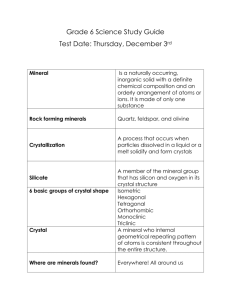

1.2 point defect in ionic crystals and metals

advertisement