The Afghanistan Wars. New York

advertisement

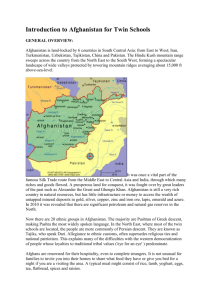

William Maley, The Afghanistan Wars. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. 340 pp. $75.00 cloth; $21.95 paper. Afghanistan's seemingly endless crisis bridges the Cold War and what is now called, for want of a better term, the post–Cold War era. Moreover this continuing crisis has played a major role in the transformation of world politics in both eras. Undoubtedly the Soviet debacle in Afghanistan in the 1980s helped precipitate many of the changes that led to the end of the Cold War. In recent years the importance of Afghanistan to the ongoing war on terrorism is obvious. Hence, the need for a comprehensive review of Afghanistan's wars is equally obvious. William Maley's book admirably satisfies that need. Although the book is not a history of the ongoing combat operations or of the Soviet war, it provides an in-depth political history of Afghanistan from the late 1970s to the early twenty-first century. Maley's bona fides and credentials for this task are first-rate. He has written extensively about Afghanistan and the wars that have plagued the country since the late 1970s, and his notes and assessments show a mastery of the literature on these wars. Throughout the book he is consistently not just retelling the story and analyzing it but also weighing the claims made by various authors and sources about key issues. Invariably, even if one disagrees with his conclusions, his reasoning is sound and coherently argued. His assessments in chapters six and seven of the consequences of the end of the Soviet phase of combat operations are masterful and judicious. Maley has thought about these wars not just from the standpoint of analyzing what went on and why but also from the perspective of the relevant literature on conflict resolution and war in general. This does not mean that all of his judgments are beyond question. I would dispute his assertion on that the survival of the Afghan leader Najibullah after 1989 was due to Soviet support and his enemies' misjudgments more than to anything he did (p. 174). This contradicts the testimony of observers such as Soviet General Makhmut Gareev, Moscow's military representative in Afghanistan, regarding Najibullah's ability (using Soviet resources to be sure) to divide his enemies through the skillful use of [End Page 185] payoffs and bribes during the period from 1989 to 1992. Maley overlooks the fact that the Afghan mujahideen proved unable to move beyond the first phase of guerrilla warfare to capture the main cities of Afghanistan after 1988–1989. At the time, this failure occasioned considerable surprise among foreign observers, who had blithely assumed that without direct Soviet military support the Afghan Communist regime would not long survive. Such caveats aside, the strongest point of this analysis is the political and strategic assessment of the impact of Afghanistan's wars on the country. Until the Taliban takeover in the mid-1990s, there was effectively no government capable of ruling amid the ongoing warfare. Chaotic violence prevailed as elites were unable to come together and establish any sort of consensus about the way the government of Afghanistan would be organized. Not surprisingly, the continuing failure to arrive at an internal consensus created opportunities for uprooted factions, like the Taliban, and for foreign governments with a strategic interest in Afghanistan, like Pakistan, as well as for independent or semi-independent operators, like drug barons, to forge a coalition capable of taking over and enforcing order. In this connection, Maley is rightly scathing about the Clinton administration's feckless policy during the crucial period from 1994 to 1996, when the Taliban were taking over the country. Apparently, the United States once again followed Pakistan's direction in its policymaking toward Afghanistan, thus bringing about a situation directly counter to any reasoned appreciation of U.S. interests or of what Afghan realities were. The fatuity of this policy is deftly skewered by Maley, but of course we are still paying for it today and tragically so. Maley's recommendations for establishing peace in Afghanistan, based on his assessment of the previous generation of wars, have a compelling logic. He emphasizes, first, the need for a genuine elite consensus on the nature of the government the country should have. Only a consensus on this matter will allow for trust among competing tribes and factions and full-fledged efforts to replace the rule of warlords with the rule of a legitimate central government. Once that is achieved, it will be possible to think about and construct democratic institutions and to move seriously ahead in organizing the structure of power, whether along lines of a federal state or through substantial devolution of power to local governments. It will also then be possible to think about organizing new national elections to give further legitimacy to both local and central governments. These are all sound prescriptions and a logical sequence for the creation of a stable, legitimate government with real authority, one that can avoid being torn to pieces by internal rivalries that are then compounded by foreign interventions. However, we are only in the early stages of this process. As of mid-2005 the government led by Hamid Karzai has barely begun to move against the warlords and has not yet taken on the drug trade or fully eliminated the threat of a resurgent Taliban and Al Qaeda groups that are exploiting sanctuaries along the border with Pakistan. Therefore it is too early to tell whether the Karzai government and its backers can put an end to the travails of a generation of war. But if anyone wants to know what happened, what went wrong, and why it is of global importance that an end to these wars be achieved, this book is an excellent place to start. Stephen J. Blank U.S. Army War College