recent ramblings in astro

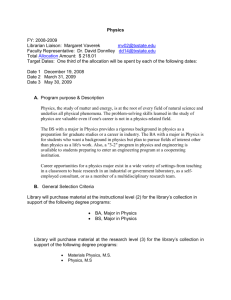

advertisement

RECENT RAMBLINGS IN ASTRO-ART RELATIONSHIPS ANDRE HECK Strasbourg Astronomical Observatory, 11 rue de l'Université’, F-67000 Strasbourg, France heck@astro.u-strasbg.fr ABSTRACT. After listing a series of findings and discoveries in terms of relationships between astronomy and art in the broad sense, we detail two specific cases: Pierre Charles Le Monnier as painted by Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié and the series of adventures of Tintin by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. A brief progress report is also offered for the field of socio-dynamics of astronomy introduced at INSAP II. 1. Introduction This contribution is the continuation of the talk given at INSAP II which detailed the case of Belgian painter Paul Delvaux (1897-1994) with his beautiful work entitled ‘Les Astronomes’ (The Astronomers, 1961) and the three earlier versions of ‘Les Phases de la Lune’ (The Phases of the Moon, 1939, 1941 & 1942). Works by Giacomo Balla (1871-1958) and Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997) were also described. As some readers know, I am publishing under a pseudonym monthly chronicles in a couple of European astronomy magazines 1.Those notes cover various topics: news, history, documentaries, reflections, original fictions, legends collected during trips around the world, and so on. In the course of those exercises, I had also the opportunity to encounter a number of ‘crossovers’ between astronomy and arts in general over the past two years: - in sculpture, Charles O. Perry with his ‘Eclipse’ (Al Nath 1999a), - in photography, Abelardo Morell and his original juxtapositions (Al Nath 1999b), - in engraving, Maurits Cornelius Escher with his unusual perspectives (Al Nath 1998), - in painting, works by Jan Vermeer with his `Astronomer' 2, Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié (see below) and Brigid Collins (Heck 2000a), - in literature, quotations by Ernest Hemingway (Al Nath 2000a) and Victor Hugo (Al Nath 2001), as well as in other disciplines such as construction (Gustave Eiffel – Al Nath 2000b) and going as far as advertising (German ads for BMW and Peugeot cars) and the classical Belgian schools of cartoon strips (see below). As shown in the bibliography, I have investigated fairly well a few cases myself. Others would deserve more research and perhaps someone will take up one of them for presentation at a future INSAP conference. The following sections will be devoted to two specific `crossovers'. 1 See for instance http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/~heck/p-potins.htm The question remains whether the person pictured is the astronomer Christiaan Huygens (whom Vermeer had befriended) or just an extra hired as a model for the main purpose of rendering the atmosphere of an astronomer's workshop. 2 2. Hanging in Portugal The museum of the Foundation Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal, displays an oil on canvas simply entitled ‘L'astronome’ (The Astronomer). Due to NicolasBernard Lépicié, that painting dates back to 1777 and represents Pierre Charles Le Monnier (1915-1799), thus at the beginning of his sixties. The painting is rather classical for the time, focussing on the central character while adding a couple of elements typical of the function: a small refractor on a table and an optical piece in the hands of the gentleman. But Le Monnier himself is a very interesting character. He was the privileged astronomer of King Louis XV of France. Professor at the Collège de France from 1746 onwards, assiduous observer, he has been the first master of Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande. Still quite young, he had the chance to be a member of the expedition led by Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis in Lapland (1736-1737) to measure an arc of meridian in parallel with another expedition in Peru (1735-1744)3 Maupertuis would leave Paris again in 1745 to reorganize the Academy of Berlin at the request of King Friedrich II of Prussia, He would get married there, but also have some trouble with Voltaire who became jealous of his friendship with the king (Voltaire had ultimately to leave Berlin). Le Monnier significantly contributed to the progress of astronomical measurements in France. As he was fluent in English, he translated and `advertized' in France the works of some of his British colleagues (Flamsteed and Newton for example). He also observed a dozen times the 5th-magnitude object that was Uranus before it be identified as a planet. And, according to what might be a legend, he wrote down his observations on the bag holding his wig powder ... 3. Belgian Delicacies There are two Belgian classical schools of cartooning (referred to as the ‘ninth art’ in the country): Brussels and Marcinelle-Charleroi. They have reached a world-wide fame. For instance, the adventures of the young reporter Tintin, by Hergé (Georges Rémi, 19071983) from the Brussels' school have been translated into about fifty languages and sold to about 200 millions copies. Presenting their astronomy-related features would be the matter for a full lecture, but the high fees requested by Hergé’s heirs might be a serious motive for not reproducing his drawings in proceedings and thus for removing any real interest to the exercise. In ‘L’Étoile mystérieuse’ (The Shooting Star, 1941-42), Hergé pictures correctly the Big Dipper (called the Great Bear in the English version) as well as a large refracting telescope on a German mount (fortunately not sticking out of the dome as seen too often in cartoons). Tintin is meeting a couple of weird astronomers, including the human calculator of the place. The spider frightening Tintin and his dog Milou (Snowy) should however not have been seen through the telescope as it was crawling on the objective lens surface, totally out of focus. In ‘Le temple du Soleil’ (Prisoners of the Sun, 1946-48), Tintin saves himself and his 3 See the book (in French) by Florence Trystam (1979) dealing with the story of the Southern expedition and that reads like a novel: a compendium of dirty tricks scientists can play to each other ... companions from burning at the stake by seemingly talking to the Sun and provoking a total solar eclipse - something reminiscent of what Cristóbal Colón is said having done in order to impress Indians when he discovered the New World. Fig. 1. Pierre Charles Le Monnier by Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié (oil on canvas, 0.91 x 0.72 cm2 , Courtesy Museum Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon) But the most interesting Tintin stories for our purpose - those that have certainly inspired more than one astronomy- or space-related vocations - are definitely ‘Objectif Lune’ and the continuation ‘On a marché sur la Lune’ (Destination Moon and Explorers of the Moon, 1950-53), produced well before the beginning of the space age. There are not many mistakes in those stories as Hergé was extremely meticulous when gathering together the necessary documentation. Perhaps the most striking error is when the cartoonist had to rotate (atomic) rocket prior to the Moon landing: he forgot the movement had to be stopped by a jet opposite to the initial one. The Moon explorers have space suits more like the Michelin tires Bibendum character, with transparent helmets. We know today that these should be opaque from the outside for protective reasons, but it is quite natural a cartoonist wants his characters be well identified by his young - and less young - readers. Other Belgian cartoonists have also tackled a few astronomical themes, as, for instance, - André Franquin (1924-1997), probably the most interesting representative of the Marcinelle-Charleroi’s school with his leading characters Spirou and Fantasio, and - Philippe Geluck (1954-), of a more recent generation, with single-drawing cartoons and short strips involving his cat ‘Le Chat’. 4. The OSA Books My talk in Malta started with the presentation of a newly born working group dealing with the socio-dynamics of the astronomy community and aiming at gathering together people who were interested in - studying the astronomy community itself, as much as possible quantitatively, and - studying the interactions of the astronomy community with other disciplines, with amateur astronomers and with the society at large. This project has been progressing well, with already the publication of a volume entitled ‘Organizations and Strategies in Astronomy’ (Heck 2000b) including a presentation of the INSAP conferences (White 2000). A second volume (Heck 2001) is in the making and a third one is already taking shape for publication in 2002. Life permitting, other volumes will be produced subsequently in the same series. People interested in the field should also refer to the on-line bibliography reachable at http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/~heck/sda-pap.htm and continually updated. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Salvatore Serio and to the INSAP III SOC for financial support and for allowing me to say a few words in line with the talk given at INSAP II in Malta. The kind authorization of the Gulbenkian Foundation to reproduce Lépicié’s painting is acknowledged with thanks. Refrerences Al Nath: 1998, L'univers d'Escher, Orion 56/6, 31-32 Al Nath: 1999a, L’éclipse de Perry, Orion 57/5, 22 Al Nath: 1999b, Abelardo Morell et l'oeil de ses lentilles, Orion 57/6, 31-32 Al Nath: 2000a, Le vieil homme et Rigel, Orion 58/1, 30 Al Nath: 2000b, La tour de 300 métres et la coupole du 200 Francs, Orion 58/5, 38-39 Al Nath: 2001, L'exilé de Hauteville House, Orion, in press Heck, A.: 2000a, in Information Handling in Astronomy, Ed. A. Heck, Kluwer Acad. Publ., Dordrecht, pp. vii-x Heck, A. (Ed.): 2000b, Organizations and Strategies in Astronomy, Astrophys. & Sp. Sc. Library 256, Kluwer Acad. Publ., Dordrecht, X + 222 pp. (ISBN 0-7923-6671-9) (see also http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/~heck/sotoc.htm) Heck, A. (Ed.): 2001, Organizations and Strategies in Astronomy II, Astrophys. & Sp. Sc. Library, Kluwer Acad. Publ., Dordrecht, in preparation (see also http://vizier.ustrasbg.fr/~heck/cotoc.htm) Trystam, F.: 1979, Le procès des étoiles, Seghers, Paris, 270 pp. White, R.E.: 2000, in Organizations and Strategies in Astronomy, Ed. A. Heck, Kluwer Acad. Publ., Dordrecht, pp. 203-209