1a: Effect of cooled egg storage on hatchability Poultry No. of No. of chicks Percentage of keeper eggs hatching from chicks hatching identified fertile eggs from fertile eggs as fertile Live Died Live Dead 1 6 6 0 100 0 2 8 8 0 100 0 3 7 7 0 70 0 4 10 8 2 80 20 5 5 5 0 100 0 6 7 7 0 100 0 7 5 5 0 100 0 8 10 10 0 100 0 9 9 9 0 100 0 10 5 5 0 100 0 Total 72 70 2 95 5 Average Room temperature during storage (oC) Min. Max. 27 33 32 36 30 34 29 33 29 34 29 33 28 32 Table 1b: Effect of traditional (uncontrolled temperature) storage on hatchability Poultry No. of No. of chicks Percentage of Average Room keeper eggs hatching from chicks hatching temperature identified fertile eggs from fertile eggs during storage as fertile (oC) Live Died Live Dead Min. Max. 11 9 6 3 66.6 33.3 12 7 5 2 71.4 28.5 28 33.5 13 14 Total 16 11 5 69 31 Further studies are being undertaken to validate these findings. However, the initial findings are encouraging and indicate that a significant improvement in hatchability can be achieved with a relatively simple intervention. When combined with candling, the modified storage technique has the potential to improve both human nutrition and hatchability with relatively little input from, and cost for, the poultry keeper. Acknowledgements The authors are grateful to the UK’s DFID’s Livestock Production Programme for funding this programme of work. SAC receives funding from SEERAD. References DELANY M.E., TELL L.A., MILLAM J.R., PREISLER D.M. (1999) Photographic candling analysis of the embryonic development of orange-winged Amazon parrots (Amazona amazonica). Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 13 (2): 116-123. SPARKS, N H C (1993) Shell covers - their function and structure. In: Microbiology of the Avian Egg. (eds. R. Fuller and R.G. Board) Chapman and Hall. pp 25-42. TRANTER, H.S., SPARKS, N.H.C. AND BOARD, R.G. (1983) Changes in structure of the limiting membrane and in oxygen permeability of the chicken egg integument during incubation. British Poultry Science, 24:537. WALSH T.J., RIZK R.E. and BRAKE J. (1995) Effects of temperature and carbon dioxide on albumen characteristics, weight loss and early embryonic mortality of long stored hatching eggs. Poultry Science 74(9):1403-1410. 4