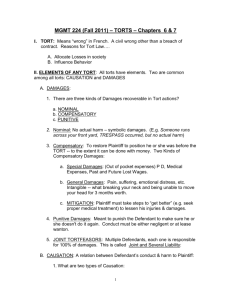

Torts - Taylor - 2008-09 (3)

advertisement