Written submission by Miranda Steward

advertisement

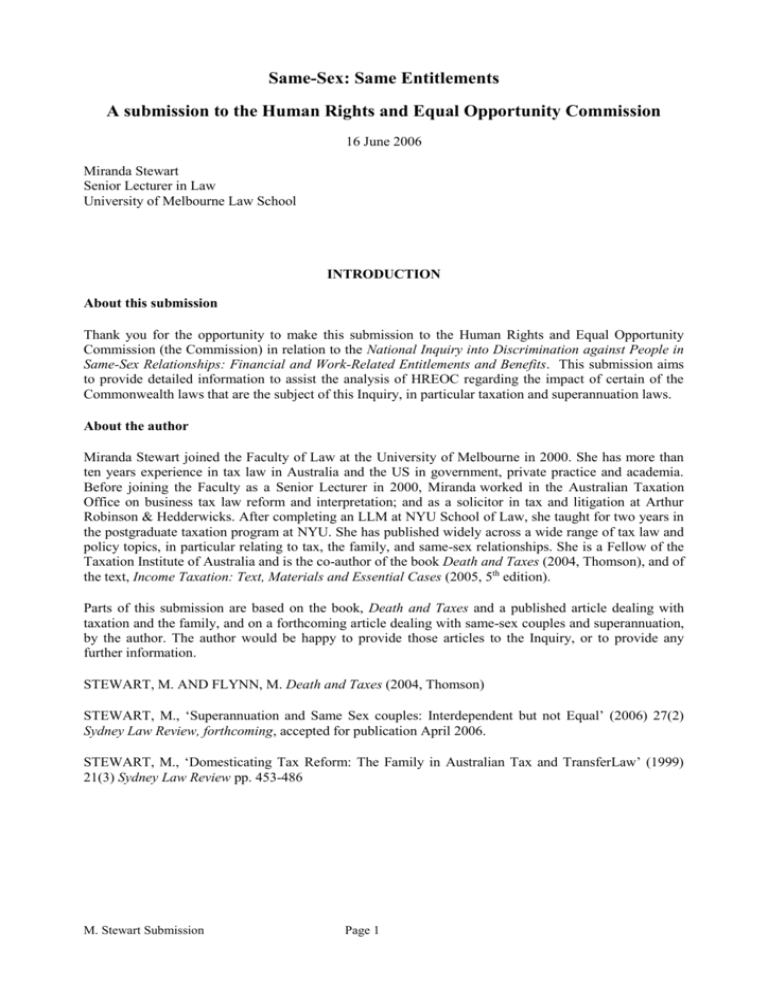

Same-Sex: Same Entitlements A submission to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission 16 June 2006 Miranda Stewart Senior Lecturer in Law University of Melbourne Law School INTRODUCTION About this submission Thank you for the opportunity to make this submission to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (the Commission) in relation to the National Inquiry into Discrimination against People in Same-Sex Relationships: Financial and Work-Related Entitlements and Benefits. This submission aims to provide detailed information to assist the analysis of HREOC regarding the impact of certain of the Commonwealth laws that are the subject of this Inquiry, in particular taxation and superannuation laws. About the author Miranda Stewart joined the Faculty of Law at the University of Melbourne in 2000. She has more than ten years experience in tax law in Australia and the US in government, private practice and academia. Before joining the Faculty as a Senior Lecturer in 2000, Miranda worked in the Australian Taxation Office on business tax law reform and interpretation; and as a solicitor in tax and litigation at Arthur Robinson & Hedderwicks. After completing an LLM at NYU School of Law, she taught for two years in the postgraduate taxation program at NYU. She has published widely across a wide range of tax law and policy topics, in particular relating to tax, the family, and same-sex relationships. She is a Fellow of the Taxation Institute of Australia and is the co-author of the book Death and Taxes (2004, Thomson), and of the text, Income Taxation: Text, Materials and Essential Cases (2005, 5th edition). Parts of this submission are based on the book, Death and Taxes and a published article dealing with taxation and the family, and on a forthcoming article dealing with same-sex couples and superannuation, by the author. The author would be happy to provide those articles to the Inquiry, or to provide any further information. STEWART, M. AND FLYNN, M. Death and Taxes (2004, Thomson) STEWART, M., ‘Superannuation and Same Sex couples: Interdependent but not Equal’ (2006) 27(2) Sydney Law Review, forthcoming, accepted for publication April 2006. STEWART, M., ‘Domesticating Tax Reform: The Family in Australian Tax and TransferLaw’ (1999) 21(3) Sydney Law Review pp. 453-486 M. Stewart Submission Page 1 SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS The income tax and superannuation laws discriminate in a range of ways against members of same-sex couples, as compared to married or de facto opposite-sex couples. The primary cause of this discrimination is the failure to include same-sex couples as ‘spouses’ in income tax and superannuation laws. In addition, income tax laws and superannuation laws discriminate against children born and raised in same-sex families. This arises both because of the failure to recognise same-sex couples as spouses and because of the failure to acknowledge in law the parenthood of a non-biological parent of a child in a same-sex relationship. RECOMMENDATION ONE It is recommended that the definition of ‘spouse’ be expanded to legally recognise same-sex couples. It is recommended HREOC review the state and territory laws concerning recommendation of same-sex domestic partners and consider the most appropriate means to extend that definition. The most straightforward way to remedy discrimination against same-sex couples in federal tax and superannuation laws is to amend the definition of ‘spouse’ to include de facto same-sex couples, so as to bring treatment into line with opposite-sex de facto couples. This has been done in many of the states and territories. For example, section 4(1) of the Property (Relationships) Act 1984 (NSW) defines a ‘de facto relationship’, in terms that apply to both same-sex and opposite-sex couples, as: “a relationship between two adult persons: (a) who live together as a couple, and (b) who are not married to one another or related by family” This would be an effective way to extend the definition of ‘spouse’ to encompass same-sex couples. However, as there is a range of ways in which this could be done, it is recommended that HREOC review the state and territory laws and determine the most appropriate formulation. RECOMMENDATION TWO It is recommended that the definition of ‘interdependency relationship’ be restricted to non-couple relationships that are interdependent, or to couple relationships that fail to meet the ‘spouse’ threshold. While the notion of ‘interdependency relationship’ in the superannuation law may have a place with respect to non-couple interdependent relationships, it is not an adequate mechanism for recognition of same-sex couples. It should be restricted to non-couple relationships or couple relationships that do not meet the full threshold for ‘spouse’ treatment. RECOMMENDATION THREE It is recommended that the children of same-sex couples be accorded full legal recognition for all federal tax and superannuation purposes. It is recommended that HREOC review in detail the treatment of children of same-sex couples, and in particular the consequences of failure to recognise the relationship between the child and his or her non-biological parent, in order to ascertain the best approach for such full recognition. This Submission discusses discrimination with respect to children of same-sex couples. This issue is complex. Mere recognition of same-sex couples, without full legal recognition of the child-parent relationship, or amendment of status of children legislation, will not remedy this discrimination. Consequently, this Submission recommends a full review of the lack of recognition and detailed consideration of the best way to ensure elimination of discrimination with respect to all children. M. Stewart Submission Page 2 DETAILED SUBMISSION INCOME TAXATION The federal government has legislated for income taxation, primarily in the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (ITAA 1936) and Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) and related legislation. The income tax law is administered by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO). There are a range of benefits in the income tax law that are not available for members of same-sex couples because of the failure to recognise same-sex couples as spouses in the income tax law, and the failure of the income tax law to fully recognise the children of same-sex couples. The definition of spouse The term ‘spouse’ is defined for income tax purposes in section 995-1 of the ITAA 1997 to be: ‘spouse’ in relation to a person, includes another person who, although not legally married to the person, lives with the person on a genuine domestic basis as the husband or wife of the person. The same definition applies for Fringe Benefits Tax purposes in section 136(1) of the Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986. There is no judicial authority that the extended meaning of ‘spouse’ or indeed, marriage itself, is confined to opposite-sex couples in Australia, although dicta in Australian and English court decisions suggests that the definition of ‘spouse’ in context of marriage cannot include same-sex relationships.1 The federal government has now legislated to limit the definition of ‘marriage’ to a man and a woman, so as to prevent the recognition by our courts of same-sex marriages formalised in other countries: Marriage Amendment Act 2004 (Cth). However, that legislation does not affect the extended definition encompassing de facto spouses in the tax law and other federal laws. There has also been no binding ruling issued from the ATO interpreting this definition expressly to exclude same-sex couples. However, the Commissioner of Taxation takes the position in a number of Interpretive Decisions2 that ‘spouse’ does not include a member of a same-sex couple. The ATO relies on a decision of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal concerning superannuation legislation, Gregory Brown v. Commissioner for Superannuation ( 1995) 38 ALD 344 at page 349; (1995) 21 AAR 378 at page 383 (discussed further below). The ATO Interpretive Decisions include: Same-sex partner is not a spouse for superannuation death benefit purposes: ATO ID 2002/731; Same-sex partner is not a spouse for superannuation contribution purposes: ATO ID 2002/649; Same-sex partner does not generate entitlement to a dependant spouse rebate: ATO ID 2002/211; No transfer of baby bonus to same-sex partner: ATO ID 2002/826; Same-sex partner is not an ‘associate’ for purposes of Fringe Benefits Tax: ATO ID 2003/7. Dependent spouse tax offset 1 Hyde v. Hyde and Woodman (1866) LR 1 P&D 130; R v L (1991) 174 CLR 379; Cth v HREOC & Anor [1998] 138 FCA; Garcia v National Australia Bank Ltd [1998] HCA 48. These decisions have not interpreted the meaning of ‘marriage’ in the Australian Constitution. 2 ATO Interpretive Decisions are anonymised published forms of decisions of the ATO concerning particular taxpayers. They are not law, nor are they binding on the Commissioner, but they provide guidance as to the ATO view on a particular matter. M. Stewart Submission Page 3 An individual taxpayer is entitled to claim a tax offset (also known as a rebate or a credit) against his or her income tax, in respect of a dependent same opposite-sex married or de facto spouse: section 159J ITAA 1936 (ATO Interpretive Decision ATO ID 2002/211). This reduces the tax owed by the individual. A dependant spouse tax offset may be claimed by a taxpayer even where they live separately and apart from their opposite-sex spouse (though not if they are divorced). This subsidy does not apply to a taxpayer with a same-sex partner. The dependant spouse tax offset has declined in significance as it has been largely replaced by the welfare payments Family Tax Benefit A and B for families with children. Nonetheless, it is still paid to a large number of taxpayers in respect of their opposite-sex spouses and remains a significant social tax expenditure, or subsidy, of the government. Together with the housekeeper and child-housekeeper rebates (mentioned below), it is estimated to cost $390 million revenue foregone in 2006-07.3 Spousal maintenance payments Maintenance payments to a spouse are not tax-deductible for an individual taxpayer as they are private expenses (section 8-1(2) ITAA 1997). However, an individual who receives maintenance payments from an opposite-sex spouse is entitled to an exemption from tax for those payments: section 51-50 ITAA 1997. This exemption would not apply for same-sex partners in recept of periodical maintenance payments. Impact of ‘spouse’ definition on other income tax offsets A range of other income tax offsets may apply in respect of the opposite-sex spouse of a taxpayer, or the spouse’s family. These would not apply in respect of the same-sex partner of a taxpayer. A housekeeper rebate may apply for a housekeeper employed full-time to care for a spouse on a disability support pension: section 159L ITAA 1936. A parent rebate may apply where a taxpayer financially supports a spouse’s parents: section 159J ITAA 1936. A medical expenses rebate may apply for a taxpayer in respect of medical expenses paid by or on behalf of a spouse: section 159P ITAA 1936. In addition, a number of income tax offsets are calculated at more generous rates or using a concessional income test, where the taxpayer has a spouse; a taxpayer with a same-sex partner would not be eligible for these concessional rules. 3 The pensioner tax rebate for a taxpayer who receives a pension from the government at a partnered rate, entitles the taxpayer to earn more income in addition to the pension before becoming liable to pay income tax. The rebate is also paid at a higher partnered rate if the taxpayer has a spouse and may be transferred to the spouse in some cases: section 160AAA ITAA 1936. The senior Australians tax offset (or low income aged persons rebate) for a taxpayer with a spouse is calculated on a higher effective combined income of the couple and may be transferred to the spouse in some cases: section 160AAAA ITAA 1936. The private health insurance tax offset is calculated for couples and families on the basis of a higher combined taxable income ceiling than for individuals: section 61-305 Income Tax Assessment Act 1997. Treasury, Tax Expenditure Statements 2005, Item A30, www.treasury.gov.au ; for a useful discussion of tax expenditures, see Julie Smith, ‘Tax Expenditures: The $30 Billion Twilight Zone of Government Spending’, Parliamentary Library Research Paper No 8 2003 M. Stewart Submission Page 4 Zone rebates for people living in rural or remote areas, the overseas defence force rebate and the civilian UN force rebate are all determined at a higher rate where the taxpayer has a dependant spouse: sections 79A, 79B, 23AB(7) Income Tax Assessment Act 1936. Capital gains tax A transfer of assets to an opposite-sex spouse or former spouse following a court order or maintenance agreement will attract capital gains tax concessions: section 126-5 ITAA 1997. Effectively, the tax on any capital gain in the assets transferred to the spouse is deferred and the gain is taxable only on the subsequent disposal of those assets by the spouse. This concession is not applicable to the transfer of an asset to a same-sex partner. CHILDREN There are a range of income tax provisions that provide concessions or offsets in respect of the ‘child’ of a taxpayer or his or her spouse. For income tax purposes, ‘child’ is defined to be the biological, adoptive or step-child of a taxpayer. As a result, tax concessions will generally be available for the biological parent of a child. However, in many same-sex families, one member of the couple is the biological parent of a child of the relationship. In this situation, the non-biological parent of the child will not generally be eligible to claim these tax concessions. Nor will the biological parent of the child be able to transfer the tax concession to the non-biological parent in the same-sex couple, as the latter is not recognised as the spouse of the biological parent. This is discussed in more detail below. The definition of ‘child’ The statutory definition of ‘child’ in section 995-1 ITAA 1997 is: ‘child includes an adopted child, step-child or ex-nuptial child’. The question of when an individual is recognised as ‘child’ of another person for federal income tax purposes is complex and is affected by state and federal legislation as well as common law definitions and presumptions.4 The statutory definition is inclusive and so it encompasses the ordinary or common law meaning of ‘child’, being the biological or ‘natural’ child of a person.5 The ordinary meaning of the term ‘child’ also includes individuals recognised under various presumptions as to parentage under the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) or under state or territory legislation concerning the status of children.6. The term ‘adopted child’ is defined in section 995-1 ITAA 1997 as a child adopted under the law of any state or territory, or another country where the adoption would be recognised as valid by a state or territory. A ‘step-child’ is not defined; however, it is generally considered that marriage is a necessary pre-requisite for existence of a step-child and a step-child is the non-biological child of the married spouse of the child’s biological mother or father. Apart from the situation of adoption, the complexities associated with determining whether an individual qualifies as a ‘child’ for tax purposes, or as a ‘child’ of a member of a superannuation fund are most apparent where the individual is not the biological child of the member of the fund. For a child of a 4 For an overview, see The Laws of Australia Vol 17 Family Law, 17.6 Status of Children and Parental Rights and Responsibilities, Parts A – C. A useful discussion is in Victorian Law Reform Commission (VLRC), Inquiry into Assisted Reproductive Technology and Adoption, Position Paper 2 – Parentage (July 2005). 5 Finlay H, R Bailey-Harris and M Otlowski, Family Law in Australia (5th ed., 1997), Para [7.7]; B v J (1996) 21 Fam LR 186; Tobin v Tobin (1999) FLC 92–848; ND v BM (Unrep., Family Court of Australia, Kay J, 23 May 2003); Re Mark (2003) 179 FLR 248. 6 The Laws of Australia, above n 4, 17.6 Part C para [12] (2). Status of children legislation includes the Birth (Equality of Status) Act 1988 (ACT) and Family Provision Act 1969 (ACT); Status of Children Act 1978 (NT); Status of Children Act 1996 (NSW); Status of Children Act 1978 (Qld); Family Relationships Act 1975 (SA); Status of Children Act 1974 (Tas.); Status of Children Act 1974 (Vic.); and, Inheritance (Family and Dependants Provision) Act 1972 (WA). M. Stewart Submission Page 5 heterosexual relationship, this situation is likely to be resolved as a result of common law and statutory presumptions as to parenting. So, the de jure or de facto spouse of the biological mother or father of an individual is likely to be presumed to be the parent of that child even though there is no biological connection. Where a child is conceived with donor sperm and born to a woman and a man in a de jure or de facto spouse relationship, she or he is likely to be recognised as the legal child of both of the spouses as a result of state and federal laws governing donor insemination.7 The problem of establishing the relationship between an individual and a non-biological parent is most acute for a child of a same-sex relationship. As a result of the lack of recognition of the relationship itself, and the failure to accord legal status to the non-biological parent, an individual will not be recognised as the ‘child’ of the non-biological parent in a same-sex relationship.8 The Family Court is empowered, and does exercise its power, to issue parenting orders in respect of non-biological parents of children in same-sex relationships, but these orders do not affect the status of the children for other purposes and in any event, such orders expire when the child reaches 18 years of age.9 First child tax offset (baby bonus) The baby bonus was a tax offset applicable for a taxpayer who became legally responsible for a child (by giving birth, adopting or in some other circumstances) between 1 July 2001 and 1 July 2004: Subdivision 61-I ITAA 1997. The bonus was applicable only where a taxpayer was the biological, adoptive or stepparent of a child; it could be transferred between the taxpayer and a spouse; this was not possible for same-sex couples. Child care tax offset As of 1 July 2005, a new childcare tax offset applies in respect of certain approved childcare costs for a child of a taxpayer: Subdivision 61-IA ITAA 1997. Eligibility for the tax offset generally speaking depends on eligibility for Childcare Benefit. It will apply based on childcare fees incurred by an individual or his or her partner; however, this will not apply for same-sex partners: section 61-490 ITAA 1997. Where a taxpayer entitled to the childcare tax offset cannot use it up in a tax year, the taxpayer is entitled to transfer it to a spouse: section 61-496 ITAA 1997. Same-sex couples are not eligible for this benefit. Child maintenance trusts On breakdown of an opposite-sex marriage or de facto couple relationship, a taxpayer may establish a child maintenance trust for the financial support of children of the relationship. The income of such a trust are exempted from the penal “children’s tax” rules that usually apply tax at (approximately) the top individual marginal rate in respect of income of minor children: Division 6AA ITAA 1936; Taxation Ruling TR 98/4. The income from such trusts is taxable at normal marginal tax rates to the trustee; where the child has no or little other income, this means that a low rate of tax will frequently apply. This is thus a concessional way in which a taxpayer can provide financially for a child on family breakdown. For a child maintenance trust to be eligible for this tax concession, the contributing parent must have maintenance obligations in respect of the child and the contributions must be made because of a family breakdown (there are also a range of other conditions). A family breakdown is defined in section 102AGA ITAA 1936 to encompass the separation or divorce of married or de facto spouses. It also applies to children of 'other relationships', where a child is born to parents who are not living together as 7 See ss.5 & 6 Artificial Conception Act 1985 (ACT); Part IIA Status of Children Act 1978 (NT); s.14 Status of Children Act (1996) (NSW); Part III Status of Children Act 1978 (Qld.); Part IIA Family Relationships Act 1975 (SA); Part III Status of Children Act 1974 (Tas.); Part 2 Status of Children Act 1974 (Vic.); ss.5,6 & 7 Artificial Conception Act 1985 (WA); and Family Law Act 1975 (Cth) s 60H(1); Re Patrick (2002) 28 Fam LR 579. 8 VLRC, Position Paper 2, above n 4, paras [3.4]-[3.5]. 9 Sec 61D Family Law Act 1975 (Cth). M. Stewart Submission Page 6 spouses at the time. However, in this case, the ATO makes clear that the child to whom property is to pass beneficially must be the ‘child’ of both parents: Taxation Ruling TR 98/4 [67]. As a result, samesex couples where one member of the couple is a non-biological parent would not be eligible to qualify to contribute to a child maintenance trust on breakdown of the relationship. Child-housekeeper rebate Where a child of a taxpayer is wholly engaged in keeping house for the taxpayer, the taxpayer is entitled to a tax rebate: section 159J ITAA 1936. This requires that the housekeeper be the biological, adoptive or step-child of a taxpayer; a non-biological child of a parent in a same-sex couple would not qualify. Other provisions A range of other provisions in the income tax law refer to the spouse or family of a taxpayer. Many of these provisions are integrity or anti-avoidance provisions. For example, a taxpayer is not entitled to deduct a payment to a “relative” that exceeds a reasonable amount: section 26-35 ITAA 1997. A “relative” includes a taxpayer’s spouse; a parent, grandparent, brother, sister, uncle, aunt, nephew, niece, lineal descendent or adopted child of the person; or such a relative of the taxpayer’s spouse; or the spouse of one of such specified relatives: section 995-1 ITAA 1997. For completeness, it must be noted that a same-sex partner, or relatives of that same-sex partner, would not be included in this list of relatives. It is most important to note, however, that until equal treatment under the law is extended to same-sex couples it would be unfair and doubly discriminatory for the notion of spouse or family to be extended include a member of a same-sex couple for purpose of integrity provisions such as that described above. SUPERANNUATION Superannuation is the major way in which Australians save for retirement and superannuation savings now total more than $741 billion.10 Superannuation funds are governed primarily by the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (the SIS Act) and corresponding Regulations, and are primarily regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA). The superannuation regime combines compulsory contributions by Australian workers and employers under the Superannuation Guarantee Scheme,11 with tax concessions in respect of contributions, earnings in the superannuation fund and benefit payments, in the ITAA36 and ITAA97. The tax concessions for superannuation are Australia’s largest tax expenditure, estimated at $16.235 billion in revenue foregone in 2006-07.12 In the 2006-07 Budget, the Commonwealth Government proposed significant reforms to the superannuation regime which would further increase the value of these concessions by completely exempting most superannuation benefit payments on retirement or at death.13 These changes will have an impact on the superannuation consequences for same-sex couples, but until legislation is introduced it is difficult to state exactly what that impact will be. However, the fundamental discrimination in the superannuation law, arising from a failure to recognise same-sex couples in almost all circumstances, seems likely to remain after those changes are implemented. 10 Minister for Revenue the Hon Mal Brough MP, Super Savings Continue Strong Growth: Press Release No. 089 (13 October 2005). 11 12 13 Superannuation Guarantee Charge Act 1992 (Cth) and associated legislation. Treasury, Tax Expenditures Statement 2005, Item C1, above n 3. Australian Government, A plan to simplify and streamline superannuation (9 May 2006). The proposals are currently undergoing public consultation and may be subject to alteration; no legislation has been introduced as yet. See further http://simplersuper.treasury.gov.au . M. Stewart Submission Page 7 There are a range of discriminatory outcomes caused by the failure to recognise same-sex couples in superannuation legislation. In addition, there are a range of income tax concessions for superannuation that will not apply to same-sex couples or their children because of this discriminatory lack of recognition. These issues are discussed below. The definition of spouse The term ‘spouse’ takes its general law meaning as including legally married spouses and is extended in the SIS Act in identical terms to the income tax law, to include de facto opposite-sex spouses under section 10(1) SIS Act: ‘spouse’ in relation to a person, includes another person who, although not legally married to the person, lives with the person on a genuine domestic basis as the husband or wife of the person. This definition is interpreted by APRA, not to include same-sex relationships.14 The basis for that interpretation is the Administrative Appeals Tribunal decision on a similar, but not identical, provision in the Superannuation Act 1976 (Cth) (Re Brown and Commissioner for Superannuation (1995) 21 AAR 378 Para [57]). Superannuation spouse tax offset Where a member of a superannuation fund makes contributions to the fund in favour of his or her de jure or de facto opposite-sex spouse,15 and the spouse’s assessable income and reportable fringe benefits for the fiscal year are less than $13,800, the contributor is entitled to a tax offset, or rebate, in respect of maximum ‘eligible spouse contributions’ of $3,000 in a year (sections 159T and 159TC ITAA 1936). As mentioned above, this does not apply for same-sex partners. The spouse tax offset can reduce the income tax payable by the contributing spouse by up to $540 each year (section 159TA ITAA 1936). These contributions enable a ‘spouse’ who is not earning salary or wages, or who is earning only limited salary income, to accumulate savings in this tax-favoured vehicle, subsidised by his or her spouse. They may be made in addition to any contributions made by the spouse him- or herself in each year. This tax expenditure is estimated to cost $13 million in revenue forgone in 2006-07.16 Spouse contribution splitting On 1 January 2006, amendments were introduced to the SIS Act to permit a member to split his or her employer contributions or personal contributions with their spouse.17 With respect to personal contributions, up to 85% of a member’s deductible contributions and 100% of his/her non-deductible contributions can be split to the spouse.18 Under the current superannuation regime, concessional tax of 15% applies up to an amount called the Reasonable Benefit Limit (RBL) threshold. The key benefits from contribution splitting are that the couple (comprising the member spouse and the receiving spouse) will each have access to their individual Eligible Termination Payment (ETP) low-rate threshold and a Reasonable Benefit Limit (RBL) threshold. In other words, spouses who split their superannuation contributions receive beneficial 14 15 16 17 Superannuation Circular No. I.C.2 (March 1999) ATO Interpretive Decision ID 2002/649. Tax Expenditures Statement 2005, Appendix B, Table B1. Tax Laws Amendment (Superannuation Contributions Splitting) Act 2005 (Cth). New sec. 27A(1) “contributions-splitting ETP” and new s 27D(4) ITAA 1936; see also Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Amendments Regulations 2006 No. 8, registered 15 December 2005, inserting new Division 6.7 on spouse contributions splitting amounts. 18 M. Stewart Submission Page 8 tax treatment. This is not available to same-sex couples, as they do not fall within the definition of spouse, notwithstanding that same-sex couples, particularly those who are in committed long term relationships, are emotionally and financially interdependent on each other and arrange their financial affairs in very much the same way as married or de-facto opposite-sex couples. On introduction of spouse contribution splitting, one commentator noted, ‘super contributions splitting will provide a splendid opportunity for couples to reconsider their retirement strategies’.19 The 2006 budget announcement by Mr Costello proposes to abolish all tax payable on superannuation benefits if cashed after age 60, including the abolition of the Reasonable Benefit Limit for all individuals. Assuming that this proposal is passed, the tax benefits obtained from spousal contribution splitting may become less valuable. Nonetheless, they remain in the SIS Act and income tax law and provide a means for an individual to provide a superannuation balance for his or her low-income spouse, a concession which will not apply for same-sex couples. Spousal contribution splitting thus permits a heterosexual couple to have the benefit two RBL thresholds instead of one, thereby providing them with a more advantageous tax position than is available for samesex couples. Superannuation death benefits paid to a ‘dependant’ A member of a superannuation fund may be entitled under the terms of the fund to a death benefit (which operates rather like a life insurance benefit). Under the SIS Act, a trustee of a superannuation fund must pay a death benefit to ‘the member’s legal personal representative, to any or all of the member’s dependants, or to both’.20 The Budget proposal to remove the RBL ceiling on death benefits paid to ‘dependants’ will make these lump sums more attractive, and so makes the associated discrimination against same-sex couples more acute. Requirement for a dependant under the SIS Act The definition of ‘dependant’ in the SIS Act establishes the class of individuals who are entitled to receive a death benefit from a fund. If more than one dependant is located, the trustee may allocate the death benefit between them in a manner that the trustee considers fair and reasonable in exercise of his or her discretion. Only if neither the legal personal representative (LPR) nor dependants can be found is the trustee empowered, but not required, subject to the trust deed, to pay out some or all of the death benefit to another person. Identifying the LPR and dependants and making distributions on death are significant issues for superannuation trustees. An indicator of the contentious nature of these distributions is that complaints about distribution of death benefits made up 28 percent of the complaints to the Superannuation Complaints Tribunal in 2004, the largest category for that year, and comprised the largest or second-largest category of complaints in previous years.21 Thus, it is important that the law as to ‘dependants’ should be as clear as possible to minimise such disputes. A member of a fund may be entitled under the terms of the trust deed to submit a binding death nomination, although in many cases members can only nominate their preferred beneficiaries. Even if the trust deed of a superannuation fund permits binding death nominations, the trust deed will at all times still be subject to the provisions of the SIS Act and Regulations. A binding death nomination will only be valid and thus binding on the trustee if the nominated beneficiary is the member’s legal personal representative or a dependant. In any event, it requires active nomination of a partner, rather than applying automatically as is the case for opposite-sex spouses, and will also only last for 3 years and so must be kept up to date. In reality, trustees often exercise their discretion in favour of a deceased’s husband or wife (whether married or de-facto) because of the status attached to such relationships (see, e.g. Superannuation 19 Daryl Dixon, ‘Splitting contributions will give couples useful options’, Sun-Herald 23 October 2005. 20 Sec. 62(1) (b) (iv) and (v) of SIS Act; Reg 6.22 of SIS Regs. 21 Superannuation Complaints Tribunal, Annual Report 2004, p31-32 (Table 2). M. Stewart Submission Page 9 Complaints Tribunal Determination No. D00-01\103). On the other hand, same-sex relationships are open to more scrutiny and a greater degree of proof is required to persuade the trustee to exercise its discretion in favour of the same-sex partner. This results in greater uncertainty and injustice for the surviving same-sex partner, especially where the deceased’s family is hostile and makes a competing claim for the death benefits (see, e.g. Superannuation Complaints Tribunal Determinations D01-02\212 (28 February 2002); D05-06\061 (30 May 2005)). Tax concessions for superannuation death benefits paid to dependants A death benefit ETP paid to a ‘dependant’ as defined in the ITAA 1936 is exempt from income tax in the hands of the dependant, up to the pension RBL of the deceased member of the fund (the pension RBL was $1,297,886 in 2005-06).22 When the tax treatment of the contributions and earnings in the superannuation fund is taken into account, this means that a superannuation death benefit paid to a dependant is taxed at an overall rate of 15 percent. In contrast, where a death benefit is not paid to a dependant as defined, the element over and above any undeducted contributions to the fund by the deceased will be taxed at a rate of 15 percent in the hands of the recipient.23 Lump sum payments from a superannuation fund directly to a dependant are the most common type of death benefit ETP.24 A payment made to the LPR of a deceased member from a superannuation fund will not qualify for tax exemption unless passed on to a dependant as defined. The income tax exemption can also apply to lump sum payments from the employer of the deceased, paid to the LPR and passed on to a dependant;25 lump sum payments from an Approved Deposit Fund;26 lump sum payments on death of the holder of certain annuities;27 and payments in respect of small superannuation accounts or superannuation guarantee shortfall payments.28 Who is a dependant? The definition of ‘dependant’ in the SIS Act and ITAA 1936 is similar but not identical. The definition of ‘dependant’ in section 27A(1) ITAA 1936 read: ‘dependant’, in relation to a person (the first person), includes: … (b) … (i) and any spouse or former spouse of the first person; (ii) any child, aged less than 18 years, of the first person; and (iii) any person with whom the first person has an interdependency relationship.’ Spouses and children Sec. 27A (1) ‘ETP’ para (ba) and Sec. 27AAA (4) of IT Act 1936. As for other ETPs, amounts in excess of the RBL are taxed at a 47% rate. 22 23 Sec. 27AA, 27AB of IT Act 1936. 24 A death benefit ETP can include the commuted value of a pension from a fund: Sec. 27AAA (2) at Item 4 and s 27AAA (7) of IT Act 1936. The commutation lump sum must be paid within the longer of 6 months of the deceased’s death or 3 months of the grant of probate or letters of administration. 25 26 27 Sec. 27A (1) ‘‘eligible termination payment’’ para (aa); s 27A (3) (b) of IT Act 1936. Sec. 27A (1) ‘eligible termination payment’ para (c), s 27A (3) (b) of IT Act 1936. Sec. 27A (1) of IT ACT 1936. This applies when the annuity was purchased after 12 January 1987. Sec. 27A (1) ‘eligible termination payment’ paras (fd), (ff); sec. 27A (3) (b) of IT Act 1936. These are payments under sec. 76(7) of Small Superannuation Accounts Act 1995 (Cth) and any ‘‘shortfall component’’ paid under sec. 67 of Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth). 28 M. Stewart Submission Page 10 As discussed above concerning income taxation, the definition of ‘spouse’ and ‘child’ in the income tax law exclude same-sex couples and the child of a non-biological parent in a same-sex relationship. It is notable that the problem of failure to recognise all child-parent relationships is not entirely remedied by the new concept of interdependency relationship, discussed below. The following example illustrates the failure to recognise the child of a same-sex couple for superannuation and tax purposes. Example. Helen and Jane are co-mothers of Anna. Anna is the biological child of Helen, conceived by anonymous donor insemination. Helen and Jane live together as a couple and both contribute to the parenting, financial support and care of Anna. To ensure recognition of Jane’s status as a responsible parent for Anna and in Anna’s best interests, they have obtained a parenting order from the Family Court in respect of Jane. Jane dies when Anna is aged 3. Anna is unlikely to qualify as a ‘child’ of Jane in spite of the parenting order (although clearly a ‘child’ of Helen, her biological mother). Consequently, Anna is not entitled to benefits from Jane’s superannuation fund on this basis. The lack of status accorded to children of same-sex relationships leads to an outcome that is clearly discriminatory and is not in the best interests of those children. Financial dependence Until 2004, a member of a same-sex couple had to rely on producing evidence of financial dependence in order to be eligible to receive a superannuation death benefit but would still not be eligible for income tax concessions as a result of the moire restrictive tax law definition. The definition of ‘dependant’ encompasses an individual who is dependent on a member of a superannuation fund in the ordinary meaning of the term, a question of fact to be determined at the time of death of the member of the fund.29 Financial dependence has been emphasised by APRA and the ATO. APRA guidelines state that ‘dependant’ in the SIS Act means ‘any person who was financially dependent on the member at the time of the member’s death’.30 APRA emphasises that ‘it is the trustee’s responsibility to decide’ whether a person was financially dependent.31 As trustees are required to exercise caution, it is necessary for an individual to produce evidence to prove financial dependence on the deceased member of the fund. The ATO may take a stricter approach than APRA, as it requires that a ‘dependant’ is one who is ‘‘actually dependent upon the deceased taxpayer for maintenance or support’’.32 Interdependency relationships Commencing 1 July 2004, the concept of ‘interdependency relationship’ was introduced into both the SIS Act and the IT Act 1936, thereby establishing a fourth means by which a person may qualify as a ‘dependant’. The new concept of ‘interdependency relationship’ has been stated by the government to cover same-sex couples.33 However, it is clear that it is not intended to, and does not, produce equality between same-sex couples and either married or de facto opposite-sex spouses. 29 Kauri Timber Co (Tas) Pty Ltd v Reeman (1973) 128 CLR 177; Aafjes v Kearney (1994) 180 CLR (Full High Court), per Barwick CJ at para [7]. 30 APRA, Superannuation Circular No. I.C.2 (March 1999), para [14] 31 APRA, Superannuation Circular No. I.C.2 (March 1999), para [14] 32 Income Tax Ruling IT 2168, para [41] (28 June 1985); ATO Interpretive Decision ID 2002/731. Minister for Revenue and Assistant Treasurer Senator Helen Coonan, Press Release C046/2004 ‘Fairer Treatment for Interdependent Relationships’, 27 May 2004. 33 M. Stewart Submission Page 11 An ‘interdependency relationship’ is defined in section 27AAB of ITAA 1936 and in section 10A SIS Act as follows: Sec 27AAB Interdependency relationship (1) Subject to subsection (3) ... 2 persons (whether or not related by family) have an interdependency relationship if: (a) they have a close personal relationship; and (b) they live together; and (c) one or each of them provides the other with financial support; and (d) one or each of them provides the other with domestic support and personal care. (2) Subject to subsection (3), … if: (a) 2 persons (whether or not related by family) satisfy the requirement of paragraph (1)(a); and (b) they do not satisfy the other requirements of an interdependency relationship under subsection (1); and (c) the reason they do not satisfy the other requirements is that either or both of them suffer from a physical, intellectual or psychiatric disability; they have an interdependency relationship. (3) The regulations may specify: (a) matters that are, or are not, to be taken into account in determining under subsection (1) or (2) whether 2 persons have an interdependency relationship; and (b) circumstances in which 2 persons have, or do not have, an interdependency relationship. This new concept has been further explained in Regulations assented to on 10 November 2005.34 The concept of ‘interdependency relationship’ draws on New South Wales state law. Section 5(1) of the Property (Relationships) Act 1984 (NSW), as amended in 1999, recognises as a ‘domestic relationship’: ‘(a) a de facto relationship, or (b) a close personal relationship (other than a marriage or de facto relationship) between two adult persons, whether or not related by family, who are living together, one or each of whom provides the other with domestic support and personal care.’ (emphasis added) Section 4(1) of the Property (Relationships) Act 1984 (NSW) defines a ‘de facto relationship’, in terms that apply to both same-sex and opposite-sex couples, as: a relationship between two adult persons: (a) who live together as a couple, and (b) who are not married to one another or related by family. 34 New Income Tax Reg 8A in Income Tax Regulations 1936; new Reg 1.04AAAA Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994. The Regulations are in identical terms. M. Stewart Submission Page 12 The Property (Relationships) Act 1984 (NSW) clearly contemplates that a same-sex couple who live together will usually qualify as a ‘de facto relationship’ and will thus fall into the first limb of the definition of ‘domestic relationship’ in section 5(1)(a) of that Act. The second limb of the definition of ‘domestic relationship’ is thus intended to cover relationships other than couple relationships where the couple is living together. That second limb incorporates some specific criteria to further delimit those non-couple relationships that will meet the threshold of a ‘domestic relationship’: specifically, the parties must live together and one or each must provide the other with domestic support and personal care. The new definition of ‘interdependency relationship’ in the SIS Act and ITAA 1936 adopts almost word for word the second limb of the definition in section 5(1)(b) of the Property (Relationships) Act 1984 (NSW), with the addition of a requirement of financial support. This is problematic, as it squeezes samesex couples into a definition which was specifically drafted to deal with non-couple relationships, and which contains a long list of criteria, all of which must be satisfied. The definition of ‘interdependency relationship’ contains four, or perhaps five, separate criteria that must be satisfied. Most importantly, the criterion requiring ‘domestic support and personal care’ is over and above the usual requirements for a de facto spouse relationship. The potentially narrow compass of the notion of ‘personal care’, particularly as it might apply to a same-sex couple, is demonstrated in two New South Wales cases concerning the application of the Property (Domestic Relationships) Act 1994 (NSW): Dridi v Fillmore35 and Devonshire v Hyde.36 The detailed interpretation of the new concept and associated Regulations is complex; see the attached article for further details. In sum, the approach significantly constricts the scope of the concept of ‘interdependency relationship’ and will lead to continued unequal treatment for same-sex couples compared to opposite-sex de facto spouses. It is an inappropriate mechanism for recognition of couple relationships. It should be restricted to non-couple interdependent relationships, or to couples that fail to meet the threshold for married or de facto spouse relationships. Public sector superannuation Australian government employees are members of either the Public Sector Superannuation Accumulation Plan (PSSap), the Public Sector Superannuation scheme (PSS) or the original Commonwealth Superannuation Scheme (CSS). These schemes are administered under trust deeds established by legislation and contain specific definitions setting out who may benefit from payouts on death of a member. In the PSSap, for employees hired on or after 1 July 2005, ‘dependant’ has the same meaning as in the SIS Act and death benefits are payable to dependants or the LPR of the deceased, similarly to other superannuation funds.37 Consequently, the new notion of ‘interdependency relationship’ applies for new members of the PSSap. Similarly, in the Accumulation Plan that operates under the PSS, that broad definition of ‘dependant’ applies.38 However, in the CSS and in the PSS defined benefit plan, death benefits are limited to opposite sex ‘spouses’ who are in a ‘marital relationship’ with the deceased member of the fund.39 A ‘marital relationship’ exists where two people have ordinarily lived together as husband and wife in a permanent and bona fide domestic relationship for a continuous period of at least three years prior to the date of death. Factors to be considered include the length of the relationship; whether the persons were legally married, financial dependence, whether there were children of the relationship, joint ownership of 35 [2001] NSWSC 319 36 [2002] NSWSC 30 37 Commonwealth Superannuation Act 2005 (Cth); Cl 1.2.1 and Cl 3.2.2 of Sch. 1 of the PSSap Trust Deed. 38 Commonwealth Superannuation Act 1990 (Cth) and Cl A.1.2 of Sch. 1 of the PSS Trust Deed. 39 For the CSS, see Commonwealth Superannuation Act 1976 (Cth) sec. 8A, 8B and Part VI; see also Death Benefits, http://www.css.gov.au/css/benefits/death_benefits.html. For the PSS, see the Trust Deed, Cl B.1.2.1, definition of ‘marital relationship’ and Part B.7 of Sch. B, and Death Benefits, www.pss.gov.au/pss/benefits/death_benefits.html. M. Stewart Submission Page 13 property and other evidence. The AAT has construed these provisions as requiring that the persons must be of the opposite sex, as inherent in the words ‘husband’ and ‘wife’.40 These provisions were not amended to incorporate the notion of ‘interdependency relationship’. A similar restriction to opposite-sex spouses in a ‘marital relationship’ applies for Defence Force personnel.41 The most recent Defence Force superannuation regime explicitly provides in relation to member contributions that ‘a person is not, for the purposes of these Rules, a spouse in relation to another person if he or she is of the same sex as that other person.’42 Ironically, the notion of an ‘interdependent relationship’ has now been adopted in the Defence context, for the purpose of recognising same-sex couples in relation to housing, education assistance, relocation and compensation.43 However, this change does not extend to the provision of veteran’s benefits or superannuation. Reversionary pensions A member of a superannuation fund may be in receipt of benefits, after retirement or disability, as a pension (or income stream) from the fund rather than as a lump sum. A superannuation pension may be ‘reversionary’ such that it will revert automatically to another nominated person on death of the pensioner. Most trust deeds only allow for reversion of a pension to a de jure or de facto spouse, which does not include a partner in a same-sex relationship; as a result, trustees have refused to pay reversionary pensions to surviving members of same-sex relationships.44 As the ‘interdependency relationship’ reform has not actually amended the meaning of ‘spouse’, an amendment of trust deeds to include a same-sex partner in this category may breach the SIS Act. Under the recent proposals to reform superannuation, reversionary pensions would be limited by statute to spouses and would therefore not be allowed for a surviving member in a same-sex couple. Family law splitting of superannuation on relationship breakdown Under the Family Law Act, superannuation lump sums or pension and annuity entitlements may now be split in accordance with an agreement or order on relationship breakdown without adverse tax or superannuation consequences. As same-sex couples are not covered by the Family Law regime, they will not be eligible for this treatment. 40 Brown v Commr for Superannuation (1995) 38 ALD 344 41 Sec. 6A and 6B of Defence Force Retirement and Death Benefits Act 1973 (Cth); and Form of Trust Deed, Sch 1Glossary, Part 5 ‘spouse’, in Sch. to Military Superannuation and Benefits Act 1991 (Cth). 42 Military Superannuation and Benefits Act 1991 (Cth), Sch., Form of Trust Deed, Part 2 Rule 7. 43 Defence Bulletin DFS /2005, effective as of 1 December 2005. 44 This was alluded to by Mr Anthony Albanese, MP in his evidence before the Senate Select Committee, Same Sex Reference, Hearings 3 March 2000, p13, above n 58. M. Stewart Submission Page 14