Alternative techniques in France

advertisement

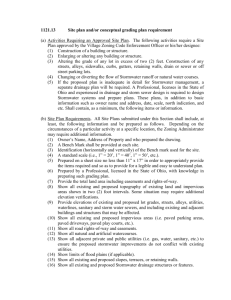

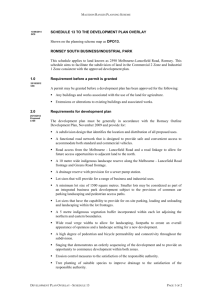

ECOLE NATIONALE DU GENIE RURAL DES EAUX ET DES FORETS ENGREF TECHNICAL SYNTHESIS SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT OF ‘ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES’ IN STORMWATER PURIFICATION MAIGNE Julien e-mail : maigne@engref.fr January 2006 ENGREF Centre de Montpellier B.P.44494 - 34093 MONTPELLIER CEDEX 5 Tél. (33) 4 67 04 71 00 Fax (33) 4 67 04 71 01 SUMMARY KEY WORDS ........................................................................................................................ 2 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 3 ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES IN FRANCE : INVENTORY, STRENGTH AND WEAKNESSES ..................................................................................................................... 3 O O O DEFINITION ................................................................................................................ 3 OVERVIEW OF THE ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES ................................................... 3 KEY STAKEHOLDERS ................................................................................................ 3 JURIDICAL ASPECT : REGULATIONS WHICH CAN BE USED BY THE LOCAL AUTHORITY ......................................................................................................................... 6 BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES : EXAMPLES FROM SOME MUNICIPALITIES IN FRANCE ............................................................................................................................... 7 O O A GLOBAL STORMWATER TREATMENT POLICY ..................................................... 7 THE INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PROCESS.......................................................... 8 Setting a precise goal ..................................................................................................... 8 Compliance control ......................................................................................................... 8 Maintenance ................................................................................................................... 9 Summarized Board ........................................................................................................10 The follow-up work .........................................................................................................10 CONCLUSION .....................................................................................................................11 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................................................................................................................12 1 KEY WORDS Alternative techniques, integrated approach, stormwater treatments, stormwater runoffs, retention, infiltration ABSTRACT French local Authorities have noticed that traditional urban storm drainage systems are often limited when big flows must be purified. As a matter of fact, they have been more and more interested in “alternative techniques” in order to improve drainage systems. However, and whereas the technological issue is no longer a problem, local authorities haven’t strengthened their storm drainage systems management. With both the spreading and the diversification of alternative techniques, stormwater management is becoming increasingly more compulsory. Thus, the way this stormwater management will be set up it will have to incorporate sustainable sanitation. This bibliographical synthesis will present integrated approaches in the management of stormwater discharges, which are built upon strict requirements for new owners and a monitoring strategy. To reach these goals, local authorities rely on computing software or on Geographic Information Systems (GIS). 2 INTRODUCTION As big storms are becoming increasingly frequent, French local authorities have to address the stormwater runoff upon urban impermeable ground issue'. As a result traditional methods in urban storm drainage are changing. Alternative techniques built on softer and more local structures are used more often by the authorities. However, if the technological part is completely mastered, the management of these techniques have not been very well established. The question is how the information from drainage system sites can be collected when several drainage systems are built on private ground ? Moreover what kind of service can be provided for each of them and finally how well will they be monitored ? We will try to answer these questions after a quick view of all the techniques and a brief inventory of the juridical context about stormwater purification. ALTERNATIVE WEAKNESSES o TECHNIQUES IN FRANCE : INVENTORY, STRENGTH AND DEFINITION By « alternative », we will talk about the techniques that remove the traditional feature in urban storm drainage system generalised during the 90’s. Indeed the concept of alternative technique is the counterpart of a “everything in pipes” policy (Chocat and al., Techniques alternatives, 1997). The goal is no longer to send water outside the city through a pipe but to manage it on site or at a river basin level. Two techniques can be used : retention and infiltration. With increasing urbanization, the surface area has become impermeable and it has been necessary to enhance alternative techniques in order to. to stop this trend. When the “everything in pipes” systems are difficult technically or not worth it economically, managing stormwater on site becomes the easiest solution (Maytraud and Brousse, 1998). Alternative techniques offer better integration within the urban development. Because these techniques always present several utilities, they are not seen for their single drainage function. Unlike pipes they need no big excavation works. Consequently they are rather cheaper than classical drainage works. Finally, the cost can be split between the different functions: urban (roadways), landscape (water meadow), environmental (wells) …(Azzout and al., 1994). Nevertheless alternative techniques are often misused because of misunderstanding. In fact, this lack of communication can be explained by the lack of contact between the investors (the city planner) and the users. Very often technical solutions are independent of the city plan (Maytraud and Brousse, 1998). That is why sustainability is a very important issue for the good working order of a drainage system. In the third part of this report we will see the answers given by the local authorities in order to gather city plans and drainage techniques. o OVERVIEW OF THE ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES Alternative techniques can be ordered between two principles : water retention and infiltration in the ground. The following table (cf. table 1) presents the ageing behaviour of each technique. We will see that these techniques need a substantial maintenance work. But some structures are not as sensitive as others are to regular maintenance work. o KEY STAKEHOLDERS 3 Main stakeholders can be divided into two groups : the private and the public. Private can be seen as: - the contracting authority In first place city planners who work on local project, integrated into a global urban development. They are at a key place to promote alternative techniques especially with big city works. At the same time property developers work on a limited area to construct buildings and to sell flats. They may be interested by alternative techniques at a very localized level (infiltration well, stocking roof). However, plot developers who sell land for building don’t work on drainage system. - the project manager Frequently an engineering consultancy takes the project manager's place. They play a key role for the choice of stormwater drainage system technique (Thomazeau and Reysset, 1998). In the public domain, the technical services of the local authority (the municipality or the Intermunicipal Cooperation Public Institution – EPCI –) play the main role. Indeed the Local Urbanism Plan (PLU) is written by the municipality unless the municipality has integrated an Urban Community or an Agglomeration Community (projet de territoire.com, 2005). In the same way, waste water treatment is a municipal skill unless it has been delegated to an upper community (like an EPCI). Consequently, in a local authority, several services can be involved in stormwater treatment even if this topic is not their primary job : the roadway department, the park department …In view of the local authority services, State agents have been instructed to secure urbanism and to give advice and assistance. In view of these stakeholders other players can be found like material makers for technical solutions, public (city walkers for parks for example) … An integrated approach must be planned to take into account so many stakeholders. This approach will have to gather specialists for the same work (Thomazeau and Reysset, 1998). In an article about integrated approach, W. Rauch advocates the need for moving away from solely traditional decisionmaking processes towards a local approach (Rauch and al., 2005). The idea expressed by Brown and Ryan follows that public participation can lead to positive changes in social practices and behaviours (Brown and Ryan, 2001). According to this approach The Grand Lyon project “Porte des Alpes” is a success. A steering committee has lead the different actors towards coordinated work and success in giving a global view to the project. The stormwater drainage has been performed thanks to structures used for many functions (roads, parks, ornamental lakes …) (Sibeud, 2001). 4 Retention Principle General description Alternative Techniques Roof storage Public/Private land private public public and private public and private public and private Cost low 10 to 100 € /m3 (depend of rural or urban area) 100 to 150 € /m2 30 to 70 € /m2 3 € per m2 of drained land Advantage no additional cost compared to a traditional roof Recreational activities possible Low maintenance Technical simplicity rumble absorption No risk of plugging Need low space Need big space Need very specific maintenance (ice removing, plug removing) Additionnal cost compared to a traditional structure Pollution if stagnant water Useless if below a park Flat roof uniquely Disadvantage Description Discussion and cost analysis Maintenance Sources : Infiltration Storage basin (opened with grass) Porous pavement (with Porous pavement Infiltration well permeable structure) (with manholes) Need no extra land control and cleaning Clipping, slope High maintenance : high of the regulation mowing, sweeping pressure sucking up device up the bottom areas processes Need a good knowledge of all technical informations Easy maintenance (Maytraud and Brousse, 1998) - 0.5 € to 1.5 € /m3/year Tricky maintenance (Chocat et al., 1997) 0.5 € à 1.5 € /m3/half year Traditional road maintenance : cleaning the manholes … attractive landscape Need a good soil Ground water pollution Filters cleaning and control of the pouring out system Ditch Water meadow public and private 8 à 18 € per 30 à 40 € /m3 for 3 m of stocked excavation work water public and private attractive landscape attractive landscape Low cost and simplicity No risk of plugging Risk of plugging Need big space Ground water pollution Ground water pollution Anti -plugging control and maintenance Mow the lawn, spray, clean … Regular Regular and Regular Regular maintenance specific maintenance (not maintenance compulsary maintenance - as important as (not as 0.15 € to 1 € /m²/half 0.15 € per m² of wells) - 0.3 € to important as year drained land 0.5 € /m²/year wells) Maintenance frequencies half a year like the rain return period used for the building half a year half a year monthly between 3 to 6 months between 3 to 6 months Lack of maintenance sensibility Low but hydraulic misuses may appear Low But landscape degradations Very High Quick plugging and pourrring out High Quick manholes plugging High Quick plugging Moderate But bordering structures are more sensitive Moderate But bordering structures are more sensitive Azzou et al., 1994 Certu, 1998 Ville de Rennes, 2004 Table 1 : overview of alternative techniques and their time resistance 5 JURIDICAL ASPECT : REGULATIONS WHICH CAN BE USED BY THE LOCAL AUTHORITY Water runoff seems to have no juridical signification (carrefour des collectivités locales, 2004). In fact, it seems that the State didn’t want to regulate on a subject which is part of the Local Authority control. Several ideas have been advanced like a tax on waterproof lands. This idea may be applied in many cities like Rennes (Prenveille, personal communication). As there is not a clear reference to the law, we will have to explore the whole juridical corpus to outline the stormwater treatment policy. Thus we will present the main juridical articles upon the subject. The runoff servitude - art. 640, 641 and 681 from the Civil Code. The 640, 641 and 681 articles of the Civil Code are the major laws that define rights and duties for land owners. The downstream owner has to accept water coming from above. However, if the runoff is modified by human activity (waterproofing, pipes …) the servitude is not applicated. So these articles imply that owners have to maintain the natural water flows. As land is seldom natural, it can be seen as an alternative techniques support to get back a natural behaviour. If people haven’t used yet these articles to sue, it may change as urban flooding increases. Some local authorities state that they will use juridical means to stop the waterproofing trend (Bourgogne, pers. com.). Waterproofing zoning – art 35-III from the 01/03/1992 Water Law This article coming from art. L2224-10 of the Local Authorities General Code, foresees that areas can be established where measures have to be taken to restrict waterproofing and consequently to secure stormwater runoff. This article regulates the way goals will be set up but let the choice of the method to the local authority. The municipality can decide alone whether it will recommend alternative techniques or not (carrefour des collectivités locales, 2004). Natural risks - art R.123-18-II-1 from the Town Planning Code Because of floods, local authorities can impose special conditions to new buildings or urban structures (it will be written in the PLU). Planning permission - art 421-3 from the Town Planning Code This article states that planning permission can be denied if the projected building doesn’t respect water drainage regulations. This article is a main tool to lay down principles written in other local town planning documents like the PLU, drainage rules, health rules …(CERTU, 1998). Although it is stated in many different and scattered regulations, the law is coherent toward more restriction against waterproofing and more power for local authorities. This supports the use of alternative techniques. 6 BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES : EXAMPLES FROM SOME MUNICIPALITIES IN FRANCE o A GLOBAL STORMWATER TREATMENT POLICY As said previously, regulations support alternative techniques initiatives and a global view seems compulsory in order to gather together so many actors. Natural short-term and low cost thinking lead to disconnected work between town planning and technical choices that will affect project effectiveness. Indeed alternative techniques can not be seen just as a technical choice but as an alternative to a traditional drainage scheme. Maytraud and Brousse (Maytraud, Brousse, 1998) prefer the “alternative approach” term to stress the global dimension. A global approach is all the more significant as a non-coordinated network can have the opposite effect. Runoff may increase without any stormwater treatments. So at a river basin level, many non-coordinated structures have a negative action against floods (Azzout and al., 1994). Similarly, none of the solutions are effective in all cases and a longer and more appropriate thinking has to be promoted. For instance retention should be avoided downstream where the main problem is to drain off big rain discharges coming later from the top. This global stormwater treatment policy can be written into a sewerage master plan. This plan has to explain which place will be attributed to both traditional and alternative techniques in a larger drainage context. That’s why information on these two techniques must be collected and be available for teams in charge of the drainage mission. Many documents can link together stakeholders especially people from the private and public circles. The next figure summarizes the main steps during a building project. Each step represents a good opportunity to bring private and public circles closer (Thomazeau and Reysset, 1998). Public Private Sewerage regulation (in the PLU appendix) Notarial deeds and servitudes Specifications Planning permission Contrat-based maintenance Agreement End of work compliance Temporary maintenance Final maintenance Handover to the authorities Figure 1 : Different steps during the public/private consultation Following this figure very few documents are used by the authorities to regulate building works even if there are plenty of juridical references. Thus the ‘sewerage regulation’ is the major document for them to edify the rules whereas the ‘planning permission’ becomes the last control point. Authorities can consult and check each step of this proceeding. 7 o THE INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PROCESS Setting a precise goal For more effectiveness, all lands have to be treated in the sewerage master plan without any exceptions. For each plot, the municipalities interviewed for this report, have set a detailed goal to limit surface waterproofing. On the one hand the Douai Authorities set the goal individually depending on land features (Hérin, pers. com.). On the other hand Toulouse, Bordeaux and Rennes have preferred to lay down restrictive impermeable coefficients on their territory divided into two or three areas. Questions have been raised about the large variety in impermeable coefficients or the runoffs admissible flows. Therefore it’s a 1 litre per second and per hectare flow chosen in Paris, whereas it reaches 7 L/s/ha in Nimes and Montpellier or 3 L/s/ha in Bordeaux (Baladès, pers. com., Desbordes, pers. com. and Espinasse, pers. com.). So it seems that these coefficients are empirically set and are useless for avoiding the waterproofing processes (Bouillon, pers. com.). For instance, the 3 L/s/ha parameter often used in France, comes from a thoroughly different context taken in a Dutch study. Besides, it is hardly possible to measure such little flows because of difficult rainy conditions (Desbordes, pers. com.). These coefficients are less used to monitor waterproofing than to give a common reference for retention work (like a storage basin or any stocking structure). The flow rates inferred from these coefficients will be very useful to fix pipe sizes, pump capacities etc. Finally with some criterion, municipalities can give some clear and easy recommendation for builders (Baladès and al., 2001). Furthermore these flow rates must be linked to rain intensity : the rain return period. Very often it is a 10-year period but sometimes nothing is detailed and as a result it increases imprecision. Finally, as it is very difficult to identify the natural flow rate, can a very low flow rate be convincing ? Indeed, water can’t infiltrate more than it would have be naturally (Savary, pers. com.). Setting the flow rate is a very important step during the stormwater treatment policy. For instance, the Agricultural and Forest Departmental Service of the Gard Department according to DIREN advise 100 L/m² criteria for retention and a 7 L/s/ha limit for the flow rate. This choice should allow the surface to go back to a natural soil behaviour (Espinasse, pers. com.) Compliance control The authorities have to monitor each building project if they want the regulations to be respected. Planning permission delivery is a key-step for better control. In Douai, a specific municipality service studies closely every request from a sewerage point of view. If needed they can ask for more information or technical modification e.g they might ask for technical alternative solutions. Thanks to their local skills, this service is in charge of the tricky work of determining if the new project will deepen the stormwater runoff (Hérin, pers. com.). Local knowledge is indeed necessary. In Rennes infiltration is forbidden because of an unsuitable waterproofed soil. The Municipality promotes retention structures by calculating for each project the minimum retention volume needed (Prenveille, pers. com.). In the same way, other cities use compliance control to assess if the contracting authority have respected all the specifications. Nevertheless, local authorities never impose the technological choice. Contracting authority is free to choose its own method (Baladès, com. pers.) 8 Maintenance However even if the compliance control has been delivered, strict monitoring must be set up to secure a workable structure and at least constant waterproofing. Two cases can be considered : Public plots The structure maintenance is in the charge of the local authority. As alternative techniques assume many functions, maintenance is realised by the service that maintained the primarily function. For instance water meadows or ditches are maintained by the park services, porous pavements by the urban facilities service. Private plots For private structures, maintenance is in the charge of owners. In big housing developments, owners may gather to ask firms to carry out maintenance for their own. As maintenance is done by private actors, local authorities can propose a contract to get back structures. Nowadays handover is not automatic but is becoming more and more common (for porous roads and ditches especially). It seems that owners are rather happy to give up this seemingly tedious task (Hérin, pers. com.) Handover is impossible for small structures like infiltration wells or roof storage and therefore maintenance is always private. Improving sustainable stormwater drainage would need a follow-up visit to secure good working order. Nevertheless in France local inspectors are not allowed to enter private lands for drainage control. Therefore in Douai these controls are done during the sanitary control planned by local rules (they look for waste water discharge, savage plugging …) (Hérin, pers. com.) Other policies should be considered. The Bordeaux Urban Community doesn’t want to monitor maintenance that has to be realized by owners but states that owners can be sued if unusual floods or even runoff is noticed. Local authorities press downstream owners to sue upstream owners according to the Civil Code (cf. Table 2). Just as previously, the Municipality will complain to the Court if it notices discharges in its waste water network (Baladès, pers. com.). The Great Toulouse has the same approach hoping that the fine system will prevent offenders (Artero, pers. com.). To conclude, we can notice some similarities between local sanitation authorities that might inspire us. Indeed authorities work hard to press owners to regularly clean their septic tanks. Today some associations can be found which maintain the whole local sanitation sytem at low prices. These associations subsidized by local authorities are an easy way to reintroduce regular maintenance in private houses : which provide a lot of social benefit (Desbordes, pers. com.). This example might inspire stormwater drainage managers in the near future. In Douai an association has been already created to promote alternative techniques : the « Association Douaisienne pour la Promotion de Techniques Alternatives » (ADOPTA, 2000). Finally perhaps this association will sooner be able to assume the maintenance service. 9 Summarized Board Bordeaux Urban Toulouse Douai Rennes Community Agglomeration Agglomeration Agglomeration Stormwater drainage management documents yes. Steered on Stormwater the big building planned for 2006 not planned yes master plan works city planner Other Sewerage document, PLU, management PLU regulation, zoning PLU, zoning plan Sewerage plan plan regulation Management think about a data GIS under GIS tools base or a GIS development Main goals 30 % to 55 % on 90 % in the center 33 % in Toulouse Impermeable the whole territory 40 % elsewhere no coefficient 20 % elsewhere (3) (1) (4) Admissible flow rate Maintenance and Monitoring services Private to Public Handover Technical monitoring Pivate land policy 3 L/s/ha non no 13 L/s/ha to 110 L/s/ha Administration services management Executive service Executive service for the planning Executive service Project manager for the planning permission. for the planning service and permission. Sanitation permission operating service Sanitation service service, parks service ... Maintenance and Monitoring policy possible if possible if tecnical tecnical and possible with a possible with a and administrative administrative regular regular requirements are requirements are maintenance maintenance respected respected formalization yes - sanitation no but maybe in a under no service next future development (2) Legal action if they noticed abuses Deterrent fines Follow-up visits Legal action will press owners for both a sanitary The Municipality to maintain and a preventmight launch a structures flooding goals waterproofing tax (1) (Miquel, 2003) and (Communauté Urbaine de Bordeaux, 2005) (Bourgogne, pers. com.) (3) (Communauté d'Agglomération du Grand Toulouse, 2002) (4) (Prenveille, 2000) and (Prenveille, pers. com.) (2) Table 2 : General presentation of stormwater policies in few French big cities The follow-up work Knowing exactly the location and state of alternative techniques will be a major task for local authority before it starts with the main drainage works. The more decentralized structures are the more it needs alternative techniques. So after planning permission, local authorities will have to manage a data base system to keep at a local level the knowledge of the drainage 10 solutions. Conversely the Bordeaux Community with only 44 storage basins doesn’t need complex follow-up work. These structures are very well known by the technical services of the City. (Baladès, pers. com.). The Douai Agglomeration, with more than 1 000 alternative techniques, developed the Geographic Information System (GIS) for the stormwater drainage features. This step for more integrated management has been realised gradually as GIS is not yet a major tool in technical services. Therefore P. Gourmain (Gourmain, 2001) said that more than 70% of municipal data are in fact localized data. As a matter of fact, GIS is fully useful in alternative techniques management. In this case, the three main functions are : - the spatial data base function : to store all the main features of the techniques (size, achievement year …) and to localize it. - the graphic function : to generate maps and action plans. - the analysis function : to reference information and to plan inspections (date and place) The Douai Agglomeration gets all the main features of their decentralised drainage structures. They are currently thinking of a recalling system for inspection planning (Hérin, pers. com.). CONCLUSION According to this French overview, it seems that few local authorities have chosen an integrated approach for urban storm drainage. This bibliographic synthesis noticed two main barriers towards a more integrated approach : the acceptable runoff assessment is still unclear and it will distort behaviours if the goal achievement can’t be checked. The second challenge for the authorities will be their ability to control the good working order of various and decentralized structures. The Singapore experience illustrates very well the planning and control linkage. After the violent storms of 1972, a Drainage Department was set up at a national level to implement drainage planning and control strategies for flood alleviation and prevention. At a local level, this program is implemented by a “catchment team “responsible for one of the eleven drainage administrative catchments. By means of a local drainage plan, the catchment team identifies and implements new drainage schemes and maintains drainage records (Meng Check, 1997). For a small country (580 km² for the main island whereas the Great Lyon is a 500 km² territory), this approach succeeded in linking together two scales of management : - globally to set up goals and to control the effectiveness - locally to promote more suitable techniques 11 BIBLIOGRAPHY Association Douaisienne pour la Promotion de Techniques Alternatives, [08/21/2000 updating], Présentation. ADOPTA, Douai. Available on the Internet : http://adopta.free.fr/accueil.htm (checked the 5 of déc. 2005) Artero Roger, engineer from the Great Toulouse sewerage service, phone call, 11/07/2005. Azzou Y., Alfakih E., Barraud S., Cres F-N., 1994. Techniques alternatives en assainissement pluvial. Choix, conception, réalisation et entretien. Ed. Tec et Doc, Lavoisier. Paris. 371 pages. Baladès J-D., Berga P., Cuartero J., Ruperd Y., 2001. Démarche intégrée pour un zonage d’assainissement pluvial et la révision d’un Plan d’Occupation des Sols. Novatech’2001, Villeurbanne, 25-27/06/2001. GRAIE, Villeurbanne. Baladès Jean-Daniel, engineer from the South West CETE, phone call, 10/28/2005 Bouillon Henri, engineer from CERTU, phone call, 11/07/2005. Bourgogne Pierre, Water service director from the Bordeaux Urban Community, electronic mail, 11/23/2005 Brown R., Ryan R., 2001. Evaluation of the storm-water management planning process. Environment Protection Authority (EPA). 2000-88, Sydney. Disponible sur Internet : http://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/resources/usped.pdf (checked the 5 of déc. 2005) Carrefour des collectivités locales, Nov. 2004, Régime juridique des eaux pluviales. Available on the Internet : http://www.carrefourlocal.org/vie_locale/cas_pratiques/environnement/eaux.html (checked the 5 of déc. 2005) CERTU, 1998. Techniques alternatives aux réseaux d’assainissement pluvial. Ministère de l’Equipement, des Transports et des Logements, Paris, 155 p. Chocat B. et al., 1997. Chaussée à structure réservoir In: Encyclopédie de l’Hydrologie Urbaine et de l’Assainissement. Ed. Tec et Doc, Lavoisier. Paris. pp 185-199. Chocat B. et al., 1997. Techniques alternatives In: Encyclopédie de l’Hydrologie Urbaine et de l’Assainissement. Ed. Tec et Doc, Lavoisier. Paris. pp 968-979. Communauté d’Agglomération du Grand Toulouse, règlement d’assainissement, 28/06/2002. Règlement d’assainissement, 17p. Available on the Internet : http://www.grandtoulouse.org/admin/upload/document/30-reglement_assainissement.pdf (checked the 5 of déc. 2005) Communauté Urbaine de Bordeaux, 07/01/2005. Règlement du PLU, 288 p. Available on the Internet : http://www.lacub.fr/projets/plu/Fichiers/reglement/PLU-reglement-arrete-070105.pdf (checked the 5 of déc. 2005) Desbordes Michel, Montpellier II University Professor, phone call, 11/14/2005. Espinasse Michel, engineer from the Water and Environment Service of the Direction Départementale de l’Agriculture et de la Foret du Gard, phone call, 01/05/2006 12 Gourmain P., 2001. Intérêts et coûts des Systèmes d’Information Géographique dans la gestion des services d’eau. Synthèse technique. ENGREF, Montpellier. Oieau, Limoges, 14p. Hérin Jean-Jacques, Technical services General Director of the Douai Agglomeration, phone call, 11/14/2005. Maytraud T., Brousse G., 1998. L’eau et l’urbanisme, comment ça marche ?, Techniques Sciences Méthodes, n°4, avril 1998, pp 57-64. Meng Check L., 1997. Drainage Planning and Control in the Urban Environment. The Singapour Experience, Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, n°44, 1997, pp 183-197. Miquel G., 2003. Rapport sur la qualité de l’eau et de l’assainissement en France. Office Parlementaire d’évaluation des choix scientifiques et technologiques, Paris, 195 p. Available on the Internet : http://www.senat.fr/rap/l02-215-1/l02-215-11.pdf Prenveille A., 2000. Assainissement pluvial urbain. Présentation de la démarche globale réalisée par la ville de Rennes pour assurer la maîtrise de l’imperméabilisation des sols, Bulletin des laboratoires des Ponts et Chaussées, n°224, janv-fev 2000, pp 87-96. Prenveille Alain, Urban sewerage Head of service of the Rennes Municipality, phone call, 11/29/2005. Projet de territoire.com, [updated in 2003], La communauté urbaine : présentation synthétique. Available on the Internet : http://www.projetdeterritoire.com/spip/article.php3?id_article=471 (checked the 13 of dec. 2005) Rauch W., Seggelke K., Brown R., Krebs P., 2005. Integrated Approaches in Urban Storm Drainage : Where do we stand ?, The Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 35, n°4, pp 396-409. Savary Patrick, engineer from Etudes Conseils Eau, interview of the 12/12/2005. Sibeud E., 2001. Lyon – Porte des Alpes. La mise en œuvre de techniques alternatives intégrées dans une démarche de développement durable. Novatech’2001, Villeurbanne, 2527/06/2001. GRAIE, Villeurbanne. Thomazeau R., Reysset P., 1998. Les acteurs de l’aménagement urbain et la gestion des eaux pluviales, Techniques Sciences Méthodes, n°4, avril 1998, pp 65-69. Ville de Rennes, 2004, working document, développement durable : pour une gestion douce des eaux pluviales, 26 pages. 13