semantic

advertisement

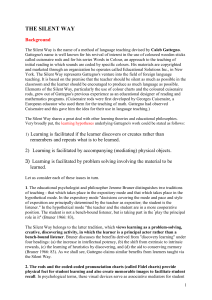

The Silent Way Plus: The Search of a Method and Curriculum I Wayan Sidhakarya The School of International Training, Ubud Rationale of the Silent Way Silent Way is an approach of teaching foreign languages developed by Dr. Caleb Gattegno, which is based on the theory of learning and teaching rather than the theory of language.1 It got its name by the fact that the teacher conducting the class in the Silent Way most of the time is silent. This silence is meant to give the precious time in class for the students to use. The teacher’s presence in class is limited to giving model for the language that the students are going to work on. The assumption is that they bring with them their potentialities and their previous experience of learning their mother tongue. The teacher starts with what the students already have in their mother tongue. A striking feature of any language is its sounds. A lot of these sounds in the students’ mother tongue would be the same with the those of the target language. Using different colors to represent each sound the teacher arouses the students’ awareness of the facts that they can use what they already have in their mother tongue for their new learning. Learning then becomes a conscious effort. The teacher acts just as a model, starting from the known to the unknown. With his/her pointer he points to some particular sounds that the students have already been familiar with to make a word in the target language, or a word may be modeled once while every one in the class pays attention. Since the sounds involved in this word presumably are within their perceptual energy to grasp there would be no problem for them to get. The teacher proceeds from one word to another. Each of these successive words must be meaningful, and meaningful must also be the string of words in the context given. Rods, pictures, objects, or situations are other aids used for presentations in order to connect the sounds and meanings. Especially the use of colored rods is prominent in the silent way teaching practice. The first model presented is for the students to understand the concept of rod. The concept ‘rod’ in whatever language it is represented may have been one of those introduced using fidels.2 The sounds produced are linked with the object within that limited scope provided or made possible by the context of the “here and now”3 activities. Thus, learning becomes an active and direct experience for them. They can see the rod, touch it, smell it and measure it out. They can see truth; a fact that does not yet need a translation for the fact is the whole truth. A one word ‘rod’ aided by the object forms a reality, and triggers meaning. The truth is there when the student develops his own “inner criterion”4 of what is right from within herself, that emerges from her mental power to 1 2 See: Richards and Rodgers 1986, pp. 14-30, and pp. 99-112. Gattegno (1976, pp. 16-17) mentions that the word fidel is an Ethiopian word used for displaying a sound, or in its plural form, fidels, used for displaying “both the totality of sounds of a language and the totality of spellings accorded in each language to those sounds.” 3 As it is used by stevick (1980), p.53. 4 Idem, p. 47. perceive the sound qualities. These sound qualities help the self relate with reality as they are consistent in the words they represent. These words, then, says Gattegno (1976, p. 35) may be retained only if they trigger images, the meanings. The underlying principles for the student’s centeredness in learning are qualities - constitutional traits - that they bring with them. These constitutional traits bear the assumptions that the students have already had some knowledge of their mother tongue inside themselves, with which they start in their learning of the target language. They must be aware that they have within themselves everything that is required for acquiring any language. They can count only on themselves, not anybody else, in producing the sounds. The awareness of being in control leads to independence, initiation, and creativity. Guiding by their intelligence they can choose from the appropriate options available to them in particular circumstances. The decision of making the choice is very crucial as a measure for determining initiativity and creativity as it is triggered by reality. If a student wants to make a tower out of the many color rods available, the choices available for expressing one’s need of rods for building the tower is various. One can say “I need four brown rods and a yellow one, or “I need five rods, four brown ones and one yellow one.” When the student has options from which ones to choose we call that she has autonomy, which we build a long the way in the learning-teaching process. The availability of options creates an atmosphere of flexibility which the student needs for their functioning. An option is selected or not selected becomes the their responsibility, not anybody else. We are responsible for what we choose or not to choose as we have the freedom or the will for doing so. Thus, independence, autonomy, and responsibility become the building blocks of qualities towards freeing the students. In other words we can say that the students are expected to get involved deeply in the learning process with the greatest amount of problem-solving activity. (Richards, 1986, p.100) Thus, learning is not considered as an accumulation of knowledge, rather how to use oneself more effectively. Making mistakes is considered to be normal. The learner is, as Stevick (1980, p. 48) asserts, “supposed to feel that his wrong response (or his right response!) is not being “corrected,” but is being accepted and worked with.” This further gets an assertion from Prator that “No one can learn to communicate in a new language if he is never allowed to make mistakes in it.” (Kenneth 1980, p. 15) Teachers and students have different functions. As mentioned above all works seem to be done by the students. This is true as long as working on the language is concerned. The students are the prime cause for the class to work. They are granted all they have with them, which are relevant to language learning, typically the know-how that they have in their mother tongue. Their function is to work on the language toward acquisition. Meanwhile the teacher is to work on the students, “on what they are doing or not doing, on their progress towards mastery of every item being worked on, and on offering them exercises or suggestions that lead to the required mastery.” (Gattegno, 1976, p.13) Ideally the teacher’s role is multiple in that s/he must participate as a teacher-student while at the same time manipulating the language and observing how each student progresses: again, let the students work on the language and the teacher work on the students so as to understandably put teaching subordinated to learning. (p. 14) The Silent Way Plus 2 While the silence in the part of the teacher and the speaking work in the part of the student conceptually as elaborated above, sound very good, in real classroom situation where, a lot of time, the students’ presence is part of a formal program being sponsored by some institution and the students’ parents it is quite challenging and quite impossible to organize the syllabus procedurally purely in accordance with the Silent Way approach. A lot of time there is a high expectation from their sponsors for them to be able to speak and use the language they are learning as soon as they got to the country where the language is spoken.5 Thus, this good approach of the silent way needs a plus, which the teacher can determine according to what kind of program she is running. Drawing from my own experience in teaching foreign students they are always excited when the teacher can remember their names. Just as the silent way advocates we can start from what the student knows, from the sounds of their mother tongue which they produce effortlessly, we make them aware about that fact. Using the fidels of color charts the teacher aids them through to use that knowledge in the target language, and then the teacher can continue with putting together sounds to make a name word, perhaps, the name of the teacher, such as “WAYAN.” The teacher then points to himself saying his name. Then one student after another does the same thing, saying her own name. From here on we can develop rapidly toward some personal language in a dialogic way. But, rather than following up with a question as ordinarily in a dialog grid, I would follow up - they already know my name by now - with introducing my name in a full sentence, Nama saya Wayan “My name is Wayan.” When they hear the sentence they can make a good guess that the meaning of the sentence could not be far from “My name is Wayan.” After that each student must tell the class her name again in a full sentence. The next step is for them to say Siapa nama anda? “What’s your name?” Each student in the class says this same interrogative sentence, and the teacher would say Nama saya Wayan. “My name is Wayan.” in response to each of them. After that the question and answer must be just among the students themselves. At this point there is no difference in knowledge between the teacher’s and the students’. The students know as much as the teacher does. This exchange model can be repeated for other exchanges like where they stay; where they are from; where they stay in the student’s country of origin. Even negation could be introduced as early as at this time. While in the classroom the teacher must encourage the students to pay attention and use their language resources for initiating learning, absorbing, and acting/reacting to objects or situations available to them. These features bring fort a dimension of life which we call experience. It is not surprising, then, as it is cited by Richard (1986: p, 1001), that Gattegno views language itself “as a substitute for experience, so experience is what gives meaning to language” (Gattegno 1972: 8) Gattegno further asserts that “Language is no more vocabularies to be memorized than structures to be practiced or expressions to be assimilated. It is a functioning of man as wide as he experiences and can express.” (Gattegno 1976, p. 153) If experience what a man is, then, it would be “common sense,” too, to accept the student’s social contact as prima facie in designing the language syllabus. Social factors which the students encounter cannot be ignored. These factors may lead to the 5 In my program, a semester program of the School for International Training’s Study Abroad, in Bali, the students stay with families right from the time they arrive in Bali. So, they expect to learn communicative language from the beginning. reenforcement of the SS’s learning, and they may lead to an even faster acquisition. But it may be also possible that these social forces overburden the student with too much new input as a result of their excitement to being responded. The outside world is not going to ask how many words or expressions s/he has already learnt. Once the language learner produces understandable utterances they could take him/her to the unknown land never traveled before. This kind of thing can overshadow the learning input they got in class as to make it recede to the background and become forgotten, as their retaining system is no longer just reacting to the narrow and invented experience in class, but the truth now has taken a new and wider scope that of involving their daily routines. For that reason in designing the curriculum and/or the syllabus these social factors must be taken into account. Thus, social functioning should be part of the SS functioning in their language learning from the very beginning. This seems to be contradictory to what the Silent Way adheres, in that it considers that “Language is separated from its social context and taught through artificial situations ….. (Richards 1986, p. 101) The use of fidel of color chart and rods and other invented situations in the classroom is very highly artificial, language out of its social context. Natural learning is not being advocated. Yet, I believe that adopting the Silent Way philosophy with the implementation of its techniques for introducing concepts combined with language used in its social context is very rewarding. On one hand, the teacher must put herself in the student’s shoes so, then, she could know experientially that much of language learning is an exploration into another world, yet the unknown is to be discovered by the learners. This is a very student-centered idea. It assumes, as Stevick mentions, that “we know “learning” takes place, and that people can do it, we are much less sure about “teaching.” There can, after all, be “learning” without “teaching.” But one cannot claim to have “taught” unless someone else has learned.” (Stevick 1980: p. 16) He compares the two activities, i.e., teaching and learning, like two men sawing down a tree, “One pulls, and then the other, neither pushes, and neither could work alone, but cutting comes only when the blade is moving toward the learner.” (p. 16) On the other hand, - if we agree that there could be learning without teaching - we must grant our student the social language which would be of immediate use once they go out of the classroom into the real world. We do not want the students to feel that they are wasting their time learning things unrelated to their immediate environment. We as teachers must adjust our dealing with the students and the language. The students’ motivation to interact and communicate must be met, otherwise they will not gain as mush as they would for the time spent in the classroom. In his objection to repetitive drill of the audolingual approach Prator commented that students become bored and “Unless they are encouraged to try to express their real thoughts in the new language they are learning, much of the motivation for studying language is lost. (Ed. Kenneth 1980, pp. 14-15) Again, autonomy in the part the students is a necessity for the language learning to be successful. This is very well-versed by Rivers, “Unless this adventurous spirit is given time to establish itself as a constant attitude, most of what is learned will be stored unused, and we will produce learned individuals who are inhibited and fearful in situation requiring language use.” (Rivers, 1983: p. 48-9) 4 It is of importance to mention here that the type of interaction expected is very high. The teacher must be always in the alert as to how to cope with the immediate needs of the students, as to their styles of learning and their conditions. For this particular reason also my attempt to combine the silent way and the communicative approach gets its justification. One time in the many years of my teaching profession and the many times I use the silent way techniques a student in my class kicked the city we were building using the color rods off. We all kept silent; we did not know what to say. After a while he said that there was nothing adverse in what he had just done, that he was just too tired to think. That incidence just showed me that I was not alert enough to know the student’s condition beforehand. Since that time on I always tell my students my teaching philosophy briefly before starting the program and ask them if they are in a good spirit of doing an activity. Syllabus and Classroom Activities In order to meet the students’ social and/or communicative needs I recommend that, as I mentioned above, the first step be for the students to work on the sound of the language, and second is to work on the language for personal information. Immediately after these two steps numbers and colors, greetings and leave-takings, and the language of daily routines should be introduced. Concepts of numbers and colors are best introduced with rods as are commonly used by the silent way practitioners by first introducing the word balok ‘rod.’ Just as a name is introduced first with a single word leading up to a full sentence, and then to a question answer type of exchange, it is also a nice way to do with the word balok ‘rod,’ leading up to such a sentence as Saya punya dua balok merah. “I have two red rods.” and its interrogative variations. This is a very nice way of spiraling the language, starting from what the students have known, adding new information at a time. The syllabus may be geared toward competency-based activities that help the students dealt with their daily routines such as language used with host family, at the market, in the office, in an interview in order for the students to get some specific information about something or some one. In betweens there are concepts of words, grammars, structures, that need be understood. Here is where the role of the silent way greatly needed. The implementation of the silent way techniques can be webbed in to make the pegs in building the language activities. From the discussion above some of the ways of introducing these concepts should have been clear. Sometimes there are concepts which are difficult to grasp, such as the passive construction, and a lot times language teachers do not border about finding ways of how to have fun with it. Indonesian is one of those languages that uses “passive” as a major strategy in communication. In writing a reading passage or a conversation for the class the teacher may feel that she has to use passive constructions in it for its communicative naturalness. My use of the term “natural” is not in its strictest sense since to be natural must be in the real world rather than in the classroom. So, I would tell the class that we were going to build a city of rods. I would ask four or five volunteers to come up around where the teacher has already placed the box of rods. The teacher gives a model for a construction. Each participant, one after another makes his own building, so that in the end a city is built up. Of course in whatever she does including how many, what size, and what color blocks she chooses is her own. The most important sentence construction each student should say - for the sake of the follow up activity is that the one which says who makes what building and uses what color rods. In other words she is using an active construction, whose “focus” is on the actor. After the city is made, the teacher tells of two of the buildings, one that she herself made and another which was made by one of the participants. The teacher then deliberately tells the existence of that particular building and that building was made/built by some one (the teacher says a name). Modeled by the teacher the participants, one after another, do similar things. We can see that since the focus is on the building the tendency for the construction is passive. 6 References Brown, H. Douglas. 1980. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc. Gattegno, Caleb. 1976. The Common Sense of Teaching foreign Languages. New York: Educational Solution Inc. Gattegno, Shakti. 2000. The Silent way: An Approach that humanizes teaching, Une Education Pour Demain, Association 1901 Prator, Clifford H. 1980. In search of a method. Readings on English as a Second Language: For teachers and teacher trainees, 2nd ed., Kenneth Croft (ed.), 13-25. Boston: Little, Brown and Company (Inc.). Richards, Jack, and T.S. Rodgers. 1986. Approaches and Method in Language Teaching: A description and analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Rivers, Wilga M. 1983. Communicating Naturally in a Second Language: Theory and practice in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Stevick, Earl W. 1980. Teaching Languages: A Way and Ways. Rowly, Massachusetts: Newbury House Publishers. Stevick, Earl. 1982. Teaching and Learning Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.