Transferability_ICERI_Paper

advertisement

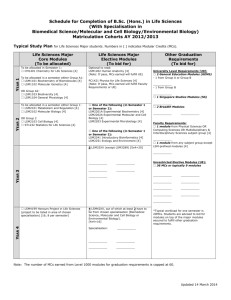

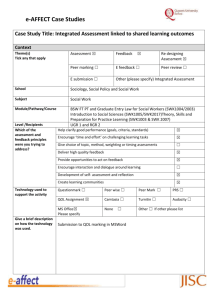

Ensuring each student reaches their potential: transferability issues Lorna Sibbett Abstract Isolation of knowledge within disciplines, or for students, within the confines of single taught modules, diminishes the learner’s richness of understanding. Whilst flexible degree programmes are attractive to prospective students, there is a need to ensure that such programmes do not situate understanding within narrow contexts. The curriculum must provide both incentive and structure for students to develop transferability in their knowledge and skills. Transferability of skills is dependent upon transfer of both principles and dispositions [1]. Teaching to maximise the former requires active development of student understanding of generalisable principles, this being a minimum aim of any educator. However, transfer of dispositions, for example towards critical thinking, is more problematic, particularly within the higher education (HE) sector where individual students are exposed to varied tutors and lecturers, each of whom has built a career upon arguing the uniqueness of their thoughts and approaches. In the University of St Andrews School of Biology, introduction of core skills teaching has facilitated and integrated learning across modules and from co-curricular activities. This structure has been successful in establishing transfer of both principles and dispositions. This reflexive analysis reviews the strategies and successes of this programme in relation to transfer conditions. Keywords: Transferability, skills, dispositions. What is transfer and why is it important? Transfer may be investigated by comparing student performance in specific tasks, before and after teaching for transfer: “Transfer is a phenomenon involving change in the performance of a task as a result of the prior performance of a different task. It is immediately apparent that this definition scarcely distinguishes ‘transfer’ from ‘learning’”. [2, 3] Transfer is observed if success in a new context is observed; the knowledge or skills must be garnered from a one context and applied in a new one: “Transfer, the process of using knowledge or skills acquired in one context in a new or varied context”. [4] A teacher’s goal is for their student to truly understand, to take knowledge and construct meaning from it. Learning without the ability to transfer to fresh contexts is an illusion of learning, although recall-based assessment tasks will not recognise this as a mere façade. There is a danger that ability which is orphaned of disposition to transfer, will fail upon removal of a teacher’s prompts to explore wider understanding. Teaching for transferability of skills such as critical thinking, requires development of competence and positive disposition to transfer. Thus successful teaching promotes the transfer of both principles and dispositions; and operates in the affective domain. “Skills for Biologists” (“Skills”), a Second Year course at the University of St Andrews, aims to equip students with tools to succeed in higher education (HE) and with certain tools and habits for a rewarding life. The obvious course focus is on skills such as critical evaluation, statistical analysis and writing lab reports. However, individuals are also verbally encouraged to evaluate their opinions, beliefs, priorities, time management and interpersonal interactions. Structure of “Skills for Biologists” The School of Biology, University of St Andrews, offers three Second Year courses (BL2000 level) per semester. Each course is worth 30 credits, with students required to gain 120 credits across the academic year. Each year approximately 90 to 100 students take two Biology modules per semester; 80 to 90 study one Biology modules plus subject(s) from another discipline. Skills for Biologists is not a separate credit-bearing module, rather it contributes 20% of the continuous assessment for each BL2000 level module. The course runs across the whole academic year. Semester 1 contains a taught programme of weekly lectures and fortnightly threehour workshops based in a computer classroom. Semester 2 provides six lectures and two workshops, with the remaining time allocation of three hours per fortnight being spent on small group projects. The course has online support via a virtual learning environment (WebCT course), which provides materials of general utility across all four years of undergraduate education. Any student studying a biology module has access to these materials. Integration of skills learning and promotion of transfer across modules “Skills for Biologists” provides introductory theory, opportunities for practice and explicit references to events in sister modules. The Skills for Biologists teacher (and author of this paper) makes explicit references to how and when certain skills may be utilised in the sister modules. Concurrently or soon afterwards, within their BL2000 modules, students apply their understanding of, and competency in, specific skills. The “Skills for Biologists” organiser teaches extensively within pre-honours courses; organises several other Biology course; is a pre-honours Adviser of Studies; and academic link with the University Careers Centre. She is key point of contact for students seeking advice on aspects of their coursework and career plans. Integration of this course with the wider formal and informal curriculum is principally achieved through the use of this single staff member as the key skills facilitator, advisor, supporter and promoter. She possesses detailed knowledge, shared with students, of the other BL2000 modules: activities; deadlines; assessment criteria; ethos; flexibility and management. Module organisers of the other modules are relieved of primary teaching for the development of many skills; instead they build upon introductions from the “Skills” course, proving fresh contexts and opportunities for student to improve in competence. The School of Biology has several Teaching Fellows, numbered amongst which is the “Skills” organiser. These Teaching Fellows maintain substantially higher student contact hours than other academic staff and form a vital spine for teaching and integration of teaching within the school. For students they are highly visible, frequently encountered and trusted. We believe that such judicious personnel appointments and deployment contributes greatly to curriculum integration; innovative teaching; and excellent student experience. Other academic personnel are vitally involved in teaching and module organisation, but sufficient of their time remains available for investment in research. “Skills for Biologists” ethos Underpinning this course is the belief that learning is promoted when the learner is engaged in dialogue, explaining their understanding and simultaneously revising it, then responding to the challenge of teacher / peers by reconstructing a better understanding. We strive not for the situated learning described by e.g. Brown et al, 1989 wherein known is socially constructed and isolated within that social context. The use of multiple contexts and the exploration of understanding is an adventure undertaken within a community of learning. “Transfer is promoted when learning takes place in a social context, which fosters generation of principles and explanations. Transfer improves when learning is through co-operative methods.” (Billing, 2007) Course review in relation to transfer conditions Table 1 summarises key conditions for transfer as suggested by Alexander and Murphy (1999) and Bransford et al (1991). Matched with these conditions are suggested strategies by which “Skills” has empowered learners for transfer. Learning contexts are rich and multiple, but there is a common strand “…the seeds of transfer are more likely to take root when those in the classroom community see themselves as progressing toward competence in specific fields of study”. Alexander & Murphy (1999) In Semester 1, adoption of a biological topic strand, namely obesity and its possible association with cardiovascular disease (CVD), enables students to inhabit a domain of scientific research and sense progress in using a range of new tools to build understanding within the topic. Importantly, this topic is routinely subject to media attention; new research in the field is frequently published; many people have emotional connections to either weight issues or CVD; and CVD is taught within another BL2000 level module. Each of these factors contributes to students’ learning and transfer motivations. In Semester 2, students work in small groups of four to five to devise, perform and report upon an investigation of their choosing. Such investigations are primarily in the fields of ecology, physiology (particularly sports science) and psychology, with students bringing subject expertise from other modules or co-curricular activities. “Students should be shown how the knowledge and skills they attain in one problembased situation have utility in other relevant contexts” Alexander & Murphy (1999) In both semesters, lectures, workshops and self-study exercises make use of multiple examples and contexts from out-with the common strand. Table 1 Teaching practice in “Skills for Biologists” matched to transfer conditions suggested by Alexander and Murphy [4] and Bransford et al [6] Transfer condition Skills for Biologists Transfer is an essential aspect of competent performance in any complex domain. [4] Transfer is regarded as an educational fundamental; education for transfer of skills is the raison d’etre of this course. Skills and knowledge must be extended beyond the narrow contexts in which they are initially learned. [6] Skills learned within this course are employed in other modules. Transfer is more likely when the learning environment is designed to encourage cross-situation and crossdomain transfer and to reward this and when the learner has undergone enculturation into the domain. [4] Adoption, for each semester, of a common strand, which is personally interesting and has social currency. People are helped, in trying to learn independently, if they have conceptual knowledge, mental representations of problems (including how one problem is similar and different from others), and understanding of the relationships of the components in the overall structure of a problem. [6] Transfer and analogical reasoning are related processes. [4] The conditions of the transfer involve aspects of the learner, the content and the context. [4] Multiple examples and contexts are compared with / within the common strand of inquiry. Learning contexts are rich and multiple across situations and domains. The teacher routinely employs analogy. Student use analogies to aid communication within collaborative learning groups. Learning is built upon prior experiences and knowledge. The learner must understand the conditions of application – when what has been learned can be used. [6] Learning objectives are made explicit for each workshop and lecture. Such objectives are explicitly linked to activities within other past, current and forthcoming modules. Learners are most successful if they are self-aware as learners, and have appraisal strategies which keep learning on target and which keep asking themselves if they understand (ie metacognition). [6] Discussions on individual achievements are frequent. Students are encouraged to recognise and share one another’s strengths. Teaching and rewarding analogical thinking Poets, novelists and teachers think in analogy. Creation of personally meaningful analogies creates personal meaning. Effective teachers create analogies, which resonate with learners to engage each in construction of personal meaning. In “Skills” statistical formulae are not explained using statistical theory, but via analogy. For example, the formula for Pearson’s product moment correlation is dissected via thoughtful remembrances of playing see-saw during childhood. The impact of a datum with large deviation from the mean is analogous to a heavy child at a distance from the pivot of the see-saw; a multiplied pair (product) of data generates a large moment (motion around the pivot). Analogies with the familiar, particularly those triggering multiple sensations, provide a familiar framework upon which the unfamiliar can be sketched. Throughout students work in collaborative learning groups in which they explain actions and understanding to one another. Analogies and descriptions of alternative contexts, including those from out-with Biology, are encouraged. The power of small conversations is used to direct learner focus, gauge individual understanding and reward learners. An encouraging word, smile and eye contact within a small group suggest social value and a sense of belonging. Such conversations may be as productive without teacher presence, but the teacher is careful to engage with each group, sitting down with them rather than standing over them to imply respect and willingness to share. Learning is built upon prior experiences and knowledge In primary and secondary education learning takes place in classrooms and laboratories; both terms which suggest collaboration and activity. In HE, students sit in lecture theatres; theatres in which lecturers perform for a potentially passive audience. As effective learning builds on prior experience, if the lecturer is to educate rather than entertain, they require awareness of students’ earlier courses, wider interests and culture. Within this course, teaching, including lecturing, is centred upon such awareness of the learner. Teaching is under pinned by respect for the student’s prior understanding and awareness, made explicit, of the emotional contexts, which impair or support learning. The course requires students to develop competency in statistical analyses, including selection of appropriate statistical tools. Common ground is found in viewing statistics as one of many tools, which can be used to answer biological questions. Prior confidence in such material is varied from virtual phobia to the security of someone who is a statistical specialist. Negative self-beliefs would impede acquisition of new knowledge and understanding. It is made explicit that each student is expected to: employ key statistical and other tools at a self-appropriate level of competency; take responsibility for decisions regarding which skills are their current priority; and make progress. It is also made explicit that prior poor performance in, or dislike of, mathematics is no excuse for abstinence from its many productive uses. Learning objectives are made explicit Specific learning objectives are provided for each taught component. Such objectives are not lists of knowledge items, but statements of what students are expected to be able to do. Orally these objectives are re-engineered to reflect students’ co-curricular activities, thus establishing an expectation of transfer between the formal and informal curriculum. Discussions on individual achievements are frequent Praise, for specific student achievement, is offered frequently. Students are apt to declare frustrations at perceived self-incompetence, but are redirected to focus on what they have achieved; how and where such achievement can be applied. Such suggestions of later application may be general or specific references to forthcoming activities in their biology modules. Students are encouraged to recognise and share strengths Throughout Semester 1, students are encouraged to work in triplets. There is a shared expectation of work in collaboration with peers, but with teaching support. In Semester 2 project teams, employing a key staff member as a consultant, work towards a poster report of their investigation at an in-house student conference. During the conference, intra-team meetings are used to acknowledge and thank individuals for the specific roles they played and skills they brought to the project. These meetings are honest, but positive, and generate self-reflection. Intra-team assessment is used to agree a distribution of project marks amongst the team members. Inter-team assessment, wherein students mark and provide feedback for the posters of others, is used to give immediate feedback on performance and to increase individual awareness of criteria for success. Measures of success Student feedback, via end-of-module questionnaire, Student-Staff Consultative Council and informal conversations is superlative in praise, with students reporting increased confidence and competence in, for example: data analysis; communication via laboratory reports and posters; critical evaluation; experimental design and effective team-work. They asked that other years of study be supported in similar manners. We are now doing so for Junior Honours. Lecturers encounter students with skills deficiencies, but acknowledge that the “Skills” course efficiently promotes skills acquisition and minimizes deficiencies. Students deliver on the expectation that skills will be transferred. Many students, from all years of study, consult the “Skills” teacher regarding specific activities in other modules. Such action is evidence of disposition to transfer. Know the student Bereiter (1995) maintained that transfer of principles is promoted by teaching for increased depth of understanding. In “Skills”, we teach for understanding greater than simple accrual of information. Bereiter (1995) suggested that transfer of dispositions requires incorporation into character. Change in character requires emotional and social involvement of, and with, the learner. Teacher and learner cannot be strangers to one another. Indeed teacher, learner and peers are learners together. Learning is increased via teaching strategies, which build, reward and value strategic ability to transfer, whilst stimulating and rewarding interest. Such rewards can be provided as weighting of assessment value towards evidence of such skills and dispositions, or personally addressed feedback from a teacher or peer. Positive social standing is a reward, which is employed in effective teaching for transfer. Education enriches the individual with appreciation of complex realms imagined or understood by our consciousness; education empowers the individual to perform a valued role in society. Learning is personally constructed upon foundations of earlier learning and upon frameworks provided by skilled teachers. This is often a busy and noisy construction site, wherein is found humour, good stories and debate. Emotion is here and learners are motivated to become intellectual artisans. Education for transfer of skills must improve disposition to transfer as well as the understanding essential for transfer of principles. The requisite teaching strategies for success are learner centred and may demand a re-think of (a) curriculum design in which transfer of learning across modules is facilitated and rewarded, and (b) staff deployment, such that certain teachers become recognisable as experts on each student cohort, indeed expert on each student. This is a challenge in the era of mass HE, but a challenge we must meet if HE is to provide graduates, who are disposed to higher order thinking and application of their skills. References [1] Bereiter, C. A Dispositional View of Transfer p21-34 Teaching for Transfer: Fostering Generalization in Learning, editors McKeough, A. et al. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0805813098. 1995. Alexander, P.A.; Murphy, P.K. Nurturing the Seeds of Transfer: A Domain-Specific Perspective. International Journal of Educational Research, v31 n7 p561-76, 1999. Billing, D. Teaching for Transfer of Core/Key Skills in Higher Education: Cognitive Skills. Higher Education:The International Journal of Higher Education and Educational Planning, v53 n4 p483516, 2007. Bransford, J.D.; Brown A.L. and Cocking R.R. (Ed.) How People Learn. National Academy Press, Washington , D.C. ISBN 0-309-07036-8. 1999. Brown, J.S., Collins, A. and Duguid, P. “Situated cognition and the culture of learning”, Educational Researcher 18(1), 32-42. 1989. Gick, M.L. and Holyoak, K.J. “The cognitive basis of knowledge transfer” in Cormier, S.M. and Hagman, J.D. (Eds), Transfer of Learning: Contemporary Research and Applications. San Diego: Academic Press Inc, pp9-46. 1987.