ANSELM`S SECOND ARGUMENT - NORMAL MALCOLM`s VERSION

advertisement

Dialogue Education

THE ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT

for the existence of God

********************************************

There are a number of ways of trying to prove that God exists. One can:

1. Argue from the design in the world (The DESIGN ARGUMENT)

2. Argue from the existence of an absolute standard of morality or from the existence of our

conscience (The MORAL ARGUMENT)

3. Argue from existence of the world based on the first cause argument or the dependency of the

world on God (The COSMOLOGICAL ARGUMENT)

4. Argue from human experience of God (The ARGUMENT FROM RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE)

All these arguments are important and significant but they share one thing in common - their starting points

are something we experience. They are A POSTERIORI ARGUMENTS in that they are based on experience

as a starting point. The arguments may or may not succeed, but at least it would make sense with all of them

to deny the existence of God, to say that perhaps God does not exist. After all, it is a possibility that Tony

Blair may not exist even though he does - it is not necessary that Tony Blair exists. He might not have done.

The Ontological argument is totally different from any of the other arguments on several grounds:

1.

2.

3.

It does not start from experience as a starting point,

It claims to arrive at the existence of God by analyzing the idea of God and this idea does not

depend on experience - it is therefore an A PRIORI ARGUMENT.

If the argument succeeds, then the existence of God is logically necessary and, as a matter of logic,

it simply does not make sense to doubt that God exists.

The key issue in the ontological argument is what is meant by 'necessity'. Once you have understood

this you will have begun to understand the argument - if you fail to understand this you will not have begun

to appreciate what the argument is about.

Take this issue slowly and start by moving back a little. Take the statement: "All bears are animals" This

statement is true, but what makes it true? It is true because we know by examining or analysing the word

'bear' that it must be an animal. It is part of the very definition of the word bear that it should be an

animal. It simply does not make sense to say that a bear is not an animal. Once we understand what the word

'bear' means we can see that various statements are true including:

"All bears will die", and

"Bears have bones"

It will be clear from this that when we are talking here about bears we are referring not to Paddington

bear, Rupert Bear, Pooh bear or even Teddy bears but to bears that are animals, that are born and die and

that have sense organs. I am defining what a bear is and the truth of the statement follows from my

1

Dialogue Education

definition. If I want to determine the truth of these statements I first have to understand what is meant

by the word 'bear'.

Now take another statement:

"All bears are brown"

This is different from the previous statement not just because it is not true (we know that there are black

bears and polar bears) but because the statement could only be proved to be right or wrong based on

EVIDENCE. We would have to check all the bears we could find to find whether they were all brown and if

we found one black or white or red bear the statement would be untrue.

So we have a division between two types of statement:

1.

ANALYTIC STATEMENTS are statements which are necessarily true because the predicate is

included in the subject. To determine their truth, we have to learn more about what the subject

word means. So to determine whether 'All bears are animals' is true, we would have to find out how

the word 'bear' is defined.

2. SYNTHETIC STATEMENTS are statements which are true because of the evidence. We will not

find out whether the statements are true by analysing the subject but by looking at evidence.

ANALYTIC statements are A PRIORI because these are independent of experience whilst SYNTHETIC

statements are almost always A POSTERIORI (the 'almost' here is because Kant maintained there were a

priori synthetic statements - but these are not relevant for the Ontological argument). What has all this to

do with God? The answer is a great deal. The key problem is whether the statement: GOD EXISTS is an

analytic or synthetic statement. It is this question with which the ontological argument is, at least partly,

concerned.

Aquinas maintained that as far as we are concerned 'God exists' is a synthetic statement - if we want to

determine whether it is true we must start from facts in the world, we must reason from experience and

start with the existence of motion, causation, contingency; the design in the world or similar features of the

world around us. It makes sense to say that 'There is no God' just as it makes sense to say 'there are no

bears'. Both statements would be based on evidence and both statements may or may not be true. Aquinas

did not think it was possible for human beings to know God's essence. If we could know God's essence, then

he considered that we would be able to know that God's essence includes God's existence, but we cannot

know this. The ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT maintains that 'God exists' is an ANALYTIC STATEMENT. It

cannot fail to be true. If this is the case, then to determine whether the statement is true we must first

begin with a definition of God. AQUINAS maintains that GIVEN that the world is caused, is in motion or is

dependent then IT IS NECESSARY that God exists. God is DE RE necessary, God is factually necessary

without dependence and without beginning or end, God is necessary in himself but, Aquinas holds, we can only

know that God is necessary by examining the world around us. It makes sense to deny that God exists even

though such a denial would be false. (As we saw in the Cosmological argument, some maintain that the very

idea of de re necessary existence is flawed. Whether it is or not is a crucial issue for the Cosmological

argument.)

THE ONTOLOGICAL ARGUMENT effectively starts with the claim that God is DE DICTO

NECESSARY. God cannot not exist - it is logical nonsense to say that God does not exist since once

2

Dialogue Education

we have understood what the word God means we could not fail to see that God exists in just the same way

as once we have understood what a bear is we could not fail to understand that it is an animal. However it

seeks to move from God's de dicto necessity to God's de re necessity - AND THIS IS WHERE PROBLEMS

ARISE.

This, then, is where the whole debate starts. If you think that it is odd that no mention has yet been made

of Anselm, Gaunilo, Descartes, Gessendi, Leibniz, Hume, Kant, Hartshorne and all those other people who

have discussed the argument, then this is because none of them will really be understandable until one has

understood that the ontological argument is an a priori argument which is held to show that God's existence

is de dicto necessary and that this can then be used to arrive at God's de re necessary existence. If this is

accepted, then everything is going to hinge on how you define God.

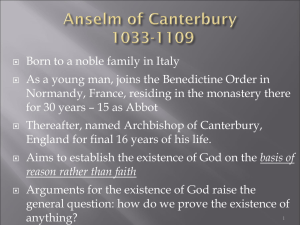

ANSELM’S FIRST ARGUMENT

------------------------If everything is going to turn on definitions, it is not surprising that Anselm's argument starts with a

definition. Anselm defines God as:

"That than which nothing greater can be conceived"

Notice that this definition is given in the Proslogion (1078) Ch. 2, which is an address to God - Anselm is

trying to show how self-evident God's existence is to a believer1. Anselm believes already and this is

important. The Proslogion is, effectively, a prayer and not a piece of philosophy and this is important.

Anselm's argument proceeds as follows:

-

God is by definition that than which nothing greater can be conceived.

This definition is

understood by believers and non-believers.

It is one thing to exist in the mind alone and another to exist both in the mind and in reality.

It is greater to exist in the mind and in reality than to exist in the mind alone.

Therefore God must exist in reality as well as in the mind. If he did not, then we could conceive

of one who did and he would be greater than God.

In effect, what Anselm is saying is that 'God Exists' is an analytic statement - we can find that the

statement is true merely by analysing what it means to be God. The key step is (3) above - the move

from God's existence as a concept to God's existence 'in re', in reality. Anselm was a Platonist (unlike

Aquinas who was an Aristotelian) and this had a major effect on their positions - as should become clear

from the reading.

1

Anselm’s first argument (in Proslogion Ch.11 runs as follows: ‘Well then, Lord, You who give understanding in faith, grant me

that I may understand, as much as you see fit, that You exist as we believe You to exist, and that You are what we believe You to be. Now

we believe that You are something than which nothing greater can be thought. Or can it be that a thing of such a nature does not exist,

since ‘The Fool has said in his heart that there is no God’ (Ps. 13, 1; 52, 1)? But surely, when this same Fool hears which I am speaking

about, namely ‘something-than-which-nothing-greater-can-be-thought’ he understands when he hears, and what he understands is in his

mind, even if he does not understand that it actually exists. For it is one thing for an object to exist in the mind, and another thing to

understand that an object actually exists. ... Even the Fool, then, is forced to agree that something-than-which-nothing-greater-cannotbe-thought exists in the mind, since he understands this when he hears it, and whatever is understood is in the mind. And surely thatthan-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought exists in the mind since he understands this when he hears it, and whatever is understood is in

the mind. And surely that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought cannot exist in the mind alone. For if it exists solely in the mind, it

can be thought to exist in reality also, which is greater. If, then, that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought exists in the mind alone,

this same that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought is that-than-which-a-greater-can-be-thought, But this is obviously impossible.

Therefore there is absolutely no doubt that something-than-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought exists both in the mind and in reality.

3

Dialogue Education

Gaunilo challenged Anselm with his LOST ISLAND argument. If the Lost Island is the greatest that can be

conceived it too must exist. Gaunilo, however, did not really understand Anselm's challenge. Anselm's point

is that only God has all perfections and his argument therefore only applies to God, only God is 'that than

which none greater can be conceived', only God is the greatest possible being. Because God is perfect God

must, for Anselm, be necessary as otherwise God would lack something that belongs to perfection (although

it may be asked what characteristics belong to perfection and this may not be clear).

Plantinga says that the concept of the 'most excellent island' is as meaningless as 'the highest number' as

the qualities that make up an island's excellence have no intrinsic maximum. This can lead one to ask

whether the same applies to God - Anselm's reply to Gaunilo effectively says that it does not.

Gaunilo is saying that God is merely the greatest ACTUAL being just as the island is the greatest ACTUAL

island - but this is NOT what Anselm is saying. Anselm is claiming that God is the greatest POSSIBLE being

and his argument only applies to God.

St. THOMAS AQUINAS (1224-75)

----------------------------St. Thomas Aquinas rejects the Ontological argument for various reasons:

Aquinas claims that we do NOT have an agreed definition of God. He rejects Anselm's definition and holds

that many people have different ideas of God - some people even hold that God has a body (which Aquinas

considers to be absurd). We cannot, therefore, start from an agreed definition since not only can we not

agree on a definition but even if we could we have no way of knowing that this definition is correct.

We can only reason to God from the effects of God’s action in the world - so any argument has to start

from experience. It has to be A POSTERIORI.

Aquinas does not consider that we know what God’s nature is, so a real understanding of God’s nature is

impossible to us. However Aquinas holds that IF we understood God’s nature (as God does) then we would

know that God’s nature DOES have to include existence (i.e. ‘God exists’ would be analytic) but as we do

NOT know God’s nature, we have to treat it as synthetic. BE CAREFUL HERE THEREFORE. Aquinas is saying

that, in fact, ‘God exists’ is analytically true but we cannot know this to be the case and we can only treat it

as synthetically true.

RENE DESCARTES (1596-1650)

-------------------------Descartes' version of the argument is in some ways clearer than that of Anselm. Descartes holds that just

as we cannot conceive of a triangle without it having three angles; just as we cannot think of a mountain

without a valley so we cannot think of God without conceiving him as existing. Descartes gave several more

precise formulations of his argument in response to the criticism of Caterus. His second restatement is as

follows:

1. Whatever is of the essence of something must be affirmed of it

2. It is of the essence of God that he exists for by definition his essence is to exist, therefore

3. Existence must be affirmed of God.

Descartes did qualify his argument in order to guard against the sort of attack that Gaunilo developed

against Anselm. He says that:

4

Dialogue Education

1.

The argument applies only to an absolutely perfect and necessary being (it cannot, therefore, be

applied to something like a lost island).

2. Not everyone has to think of God, but if they do think of God then God cannot be thought not to

exist.

3. God alone is the being whose essence entails God’s existence. There cannot be two or more such

beings.

Aquinas rejects precisely the point that Descartes wants to affirm. Descartes says we can know God's

essence and therefore we can say that God must exist. Aquinas does not think that God's essence is

knowable to us.

In a way Descartes is right - It is impossible to have a triangle without it having three angles, just as it is

impossible to have a spinster who is not female - the predicates follow from the subjects. BUT all this tells

us is something about the IDEA of a triangle and not about whether there are any triangles. We might say

that "It is necessary for a unicorn to have a horn" and this may indeed be true, but this does not prove

there are any unicorns.

ONCE YOU HAVE UNDERSTOOD WHAT A TRIANGLE IS, THEN YOU WILL SEE THAT A TRIANGLE

MUST HAVE THREE ANGLES, similarly ONCE YOU HAVE UNDERSTOOD WHAT IT MEANS TO TALK OF

GOD, THEN GOD MUST EXIST. The issue, however, is what is meant by existence.

IMMANUEL KANT (1724-1804)

-------------------------It was Kant who called this the ‘ontological argument’ - the reason for the name is that he thought that the

argument made an illegitimate jump from ideas to reality (‘ontos’). Kant held there were various objections

to the argument:

We have no clear idea of a necessary being - God is defined largely in negative rather than in positive terms.

The only sort of necessity is where statements are necessary because of the way words and language are

used. It applies to propositions, not to reality. There are NO necessary propositions about existence.

What is logically possible may not be ontologically possible. It is true that a triangle must have three sides

or a unicorn must have a horn but this does not mean there are any triangles or any unicorns.

Existence is not a predicate or a perfection.

Kant’s last point can be summarised as follows:

1. Whatever adds nothing to the concept of an essence is not part of that essence,

2. Existence adds nothing to the concept of an essence - to say a hundred dollars is real rather than

imaginary does not add any characteristics to a dollar.

3. Existence is not part of the essence of a thing, it is not a perfection.

Kant considered that Anselm’s argument can be summed up as follows:

1. An absolutely perfect being must have all possible perfections,

2. Existence is a possible perfection

3. Therefore an absolutely perfect being must have existence as one of its perfections.

5

Dialogue Education

Kant rejects (2). One can have an idea of something, but however much you develop the idea, you have to go

outside it by getting evidence from experience as to whether or not it exists.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO SAY THAT GOD EXISTS?

-------------------------------------------This seems simple enough doesn't it? However it is NOT simple and most of the confusion about the

Ontological argument revolves around a confusion on this point.

Is God's existence more like a bear or a triangle? Is God an object of some sort? If God is an object, then

he is rather like a bear - there may be a bear in the road outside or there may not (cf Martin Lee's article either God is something or nothing. To say he is like a bear is to say God is a 'something', however ineffable)

similarly there may be a God or there may not be. Hume and Kant both thought that God's existence was

like this. God is in some sense an object, a being of some sort - albeit a highly exalted being. If this is so,

then both Hume and Kant held we cannot move from the IDEA of God to the reality of God. I may have a

perfectly clear idea of a bear but this does not mean there is one.

Hume says that however much our concept of an object may contain, we must go outside it to

determine whether or not it exists. We cannot define something into existence - even if it has all the

perfections we can imagine. As Kant says "Existence is not a perfection, but that in the absence of which

there are no perfections.". Kant is saying that existence is not a predicate: ‘all existential statements are

synthetic’ - in other words, any statement to the effect that something exists may be true or it may not, it

needs evidence to support it. As Kant says, to posit a triangle, and yet to reject its three angles, is selfcontradictory; but there is no contradiction in rejecting the triangle together with its three angles. The

same holds true of the concept of an absolutely necessary being.

Bertrand Russell argues that when we say 'Cows exist' what we are really saying is that the concept of

'cow' is instantiated whereas the concept of unicorn is not. In this, Russell follows Frege who argues that

'exists' tells us that a particular thing is instantiated or exists rather than being a predicate. To say that

something exists is to say that the collection of features indicated by the predicate expression of that

thing is realized or instantiated. Frege’s famous example is:

‘Tame tigers exist’

‘Exists’ here is not a predicate, it adds nothing to our knowledge of tigers. All it is saying is that the concept

of ‘tame tigers’ is instantiated - i.e. there are tame tigers. By contrast:

‘Tame tigers eat a lot’

does tell us something about tame tigers - ‘eat a lot’ does, therefore, function as a predicate.

If God is in some sense an 'object', a something, even if a timeless and spaceless substance, then Aquinas is

right - the ontological argument gets us nowhere. Aquinas did not think that God was an object in any sense

like the way we normally use the term - God is not in space or time. Nevertheless, the word God refers

successfully to the God who exists beyond space and time and on whom the whole of the created order

depends. This God may or may not exist, but we cannot prove His existence from analysing his nature which

is largely unknowable. As Kant expressed it: ‘The attempt to establish the existence of a supreme being by

means of the famous ontological argument of Descartes is... so much labour and effort lost; we can no more

6

Dialogue Education

extend our stock of (theoretical) insight by mere ideas, than a merchant can better his position by adding a

few noughts to his cash account.’

ANSELM’S FIRST ARGUMENT SUMMARISED

------------------------------------Norman Malcolm considers that the first of Anselm’s arguments fails. He re-states the first argument as

follows:

1.

By definition, God is an absolutely perfect being possessing all perfections.

2. Existence is a perfection

3. Therefore God must possess existence [from {1) and (2)]

Malcolm accepts that Kant has effectively shown the second premise to be invalid and, therefore, considers

the first version of Anselm’s argument fails. He goes on (see below) to develop Anselm’s second argument.

ANSELM'S SECOND ARGUMENT - NORMAN MALCOLM’s VERSION2

------------------------------------------------------Anselm has two arguments. The one above occurs in Proslogion 2, but the more interesting one may be in

Proslogion 33. Malcolm begins by stating that if God does not already exist, God cannot come into existence

since this would require a cause and would make God a limited being which, by definition, God is not.

Similarly, if God already exists, God cannot cease to exist.

Therefore EITHER GOD'S EXISTENCE IS IMPOSSIBLE or NECESSARY. Malcolm then argues that God's

existence could only be impossible if it were logically absurd or contradictory and, as it is neither, then

God's existence MUST be necessary. The statement 'God necessarily exists', therefore, can be held to be

true. This argument can be stated in the following steps:

- Since God is a necessary being God must be either: (a) impossibly existent, (b) possibly existent, or

necessarily existent

- Since God is defined as a necessarily existent being, then God cannot be impossible [(a)] since no-one has

shown that there is a contradiction in the statement ‘God necessarily exists’

2

Charles Hartshorne put forward a version of the Ontological Argument which is almost identical to the one later put forward by Norman

Malcolm. However because Malcolm was writing in the field of analytic philosophy rather than theology, Malcolm’s version become more famous.

Hartshorne, as Malcolm, holds that God is necessarily existent and is either (a) Impossible and there is no example of it, (b) Possible and there

is no example of it, or (c) Possible and there is an example of it. (b) is nonsense as a possible necessary being is self-contradictory. (a) cannot be

shown to be true and Hartshorne argues there is nothing contradictory in the idea of God being a necessary being, so this leaves (c) which must,

therefore, be true - so God must exist.

3

‘And certainly this being so truly exists that it cannot be even thought not to exist. For something can be thought to exist that cannot be thought not to

exist, and this is greater than that which can be thought not to exist. Hence, if that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought can be thought not to exist,

then that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought is not the same as that-than-which-a-greater-cannot-be-thought, which is absurd. Something-thanwhich-a-greater-cannot-be-thought exists so truly then, that it cannot be even thought not to exist.

And you, Lord our God, are this being. You exist so truly, Lord my God, that you cannot be thought not to exist. And this is as it should be, for if

some intelligence could think of something better than You, the creature would be above its creator and would judge its creator - and this is

completely absurd. In fact, everything else there is, except You alone, can be thought of as not existing. You alone, then, of all things most truly

exist and therefore of all things possess existence to the highest degree; for anything else does not exist as truly, and so possesses existence

to a lesser degree. Why then did ‘the Fool say in his heart, there is no God’ when it is so evident to any rational mind that You of all things exist

to the highest degree? Why indeed, unless because he was stupid and a fool?’

7

Dialogue Education

- Since God is defined as a necessarily existent being, then God cannot possibly exist [(b)] - since a

necessary being cannot merely possibly exist. Further, a possible being is a dependent being which is

contrary to the definition of God.

- Therefore (c) must be true - God must necessarily exist.

Hick rejects this when he maintains that the most that can be said is that if God exists, God exists

necessarily. This is problem free BUT there is no way of getting rid of the 'if'. This is rather similar to

Descartes’ comments on a triangle or a valley - namely:

1. If there is a triangle, it must have three angles

2. If there is a mountain, it must have a valley,

3. Similarly if there is God, then God must necessarily exist.

Alvin Plantinga maintains that all Malcolm has shown is that the greatest possible being exists in some

possible world, but not necessarily in the real world (cf McGrath 'The refutation of the Ontological

argument' in Philosophical quarterly Vol. 40, 1990. No. 159. p. 210). Plantinga sets out the following steps in

Malcolm’s argument:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

If God does not exist, God’s existence is logically impossible,

If God does exist, God’s existence is logically necessary.

So it follows that either God’s existence is impossible or it is necessary.

The only way that God’s existence can be impossible is if it is contradictory.

The concept of God is not contradictory,

Therefore God necessarily exists.

Plantinga thinks that Malcolm’s key mistake is in premise (2) as Plantinga maintains that God could exist

without God’s existence being logically necessary. Plantinga maintains that it is POSSIBLE that God is a

logically necessary being but it is not NECESSARY that God is a logically necessary being. Therefore

Malcolm has not shown that the possibility that God is a logically necessary being is true.

Peter Vardy considers that Plantinga and Hick may well have misunderstood what Malcolm was trying to do –

and his understanding of Malcolm’s enterprise (which he thinks succeeds) is set out below.

ALVIN PLANTINGA’S REFORMULATION OF THE ARGUMENT 4

--------------------------------------------------Alvin Plantinga’s engagement with the Ontological argument has been deep and long lasting. He spent years

rejecting it and, in particular, he rejected Malcolm’s formulation (see above). Plantinga considers Anselm’s

argument to be not only fascinating but not to have been properly refuted, and he sets out to reformulate

it. He maintains that it is a ‘reductio ad absurdum’ argument:

‘In a reductio you prove a given proposition ‘p’ by showing that its denial, ‘not-p’, leads to (or more strictly

entails) a contradiction or some other kind of absurdity.... If we use the term "God" as an abbreviation for

Anselm’s phrase "the being than which nothing greater can be conceived" then the argument proceeds as

follows:

4

From ‘God, Freedom and Evil’ Alvin Plantinga. 1977

8

Dialogue Education

1.

God exists in the understanding but not in reality.

2. Existence in reality is greater than existence in the understanding alone (premise)

3. God’s existence in reality is conceivable. (Premise)

4. If God did exist in reality, then He would be greater than He is [from (2) and (3)]

5. It is conceivable that there is a being greater than God is [(3) and (4)]

6. It is conceivable that there be a being greater than the being than which nothing greater can be

conceived [(5) by the definition of ‘God’]

7. But surely (5) is absurd or self-contradictory; how could we conceive of a being greater than the

being than which none greater can be conceived? So we may conclude that:

8. It is false that God exists in the understanding but not in reality

9. It follows that if God exists in the understanding, He also exists in reality; but clearly enough he

DOES exist in the understanding as even the fool will testify; therefore He exists in reality as well.’

Plantinga considers that, effectively, step (3) means that it is possible that God exists - it is a possibility in

our understanding or to put it another way, there is a possible world in which God exists. This is a key move

in Plantinga’s argument. So he restates (3) as

(3*) It is possible that God exists

and, further, he re-states (6) as:

(6*) It is possible that there be a being greater than the being than which it is not possible that there be a

greater.

Plantinga claims that all the premises, if they are true at all, are necessarily true. He sets out to establish

the argument by reference to possible worlds. His steps are as follows:

There are, he claims, many possible worlds.

In some worlds you and I exist, in others one of us does and in still others neither of us do.

Plantinga’s claim is that God is a being of MAXIMAL GREATNESS who must exist in every possible

world and cannot not-exist.

As such, God is totally different from anything else who are merely possible beings and who may

exist in some worlds but not in others.

Plantinga’s claim is that to say that God has maximal greatness is to say that God has ‘an unsurpassable

degree of greatness - that is a degree of greatness such that it’s not possible that there exist a being

having more’.

9

Dialogue Education

How would one justify such a claim? Plantinga’s argument here is that if in any ONE world there was a being

of maximal greatness, then this being must necessarily exist in every possible world since if it had maximal

greatness there could not exist a world in which this being did not exist (to deny this, he claims, is to say

that the being is a merely possible being with a restricted amount of greatness). A being has maximal

excellence if it has maximal greatness in every possible world and it can only have maximal greatness in one

world if it has maximum excellence in any world.

This distinction between ‘maximal excellence’ and ‘maximal greatness’ is confusing and needs to be

unpacked. Plantinga says:

"A being’s excellence in a given world W... depends only upon the properties it has in W; its greatness in W

depends upon these properties but also upon what it is like in other worlds .......it is plausible to suppose that

the maximal degree of greatness entails maximum excellence in every world. A being, then, has the maximal

degree of greatness in a given world W only if it has maximal excellence in every possible world."

Effectively, then, Plantinga differentiates between maximal excellence (which entails omnipotence,

omniscience and moral perfection) and maximal greatness (which entails the property 'has maximal

excellence in every possible world').

Plantinga then re-states his argument as follows (there are various formulations, but this is a clear one: 5

1.

The property ‘has maximal greatness’ entails the property ‘has maximal excellence in every possible

world’.

2. Maximal excellence entails omniscience, omnipotence and moral perfection.

3. Maximal greatness is possibly exemplified as there is nothing contradictory in this claim hence we

can claim that there is a possible world in which it exists.

4. There is a world W* and an essence E* (by an essence, Plantinga means the nature of a thing…. In

the next premise he is going to refer to an entity X [by which he means God] which has the essence

E*) such that E* is exemplified in W* and E* entails ‘has maximal greatness in W*’ (Plantinga wants

by this to maintain that in this possible world E* has maximal greatness.)

5. For any object X, if X exemplifies E*, then X exemplifies the property ‘has maximal excellence in

every possible world’.

6. E* entails the property ‘has maximal excellence in every possible world’

7. If world W* had been actual, it would be impossible that E* fail to be exemplified. (this is true

because if something is true for any possible world, it would certainly be true if this possible world

were the actual world. Therefore if the possible world W* were real, then this entity X which has

the essence E* would have to have maximal greatness in every possible world. On this basis, once

5 Alvin Plantinga. ‘The Nature of necessity’ (Oxford, Clarendon, 1974). Pp. 214 – 215 also in Plantinga ‘God, Freedom and Evil’ Harper

Torchbooks, 1974 pps. 111 - 112

10

Dialogue Education

Plantinga has established ONE possible world in which a being has maximal greatness, because of the

definition of maximal greatness, it must be exemplified in every possible world.)

8. There exists a being that has maximal excellence in every possible word.

9. SO, this being must exist in this world!

Peter Vardy considers this to be largely word-play! What Plantinga has failed to do is to show that what is

possible must be real and whereas it is POSSIBLE that a being with maximal excellence exists, unless it can

be shown by evidence (which was Aquinas’, Kant’s and Hume’s challenge) that such a being is instantiated,

there is no reason to hold that it is. John Frye, Chief Examiner of the OCR examination board, puts this

more amusingly when he claims that Plantinga makes two invalid assumptions:

That whatever is possible must be instantiated (John Frye says: “It is possible that somewhere in the

universe is a one ton purple dragon called Horace, wearing a pink bow tie and natty long johns,

balancing upside down on his tongue with a water pistol in one hand and a trumpet in the other,

shooting passing gnats with the one and with the other playing ‘God save the Queen’, but somehow

I doubt it.”), and

That whatever is not incoherent must be true. Plantinga maintains his equations are not incoherent so

must be true. But a non-incoherent statement could be made about Frye’s Dragon which was

nevertheless false such as ‘Such a Dragon exists’ and if it does not then this would be a false statement.

Having said this, Plantinga is modest in what he claims his argument shows:

"What I claim for this argument, therefore, is that it establishes, not THE TRUTH of theism, but its

rational acceptability. And hence it accomplishes at least one of the aims of the tradition of Natural

Theology."

In reply to this Peter Vardy claims that Natural Theology does not simply seek to establish rational

credibility but a claim to reference - and this the argument fails to do. All the argument may do is to show

that the concept of God is not self-contradictory, and Plantinga does not need the ontological argument to

do this!

NORMAN MALCOLM REVISITED

--------------------------Peter Vardy considers that many people (including Plantinga and Hick) misunderstand what Malcolm is doing.

They all assume that he is trying to establish the de re necessary God of Aquinas, etc. - and this may not be

the case.

Perhaps God is not like this at all.

Perhaps it means something entirely different to say that God exists,

Perhaps God should not be considered to be an object in any way at all.

Some people say there is a God and others say there is not. This seems to involve a dispute about a kind of

object, a 'something'. However this may well be an error. Let us remind ourselves what Anselm says:

11

Dialogue Education

"...the fool hath said in his heart 'There is no God', but at any rate this very fool, when he hears

of this Being of which I speak - a being than which no greater can be conceived - understands what

he hears, and what he understands is in his understanding; although he does not understand it to

exist."

Believers do not go round saying 'God exists' - rather they take part in worship, they pray, go to Church,

sing hymns and read their Bibles. All these activities PRESUME the existence of God. They do not first set

out to prove the existence of God and only then go to Church. They are either brought up in a group of

people who go to Church or they come to see the value of belonging to a religious community.

D. Z. Phillips and Fr. Gareth Moore OP are anti-realists (this is Peter Vardy’s claim - but beware that they

do not call themselves this, so Peter Vardy may be mistaken!) and they, amongst many others, consider that

God's existence or reality cannot be considered to be talk about the existence of an object, God is not a

something. God is not a substance6, rather talk of God is presupposed in the religious way of life. Norman

Malcolm sees Anselm's argument as having the force of a grammatical observation. When believers talk of

God they are talking of God's inescapable reality to them. It is worth remembering the context in which

Anselm put forward his proof. He says in the Preface to his Proslogion:

"I have written the following treatise in the person of one who... seeks to understand what he

believes..."

For Anselm, God's reality is inescapable and he is trying to express this in his argument. He is trying to

understand more fully what he already believes - this is very different from trying to prove God's

existence to someone who does not accept it. Phillips maintains that the believer is the person for whom

God's reality is inescapable. For him or her God could not fail to exist. 'OF COURSE', he or she might say,

'GOD EXISTS. God's existence is that on which my whole life is based'.

A parallel might be with the equator (Gareth Moore's example). OF COURSE the equator exists - it is real

and exists ONCE ONE HAS UNDERSTOOD WHAT THE EQUATOR IS. This does not mean, however, that

there is a physical line which the equator represents. Instead the equator is an idea which we all accept.

We live in a form of life in which the equator is real. The same may be said of God - to the believer God is

real and exists - God's reality is undoubted. All praise, all exultation, all of the believer's life is related to

the reality of God which it does not make sense to doubt. God is the reality to which all of the believer's

life is directed. This does not, however, mean that God is an object - rather God is a reality within the

believer's form of life.

6

Gareth Moore very firmly says that God is nothing, there is nothing that is God. No event in the world can be

described as ‘God did it’ and to fear God is to fear nothing, it is to live without fear (cf ‘Believing in God - a Philosophic

Essay’ T & T Clarke)

12

Dialogue Education

Within the community of believers, God is real and God exists - but those outside this community do

not have any use for language about God. On this basis, the 'fool who has said in his heart there is

no God', may be the person who has no use for praise, for worship or for ritual. To him or her,

God-talk has no reality.

Malcolm offers an example of a statement about existence which can be logically necessary as ‘There

are an infinite number of prime numbers’ - however this exactly shows what his formulation may achieve.

Within the language game of mathematics, it is true that there are an infinite number of prime

numbers. Similarly within the language game of religious belief ‘God necessarily exists’ may be true. But

neither statement may have any truth outside the communities that use this language.

ON THIS BASIS, the ontological argument may be valuable in pointing us to the sort of reality God has.

God is not, on this view, an object - God is not a thing. God is rather an idea within the form of life of

the believing community. To the believer, God necessarily exists - like prime numbers exist for the

mathematician. It simply does not make sense to deny the reality of God - but this does not mean that

God or prime numbers are to be thought of like objects.

Understanding this is not entirely easy and it is worth referring to the discussion of anti-realism in

Peter Vardy’s ‘The Puzzle of God’ to make the issues clearer.

J. N. FINDLAY7

-------------J. N. Findlay uses the Ontological argument to DISPROVE God's existence. The weakness of his

argument is that he maintains that God must DE DICTO NECESSARILY exist and God CANNOT exist

like that if God is in some sense a 'something'. If you accept his premises, his argument is valid.

However if one rejects his premises and holds that God is de re necessarily existent, then his argument

fails.

His argument can be unpacked as follows:

1.

God must be a necessarily existent being as anything less than a necessarily existent being is

not worthy of worship,

2. Necessary statements about existence cannot be true (as Hume and Kant maintained) as

necessity only applies to the way words are used - in other words to de dicto necessary

statements like ‘spinsters are female’

3. Therefore God cannot exist

Geisler and Corduan re-state this to say:

1.

The only way God could exist is if he exists necessarily (if God was in any sense contingent then

he would not be God)

2. But nothing can exist necessarily (for necessity only applies to propositions not to anything that

exists in reality)

7 Summarised in Geisler and Corduan’s ‘Philosophy of Religion’ Baker Book House. P. 136

Page 13 of 14

Dialogue Education

3. Therefore God cannot exist

The key point is (2). It is highly debatable whether Kant’s rejection of necessary existence is correct –

at least as simply stated as Kant maintains. St. Thomas Aquinas maintained that God exists de re

necessarily - in other words God is a necessarily existent being. God is neither something, nor nothing God is in a category of God’s own which transcends the categories of something or nothing. It is true

that there is no proof that such a being exists (this is the problem with the Cosmological argument) but

it is NOT the same as saying ‘God exists’ is de dicto necessarily true. So there is no contradiction in the

claim that ‘God exists de re necessarily’ and unless this can be shown to be a contradiction, Findlay’s

disproof fails.

SUMMARY

--------Does the Ontological argument succeed? It all depends. If God is in some sense an object apart from

the universe which He created then the ontological argument cannot prove His existence. Perhaps this

God exists, perhaps He does not - but if we would try to prove it we must, as Aquinas says, do it

starting from the world around us. We cannot define God into existence nor can we move from some

definition of God to prove His existence.

If, on the other hand, God is real and exists within the form of life of the believing community, then

God may indeed exist and be real - God may necessarily exist WITHIN THE FORM OF LIFE OF THE

BELIEVING COMMUNITY. The fool is missing something as he is yet to understand what talk about

God is about, he has yet to find God's reality. Finding this reality is not a matter, however, of

discovering a lost object of some kind - it is a matter of finding meaning and purpose in praise, in

religious ritual and religious language. The believer maintains that 'God necessarily exists' is true

rather like 'the equator exists' is true - the unbeliever has no use for this language. The KEY areas for

you to be aware of are:

1.

That the ontological argument is a priori

2.

That it wants to hold that 'God exists' is analytically true

3.

That it wants to maintain that 'God exists' is therefore de dicto necessary

4.

That everything depends on the definition of God.

5.

IF God is considered to be in any sense an object or substance apart from the Universe, then

Aquinas, Hume and Kant's criticisms succeed - you cannot arrive at God's existence by analyzing an

idea,

6.

IF, however, God is a reality in the form of life of the believing community, then the argument

may be pointing to the inescapable reality of God within the believers form of life.

The argument is probably the most fascinating of all the arguments for the existence of God as it is

not just a matter of success or failure but it forces us to consider what 'God exists' means and what

would make it true.

Dr. Peter Vardy

Vice Principal

Heythrop College,

University of London

Page 14 of 14