Arguments

advertisement

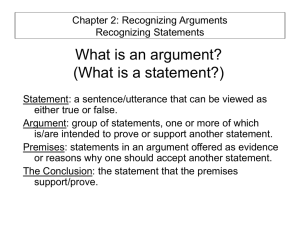

Arguments Definition: An argument is a set of statements which includes a conclusion and at least one premise. The premises are intended to support or establish the conclusion. (In other words, the premises are intended to be reasons for believing the conclusion). Arguments serve two basic purposes: 1) Arguments are a means of inquiry. 2) Arguments explain and defend conclusions. The following are all examples of arguments. Identify the premise(s) and conclusion of each. “The war in Iraq is wrong. It has cost thousands of lives and billions of dollars, and hasn’t made us any safer.” “The war in Iraq is justified. It has rid the world of an evil dictator who used chemical weapons in the past and it will help to bring democracy to the MiddleEast.” “It’s clear that she isn’t interested. If she were, she would have called back by now.” “Herbert will never make it into the state police. They have a weight limit, and he’s over it.” An argument in standard form is a sequence of numbered premises followed by the conclusion. The premises and conclusion are separated by a horizontal line. The above arguments can easily be put into standard form. Example: 1. The state police have a weight limit. 2. Herbert is over the weight limit. _______________________________________________ 3. Therefore, Herbert will never make it into the state police. Whenever there is evidence for or against a claim, we can represent that evidence using arguments. Even ordinary cases of perceptual belief can be represented as arguments. For example: 1. There appears to be a person in front of me. 2. I have a good view of the object in question. 3. I am not dreaming or hallucinating. _______________________________________________ Therefore, there is a person in front of me. The point illustrated by the argument above is that our evidence for a belief can be put into the form of an argument, even if we don’t normally do so. When our beliefs are challenged, being able to formulate arguments for our beliefs is a very useful skill. The ideal critical thinker considers all the evidence, weighs it properly, and then comes to the conclusion best supported by the evidence. We can express the same idea in terms of arguments: when assessing a claim, our job as critical thinkers is to identify the arguments for and against the claim, then evaluate those arguments and reach a conclusion accordingly. Evaluating Arguments An argument is a set of statements which includes a conclusion and at least one premise. The premises are intended to support or establish the conclusion. A good argument justifies the acceptance of the conclusion. But how do we know whether an argument is good? There are two basic questions that we ask when trying to determine whether an argument is good: Question 1: Are the premises true? In most cases, we will not be able to determine with certainty whether the premises are true. Often, though, premises will make claims that are common knowledge, or that can be easily verified or easily falsified. We don’t require absolute certainty when deciding whether a premise is true or false. Some premises are very vague or make claims that are impossible to verify -- we have no basis for judging such premises to be true. Consequently, arguments that contain very vague or unverifiable premises are not good. Question 2: To what extent do the premises support the conclusion? We can put this question another way: How likely is it, on the assumption that the premises are true, that the conclusion is also true? If it is very likely (for example, 95% likely), then the argument is strong. On the other hand, if it isn’t very likely (for example, 50% likely) then the argument is weak. In some arguments, the truth of the premises would make the truth of the conclusion 100% likely. We say that such arguments are valid. We can put this another way: An argument is valid if and only if the premises entail the conclusion. An argument is invalid if and only if it is not valid. Or in other words, to say that an argument is valid is to say that if the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true. Finally, A sound argument is a valid argument in which the premises are all true. In other words, an argument is sound if and only if it is valid and has true premises. If we can be reasonably certain that the premises of an argument are true and that those premises provide strong support for the conclusion, then the argument is good, and we have some justification for believing the conclusion. Examples: So far, Iran has rejected all proposals that would prohibit it from producing enriched uranium, even when support for a civil nuclear energy program is offered in exchange. Next week, European negotiators will make another proposal that would prohibit Iran from producing enriched uranium. Iran will reject this new proposal as well. The above argument is not valid. Even if the premises are true, it is still possible that Iran will agree to the new proposal. However, it is a strong argument. The presidential candidate who receives a majority of the popular vote wins the election. In 2000, Al Gore received a majority of the popular vote. Therefore, Al Gore won the election in 2000. This argument is valid. However, it is not sound because premise 1 is false. You can't buy illegal drugs at the local store. Aspirin, however, is not an illegal drug. Therefore, you can buy aspirin at the local store. Valid? Sound? It is often necessary to “clean up” or otherwise regiment an argument in order to get it into standard form. This process can be useful for clarifying an argument, though we have to be careful not to distort the argument in doing so. “People shouldn’t be forced to pay for things that they don’t want. That’s why taxation is unfair. I mean, look at how the government spends our money…no one wants all of the things our taxes pay for.” 1. People shouldn’t be forced to pay for things that they don’t want. 2. People are forced to pay taxes. 3. There is no one who wants all of the things that taxes pay for. _________________________________________________ Taxation is unfair. In this case, we added a premise and changed the order of presentation to better represent the structure of the argument. Class Activity Construct two arguments of your own: one argument concerning a factual issue, and another argument concerning an ethical issue. Your arguments should satisfy the following criteria: (1) The arguments must be presented in standard form. (2) Each premise should be fairly simple and easy to understand. (3) The conclusion of the argument answer the question posed in the affirmative or negative. For example, “Some people have psychic powers”, or “No one has psychic powers.” (4) If we assumed that the premises were true, then they would provide a good reason for accepting the conclusion (in other words, no weak arguments) Factual Issues Do some people really have psychic powers? Will I get a 3.0 GPA or higher this semester? Did Lance Armstrong take performance enhancing drug EPO? Will rising gas prices cause SUVs to lose popularity? Ethical/Value Issues Should New Orleans be rebuilt with federal funds? Is abortion immoral? Was the invasion of Iraq a mistake? Should same-sex marriage be legalized?