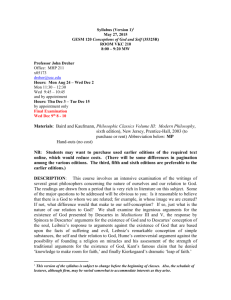

Word

ARLT 100

SYLLABUS v.1

ARLT 100: 35254R

Conceptions of God and Self

Spring 2014

MW 3:30 – 4:50

VKC 154

John Dreher, instructor

Office: MHP 211 x05173 dreher@usc.edu

Hours: Jan 13 – Apr 30

Mon 12:00 – 1:15

Wed 1:00 – 1:45 and by appointment

Last Minute Office Hour for Final Examination

Fri May 9th: 12:30 – 1:45 (MHP 211)

Final Examination : Fri May 9 2:00 – 4:00

Materials : Baird and Kaufmann, Philosophic Classics Volume III: Modern Philosophy ,

third, fourth, fifth or sixth editions), New

Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 2003 (to purchase)

Hand-outs (no cost)

NB: Students may want to purchase used earlier editions of the required text online, which would reduce costs. (There will be some differences in pagination among the various editions. The fifth and sixth editions are preferable to the earlier editions.)

Description : This course involves an intensive examination of the writings of several great philosophers concerning the nature of our relation to God. The readings are drawn from a period that is very rich in literature on this subject. Some of the major questions to be addressed will be obvious to you: Is it reasonable to believe that there is a God to whom we are related? If not, what difference does that make to our self-conception? If so, what is the nature of our relation to God? We shall examine the ingenious arguments for the existence of God presented by Descartes in Meditations III and V, the response by

Spinoza to Descartes’ arguments for the existence of God and to Descartes’ conception of the soul, Leibniz’s response to arguments against the existence of God that are based upon the facts of suffering and evil, Leibniz’s remarkable conception of simple substances, the self and their relation to God, Hume’s controversial argument against the possibility of founding a religion on miracles and his assessment of the strength of traditional arguments for the existence of God, Kant’s famous claim that he denied

‘knowledge to make room for faith,’ and finally Kierkegaard’s dramatic ‘leap of faith.’

2

In addition, we shall be interested in a conceptual revolution that occurred over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. During the early seventeenth century the medieval thesis that faith and reason are essentially complementary remained intact.

By the end of the eighteenth century, however, natural science was thought to threaten religious belief, and by the middle of the nineteenth century many philosophers argued that religion and reason are actually incompatible. Religion, they claimed, requires a

‘leap of faith,’ presumably a leap over the chasm of doubt opened by reason. Many people have thought that substantive scientific doctrine, e.g., Newton’s theory of gravitation or Darwin’s theory of evolution undermined religion. Our course will consider the matter at a deeper level, looking to see how the scientific revolution occasioned crucial changes in concepts like substance, causation, existence and identity and how those changes threatened the medieval synthesis of faith and reason.

Requirements : There will be a midterm examination, which will test for knowledge of the reading assignments as well as the expository and supplementary information delivered during class. There will also be a final examination. The first part of the final examination will test for knowledge of the reading assignments as well as expository and supplementary information delivered during class sessions following the midterm examination. The second part of the final examination will be a comprehensive question dealing with the main theme of the course. The comprehensive question will be discussed towards the end of the semester. Class attendance is very strongly recommended . Please schedule at least one meeting with me during the course of the semester to discuss your work.

There will be three short papers, approximately five pages in length. Recommended topics are:

Paper #1: What is the philosophical problem known as the ‘Cartesian circle’? What is

Descartes’ proposed solution to it?

Paper #2: Compare Descartes’ and Spinoza’s conceptions of substance. Do they

mean the same thing by ‘cause,’ by ‘existence,’ by ‘identity’? How do their

differing conceptions of substance affect their views of God and of the self?

Paper #3: How does Leibniz attempt to show that the existence of God is compatible

with the existence of suffering and evil? Be sure to discuss all eight of the

objections and replies in the (abridgment) of the Theodicy .

You may substitute a paper topic of your choosing for the recommended topic with advance permission. Below are a few alternatives that may be of interest:

ALT Paper #1: What is Pascal’s wager? To whom do you think Pascal’s wager is addressed? What does the wager presuppose about the possibility of knowledge?

2

3

ALT Paper #2: How does Spinoza attempt to deal with the apparent difficulty that

Cartesian philosophy faces in explaining how it is possible for mental and material substances to interact?

ALT Paper #3: What does Leibniz mean by the “pre-established harmony”? How does

Leibniz rely upon it in reconciling his views about physical science with his famous monadology?

Grades will be calculated as follows:

Paper #1 – 1/6

Paper #2 – 1/6

Paper #3 – 1/6

Midterm Exam – 1/6

Final Exam: Part I – 1/6

Final Exam: Part II – 1/6

Please remember that the University strictly prohibits plagiarism, which can be the mere failure to acknowledge the work of another as well as the deliberate misrepresentation of the work of another as your own. You must acknowledge your indebtedness not only to the ideas of others but also to their words.

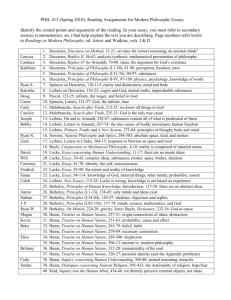

Schedule of Readings, Assignments and Examinations :

1. Mon Jan 13: Introduction: Background of 17 th

and 18 th

century philosophy,

influence of the scientific revolution on epistemology, the rise of

naturalism: Descartes: Dedicatory letter, Preface, Synopsis of the

Meditation, MP 9 – 19 .

2. Wed Jan 15: Descartes, Meditation I: “Demons, Dreamers and Madmen”:

MP 19 – 22.

3. Mon Jan 20: M.L. King, Jr. Day: UNIVERSITY HOLIDAY

4. Wed Jan 22: Descartes: Meditation II: Essence and existence: MP 22 – 27.

5. Mon Jan 27: Descartes: Meditation III: Argument for the existence of God from

the fact of our idea of him: MP 27 – 35.

6. Wed Jan 29: Descartes: Meditation IV: Error as intellectual sin: MP 35 – 40.

7. Mon Feb 3: Descartes, Meditation V: The nature of material things, the

ontological argument: MP 40 – 44.

8. Wed Feb 5: Descartes: Meditation VI and Correspondence of Princess Elizabeth

Self-knowledge and knowledge of the ‘external world’:

MP 44 - 57 .

3

4

9. Mon Feb 10: Pascal: Pensees: The wager: MP 103 – 111.

10. Wed Feb 12: Spinoza: Ethics I: Definitions and axioms: MP 114 – 120 .

11. Mon Feb 17: Presidents’ Day University Holiday

12. Wed Feb 19: Spinoza: Ethics I: P1 – P11: Infinite substance: MP 120 – 137 .

Paper #1 DUE

13. Mon Feb 24: Spinoza: Ethics II: Parallelism MP 137 - 141.

14. Wed Feb 26: Review for Midterm Examination

15. Mon Mar 3: Midterm Examination

16. Wed Mar 5: Leibniz: Monadology : Why simple substance cannot be material.

1 – 13: MP 290.

17. Mon Mar 10 Leibniz: Monadology : Pre-established harmony of final and efficient

Causes: 14 – 90: MP 291 - 298 .

18. Wed Mar 12: Syllogistic Logic

Paper #2 DUE

Mon Mar 17 – Sat Mar 22: Spring Break University Holiday

19. Mon Mar 24: Leibniz: Theodicy : Objections I, II, III, IV: That the existence of

evil is compatible with the existence of God: MP 281 – 287 .

20. Wed Mar 26: Leibniz: Theodicy : Privation and the source of sin and error:

Objections V, VI, VII, VIII: MP 287 – 289 .

21. Mon Mar 31: Hume: Treatise of Human Nature

, ‘Of the Immateriality

of the Soul’: The take-away argument, hand-out.

22. Wed Apr 2: Hume: Skepticism I, Skepticism about causation, ECHU Sections I,

II, III, IV, V: MP 352 – 380.

23. Mon Apr 7: Hume: Skepticism II, Against miracles, ECHU , X, XI, MP 404 – 423.

24. Wed Apr 9: Hume: Against the cosmological Argument and the ontological

Argument, DCNR , Parts IX – XII, MP 463 – 471.

Paper #3 DUE

4

5

25. Mon Apr14: Kant: Critical Philosophy, Preface to the Critique of Pure Reason ,

second edition, MP 513 – 520.

26. Wed Apr 16: Kant: On Substance and Self, The Psychological Ideas,

Prolegomena , MP 590 – 598.

27. Mon Apr 21: Kant: The Determination of the Bounds of Pure Reason,

Prolegomena , MP, pp 584 – 93 .

28. Wed Apr 23: Kant: The Categorical Imperative; the moral foundation of religious

faith

29. Mon Apr 28 Hegel, The beautiful soul; Phenomenology of Spirit ch 6, sect 3,

hand-out; Kierkegaard, The leap of faith, hand-out

30. Wed Apr 30: Discussion of Final Examination Study Questions

30. Wed Dec 5: /Class

Evaluations

Fri May 9 Last Minute Review: Office Hour (12:30 – 1:45; MHP 211)

Final Examination (2:00 – 4:00)

Study Questions

The questions below are designed to help you focus on the most important parts of the readings and lectures. Naturally the topics and questions addressed in the questions are the ones that are most likely to be included on the midterm and final examinations.

There may be additions to the list of the study questions during the semester and the questions themselves may be modified.

DESCARTES

D1. What are the three stages of doubt identified by Descartes in Meditation I? How are they related to each other? What is the purpose of the doubt? Does the fact that a proposition is doubted show that Descartes has a reason for doubting it? (Check out Med

V in addition to Med I before answering this question.)

D2. Apparently, Descartes is satisfied that he is a thinking thing because he has concluded that he exists on the grounds that he thinks. Discuss the significance of this fact for understanding Descartes’s conception of the relation of mind and body.

D3. Reconstruct Descartes’ proof of the existence of God found in Mediation III. Be sure to discuss his famous principle about the formal reality and the objective reality of ideas.

5

6

D4. According to Descartes, error arises when our will extends beyond the scope of our understanding. Why does Descartes insist that error cannot originate in the understanding?

D5. Reconstruct Descartes’ argument for the existence of God found in Meditation V.

Be sure to include a discussion of the significance of the fact that God is eternal in elaborating the proof.

D6. According to Descartes, the doubts that he entertained in Meditation I are not fully warranted once we have come to see that God exists and that he is not a deceiver.

Specifically, how does the existence of God relieve Cartesian doubt?

PASCAL

P1. To whom does Pascal add his famous wager? What is the structure of the wager?

Should the people to whom it is addressed be convinced by the wager argument?

SPINOZA

S1. In Spinoza’s philosophy, how are the concepts of substance, attribute and modes related to each other? Why does Spinoza think that there is at most one substance?

S2. What is Spinoza’s distinction between something that is absolutely infinite and something that is infinite in its own kind? Between something that is finite and something that is infinite? What are the relations between finite extended modes and ideas?

S3. What are the two ways in which we conceive substance? Are there more than two ways in which substance can be modified? What are the infinite modes of substance?

How are the infinite modes related to the finite modes? Do temporal relations extend to infinite modes as well as finite modes?

S4. What is Spinoza’s argument for casual determinism? What role does the concept of a ‘transitive cause’ play in the argument? Is there any sense in which we are free? Is there any sense in which God is free?

LEIBNIZ

L1. What is Leibniz’s argument for his claim that ‘the world’ consists of simple, spiritual substances? How does Leibniz reconcile the existence of matter with his view that the world consists of simple, spiritual substances? According to Leibniz, what is physics about, and what do physical laws describe?

L2. What according to Leibniz is a perception? What sorts of entities have perceptions? How does Leibniz distinguish perceptions from apperceptions? What sorts of entities have apperceptions? What is the role of appetition in Leibniz’s account of choice?

6

7

L3. Leibniz claims that each monad mirrors the universe. How is this claim related to the theory that for Leibniz all relational properties are conceived as intrinsic properties?

What does Leibniz mean by the ‘pre-established harmony.’ Specificially, what does the pre-established harmony harmonize? What in Leibnizian metaphysics is a human being?

L4. According to Leibniz, some influences upon us incline us without necessitating?

What philosophical problem is addressed by this distinction? How, according to Leibniz, is it possible for us to choose freely if all our actions are pre-ordained and foreseen by

God?

HUME

H1. What is Hume’s argument against the existence of substance? How does his argument affect our conception of ourselves, of God? What are Hume’s criticism(s) of the conceptions of substance found in the works of Descartes? of Leibniz? of Spinoza?

H2. What is Hume’s distinction between matters of fact and relations of ideas? Are causal statements matters of fact or relations of ideas? Why? What is Hume’s understanding of causation and how does it differ from the view of causation found in philosophers like Descartes? What difficulties does Hume’s account of causation raise for his theory of personal identity?

H3. What is the essence of Hume’s objection to the claim that the existence of miracles can be the foundation of a religion? Be sure to begin you answer by explaining what

Hume means by ‘a miracle.’ Hume allows, in his example concerning the Indian prince, that an event may be quite extraordinary, beyond anything in the experience of an individual, and yet still NOT be a miracle. How does Hume distinguish between those extraordinary events and miracles?

H4. How does Hume attempt to counter arguments for the existence of God in the

Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion?

Specifically, how does Hume deal with the argument from design, the cosmological argument and the ontological argument?

KANT

K1. What, according to Kant, are synthetic a priori judgments? How are synthetic a

priori judgments related to the pure forms of intuition and the pure concepts of the understanding? How does Kant attempt to justify his claim that every event has a cause?

K2. How does Kant deal with the notion of substance? Is substance a concept in Kant’s sense of ‘concept’? Is substance an object of possible experience? Why does this matter to Kant? What are the consequences of Kant’s views about substance for his conception of the self? for his conception of God?

7

K3. Kant claims that he ‘has found it necessary to deny knowledge, in order to make room for faith.’ (

Critique of Pure Reason , Preface to the Second Edition, p. 513) What is it that Kant believes that we cannot know? What are the objects of faith? How, according to Kant, is it possible for us to think of God?

K4. Kant believes in the determinism of nature and in the free (autonomous) will. How does he attempt to reconcile these two apparently conflicting claims? What are the consequences of his dualism with respect to the self for his views about morality and religion?

HEGEL

H1. How, for Hegel, does the rise of Newtonian science threaten the very conception of the sacred and holy? What is the consequence of the atheism and deism for transcendent moral values? For Hegel, is the ethical possible without the holy? What irony does

Hegel see in the attempt to live a holy life in the post-Enlightenment era? How is that irony relevant to Hegel’s conception of the ‘beautiful soul’?

KIERKEGAARD

KK1. How does Kierkegaard’s philosophy of religion build upon Kant’s understanding of the noumenal realm? Compare Kant’s account of the relation of morality to religion with Kierkegaard’s account of the same.

COMPREHENSIVE

C1. Discuss the role that changing conceptions of substance and causation play in undermining rationalist views of God and the self, and explain how they facilitate the skeptical views of Hume and the critical views of Kant. (Include as much detail and as many references to the text as you can in the limited time that you have to write.)

C2. Contrast Hume’s distinction between relations of ideas and matters of fact with

Kant’s distinctions between analytic and synthetic judgments and between a priori and a posteriori judgments. What are the consequences of their disagreements about these issues for their views about causation? about mathematics? about our knowledge of the phenomenal world?

C3. What distinguishes the Enlightenment as a world-view from the world-view of the

Rationalists? Specifically, how do the two world-views differ with respect to their theories of knowledge and belief? What are the consequences for our understanding of

God and of ourselves?

8

8