The Anthropology of Adventure

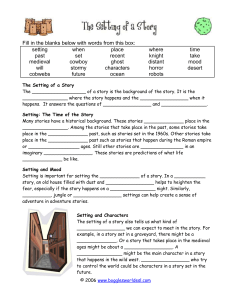

advertisement

ROB—It is my understanding they want a “proposal”—this doesn’t read so much as a proposal, but as a precis/abstract. I wonder if at the beginning here we need to provide a brief description of what we propose, as well as an outline, and then follow up with this more substantive abstract? For example, we could format something like this: The Anthropology of Adventure: Moving Beyond Ambivalence? Proposal for an Annual Reviews of Anthropology Article February 2009 Luis A. Vivanco, Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Vermont and Robert Fletcher… (ROB—order of authorship is totally open; one possibility is to put me as “senior” author, only because I’m (slightly) further along in my career than you and perhaps (again, only slightly) better known; another possibility is to go with alphabetization putting you first; and still another is whoever does the most work. But to be determined only much later…) Overview The proposed article, of approximately …. words (insert average number of AR article words) and …references (insert average number of AR article references here), explores the emprical explosion of popular interest in adventuring, dominant social and cultural theories of adventure, anthropology’s historically ambivalent relationship with adventure, and new directions for anthropological research on adventure. Below is a brief outline and an abstract to give a sense of the substantive issues that would be covered in this article. Brief Outline A. Introduction B. Defining Adventure: What Is It and Why Do People Do It? Overview of dominant theories of adventure C. Anthropology’s Ambivalence with Adventure Historical exploration of anthropology and/as adventure D. Moving Beyond Ambivalence Discussion of new currents in anthropology, as well as future directions Abstract In the past several decades, the practice of adventure has exploded worldwide, as evidenced by dramatic growth and popularization of adventure tourism and “extreme” sports . Consumer culture celebrates the adventurer, producing narratives about both spectacularly successful—and, often more attention-grabbing, spectacularly failed—adventures. It also promotes the consumption of goods meant to capture, or more to the point, generate, a sensibility for adventure, from outdoor magazines to Hummer SUVs. Concurrent with this growth in adventure practice and sensibility has been increasing interest from a variety of academic perspectives to explain this attraction to adventurous activities. Until recently, however, anthropologists have been conspicuously absent from this discussion, which remains dominated by psychologists and marketing researchers. Sociologists are increasingly lending heir voices to the study of adventure as social praxis , although even today anthropologists remain a minority presence. Perhaps this due to an "ambivalence to adventure," which as as Vivanco and Gordon (2003: 11) observe, is related to a longstanding conviction within the field "that science kills adventure, our claims to fieldwork and forms of writing meant to distance us from the self-referential pursuits of adventurers." In Tristes Tropiques, for instance, Lévi-Strauss (1973 [1955]: 17) famously remarked, "Adventure has no place in the anthropologist's profession; it is merely one of those unavoidable drawbacks, which detract from his effective work." Thus, it is possible that, as one contributor to a recent AAA session exploring the anthropology of adventure suggested, that "because it implies a heroic anthropological-fieldworker subject," the "ethnography of adventure" might be seen to "represent an unfeasible (if not immoral and narcissistic) position in a discipline with a high standard of critical reflexivity" (Vivanco and Gordon 2003:11). This situation is unfortunate, we suggest, for anthropologists occupy a unique position in the academic division of labor and can productively contribute to the analyses of adventure in a variety of ways, as we point out below. Indeed, as we also highlight, a number of anthropologists have already furthered discussion of adventure in important ways, and this initial work could be reinforced through subsequent research. In this review, we offer an overview of the rapidly growing literature analyzing adventure, identify anthropologists' own (often ambivalent) contributions to this literature, and suggest new ways in which anthropologists have begun to, through their particular methods (ethnography) and subject matter (cross-cultural comparison), engage with adventure-related research. The growing popularity of adventure is particularly fascinating from an anthropological perspective, because it speaks to many of the central debates in the field, not least of which is anthropology’s own awkward complicity with the category of adventuring, signalled by LeviStrauss above. Adventure may also be described as a form of "deep play" (Abramson and Fletcher 2007) whose stakes are so high that it appears irrational to pursue it. Alternatively, it could reflect an increasingly common sensibility for threat, risk, and danger in contemporary culture (Lianos and Douglas 2000). In either case , the pursuit of adventure might be seen to challenge rational actor and behavior ecological models of human behavior. In addition, analysis of adventure may contribute to understanding changes in the contemporary world often labeled "postmodernism," for the popularity of adventure activities has grown in concert with this shift. Thus, it has been suggested that something about (post)modern society drives people to pursue adventure (see below), and consideration of such dynamics might help to illuminate the postmodern condition (Lyotard 1979, Harvey 1989) as well. Finally, adventure is a key site of cultural production and representation, ranging from the transformation of raw experience through the crafting of particular kinds of narratives, to a capitalist political-economy that views adventure narratives and representations as an avenue for its own expression. We suggest ways in which these and other issues might be explored through future research in our conclusion. Defining Adventure: What Is It and Why Do People Do it? Preceding an analysis of adventure must be an attempt to define the term, a quest that has been the subject of substantial previous research and competing paradigms between the natural and social sciences. The primary idioms of adventure in Western culture are biological, ranging from the biochemical—references to the “adrenaline rush” and “endorphin high” abound—and evolutionary (Vivanco and Gordon ibid.) to the evolutionary. Explanations in this regard have been many and varied. Some suggest that the pursuit of adventure is an element of human nature, conditioned by natural selection for risk-taking behavior during our foraging past (Audrey 1976; Campbell 1968; Manhart 2005). Others have suggested that a quest for adventure is inherent to only some people, who are hardwired to need higher levels of stimulation that the average individual in order to achieve "optimal stimulation." Psychologist Zuckerman's (e.g., 1974, 1979, 2007) well-known "sensation seekers" framework is the most popular explanation in this regard. Continuing this focus on individual traits, some have suggested that adventurers suffer from psychological pathology such as neurosis or addiction (e.g., Farberow, 1980; Huberman, 1968; Ogilvie, 1973). Others describe motivation in terms of the pursuit of valued goals. In this vein, it is commonly pointed out that adventure activities tend to precipitate an altered state of consciousness alternately called "flow" (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), "peak experience" (Maslow, 1961), "edgework" (Lyng, 1990) and "action" (Goffman, 1967). Even while pointing usefully to the connections between human biology and adventure, the reduction of adventure to its evolutionary and biochemical functions and manifestations greatly obscures the social, cultural, political, and economic contexts that shape how and why people think of certain activities and images as adventuresome (Vivanco and Gordon ibid.). In this respect, researchers have suggested that the modern pursuit of adventure embodies a distinctly "dramatic" Western worldview deriving from the ancient Greeks (Propp 1958; Celsi et al. 1993). In the Western drama, a plotline "progresses temporally through periods of tension building to denouement and catharsis" (Celsi et al. 1993:2). An adventure is thus an "episode" (Zweig 1974), an event with "a beginning and an end much sharper than those to be discovered in the other forms of our experiences" (Simmel 1971:188). It "does not move principally from beginning to end, but from peak to peak" (Zweig 1974:191). As a self-contained episode, an adventure usually stands separate in our minds from ordinary life and time (Goffman 1967; Simmel 1971; Zweig 1974; Vester 1987): it is an "extraordinary experience" (Arnould and Price 1993) that "has a sacred function” (Vester 1987:238). Or, as Simmel (1971) observed in his classic essay “The Adventurer,” the functional significance of advenure lies in the contrast it poses to the controlled and expected aspects of quotidian existence. As Zweig (1974:190-1) summarizes the phenomenon, an adventure is a "perpetual leap out of time and continuity into a dreamlike world of risk and violent action." So defined, adventure has been analyzed from a variety of angles, which, for heuristic purposes, we categorize in the typology in Figure 1 and describe further below. Figure 1 (ROB—I’m not sure I totally get this figure’s purpose and meaning) Topic Perspective Method Sports Motivation Interviews Recreation Demographics Marketing research Tourism Structure Textual analysis Journey/Exploration Commercialization Armchair observation Narrative Legal issues Participant observation First, adventure research can be typed in terms of its specific topic. In this respect, most researchers have focused on adventure as a form of sport (e.g., ), while others investigate it as a form of recreation or leisure (Vester 1987; Robinson 1992). Yet others have focused on the classic, grand adventure journeys that defy categorization as travel, recreation, or sport specifically (Noyce 1958). Still others frame the endeavor as a form of tourism (Palmer 2006; Cater 2006), while some analyze it a particular narrative, particularly with respect to its representation in literature (Campbell 1968; Simmel 1968[1911]; Zweig 1973). There is, of course, substantial overlap between these various foci as well. The second fault line in adventure research concerns the particular perspective or dynamic under investigation. Analysis of the structure of the adventure experience has already been described. In addition, a growing body of literature explores the risks, difficulties and potential contradictions involved in the commercialization of adventure, that is, in offering an inherently predictable activity as a touristic experience that can be purchased in advance, a phenomenon that Holyfield (1999) calls "manufacturing adventure" (see also Ortner 1999; Cater 2006; Palmer 2006). Researchers have explored legal issues surrounding the rise of adventure activities as well (Simon 2002). In another vein, researchers have focused on motivation in terms of collective dynamics, viewing the pursuit of adventure as a "performance" in which adventurers act out culturallyvalued "models or scripts" (Celsi, Rose, & Leigh, 1993; Jonas, 1999; Vester, 1987; Gibson, 1996). Finally, a popular line of sociological research describes the pursuit of adventure as a form of escape from or resistance to unsatisfactory aspects of mainstream social life, including "alienation," "overdetermination," "rationalization," "stress," or "boredom" (Arnould, Price, & Otnes, 1999; Celsi, Rose, & Leigh, 1993; Lyng, 1990, 2004; Mitchell, 1983; Vester, 1987; Ridgeway, 1979). Another popular perspective in adventure research has investigated the demographics of adventure practice. Research has made it clear that the majority of adventure athletes and tourists tend to be white, upper-middle-class members of advanced industrial societies, and research has sought to account these dynamics (Fletcher 2008). In this endeavor, researchers have highlighted adventure's embodiment of "neoliberal" virtues such as individualism, competition, and achievement through risk-taking (Kusz, 2004; Simon, 2002, 2004), as well as a "postmodern" emphasis on aesthetic sensation over rational calculation (Stranger, 1999). Others have observed that in modern societies adolescence and early adulthood are typically considered periods suitable for exploration and experimentation, after which individuals receive more societal pressure to "settle down" and "get serious" (see also Dallas, 1995; Gibson, 1996; Gibson & Yiannakis, 2003). Still others have suggested that adventure tends to embody a model of "hegemonic masculinity" in which toughness, aggression, and bravery are considered cardinal virtues (e.g., Kay and Labarge, 2004; Kusz, 2004; Robinson, 2004; Wheaton, 2004b). Researchers have also contended that adventure commonly draws draw on a narrative of colonial adventure and exploration in which white Europeans form the protagonists (Braun, 2003; Coleman, 2002). Finally, it is suggested that the pursuit of adventure may involve the transfer of a professional middle class work ethic, compelling pursuit of continual progress through disciplined labor and deferral of gratification, into the leisure realm (Fletcher 2008) Finally, adventure research varies in terms of its methods. As a field dominated by psychologist and marketing researchers, the majority of adventure research to date has involved interviews, surveys, and other forms of formally structured methodology. In addition, substantial research has involved analyzing texts written by travelers, explorers, journalists, and other adventurers. There has, however, been substantial ethnographic research of adventure as well, undertaken by anthropologists and others. Via long-term participant observation, scholars in a variety of fields have examined such sports as skydiving (Celsi 1993; Celsi et al. 1994; Lyng and Snow 1986; Lyng 1990), hanggliding (Brannigan and McDougall 1983), mountaineering (Mitchell 1983; Thompson 1984), rock climbing (Abramson and Fletcher 2008), whitewater kayaking (Kinney 1997; Fletcher 2005, 2008) and rafting (Arnould and Price 1993; Arnould et al. 1999; Fletcher 2005, 2008; Holyfield 1999; Jonas 1997, 1999), and cliff jumping (Abramson and Laviolette 2007). Anthropology’s Ambivalence with Adventure “Imagine yourself suddenly set down surrounded by your gear, alone on a tropical beach…” (Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western Pacific, p. 1 no its on page 7 or 8) Anthropology has long had an ambivalent romance with adventure. There is little doubt that its public identity is intertwined with it, a fact relevant long before the likes of Indiana Jones came along. Franz Boas himself is reported to have been drawn to anthropology through its association with adventure: growing up in the small Prussian city of Minden, Boas’ favorite books were Robinson Crusoe and Humboldt’s Cosmos, and he practiced eating foods he didn’t like, “In order to accustom myself to deprivations in Africa” (Pierpont 2004:51). Many contemporary anthropologists will admit that it was a similar desire for adventure that attracted them to the discipline, a sensibility very much framed by mass media images produced in magazines like National Geographic or Hollywood spectacles like Lawrence of Arabia. But the association with adventure and adventurers has also been cause for tension within the discipline, as demonstrated by Levi-Strauss’ portentious dismissal of adventuring as the opposite of anthropology’s presumed scientism. Of course, in denial he emphasizes its place, reflecting the contradictions in the discipline’s efforts at differentiating itself from Euroamerican others (missionaries, explorers, traders, administrators, etc.), those figures often present in fieldwork but muted in traditional ethnographic writing and monographs. This is perhaps what makes adventure such an intriguing and productive theme for thinking about and contextualizing the history of anthropology itself, for it means exploring the discipline’s emergence out of the same historical and political contexts that produced colonial-ea adventure-seeking sensibilities and the visual spectacles associated with knowing otherness. It also entails an examination of how the discipline’s own conventions of professional fieldwork and ethical praxis have been shaped in relation to (often in differentiation from) adventurers and adventuresome experiences. Perhaps even more importantly, it can provide a fruitful lens through which to assess the discipline’s changing forms of writing, narration, and representation. Moving Beyond the Ambivalence As anthropologists have begun analyzing adventure as a form of social action and cultural meaning, they have contributed to the various discussions outlined above: 1) While adventure has been described as a universal human inclination, as described above, there has been little cross-cultural research concerning whether something that can be labeled as adventure is actually practiced in societies around the world. Some evidence shows that other peoples, such as Nepalese Sherpas who assist Himalayan mountaineering expeditions, may not actually value climbing as a form of adventure but merely as relatively well-paid work (Ridgeway 1979; Fisher 1990; Ortner 1999), although this view is contested (Thompson 1984). Or consider shamanism, which is intimately connected with the notion of a break with the mundane and an epic and highly hazardous journey (Rubenstein 2006). Can it be conceptualized as adventure? Rubenstein addresses such a question, showing a sharp contrast between Shuar and Western concepts of adventure, and arguing that any understanding of non-Western concepts of adventure must begin with appreciation for very different phenomenological precepts and social practices. There are broader lessons here for a cross-culturally nuanced anthropology of adventure. Indeed, in many parts of the world, including Africa, migrant labor is treated as an adventure (Luig 1996), but the goal is not necessarily self-discovery or self-enrichment. Given that African definitions of the self are not of the autonomous billiard ball variety but rather believe the self to be constructed out of myriad social relations and obligations (Piot 2002), a different version of adventure might be expected. It is suggestive that Rambo is popular in many parts of Africa and the Third World, not because he is a tough adventurer, but because he is seen as fulfilling (pseudo) kinship obligations and fighting an intransigent and corrupt bureaucracy. Thus it is unclear whether the pursuit of adventure—and especially the specific meanings made of it—is actually universal, and anthropological and historical research has begun to shed light on this issue. 2) Similarly, we noted above that, as a form of deep play, the pursuit of adventure seems to challenge rational actor explanations of human behavior, but can such theories recapture this phenomenon. For instance, could adventure be seen as a form of costly signaling (Bird et al. 2000), alerting potential mates to one's possession of desirable qualities of bravery and risktaking, as Manhart (2005) intimates? Can it be demonstrated empirically that adventurous individuals gain reproductive advantage? 3) While a few studies have investigated adventurers' assessment of risk (Lyng 1990; Hunt 1995), more work, drawing on anthropological research concerning assessment of risk crossculturally (e.g., Douglas 1985, 1992; Douglas and Wildavsky 1983), is definitely warranted. One approach would be to investigate, in the tradition of Malinowski (1954) and Gmelch (1992), the pseudo-magical rituals adventurers use to attempt to gain control over inherently unpredictable circumstances. 4) Colonial-era and contemporary adventuring have often been organized around the production and consumption of written and visual narratives, suggesting an exhibitionary logic underlying the conceptualization and practice of adventure. The exhibitionary logic of especially Western advenrturing is one of the central themes of a recent volume Tarzan was an Ecotourist…And Other Tales in the Anthropology of Adventure (Vivanco and Gordon 2006). This volume shows how such themes intersect with long-standing anthropological interest in representation and the political economy of meaning production. 5) Many adventurers describe their activities as ineffable, indescribable, claiming that only someone who has undertaken the experience can truly understand the appeal (Lyng 1990). This is particularly the case with respect to "flow" state of altered consciousness mentioned above (Fletcher 2008). Thus, there appears to important knowledge concerning the adventure experience only accessible via the type of involvement that participant observation affords, and thus anthropologists are uniquely situated to explore this knowledge. 6) And yet there are sources of ongoing ambivalence for anthropologists working on adventure as a subject of study, which have to do with the institutional constraints placed on ethnographic research, as well as shifting notions of ethnographic authority. As Stoll (2006) argues, for example, the rise of institutional review boards regulating ethnographic research are intended to prevent anthropologists and their subjects from entering into risky situations, which explicit ethnographic research on “extreme” sports (for example) might entail. Furthermore, standards of reflexivity in the discipline distrust the credibility of adventure stories and experiences as sources of epistemological authority, especially when they presume the anthropologist as heroic subject.