dpb 2014 CLCC Conservation Easement Outline

Conservation Easements: What They Are, Pros & Cons

Daniel P. Brown, Jr.

Granby Land Trust

1.

A conservation easement can be a deeply satisfying opportunity for a landowner to protect a cherished parcel of land. It is:

a transfer of some, but not all, rights in a parcel of land , with the result that the landowner continues to own the property, but the land trust has rights to prevent certain activities (the building of a house, for instance) on the property as detailed in the deed by which the conservation easement is granted (Being essentially a contractual arrangement, a conservation easement differs from a fee interest, i.e. full ownership of the property);

both a deed that conveys certain property rights to the land trust and a binding contract between the landowner and the land trust;

an arrangement that creates a land trust’s ongoing stewardship responsibility and, potentially, a future financial liability if the easement is violated and the land trust is forced to bring a legal action to enforce its rights; and

if the donor seeks a tax deduction, a purchase of the property’s conservation values by the federal government . After all, the landowner’s tax deduction is, in effect, an indirect governmental subsidy, because the landowner is economically advantaged by the transaction. In this sense, the land trust has been deputized to act as the government’s purchasing agent.

2.

Usually, a conservation easement is acquired in one of three ways: (i) as the landowner’s tax deductible gift ; (ii) as a purchase by the land trust , either at the conservation easement’s appraised full fair market value or in a “bargain sale” transaction; or (iii) as a “ quid pro quo” set-aside required by a planning and zoning commission in connection with the development of an adjacent parcel. “ Bargain sales

” are just what the name implies, sales at less than full market value, with the seller’s discount being treated as a tax-deductible gift.

“

Quid pro quo

” transactions are not tax-deductible, since the landowner is receiving back the benefit of subdividing his or her other parcel.

3.

Tax-deductible gifts: Section 170(h) of the Internal Revenue Code provides that a taxpayer may claim a deduction for the transfer of a “qualified conservation contribution ,” which it defines as being (i) a contribution of a

“ qualified real property interest ,” (ii) to a “ qualified organization ,” (iii)

“ exclusively for conservation purposes

.”

A “ qualified real property interest ” can be “a restriction (granted in perpetuity) on the use which may be made of the real property.” This is what a conservation easement is.

A land trust is, or should be, a “ qualified organization ” if it is a 501(c)(3) charity.

“

Conservation purpose means:

(i) the preservation of land areas for outdoor recreation by, or the education of, the general public,

(ii) the protection of a relatively natural habitat of fish, wildlife, or plants, or similar ecosystem,

(iii) the preservation of open space (including farmland and forest land) where such preservation is –

(I) for the scenic enjoyment of the general public, or

(II) pursuant to a clearly delineated Federal, State, or local governmental conservation policy , and will yield a significant public benefit , or

(iv) the preservation of an [sic] historically important land area

. . . .”

4.

When considering whether to solicit or accept a gift of a conservation easement, a land trust should consider these questions:

Does the gift achieve a “conservation purpose” as defined in Section

170(h)? Simply preventing development on the land is not enough.

How does the acquisition further the land trust’s goals?

Is the land otherwise developable or at risk? If not, why should the land trust be involved at all?

Is the land trust the property’s best steward? Should another charity or perhaps even a homeowner’s association accept the gift?

Will the restriction be “perpetual”?

Does the land trust have the resources, the personnel and the willingness to monitor and, if necessary, enforce the easement now and in the future?

Are the restrictions described in the easement understandable and enforceable? If it includes a “no hunting” restriction, for instance, does that make sense and how could the land trust enforce it?

Does the land trust believe that the landowner’s anticipated tax deduction will be a proper one?

2

Has the land trust advised the landowner of the land trust’s closing requirements?

Are the landowner and the land trust each represented by knowledgeable counsel?

Is the landowner’s appraiser a “qualified appraiser” who meets IRS requirements? Search for “qualified appraiser” at www.IRS.gov

.

Is the property surveyed, or will it be, and are boundaries properly pinned?

5.

In broad outline, most conservation easements follow a similar format.

The document is structured somewhat like a deed and begins with the identification of the parties.

The conservation purposes are described in considerable detail.

The restrictions imposed on the landowner are described.

The landowner’s reserved rights are described.

Miscellaneous mutually agreed upon provisions are detailed. These often include the land trust’s right to sue to enforce the easement and how the costs of litigation are to be paid.

The final pages include signature lines for the landowner, the land trust and witnesses, as well places for the notaries to sign and a legal description of the property to be encumbered by the easement.

6.

In order to secure a tax deduction, the land owner must provide:

a correctly drafted conservation easement,

IRS Form 8283 and the supplemental statement required by the instructions to that form,

a “qualified appraisal” prepared by a “qualified appraiser” as those terms are defined in the IRS regulations,

compelling and timely baseline documentation,

the land trust’s contemporaneous written acknowledgment of the gift, and

3

if applicable, a release or subordination of any mortgage on the land.

7.

Some recurring drafting issues:

Drafting and securing a tax deduction for a conservation easement require careful attention to picky details of how the transaction complies with the public purpose requirements of Section 170(h) and how the restrictions will be worded and enforced. Considerable legal sophistication is required, so it is good for the land trust to be represented by its own counsel and for it to insist that the landowner retain its own counsel.

Be sure that the land trust outlines its requirements early in the negotiation, lest the landowner be surprised by the transaction’s complexity or by some requirement that he or she might not have thought about.

Because a conservation easement defines what can and can not be done on the property following the gift, the baseline documentation report is a key document from the land trust’s perspective. It also is required to be provided by the landowner in order to secure a tax deduction. While this can be produced by the landowner, the best ones are prepared by consultants who have access to GIS mapping software, soils maps, statewide land use studies and the like. It’s worth the money to prepare a comprehensive one. Ideally, the landowner will pay the cost, but costsharing may be appropriate in some circumstances.

If the baseline document report is prepared first, which is the practice we have come to prefer, it can be used when the provisions describing the property’s conservation values are being drafted and also when the transaction is being described to the land trust’s Board.

Ideally, the land trust will have developed its own conservation easement template which will be proposed by the land trust’s counsel to the landowner’s counsel 1

. The specific transaction version should be maintained by the land trust’s counsel, so that changes from the master form can be blacklined for quick review.

Be careful of restrictions – “no hunting” comes immediately to mind – that are ambiguous or difficult to enforce. Assume the worst, including a completely uncooperative landowner, and consider how the land trust would act if the provision were violated.

Be wary of provisions that might impair the “perpetual” nature of the easement, such as landowner rights to substitute property or build

1 CLCC is working on a Connecticut template, which many land trusts may adopt as their preferred form.

4

structures on the land. Be sure that provisions of this sort are reviewed by experienced counsel.

Provide that, if the landowner (which always includes the current owner’s successors) violates the easement, the landowner will pay the land trust’s costs, including its attorneys’ fees, in enforcing the easement. This facilitates negotiations, since the landowner knows that, if it violates the easement and is taken to court, it will have to pay both its own legal costs, as well as those incurred by the land trust.

Be sure to advise the landowner that the easement can not be subject to a mortgage. This would violate the “perpetuity” requirement of Section

170(h). There is no exception to the rule. If there is a preexisting mortgage on the property, it must be subordinated to the easement. Very few institutional lenders are willing to do this, however, so give careful consideration to the impact the easement may have on whether or not future owners can mortgage the affected property.

It is in everyone’s best interest to assure that the claimed tax deduction is proper and that the IRS has no reason to audit the taxpayer’s income tax return. While it is always difficult to assign specific reasons to why the

IRS may scrutinize a particular return, it is best, we believe, if the conservation easement and the supplemental statement attached to Form

8283 tell a compelling story of how the requirements of Section 170(h) are met. Remember that the agent who will review the taxpayer’s return will know nothing about the property until he or she reads what the taxpayer has submitted. The taxpayer’s goal should be to answer every question that agent might have. Spend the time, and money, to do the job right, because in almost every case the deduction will result in substantial tax savings.

If your land trust is going to solicit or accept conservation easements, be sure that at least one member of the Board develops a specialized knowledge of them. Resources are available

2

; seek them out and spend the necessary time with them. Don’t assume that every lawyer has sufficient knowledge. Even a skillful lawyer, well versed in other areas of the law, will need to learn the necessary details. Too many times, we have received document comments from attorneys who don’t fully understand the potential adverse tax consequences of their suggestions.

2 Ideally, the land trust will join the Land Trust Alliance and participate in the activities of the Connecticut

Land Conservation Council. The LTA has published Jane Ellen Hamilton’s useful treatise entitled

Conservation Easement Drafting and Documentation . Especially helpful is Professor Nancy A.

McLaughlin’s memorandum,

Trying Times: Important Lessons to be Learned from Recent Tax Cases , which was distributed to attendees of the 2013 LTA Rally in New Orleans. It can be downloaded at this site: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2331485. The LTA Learning Center, although sometimes confusing to navigate, has a lot of very useful information. Check out www.LTA.org

.

5

While drafting conservation easements and preparing the necessary ancillary documents can be onerous chores, leave the complexities to the experts to the extent possible. Dealings with landowners should be kept as simple as possible, which is a goal that can’t always be achieved.

8.

Some thoughts about appraisals:

In various settings, representatives of the IRS have said that, once they understand the claimed public purpose benefits of the gift, they focus intently on the appraisal. Proper valuation is of paramount importance, but the calculation of that number can be exceedingly complex.

Accordingly, “qualified appraisals” of conservation easements often are very expensive. And, too, they require considerable expertise. Hire one who has the necessary credentials and, ideally, has taken the necessary continuing education courses. The IRS may disqualify certain appraisers who have written improper appraisals, but it does not maintain a list of those who are “qualified.” Ask each potential appraiser to describe his or her experience and credentials.

In broad outline, the appraiser’s calculation is a simple one. First, he or she values the land at its highest and best use as if it were free of any encumbrance. Then, the appraiser values the land subject to the proposed conservation easement and subtracts that value from the first one to determine the amount of the tax deduction. This is known as the “before and after approach.” If the land is developable, say into multiple house lots, but the conservation easement removes the development potential, the difference – and therefore the tax deduction – can be substantial. If, however, the land is an undevelopable swamp, then the conservation easement may not reduce the value of the property at all, and so in that case the taxpayer would not be entitled to any tax deduction.

Establishing the value of the tax deduction is seldom that simple, because in many cases the taxpayer owns adjacent or nearby land that might be benefitted by the donor’s gift. “

Yes, I decreased the value of the property

I subjected to the conservation easement

,” such an owner might say, “ but my other land is worth more, so my tax deduction must take into consideration both my loss and my benefit

.” This is accomplished in different ways, depending on whether the donor’s other land is contiguous or not.

If the donor owns nearby, but not contiguous, property, then the appraiser must determine whether the conservation easement enhances the value of the donor’s other property. If so, then the donor’s tax deduction must be reduced by the amount of that enhancement.

6

If the donor’s other property is contiguous to the parcel subject to the conservation easement, then the loss and benefit calculation is made in a different way. In that case, both parcels are appraised before and after the grant of the conservation easement and the tax deduction is calculated to be the net difference.

The exceedingly complex requirements of Treasury Regulation §1.170A-

14(h)(3)(i), which describes the “contiguous parcel” and “enhancement” rules, are discussed in Memorandum 201334039 issued by the IRS Office of Chief Counsel on August 23, 2013

3 . The landowner’s appraiser should know about those requirements if they are applicable.

9.

Protecting the land trust’s tax-exempt status:

As a tax-exempt entity, the land trust is required to act in accordance with the legal strictures imposed on it. While (to our knowledge), the IRS has not yet withdrawn any land trust’s tax exemption for acting improperly, it has threatened to do so if a land trust, or any other charity, abuses its privileges. We don’t know just what that means, but we never want to argue the case, either.

It’s good for a land trust to be able to say that it can’t do something -- sign a donor’s Form 8283, for instance, when it has substantial doubts about the claimed tax deduction – because to do so might risk its tax exemption.

10.

“Bargain Sales” and stewardship costs:

Ideally, the landowner will (i) pay its own surveying, legal and appraising expenses, (ii) incur the expense of preparing both a sophisticated baseline data report and the supplemental statement required to be attached to Form

8283 and (iii) contribute a stewardship fund that will pay the land trust’s anticipated long-term costs of monitoring activities on the property. If the landowner’s tax deduction is anticipated to be substantial enough, the economic benefits of entering into the transaction are still compelling, especially for one primarily interested in protecting the environmental integrity of the property.

In some cases, however, the landowner refuses to contribute a stewardship fund and insists that the land trust pay or reimburse him or her for some or all of his or her up-front costs. This can lead to a difficult negotiation and, eventually, to a characterization of the transaction as a “bargain sale.”

There is no IRS requirement that the landowner contribute a stewardship fund, although this is a very common requirement and one strongly

3 The Chief Counsel’s memorandum can be found at http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-wd/1334039.pdf

.

7

recommended by the LTA. The landowner should pay his or her own legal and appraisal costs, because those services should be rendered by truly independent advisors. While there is no IRS guidance on this, we believe (but are not certain) that the land trust can pay surveying costs and the costs of preparing the baseline data report, because it needs to have those things done in order to enforce the conservation easement.

When the land trust reimburses the landowner for legal and appraisal costs, we believe that it is proper to treat the transaction as a “bargain sale.” The reimbursed costs would be treated as the purchase price and would be listed as such on the taxpayer’s Form 8283.

11.

Two Final Suggestions: (1) Formalize the Land Trust’s Acquisition

Policies and (2) Prepare Baseline Reports Early in the Negotiation Process :

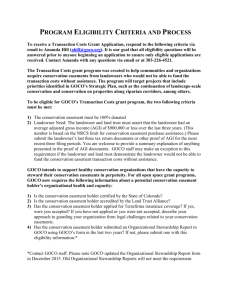

Every land trust should consider and write down its acquisition policies .

The Land Trust Alliance requires this of accredited land trusts. Especially in the case of conservation easements, the issues can be complex and it is too easy to forget important details. When are titles to be searched? Who should prepare the baseline report and when is that to be done? When are stewardship endowments required? How does the land trust communicate its requirements to landowners and what should be said about tax deductions? Many more questions such as these need to be considered and answered. The Granby Land Trust’s Land Acquisition Policy will be available on the CLCC Conference web site. It reflects what works for that organization, but it might not be appropriate for others.

Start working on the baseline report right away . This will enable the parties to fully understand what they are trying to accomplish and will facilitate the drafting of the all-important conservation purposes clauses of the easement.

12.

The advantages of conservation easements:

Landowners are often more willing to convey conservation easements than they would be to transfer full fee ownership;

They feel justifiably proud of their gifts and are thankful for the land trust’s ongoing stewardship;

Properties remain the private preserves of their owners;

Properties remain on the municipal tax rolls; and

Properly drafted documents can permanently protect the important conservation values of the affected properties.

8

13.

The disadvantages of conservation easements:

Documenting a conservation easement transaction can be complex and therefore expensive, both for the landowner and the land trust.

It is too easy draft documents that don’t meet IRS requirements, frustrating landowner expectations and, in egregious situations, threatening the land trust’s tax-exempt status;

Landowners can be frustrated with the many complications;

Negotiations can be lengthy and, sometimes, contentious; and

Ongoing stewardship can be difficult in some cases, because it can be difficult to enforce restrictions on private property, especially ambiguous or unenforceable ones.

14.

Should land trusts solicit and accept conservation easements?

Yes, certainly. Sometimes.

15.

Questions and Comments

Author’s Disclaimer

: This outline was prepared in connection with the author’s presentation at an educational session at the 2014 Conference of the Connecticut Land

Conservation Council and represents his own thinking as of the date of that Conference,

March 15, 2014. It is intended to convey general information and personal opinions, not legal advice. Every party to a conservation easement should consult his or her own legal advisors and other experts, because the issues can be complex and each situation is unique.

9