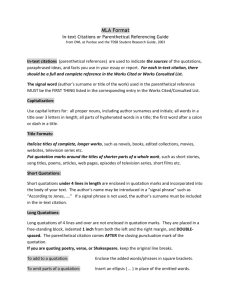

Integration of Quotations

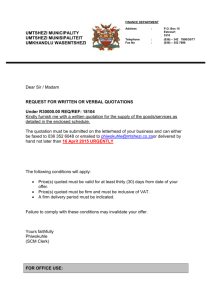

advertisement

ENGL197 G – H2 Writing in the English Discipline English 197 G | Handout #2 - Integrating Quotations Overview The citation of other texts in your own writing is an essential aspect of participation in academic discourse. Citations demonstrate scholarly rigor to your reader and provide a textual basis for your own insights. They also function to situate your writing in a conversation of texts by other scholars. Strategy: Some Common Reasons for Quoting Critical Texts 1. To Identify a Problem or Line of Inquiry – very often scholars take up or modify a line of inquiry already circulating in published texts, using a previous question to discuss a new facet of the topic, point out problematic assumptions, or build on the understanding of the inquiry so far. This strategy is very useful in introductory phases of an essay. 2. To Clarify or Establish an Idea – this is perhaps the most general and common strategy for quotation: to explain and clarify a point made in another text that connects with your topic. Quoting a text for clarification is helpful in establishing a concept, key term, or method you which to use in some way. 3. To Support or Document an Idea – sometimes you just want to demonstrate the rigor of your inquiry by showing that other scholars have thought likewise, or that a certain idea is already in the academic conversation on your topic. Also, you may need to document, very literally, that something actually appeared in a text. 4. To Make a Distinction or Comparison – many times you will read about a concept, term, or method that seems incomplete or overly simplistic. This strategy is often used to introduce a helpful distinction into the discussion, or to create a meaningful contrast by comparison that allows new insight into the topic. 5. To Analyze Rhetoric – the phrasing in texts always suggests a particular approach which entails specific assumptions and emphases. Sometimes you will want to analyze how something is being presented in a text in order to discuss problems in method, bias in approach, or, conversely, to demonstrate that the author is already aware of these issues. This is a very helpful strategy to use in critiquing claims or descriptions in other texts. Citation Type: Deciding Whether to Quote or Reference the Text Stylistically speaking, there are two types of citation: quoting and referencing. Both are forms of academic citation, and all citation styles have rules for these two types. 1. Quoting a text is when you insert actual language from another text purposefully into your own. 2. Referencing is when you simply describe or paraphrase a text in your own words and attribute the ideas to the other text in a citation. Most academic texts involve a combination of these two types, depending on the function of the citation in the writer’s argument. When deciding whether to quote or reference, ask the following: 1. 2. 3. 4. Are you going to comment on the actual language of the passage (word choice, phrasing)? Are you going to comment on the sequencing or structure of the passage? Are you making a comparison to another passage? Are you going to reference the passage frequently in what follows? If the answer is Yes to any of the above, you want to quote the passage rather than simply reference it. ENGL197 G – H2 Integration - Technical: How to Integrate Quotations into Your Prose Technically, there are 3 ways to integrate quotations into your own writing: 1. As an independent clause of your sentence: Ex. One of the general qualities Anderson attributes to pre-modern imagined communities, and especially religious community, is centrality: “All the great classical communities conceived themselves as cosmically central, …” (13). 2. As a dependent clause of your sentence: Ex. When Anderson first argues that it is the “magic of nationalism to turn chance into destiny” (12), he does not provide much detail on how this “magic” functions differently than the correspondent quality in religious community. 3. As a grammatically seamless part of a sentence: Ex. In his description of the emergence of nationalism Anderson argues that “the two relevant cultural systems are the religious community and the dynastic realm” (12). Integration - Conceptual: How to Integrate Quotations into Your Argument Conceptually speaking, the purposeful integration of quotations (as ideas) into your own argument requires that you: 1. Introduce the quotation in your prose beforehand by signaling to and preparing the reader for the inclusion of a new idea. 2. Purposefully explicate the quotation in your prose afterward by explaining exactly what the quotation means and why the quotation is significant in the context of your topic. The explication process is dependent on what you are trying to do with the quotation (see “Strategy” section above), but may often involve things like explaining the immediate context of the quotation, explaining the overall context, providing some analysis of what is said in the quotation, identifying a key term, and so on. The essential point is that you should NEVER just plop a quotation into your prose and assume that the reader understands exactly how you want them to understand it, or that it can simply stand in for your own thinking. Example of Purposeful Use of Quotations In the first letter of The Coquette, Eliza relates to her friend some final words of Mr. Haly, her recently deceased would-be husband, which indicate what Anderson might call a pre-modern community perspective: “There is . . . but one link in the chain of life, undissevered; that, my dear Eliza, is my attachment to you. But God is wise and good in all his ways; and in this, as in all other respects, I would cheerfully say, His will be done” (6). This comment demonstrates Haly’s pre-modern sensibility: he attributes the experience of life and death to a divine will, and he thinks of life as a unified and singular “chain,” suggesting that “cosmologically central” view of community that Anderson underscores (13). As a writer, Foster challenges and complicates this sensibility with qualities from what Anderson attributes to national consciousness (as a contrast to the premodern sensibility of religious community and the dynastic realm). For example, Eliza’s character demonstrates a tension between her affirmation of Haly’s pre-modern order and the “unusual” pleasure that she feels in her being severed from perceived constraints by Haly’s death. There is evidence of an awareness of pre-modern order: she is to be stewarded by a male, evinced by the transfer of guardianship from her parents to Haly; she also affirms a destiny marked by divine will, as well as the hierarchical social order in which her place as a woman is restricted. However, Eliza also desires lateral relationships – friendship – over and above the order she indirectly affirms in her mourning of Haly. That Eliza wishes “no other connection than that of friendship” is an important emphasis, since it would have been in contrast to the duties of a woman in the imaginations of Foster’s readers….