2001 Suffolk Transnational Law Review

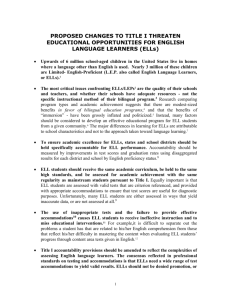

advertisement