Migraine – tension-type headache

advertisement

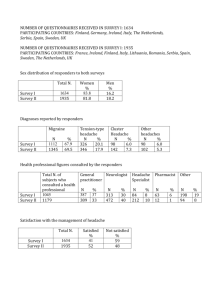

Qigong Yangsheng – Exercises of Traditional Chinese Medicine – in migraine and tension headache Results of a multicentre prospective study Dr. Elisabeth Friedrichs1, Dr. Beate Pfister2, Professor Dr. David Aldridge3 1 General practitioner, Augsburg, 2 Biomathematician, Bonn, 3 Chair of Qualitative Research in Medicine, University of Witten/Herdecke Abstract Objective The aim of this study was to search for indications that qigong exercises can be a useful concomitant treatment of headache and migraine. Methods We studied the effect of selected qigong exercises from “15 Formulas of Taiji Qigong Exercises” by Jiao Guorui as a concomitant treatment of migraine and tension headache. 95 participants (among them 90 women, mostly of middle age) took part for 34 weeks on average. Therapeutic factors of this “active part” of traditional Chinese medicine were considered to be the practising of tension and relaxation, rest and movement as well as imaginative elements. Results In baseline, corrected for 28 days, the number of days with headache (primary efficacy measure) were 8 for the total collective, as opposed to 5 days in follow-up (median, p< 0,001). The median of days with headache per participant was reduced by one day. 27 of the participants (28 per cent) qualify as responders, according to international recommendations, with a 50 or more per cent reduction in days with headache. For the group with 3 to 7 days with headache in baseline, the share of persons with 50 per cent pain reduction is 30 per cent, for the group with 8 to 14 days with headache in baseline, it is 34 per cent. Together, the two groups comprise 75 % of the participants. Secondary efficay measures were “pain intensity” (measured in VAS) and parameters to measure health-related quality of life (HRQOL). They were also found to give statistically significant hints for clinical improvement. Conclusions Supportive evidence from this pilot study suggests that qigong exercises can be a useful concomitant treatment of headache and migraine. Further studies are indicated. Key words: Qigong Yangsheng exercises – migraine – tension headache – pilot study – days with headache – pain intensity – supportive evidence – hypothesis generating Acknowledgements: The study was supported by the German Medical Acupuncture Association (DÄGfA) and the German Medical Association for Qigong Yangsheng. Introduction Headache is a very frequent disorder. The Deutsche Migräne- und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (German Headache Society, E.F.) (Diener et al. 2000) reports an incidence of migraine of 6-8 % in men and 12-14 % in women in Germany. Approximately 29 million people in Germany suffer from tension-type headache (Göbel et al. 1994). Direct costs for migraine therapy are an estimated 478.5 million € (Schmidt 2003, p.60), indirect costs are believed to be considerably higher. Headache therapy with drugs exclusively remains unsatisfactory. On the one hand, it is not efficient enough in many cases; on the other, a specific problem in headache treatment is that patients taking pain medication for acute pain on more than 10 days per month run the risk of developing a “drug-induced headache”. The intake of drugs against acute headache alone – many of them for sale without prescription – may produce headache. Diener (2001) pointed 1 out with great urgency that a “medical overuse headache” may evolve even faster if the acute drug is highly efficient and powerful. With the substance group in use for now 11 years, triptanes that have an effect on migraine in particular, this may be the case after only 1,7 years on average. Prophylactic headache medication on the other hand may have side effects or contraindications as e.g. tiredness and spastic bronchitis in the case of beta blockers. Participants in courses organized by the medical Qigong Yangsheng society have reported for years that their long-term serious headache condition improved considerably. Such individual observations and discussions in the work group “Qigong in Medicine” and also among lecturers of the Medizinische Gesellschaft für Qigong Yangsheng finally led to a formal study into effects of Qigong exercises on headache in 1999. After a preparatory phase, the study was performed between the end of 2000 and the middle of 2002. Migraine – tension-type headache In 1988, the Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) designed a generally acknowledged classification in cooperation with international academic societies; this classification covering 130 types of headache including subtypes was revised in 2004, but the main topics of the classification of 1998 are still valid. The study described below covers concomitant treatment of migraine and tension-type headache. With more than 90 % these are the most frequent primary forms of headache, i.e. not occurring as a consequence of other disorders (Göbel 1998, p. 17). On the basis of the IHS classification for easy diagnosis, Diener developed useful differentiation criteria that were employed with minor variations for this study: Questionnaire on headache anamnesis from Diener, based on International Headache Society Classification, 1988 How often? How intensive? How long? Where? Which type? Which further symptoms? What do you do? Migraine once or twice per month Tension-type Headache episodes: once or twice per week chronic: daily medium to intensive light to medium 4 hours to 3 days more than 5 hours to days unilateral, temples, neck, eye, entire head also bilateral pulsating, throbbing, stabbing dull, oppressive, feeling of having a tight band around the head sickness, vomiting, light and minor sickness sound sensitivity rest in bed, darkness go on working The various theories on pathogenesis of migraine and tension headache will not be discussed in detail; there will, however, be a short reference to the humoral-vascular theory according to which in a migraine attack, serotonin is released, with vasoconstriction followed reactively by vasodilation accompanied by pain (Goadsby, 2001, p. 250). The neurogenic theory interpretes migraine as an integration attempt with disturbed stimulus processing. Migraine patients cannot “switch off”. This means that for migraine patients previous stimuli are experienced as new every time they occur. A migraine attack then is a very tormenting attempt at integration to cope with the disturbed processing of stimuli, something like a “purifying thunderstorm”. Inadequate stress processing, disturbed hormonal balance in women, changes in sleep-wake rhythm, exposure to strong light impulses and environmental 2 factors are mentioned as the most frequent biological factors or environmental influences that might additionally trigger an attack. Only few findings have so far been published on the pathophysiology of tension headache. The German Headache Society lists unfavorable job-related body postures, myofascial oromandibular dysfunctions, psychosocial and muscular stress, alimentary disorders, specifically insufficient fluid intake, irregular life-style and exaggerated performance behavior as causes of disease – comparable to the trigger factors in migraine. Headache from the perspective of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) The focus in Traditional Chinese Medicine is not so much on treatment of isolated clinical pictures: “The main objective in Chinese philosophy and culture is harmony; … experts practicing TCM do not try to isolate one factor causing illness and to attack it but rather to disvover a pattern of disharmony and treat it in such a way that the body is encouraged to recover its harmony unassisted” (Ross 1992, p. 23). Pain may thus be seen as an expression or external sign of disorders whose specific patterns of disharmony must be grasped with the diagnostic possibilities of TCM which are described as follows. From the perspective of Zang Fu, or five phases of change, there are many indications to associate migraine as an illness occuring in attacks with a disturbance in liver functions. External climatic factors inducing illness like the “wind” – that is associated with the liver – or internal factors like anger or rage – ‘trigger factors’ – combined with an instable basis may raise the yang of the liver and thus cause attacks. The eye which is seen as the ‘opener’ or organ connected with the liver is also affected frequently in this context. Among the five most important physiological substances from TCM, I will only discuss the relationship between Qi and blood in some detail here. In the context of a pain condition, a dull pain often to be found with tension-type headache or also with drug-induced headache may be seen as an expression of blood stasis, whereas a sharp acute pain may rather be related to a stagnation of Qi. According to the “eight diagnostic rules” or “Ba Gang”, headache may be related to the polar pairs of criteria emptiness – fullness as a condition of pathological upper fullness and lower emptiness. A certain form of headache called toufeng means “wind in the head” and is described as follows in the classical essay Zhubing yuanhou lun (Engelhardt, 2002), the first official work on medicine written by order of the Emperor in the year 610: “ The presence of wind in the area of head and face is mainly due to an (energetic) emptiness of the body ... with more serious cases, there will be headache” (Despeux, 1995, p. 129). Drug-free headache therapy Drug-free therapies are of increasing importance worldwide as concomitant treatment of headache. Therapy recommendations published by the German Headache Society (Pfaffenrath et al., 1998, Diener et al. 2000) are based on the idea that serious forms of headache in particular require therapies both with and without drugs. Some “drug-free therapies” have been incorporated in these recommendations: Behaviour therapy* Relaxation therapies* Progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobsen* Biofeedback therapies* Endurance sports* Autogenous training Imagination Music therapy Physicotherapies like remedial gymnastics or massage Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) 3 Acupuncture * recommended by the Deutsche Migräne- und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft Pain-relieving effects of Qigong In Traditional Chinese Medicine, Qigong is often considered the active part of acupuncture. Body exercises guided by mental activities and images are intended to help maintain or recover a harmonious state of being. Originally termed “practices for life care”, such training exercises were later called qigong … meaning “work on qi” or simply “qigong exercises”. The scope of meaning of the term “gong” reaches from “success”, “effect”, “work”, or “discipline” to “deserving action”, which according to the Daoist thinking is a “morally commendable act” and as such “scrupulously registered by the heavenly bureaucracy” in the assessment of a candidate (Engelhardt 1997, p.18). Early texts describe headache-relieving effects of individual Qigong exercises. There is e.g. an exercise called “Dongfang Shuo takes off his cap and resigns his post”; the description given for the effect says: Grasping the wind and the thunder with both hands, it is possible to cure such lasting headaches in particular that are produced by the existence of wind in the head (toufeng) and tumors of the brain (hunnao sha) (Despeux 1995, p. 129) The exercise programme and teaching system Qigong Yangsheng – The therapy chosen for this study From the wide range of Qigong exercises now known in Europe as well, this study is based on selected exercises from the exercise programme Qigong Yangsheng according to Jiao Guorui. Professor Jiao Guorui (1923-1997) was a Professor of Traditional Chinese Medicine at Beijing UniversiDongfang Shuo takes off his cap and ty and a Qigong master. He taught Qigong Yangresigns his post sheng in Germany for several years after his retirement. For him, the significance of an appropriate conduct of life, of which Qigong exercises are only one part, was such that he called his teaching and exercise system “Qigong Yangsheng”. The term “Yangsheng” means “nourishing” or “cultivating” life and stands for “art of living” or “conduct of life”; its sources are many and go mainly back to the Tang period (618 to 917). Key points of Qigong practice Jiao Guorui gave a short description of requirements governing his exercise principles of “Yangsheng”, summarized in six so-called key points (1989, p. 60). These principles are presented below from the perspective of headache therapy. Relaxation, rest, naturalness This first requirement refers to physical as well as mental relaxation. “Relaxation therefore does not mean absolute relaxation but rather a pleasant state where tension and relaxation are well-balanced” (Jiao Guorui, 1996, p. 24). Relaxation is the prerequisite for the emergence of tranquillity, in particular equanimity of thinking. Jiao Guorui frequently uses the term “ a hord of wild monkeys” to describe a state of agitated thinking (Jiao Guorui, 1996, p. 24). “Naturalness” permits participants in exercises to adjust the general exercise requirements, e.g. those of body posture, to their own conditions and needs. Imagination and Qi follow one another 4 The term “imagination” is a translation of the Chinese term “Yi”. “Yi always describes an active intellectual activity with specific characteristics and specific contents and qualities as part of Qigong exercises.”1 (1 Hildenbrand in Hildenbrand et al. 1998a, p. 172) In practical exercises the use of the imagination “Yi” provides the chance to influence physiological processes through intellectual activity and imagination. Colourful descriptions of exercises are very helpful in this context, and also for the exercises used in this study. They comprise among other things the image of the deeply rooted pine in the first preparative posture, the tranquillity of the moon in the second exercise, or the lightness of clouds in the fifth exercise. In addition, the exercise “carry the ball to left and right” (3rd exercise) and also the fifth (“horse step – hands like passing clouds”) demand full attention. Thoughts may thus be diverted from pain, an approach that is also deemed important in sports therapy as part of pain management (Gerber et al. 1987). Movement and rest belong together The image of a pine, deeply rooted and calm, is associated with the first preparatory posture “standing like a pine”. This exercises may be practised for short or longer periods as an exercise in external calm. If, however, the external physical tranquillity of this posture produces disagreeable emotions of a physical and also intellectual nature in the practising person, then he or she is allowed and even encouraged to let the pine move just like a real pine moves elastically with the wind. “light” above, “firm” below The principle “lower firmness” may have a counter-effect on the pathological state of headache “upper fullness – lower –emptiness” and continues throughout all exercises. “The proper measure” It is possible and sometimes necessary to adjust exercise conditions to the physical and intellectual capacities of participants. Migraine patients have to be exhorted frequently not to exceed their own potential. This reminds us of therapy principles in behaviour therapy for patients with migraine and also with tension-type headache. Participants should learn to recognize overstrain – whether induced by themselves or by others – in time and to react accordingly. Practice step by step A possible disturbance in processing stimuli for migraine patients has already been mentioned. This would make it difficult to concentrate on one task. The process of learning Qigong exercises, in contrast, requires to do one thing at a time, i.e. to focus on one thing or one exercise exclusively and “step by step” in a defined sequence, and not to bother with the next exercise until later. The physical well-being described by many participants after the first few training lessons might be very helpful. Selected exercises from the “15 Taiji Qigong Exercise Movements” Jiao Guorui designed this sequence of exercises based on the “13 expressions of the Taiji exercise with stakes” described by the legendary Daoist Xu Xuan Ping in the time of the Tang dynasty (618 to 907). I selected the first six exercises from the entire cycle, including preparatory and concluding exercises, for this study. 1. Regulate the breath, quieten the mind/spirit 2. part the clouds, carry the moon 3. Carry the ball to left and right 4. Push the mountain with both hands 5. Horse step – hands like passing clouds 6. The condor spreads its wings The following aspects should be underlined in particular: 5 Images evoked from animated or not animated nature are pleasant and harmonious, comparable to the above-mentioned imaginative procedures. If performed more intensively, these exercises may support the “healthy” conduct of life postulated in sports and movement therapy. The exercises comprise a therapeutic component with regard to the pathological strain present in tension-type headache in particular and thus may help to change over from a sympathetic state to a parasympathetic state. The exercises described here in combination with individual practical experience were the starting-point for a study into the effects of selected Qigong exercises on headache. Methods The study was performed in pursuance of the “Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine, first edition, International Headache Society (IHS) Committee on Clinical Trials in Migraine, first edition (1991)” and the “Guidelines for trial of drug treatments in tension-type headache, first edition, International Headache Society (IHS) Committee on Clinical Trials (1995)”. This applies specifically to definition of target sizes and of procedures including baseline and follow-up, and also to definition of measurement data and criteria, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. However, these recommendations do not contain detailed guidelines for research into “drug-free therapies”. Diagnostic instruments were those usually applied in pain treatment, among others the StK2 questionnaire at the start and three follow-up questionnaires at defined measurement points. (2 StK: Schmerztherapeutisches Kolloquium – Deutsche Schmerzgesellschaft e.V., Adenauerallee 18, 61440 Oberursel. E-Mail: stk.zentrala@stk-ev.de) In addition a pain journal was designed for continuous registration of pain levels and exercise effects. All calculations were standardized for 28 days. Different persons were responsible for study performance, data input and evaluation respectively to ensure maximum objectivity in data acquisition. The purpose of this study was to assess the efficiency, feasibility and definition of appropriate measurement parameters and points in a (single-branch) phase II study. “The results of explorative clinical assessments are no formally unequivocal supportive evidence, but they provide a basis for planning and design of subsequent confirmatory phase III studies” (J.A. Schwarz 2000, p. 144). The purpose of the study was to test suitable measurement methods and to develop hypotheses, not for obtaining evidence. So the objective is hypothesis generation versus validation of the method explored. This definition determines the methods used in evaluation: The group analysed includes all 95 evaluable participants (per protocol) with no differentiation by diagnosis. All of the analyses were carried out descriptively at a non-parametric level. Group-related parameter changes were analysed in a comparison between the individual study phases. Case-related parameter changes were assessed in a comparison between the baseline and the follow-up period and evaluated over the study period using the Friedmann test for hypothesis generation. The study protocol stated 80 as the required number of participants, therefore the multicentre design was planned from the beginning. This was another practical reason to opt for the “15 expressions of Taiji-Qigong according to Jiao Guorui” as therapy. Previous studies by Reuther on the effects of Qigong exercises on asthma bronchiale (Reuther 1997) and Ritter on arterial hypertension (Ritter 2000) also adhered to this sequence of exercises. This sequence is taught by qualified Qigong teachers in weekly sessions at a variety of community institutions, 6 e.g. adult education centres. A sufficient number of course teachers and physicians was therefore ensured. Design study phases, according to the study protocol 4 weeks phase A1 8 weeks phase B1 8 weeks phase C1 8 weeks phase B2 4 weeks phase A2 baseline treatment private training treatment follow-up interval course no course course no course A F1 F2 F3 ………………………………………………………………………………..partial reimbursement of course fees ……. . Headache diary A pain anamnesis questionnaire F1-F3 follow-up questionnaire Explanation: After an interval of four weeks, the baseline, the therapy begins as a course. The first six exercises from the 15 expressions of Taiji Qigong are taught on 8 days, once per week for 90 minutes respectively. Phase C1 covers private training, phase B2 is a repetition identical with phase B1, to be concluded by phase A2, the follow-up. Upon submission of the last completed course documents, participants will be reimbursed with part of the fees. Results General remarks on characteristics of participants and on the study The study was performed between the end of 2000 and spring of 2002 at a total of 11 locations, with 13 teachers and several physicians. The required minimum number of participants calculated in advance was ensured. 36 participants from a total of 95 test persons presented “migraine”, 22 “tension-type headache”, 37 a “mixed form” of both. A comparison of evaluable participants and drop-outs shows that these collectives according to age (44 years median, from 21 to 63), gender (90 of 95 test persons are female) and diagnosis did not present any significant differences. Dropouts do not differ in this respect from participants who completed the study. No specific subcollective formed for these categories in the course of the study, compared to the beginning. The baseline median was 8 days with pain for test persons (per 28 days, from 1 to 28), 13 test persons took prophylactic pain medication. Significant results Number of days with headache per 28 days study phase (primary efficacy measure) The median of the number of days with headache (primary efficacy measure) per 28 days study phase, related to the evaluation collective, was reduced from 8 days at baseline to 5 days in follow-up. Related to individual case, the median of days with pain decreased by one day (see the 2 tables below: "The main results" ). Graph 1 shows the consolidation of the entire collective towards a smaller number of days with headache: 7 Number of days with headache per 28-day study phase (main efficacy parameter) 30 Anzahl Schmerztage No. of days with headache 20 10 0 -10 N = Study phase Studienphase 95 95 95 95 95 A1 B1 C1 B2 A2 The box shows medians to the 25th and 75th percentiles. In addition, the major distribution range (bars) up to extreme and outlying values (asterisk, circles) is given. The main results according to pain diaries The parameters shown are those for which the Friedmann test for case-related change was significant or borderline significant. Results for the whole group analysed Parameters according to headache diary Baseline (median) Change per participant* Follow-up (median) Median for differences in the parameters per participant (follow-up minus baseline) We can see clear indications of improvements in the pain situation, not only from the change in the number of days with pain but also in the number of pain attacks and in pain intensity, Number of days with headache days days 1 day per 28 days related to the entire collective and also8 related to changes5 per participant.-In the case of the relative to 28 days (main efficacy parameter) Marburg questionnaire on habitual well-being and also in subjective evaluation of impairment No. of headache attacks 6.7 attacks 4.2 attacks -1.9 attacks (PDI), this tendency even reaches the 75th percentile (not shown in the table). relative to 28 days per 28 days No changes were registered for the duration of pain attacks, there was even a (statistically Mean pain intensity per attack 3.5 (VAS) 3.1 (VAS) - 0.3 (VAS) irrelevant) according increase. to diary Correlation between exercises and results Period of headache per attack 13.1 hours 13.3 hours +1.1 hours According relative toto 28the daysparticipants themselves, 80 out of 95 kept up individual exercises between “several times per week” to “daily” at the beginning of the repetition stage. 75 persons gave Period of headache per day with 12.0 hours 12.8 hours +0.4 hours the headache durationrelative of training as between “10 minutes” , “15 minutes” and “20 minutes and more”. to 28 days The large majority had therefore exercised several times per week for at least 10 minutes. * Negative values show a reduction, positive ones show an increase. 8 The main results from the questionnaires The parameters shown are those for which the Friedmann test for case-related change was significant or borderline significant. Parameters in questionnaire Start of baseline (median) End of follow-up (median) Median for differences in parameters per participant* (follow-up minus baseline) Pain intensity according to data in questionnaire 7.05 (VAS) 4.45 (VAS) -2.30 Imaginable bearable pain intensity according to data given in questionnaire 2.10 (VAS) 2.15 (VAS) +2.50 Habitual well-being (Marburg questionnaire**) 3.71 4.66 +0.72 Pain Disability Index (PDI) 38.50 24.00 -13.50 * Negative values show a reduction, positive ones show an increase. ** Marburger Fragebogen zum habituellen Wohlbefinden Only one test person (two at the end of the study) indicated they did not exercise. 14 persons exercised once per week. A control group of persons without exercises did not form. At this level, no correlation was found between different intensity and different changes in target sizes. The reason, although this may seem illogical, is the high degree of compliance among participants. It must be pointed out in this context that this fact would not have made a randomization possible, e.g. with a waiting list as suggested, since the clients of this study were interested in active therapy. Subsequent evaluation with 21 participants One year after the study started, those 32 participants received a written request who were the first test persons at the end of 2000, i.e. a random selection. They were asked to keep a journal once again for one month and to fill in a questionnaire. 25 of them answered. 21 persons indicated that they exercised regularly, 19 at least several times per week for different periods. These persons did not show any changes compared to follow-up with regard to significant target sizes in the median of case-related evaluations. Discussion An evaluation of results may be summarized as follows: Changes in primary efficacy measure and significant secondary efficacy measures are statistically significant. Changes are characterized by a continuous development towards improvement not only of the main target size but also of several significant target sizes. The overall result may therefore be considered as stable. The fact that participants exercised consistantly, regularly and independently at an early point in the study and also subsequently is a further indication that the therapy under consideration meets with acceptance. The continuously favorable results in follow-up suggest that the method is efficient for individual training. A possible objection is that it cannot be verified whether participants registered their pain experience and their exercise behaviour correctly. This objection cannot be dismissed completely since nobody had the intention nor the opportunity to check on the test persons. But even in drug studies where patients take part under real conditions there remains uncertainty whether test persons actually take drugs whenever they record an intake. In this study, the 9 mainly similar statements on exercise behaviour as well as on pain intensity gathered from questionnaires and journals appear to indicate that what patients recorded corresponded to what they did and felt. Assessment of responder rate according to drug studies criteria The 1991 version and the second version of 2000 of the “Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine”, and also the guidelines for research into drug efficacy in tension-type headache medication recommend to measure the efficiency of a prophylactic drug by the “percentage of persons with a reduction in days with pain by 50 % and more”3, or by the number of days with pain respectively. (3 “The number of responders can be expressed as those with a more than 50 % reduction in attack frequency during treatment period compared with baseline period” (International Headache Society Committee on Clinical Trials in Migraine, first edition, 1991, p.10); “Responder rate is defined as the percentage of subjects in a treatment group with 50 % or greater reduction in attack frequency during treatment, compared with baseline” (International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee, second edition, 2000, p. 778).) 27 out of 95, i.e. 28 % of evaluable participants in this study showed a reduction in days with pain by more than 50 %. Grouped according to number of days with pain in baseline, 12 persons (30 %) in the group with 3-7 days with pain (N=40) had a reduction of at least 50 % in follow-up; in the group with 8-14 days with pain in baseline (N=32) there were 11 persons (34 %) with a reduction of at least 50 % in follow-up. These two groups taken together, i.e. 72 test persons, make up for 75 % of participants and are therefore statistically relevant. Another measure is the reduction in per cent of the collective number of days with pain. The reduction in the number of days with pain was 20 % for all subjects. The two middle groups again hat the highest percentage of participants with a reduction: in the group with 3-7 days with pain (N=40) in baseline, the reduction per cent of the number of days with pain was 25 % in follow-up, in the group with 8-14 days with pain in baseline (N=32), the reduction of days with pain was 31 % in follow-up. Van der Kuy and Lohmann (2002) performed a meta analysis with 22 double-blind and placebo-controlled studies into effects of 19 drugs for migraine prophylaxis. They suggest that further studies into prophylactic drugs make sense if previous studies have shown responder rates of more than 35-40 % or have demonstrated a reduction in attack frequency by 40 %.4 (4 “If the percentage of responders in an open-label prophylactic trial in migraine is above 35-40%, or if a reduction in migraine attack frequency of 40 % or more is observed, further studies are indicated” (van der Kuy and Lohmann 2002, p. 269).) Guidelines for research into tension-type headache therapy also mention a generally high placebo rate of between 20 and 40 % for migraine prophylactics.5 (5 “The placebo effect in migraine prophylaxis is usually in the range 20-40%, and there is no reason to believe that this is any different in chronic TH” (Guidelines for trials of drug treatments in tension-type headache, first edition, Cephalalgia 1995, 15: 172).) Compared to these definitions, the results of this study are in the placebo range. The “Placebo” concept in research of drug-free therapies Obviously, new prophylactic drug therapies have to show a therapy success that goes beyond a supposedly high placebo effect. Possible side effects or contraindications of prophylactic drugs have to be taken into account. The serious application of Qigong exercises, however, will not involve any contraindications, except in very rare cases. In addition, Qigong exercises may also be applied as elements of an integrative treatment concept, similar to other drug-free headache therapies, and like other therapies involving exercises may also be included in multimode concepts (Lake 2001). Therefore they are not used in competition with established therapies, to be judged according to the same criteria for success. Qigong exercises may also be an alternative for persons with contraindications or a distrust of prophylactic drugs. Only 13 subjects in this study received prophylactic medication. 10 Nor do international recommendations prescribe the often quoted success indicator of a high percentage of persons with a reduction over 50% and more in days with headache or migraine attack frequency for drug studies.6 (6 “The choice of 50 % or greater reduction is traditional and arbitrary, and the investigator (or patient) should be the judge of what is considered a good response” (International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee, second edition, 2000, p. 778). ”The choice of a quantal measure of effect of more than 50% reduction is traditional and arbitrary, and the investigator should be the judge of what should be considered a good response” (Guidelines for trials of drug treatments in tension-type headache, first edition, Cephalalgia 1995, 15: 172).) The International Headache Society in its revised recommendations for migraine studies underlines the significance of designing parameters that refer to an assessment of life quality (health-related quality of life, HRQOL).7 (7 “End-points currently used in migraine trials are statistically powerful but almost certainly do not well reflect patients’ values”: International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcomittee, second edition, 2000, p. 779-80.) The improvement of parameters in this study on quality of life up to the 75th percentile (PDI and Marburg questionnaire on habitual well-being) may be considered extremely positive in this sense. Various statements by patients on pain experience may be evaluated not from a statistical but rather a qualitative perspective; two of these are quoted as follows: “In general, I wish to add that the exercises have not only had a positive influence on my headaches; falling asleep has become far easier for me. Before, it took me often up to one hour to fall asleep, now only ca. 10 minutes.” “Qigong not only had a positive effect on the headaches, it also generally gave me more zest for life. Qigong helped me work off everyday stress better, so it helped release energies that would otherwise have been bottled up.” Against the background of these considerations, the reduction in the main traget size is a less important criterion compared to a therapy involving drugs. Qigong and blind studies Blind tests are possible and desirable in the evaluation of most treatments; however, they are not possible in research on the effects of Qigong exercises: therapists and patients both should know exactly what they do. In contrast to a neutral attitude towards therapy, what we expect here is an active participation of test persons, and perhaps even positive hopes and enjoyment of therapy; this corresponds to the literal translation of “placebo”. A team of scientists from St. Louis (Kalauokalani et al. 2001, 1418-1424.2001) presented a randomized study with 135 back pain patients in the journal Spine and described the influence of expectations for the specific therapy type – acupuncture versus massage – on an improvement of complaints after treatment. Prior to randomization, patients were interviewed on their expectations for the efficiency of the therapy type to be applied in their case. 86 % of patients with high expectations for their specific therapy type registered an improvement in complaints after treatment. Among those who expected little help from treatment, 68% recorded an improvement (p=0.01). Consequently, the authors of this study demand that the test persons’ expectations for their specific therapy type be included in research in all studies on the efficiency of particular therapy forms where blind tests are not possible. This suggestion should be included in further studies. Conclusions and hypotheses The description of methods used in the pilot study presented here explained that the objective was hypothesis generation versus validation of the method explored. Several hypotheses may be formulated as a result of the study: Mainly middle-aged women would choose Yangsheng exercises as a form of treatment. Regular independent exercising even at an early time point in the course of the study suggests acceptance of the treatment being investigated. 11 The observed reduction in the number of days with headache per study phase and other important subsidiary target values indicate that Yangsheng exercises are an effective treatment. The main area of efficiency is prophylaxis. No reduction in the period of the individual headache attacks can be expected. The increase in habitual well-being and the reduction in the subjective handicap assessment indicate improved pain management. Further studies to confirm these findings would be useful, although the randomization process (e.g. “waiting list”) is likely to involve acceptance problems. Further studies, even randomized studies, are indicated. The findings of this study might be helpful; some changes might be introduced, e.g. a shorter duration of the entire study, or a reduction in secondary target sizes. Phase III studies that compare one method with another usually pose the question: “Which is better?” But in research it should also be legitimate to ask: “Which might be better for whom?” Studies into drug-free therapies might provide valuable stimuli for medical research. Definitions and notes on some abbreviations and terms Boxplot according to Tukey (1970): A method to present frequency distribution in a graph. The box contains median, 25th to 75th quartile. The (beam?) goes from 25% quartile minus 1.5fold interquartile distance I to 75% quartile + 1.5fold interquartile distance. In addition, stray values are presented (circles) between end of (beam?) and 25% quartile minus three-fold interquartile distance I , resp. 75% quartile plus three-fold interquartile distance I and extreme value (asterisk) outside the stray range. Median: also central value. The median “is located in the middle of all values observed. It is exceeded by half of the values at most, and half of the values at most are below the median” (Harms 1998, p.25) P-value: “The p-value is often described as transgression probability since it indicates the probability with which according to the null hypothesis (i.e. the hypothesis that the study has not found any effect, E.F.) the results found or even extremer results will occur.” (Harms, 1998, p. 200). The p-value calculated from statistical rules is therefore a measure for error probability. Values below 0.05 (percent) are considered statistically significant according to international standards. The study was supported by the German Medical Acupuncture Association (DÄGfA) and the German Medical Association for Qigong Yangsheng. Comprehensive statistical counseling and calculations were realized by Dr. rer.nat. Beate Pfister. Contact: Dr. Elisabeth Friedrichs, Seefelder Str. 27, D-86163 Augsburg, Germany, E-mail: elfriedaug@aol.com. References Aitken RCB. Measurement of feelings using visual analogue scales. Proc Roy Soc B, 1969, 62: 17-24. Aldridge D. Single-case-research designs for the clinician. J Roy Soc Med, 1991, 84 (May): 249-252. Aldridge D. The Needs of Individual Patients in Clinical Research. Advances, The Journal of Mind-Body Health, 1992, 8 (4): 5865. Bantick SJ, Wise RG, Ploghaus A, Clare S, Smith SM, Tracey I. Imaging how attention modulates pain in humans using functional MRI. Brain, 2002, 125: 310-319. Basler HD. Marburger Fragebogen zum habituellen Wohlbefinden. Untersuchungen an Patienten mit chronischem Schmerz. Der Schmerz, 1999, 13 (6): 385-391. 12 Blanchard EB, Appelbaum KA Nicholson NL, Radnitz CL, Morrill B, Michultka D, Kirsch C, Hillhouse J, Dentinger MP. A Controlled Evaluation of the Addition of Cognitive Therapy to a Home-Based Biofeedback and Relaxation Treatment of Vascular Headache. Headache, May 1990: 371-375. Brown JM. Imagery Coping Strategies in the Treatment of Migraine. Pain, 1984, 18: 157-166. Brüggemann W (Hrsg.). Kneipp-Therapie: ein bewährtes Naturheilverfahren. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2. Auflage 1986. Carlsson J, Fahlcrantz A, Augustinsson LE. Muscle tenderness in tension headache treated with acupuncture or physiotherapy. Cephalalgia 1990, 10: 131-141. Cobos-Schlicht C. Der Berg ist Mensch, der Mensch ist Berg. Aus den Lehren des daoistischen Alchimisten Gě Hóng (283-363). Zeitschrift für Qigong Yangsheng, 2002: 65-90. Daly EJ, Donn PA, Galliher MJ, Zimmerman JS. Biofeedback Applications to Migraine and Tension Headaches: A DoubleBlinded Outcome Study. Biofeedback and Self-Regulation, 1983, 8 (1): 135-152. Darling M. Exercise and migraine, a critical review. The Journal Of Sports Medicine And Physical Fitness, 1991, 31 (2): 294299. Despeux C. Das Mark des Roten Phönix, Unsterblichkeit, Gesundheit und langes Leben in China. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 1995. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Biofeedback e.V. "Information", zitiert nach www.bio-feedback.de (gefunden 6. Mai 2002). Di Biasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. The Lancet, 2001, 357: 757-762. Diener HC, Brune K, Gerber WD, Pfaffenrath V, Straube A. Therapie der Migräneattacke und Migräneprophylaxe – Empfehlungen der Deutschen Migräne- und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (DMKG). Nervenheilkunde, 2000, 6: 69-79. Diener HC. Akuttherapie und Prophylaxe der Migräne. MMW-Fortschr.Med., 2002, 3-4: I-X. Diener HC. Medication Overuse. Cephalalgia, 2001, 21: 278. Diener HC. Migräne. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1999a. Dillmann U, Nilges P, Saile H, Gerbershagen HU. Behinderungseinschätzung bei chronischen Schmerzpatienten. Der Schmerz, 1994, 8: 100-110. Edmeads J, Mackell JA. The economic impact of migraine: an analysis of direct and indirect costs. Headache 2002, 42 (6): 501-9. Engelhardt U. Die Behandlung bestimmter Krankheitsbilder mit Yangsheng-Methoden – Eine Untersuchung anhand des Zhubing yuanhou lun ("Abhandlung über Ursprung und Verlauf sämtlicher Krankheiten") aus dem 7. Jahrhundert. In: Hildenbrand G, Geißler M (Hrsg.) 2002, S. 33-38. Engelhardt U. Die klassische Tradition der Qi-Übungen (Qigong): eine Darstellung anhand des tangzeitlichen Textes Fuqi Jingyi Lun von Sima Chengzen. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 2. Auflage 1997, zugl.: München, Univ.-Diss., 1985. Ethical issues in headache research and management: report and recommendations of the ethics subcommittee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia, 1998, 18: 505-529. Evers S, Gralow I, Bauer B, Suhr B, Buchheister A, Husstedt IW, Ringelstein EB. Sumatriptan and ergotamine overuse and drug-induced headache: a clinicoepidemiologic study. Clin Neuropharmacol, 1999, 22: 201-206. Fichtel A, Larsson B. Does relaxation treatment have differential effects on migraine and tension-type headache in adolescents? Headache, 2001, 41: 290-296. Flor H. Chronic pain and headache: a biobehavioural perspective. Cephalalgia, 2001, 21: 241. Flor H. The functional organization of the brain in chronic pain. In: Sandkühler J, Bromm B, Gebhart GF (Eds.), Progress in Brain Research, Elsevier Science, 2000, 129: 313-322. Flöter T, Müller-Schwefe G, Seemann H, Topp F. Schmerzfragebogen des Schmerztherapeutischen Kolloquiums e.V., zu beziehen über Schmerztherapeutisches Kolloquium e.V, Adenauerallee 18, 61440 Oberursel. email: stk.zentrale@stk-ev.de, 1998. Frankenberg SV, Pothmann R, Hoicke C, Thoiss W. Nutritional treatment of Children with migraine and tension-type headache: a controlled research-study of 117 children. Cephalalgia, 2001, 21: 463. Friedrichs E.Qigong-Yangsheng-Übungen in der Begleitbehandlung bei Migräne und Spannungskopfschmerz: Ergebnisse einer multizentrischen prospektiven Pilotstudie. Zeitschrift für Qigong Yangsheng, 2003, 101-112. Geisser ME, Roth RR, Robinson ME. Assessing Depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory, A comparative Analysis. The clinical Journal of pain, 1997, 13: 163-170. Gerber WD, Kropp P, Siniatchkin M. "Born to be wild or learned?" A new biobehavioural hypothesis of the etio-pathogenesis of migraine. Cephalalgia, 2001, 21: 241. Gerber WD, Miltner W, Gabler H, Hildenbrand E, Larbig W. Bewegungs- und Sporttherapie bei chronischen Kopfschmerzen. In: Gerber WD, Miltner W, Mayer K (Hrsg.). Verhaltensmedizin: Ergebnisse und Perspektiven interdisziplinärer Forschung. Weinheim: Edition Medizin, 1987, S. 55-66. Gerber WD. Kopfschmerz und Migräne – Ursachen erkennen, Schmerzen überwinden – Das 10-Schritte-Programm zur Selbsthilfe. München: Mosaik, 1998. Ghubash R, Daradkeh TK, AI Naseri KS, AI Bloushi NB, AI Daheri AM. The performance of the Center for Epidemiological Study Depression Scale (CES-D) in an Arab female community. Int J Soc Psychiatry, 2000 Winter, 46 (4): 241-9. Goadsby PJ. Pathophysiology of Migraine. Cephalalgia, 2001, 21: 250. Goadsby PJ. Migraine pathophysiology: the brainstem governs the cortex. Cephalalgia, 2003, 23: 565-66. Göbel H, Buschmann P, Heinze A, Heinze-Kuhn K. Epidemiologie und sozioökonomische Konsequenzen von Migräne und Kopfschmerzerkrankungen. Versicherungsmedizin, 2000, 52 (1). Göbel H, Einhäupl KM, Offenhauser N, Lipton R.B. Spezialextrakt aus Petasitesrhizom ist wirksam in der Migräneprophylaxe: Eine randomisierte, multizentrische, doppelblinde, placebokontrollierte Parallelgruppenstudie. Der Schmerz 2001, 15, Supplement 1: 61, 2001. Göbel H, Heinze A, Heinze-Kuhn K. Die Attacke abwehren, dem Kopfschmerz vorbeugen, Migränetherapie im Jahre 2002. MMW-Fortschr. Med., Sonderheft 2/2002: 43-50. Göbel H. Kopfschmerzen und Migräne: Leiden, die man nicht hinnehmen muß. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2. Aufl. 1998. Göbel H, Petersen-Braun M, Soyka D. The epidemiology of headache in Germany: a nationwide survey of a representative sample in the basis of the headache classification of the international Headache Society. Cephalalgia, 1994, 14: 97-106. Göbel H, Soyka D, Ziegler A, Diener HC. Selbstmedikation bei Migräne und Kopfschmerz vom Spannungstyp: Empfehlungen der Deutschen Migräne- und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft. Deutsche Apothekerzeitung, 1995, 135 (9): 763-778. Grazzi L, Andrasik F, D'Amico D, Leone M, Usai S, Kass SJ, Busson G. Behavioral and pharmacological treatment of transformed migraine with analgetic overuse: outcome at 3 years. Headache, 2002, 42 (6) 483-90. Grönblad M, Hurri H, Kouri JP. Relationships between spinal mobility, physical performance tests, pain intensitiy and disability assessments in chronic low back pain patients. Scan J Rehab Med 29: 1997, 17-24. 13 Grossmann M, Schmidramsl H. An extract of Petasites hybridus is effective in the prophylaxis of migraine. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics, 2000, 38 (9): 430-435. Haag G, Evers S, May A, Neu IS, Vivell W, Ziegler A. Evidenz-basierte Empfehlungen der Deutschen Migräne- und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft (DMKG) zur Selbstmedikation bei Migräne und Kopfschmerz vom Spannungstyp. www.dmkg.de/thera/selbst.htm, gefunden am 03.03.2003. Harms V. Biomathematik, Statistik und Dokumentation: eine leichtverständliche Einführung; nach den Gegenstandskatalogen für den 1. und 2. Abschnitt der ärztlichen Prüfung, Kiel-Mönckeberg: Harms, 1998. Hay KM, Madders J. Migraine treated by relaxation therapy. J Roy Coll gen Practit, 1971, 21: 664-669. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society: Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgies and facial pain. Cephalalgia, 1988, Suppl 7: 1-98. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society: The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd Edition, Cephalalgia, 2004, Suppl 1: 1-160. Heine H. Akupunktur, Schmerz und Grundsystem. In: Pothmann 1996, S. 15-20. Hempen CH. dtv-Atlas zur Akupunktur. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, 1995. Hess R, Krimmel L (Bearb.). Gebührenordnung für Ärzte (GOÄ). Deutscher Ärzteverlag Köln, 1996, S. 84. Hildenbrand G. Qigong Yangsheng: Das Gute stützen – das Schlechte vertreiben. In: R. Pothmann, 1996, S. 145-157. Hildenbrand G, Geißler M (Hrsg.). Qigong und Yangsheng: Vorträge der 4. Deutschen Qigong-Tage Bonn, Von den Wurzeln in Daoismus und Heilkunde bis zur heutigen Anwendung. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 2002. Hildenbrand G, Geißler M, Stein S (Hrsg.). Das Qi kultivieren, die Lebenskraft nähren, West-Östliche Perspektiven zu Theorie und Praxis des Qigong und Yangsheng. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl-Ges., 1998a. Hildenbrand G, Kahl J, Stein S. Qigong und China, Institut für Internationale Zusammenarbeit des Deutschen Volkshochschulverbandes e.V. (IIZ/DVV). Bonn IIZ/DVV 1998b. Hoodin F, Brines BJ, Lake AE III, Wilson J, Saper JR. Behavioral Self-Management in an Inpatient Headache Treatment Unit: Increasing Adherence and Relationship to Changes in Affective Distress. Headache, May 2000, S. 377-380. International Headache Society Clinical Trials Subcommittee. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine. Second edition. Cephalalgia, 2000, 20: 765-786. International Headache Society Committee on Clinical Trials. Guidelines for trials of drug treatments in tension-type headache. First edition. Cephalalgia, 1995, 15: 165-179. International Headache Society Committee on Clinical Trials in Migraine. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine. First edition. Cephalalgia, 1991, 11: 1-12. International Headache Society Committee on Clinical Trials in Migraine. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine. First edition. The IHS Members' Handbook 2000, 111-133. Jacobsen E. Progressive relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1938. Jiao Guorui. Das Spiel der fünf Tiere. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 1992. Jiao Guorui. Die 15 Ausdrucksformen des Taiji-Qigong. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 6. Auflage 2001. Jiao Guorui. Die Theorie der 5 Wandlungsphasen und ihre Beziehung zum Spiel der 5 Tiere des medizinischen Qigong. In: Qigong Yangsheng, Übungen der traditionellen chinesischen Medizin, Jahresheft 1994, Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., S. 20 – 30. Jiao Guorui. Qigong Yangsheng, ein Lehrgedicht. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 1993. Jiao Guorui. Qigong Essentials for Health Promotion. Beijing: China Today Press, 2nd ed.1990. Jiao Guorui. Qigong Yangsheng: Chinesische Übungen zur Stärkung der Lebenskraft. Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer-Taschenbuch, 1996. Jiao Guorui. Qigong Yangsheng: Gesundheitsfördernde Übungen der Traditionellen Chinesischen Medizin. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 2. Auflage 1989. Kalauokalani D, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Koepsell TD, Deyo RA. Lessons from a trial of acupuncture and massage for low back pain: patient expectations and treatment effects. Spine, 2001, 26: 1418-1424. Kampik G. Propädeutik der Akupunktur. Stuttgart: Hippokrates, 1997. Kaptchuk TJ. Das große Buch der chinesischen Medizin. Wien: Otto Wilhelm Barth, 2. Sonderauflage 1991. Kaptchuk TJ. The Web That Has No Weaver: Understanding Chinese Medicine. Chicago: Congdon and Weed, 1983. Kaube H, May A, Diener HC, Pfaffenrath V. Sumatriptan misuse in daily chronic headache. BMJ, 1994, 308: 1573. Kopfschmerz-Klassifikations-Komitee der International Headache Society. Klassifikation und diagnostische Kriterien für Kopfschmerzerkrankungen, Kopfneuralgien und Gesichtsschmerz. Nervenheilkunde, 1989, 8 (4): 161-203. Kropp P, Gerber WD. Contingent negative variation during migraine attack and interval: evidence for normalization of slow cortical potentials during the attack. Cephalalgia, 1995, 15: 123-8. Lake AE III. Behavioral and nonpharmacologic treatments of Headache, Medical Clinics of North America, 2001, 85 (4): 10551075. Larbig W. Progressive Muskelentspannung, Ruhe als Heilmittel. Der Allgemeinarzt 18-2002, S. 1388-1395. Limmroth V, Diener HC. Kopfschmerzen – Neues zu Pathophysiologie und Therapie der Migräne. Notfallmedizin 2003, 29: 3241. Linde K. Systematische Übersichtsarbeiten und Metaanalysen – Anwendungsbeispiele und empirisch-methodische Untersuchungen. http://dochost.rz.hu-berlin.de/habilitationen/linde-klaus-2002-12-03/PDF/Linde.pdf. Lurie JD. Point of View. Spine, 2001, 26: 1424. Maoshing Ni. The Yellow Emperor‘s Classic Of Medicine; A new translation of the Neijing Suwen with commentary. 1 st ed. Boston and London, 1995. Marcus DA, Scharff L, Mercer S, Turk DC. Nonpharmacological treatment for migraine: incremental utility of physical therapy with relaxation and thermal biofeedback. Cephalalgia, 1998, 18: 266-272. Massiou H, Tzourio C, el Amrani M, Bousser MG. Verbal scales in the acute treatment of migraine: semantic categories and clinical relevance. Cephalalgia 1997, 17: 37-39. McCrory DC, Penzien DB, Gray RN, Hasselblad V. Efficacy of behavioural and physical treatments for tension-type headache and cervicogenic headache: meta-analysis of controlled trials. Cephalalgia, 2001, 21 (4): 283. Melchart D, Linde K, Fischer P, White A, Allais G, Vickers A, Berman B. Acupuncture for recurrent headaches: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cephalalgia, 1999, 19: 779-786. Melchart D, Linde K, Weidenhammer W, Streng A, Reitmayr S. Patient Care Evaluation Program for Acupuncture (PEPAC). FACT, 2002, 7: 100. Molsberger A, Diener HC, Krämer J, Michaelis J, Schäfer H, Trampisch HJ, Victor N, Zenz M. GERAC-Akupunktur-Studien – Modellvorhaben zur Beurteilung der Wirksamkeit. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 2002, 99 (26): A 1819-1822. 14 National Institute of Mental Health – Division for Scientific and Public Information – Plain Talk Series – Ruth Kay, Editor, What is Biofeedback? Zitiert nach www.psychotherapy.com/bio.html (gefunden 6. Mai 2002). Neuer BDA-Leitfaden: Diagnostik und Therapie der Migräne in der Hausarztpraxis. Der Hausarzt, 2002, 39 (1), Beilage. Niederberger U, Weinschütz T, Gerber WD. Methoden der klinischen Kopfschmerzforschung zur Evaluation der Akupunktur: Migräne- und Kopfschmerz-Tagebücher. Aku 1997, 25 (3): 190-97. Noble-Topham SE, Dyment DA, Cader MZ, Ganapathy R, Brown J, Rice GP, Ebers GC. Migraine with aura is not linked to the FHM gene CACNA1 or the chromosomal region, 19p13. Neurology, 2002, 59 (7): 1099-1101. Ohnhaus EE, Adler R. Methodological Problems in the Measurement of Pain: A comparison between the verbal rating scale and the visual analogue scale. Pain, 1975, 1: 379-384. Olesen J. Revision of the International Headache Classification. An interim report. Cephalalgia, 2001, 21: 261. Olesen J. ICHD-II: the new IHS classification of headaches. Cephalalgia, 2003, 23: 567. Ots T. Medizin und Heilung in China – Annäherungen an die traditionelle chinesische Medizin. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1990. Pfaffenrath V, Brune K, Diener HC, Gerber WD, Göbel H. Die Behandlung des Kopfschmerzes vom Spannungstyp – Therapieempfehlungen der Deutschen Migräne- und Kopfschmerzgesellschaft. Nervenheilkunde, 1998, 17: 91–100. Pfaffenrath V, Diener HC, Isler H, Meyer C, Scholz E, Taneri Z, Wessely P, Zaiser-Kaschel H, Haase W, Fischer W. Efficacy and tolerability of amitriptylinoxide in the treatment of chronic tension-type headache: a multi-centre controlled study. Cephalalgia, 1994, 14: 149-155. Pollard, CA. Preliminary validity study of the Pain Disability Index. Percept Mot Skills, 1984, 59: 974. Pothmann R (Hrsg.). Systematik der Schmerzakupunktur. Stuttgart: Hippokrates, 1996. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Measurement, 1977, 1: 385-401. Reuther I. Qigong Yangsheng als komplementäre Therapie bei Asthma. Frankfurt a.M.: Hänsel-Hohenhausen, 1997. Reuther I. Über Spezifität und Ganzheitlichkeit von Qigong-Übungen. Zeitschrift für Qigong Yangsheng, 2001: 79-85. Risch M, Scherg H, Verres R. Musiktherapie bei chronischen Kopfschmerzen, Evaluation musiktherapeutischer Gruppen für Kopfschmerzpatienten. Der Schmerz, 2001, 2: 116-125. Ritter Ch. Qigong Yangsheng als Therapieansatz bei essentieller Hypertonie im Vergleich zu einer westlichen Entspannungstherapie. Frankfurt a.M.: Hänsel-Hohenhausen, 2000. Robson C. Real world research: a resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. Malden, USA, Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2nd edition 2002. Ross J. Zang Fu, Organsysteme der Chinesischen Medizin. Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., 2. Auflage, 1995. Ryu H, Lee HS, Shin YS, Chung SM, Lee MS, Kim HM, Chung HT. Acute effect of Qigong Training on Stress Hormonal Levels in Man. American Journal of Chinese Medicine, 1996, 24 (2): 193-198. Sandleben WI, Schläpfer R. Die Wirkung von Qigong Yangsheng nach kurzer Übungspraxis – Befragungsergebnisse aus 44 Qigong-Yangsheng-Kursen. Zeitschrift für Qigong Yangsheng 1997, Uelzen: Med.-Lit. Verl.-Ges., S. 109. Santé, Préventions santé: Certains aliments agissent comme déclencheurs. Fundstelle www.canoe.qc.ca/ArtdevivreSante/Sept6-migraine_2html, 15.11.2002 Schmidt K. Teure Migränepatienten: Regressrisiko oder Chance für die Praxis? MMW-Fortschr.Med. 15, 2003 (145. Jg), S. 6061. Schwarz JA. Leitfaden Klinische Prüfungen von Arzneimitteln und Medizinprodukten. Aulendorf: Editio-Cantor, 2. Aufl. 2000. Sheehan TJ, Fifield J, Reisine S, Tennen H. The Measurement Structure of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Journal of Personal Assessment, 1995, 64 (3): 507-521. Sorbi M, Tellegen B, Du Long A. Long-Term Effects of Training in Relaxation and Stress-Coping in Patients with Migraine: A 3year Follow-Up. Headache, January 1989: 111-120. Sorbi M, Tellegen B. Differential Effects of Training in Relaxation and Stress-Coping in Patients with Migraine. Headache, October 1986: 473-480. Staib AH. Die Phasen der Klinischen Prüfung, Arzneimittelprüfung und good clinical practice: Planung, Durchführung und Qualitätssicherung. MMV 1994: 96. Stein S. Zwischen Heil und Heilung – zur frühen Tradition des Yangsheng in China. Uelzen: Med.- Lit. Verl.-ges., 1999, zugl.: Bonn, Univ.-Diss., 1998. Steiner TJ, Findley LJ, Yuen AWC. Lamotrigine versus placebo in the prophylaxis of migraine with and without aura. Cephalalgia, 1997, 17: 109-112. Steiner TJ, Joseph R, C. Hedman C. Rose, FC. Metoprolol in the prophylaxis of migraine: parallel-groups comparison with placebo and dose-ranging follow-up. Headache 1988: 28: 15-23. Tukey JW. Exploratory Data Analysis: Limited Preliminary Ed. Addison-Wesley Publishing. Reading, MA, 1970. Unschuld PU. Chinesische Medizin. Beck‘sche Reihe, München: C.H. Beck, 1997. van der Kuy PH, Lohman JJHM. A quantification of the placebo response in migraine prophylaxis. Cephalalgia, 2002, 22 (4): 265-270. Warner G, Lance JW. Relaxation Therapy in Migraine and Chronic Tension Headache. The Medical Journal of Australia, March 8, 1975: 298-301. Weidenhammer W, Streng A, Reitmayr S, Hoppe A, Linde K, Melchart D. Das Modellvorhaben Akupunktur der Ersatzkassen. Ein Zwischenbericht zu den Ergebnissen der Beobachtungsstudie. Dt Zschr F Akup, 2002, 45: 183-192. Zenz M, Jurna I (Hrsg.). Lehrbuch der Schmerztherapie. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 2. Auflage 2001. Zimmer Ch, Basler HD. Schulungsprogramm "Schmerz im Gespräch", Stadien der Chronifizierung und Effekte der Schulung. Der Schmerz, 1997, 11 (5): 328-336. 15