DRSEA_INFORMER_Volum..

advertisement

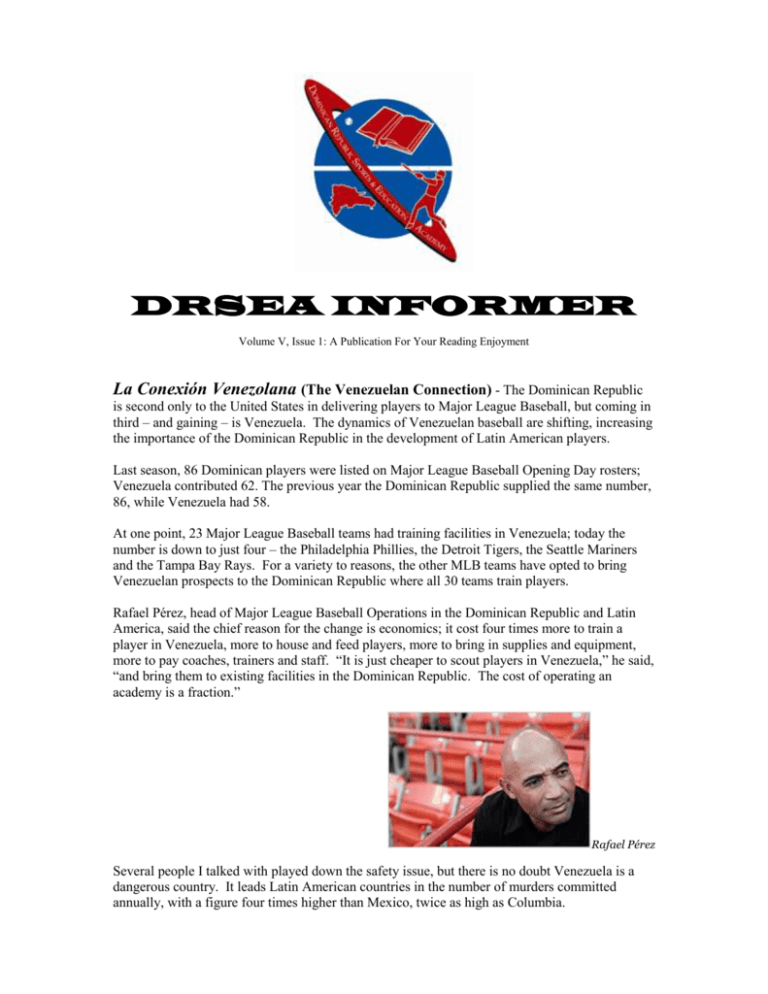

DRSEA INFORMER Volume V, Issue 1: A Publication For Your Reading Enjoyment La Conexión Venezolana (The Venezuelan Connection) - The Dominican Republic is second only to the United States in delivering players to Major League Baseball, but coming in third – and gaining – is Venezuela. The dynamics of Venezuelan baseball are shifting, increasing the importance of the Dominican Republic in the development of Latin American players. Last season, 86 Dominican players were listed on Major League Baseball Opening Day rosters; Venezuela contributed 62. The previous year the Dominican Republic supplied the same number, 86, while Venezuela had 58. At one point, 23 Major League Baseball teams had training facilities in Venezuela; today the number is down to just four – the Philadelphia Phillies, the Detroit Tigers, the Seattle Mariners and the Tampa Bay Rays. For a variety to reasons, the other MLB teams have opted to bring Venezuelan prospects to the Dominican Republic where all 30 teams train players. Rafael Pérez, head of Major League Baseball Operations in the Dominican Republic and Latin America, said the chief reason for the change is economics; it cost four times more to train a player in Venezuela, more to house and feed players, more to bring in supplies and equipment, more to pay coaches, trainers and staff. “It is just cheaper to scout players in Venezuela,” he said, “and bring them to existing facilities in the Dominican Republic. The cost of operating an academy is a fraction.” Rafael Pérez Several people I talked with played down the safety issue, but there is no doubt Venezuela is a dangerous country. It leads Latin American countries in the number of murders committed annually, with a figure four times higher than Mexico, twice as high as Columbia. The fact that a Major League Baseball player from Venezuela, Wilson Ramos, a catcher with the Washington Nationals, was kidnapped a few months ago and held for ransom, certainly didn’t add to the appeal of the country. Ramos was rescued unharmed by the Venezuelan army. Add to that what Rene Gayo, the Pittsburgh Pirates director of Latin American scouting, described as an anti-American attitude and the Venezuelan exodus is further explained. “With the anti-American sentiments and [Venezuelan President] Hugo Chávez, and radical dialogue, people are moving out,” he said. The Pirates closed down their Venezuelan academy last year because of the political climate and the danger factors, according to Gayo. “Hoodlums would come on payday,” he said, “and rob everybody at the academy. Over the years, little by little, ever since Mr. Chávez took power, indications are that things are going in an opposite direction. Either Chávez gets out of power, or he will make it into the Cuba of the 21st Century.” Rene Gayo He added, “Our owner made a significant investment in the Dominican Republic. We wanted to streamline, so it was economically intelligent to do what we are doing. By certain measures, all that really matters is how well the players play.” Major League Baseball recently hosted a talent showcase featuring the top 25 unsigned prospects from both Venezuela and the Dominican Republic; those players can be signed July 2. Gayo said that forcing players from the two countries to compete head-to-head hasn’t created additional concerns or problems. “There has always been a sense of nationalism of competition in Latin America,” he said, “particularly at the entry level. But they come to the U.S. united by common obstacles of language and culture, so they are equal there.” The four teams with operations in Venezuela did not respond to requests for comment. El Mismo Juego De Nombres (Same Name Game) – Dominican authorities have arrested yet another Dominican baseball player on charges of faking his identify, this time for more than 11 years. Fausto Carmona, a pitcher with the Cleveland Indians, was outside the U.S. consulate in Santo Domingo when he was busted for falsifying both his name and birth date when he was signed as a free agent in 2000. Carmona’s real name is Roberto Hernández Heredia and he is 31 years old, three years older than he reportedly led the Indians to believe. The Indians placed Carmona/Heredia, who was released on bail, on baseball’s restricted list pending the outcome of his case; he will not be paid until free of his legal predicament. He was schedule to earn $7 million in the upcoming season. Fausto Carmona Carmona’s arrest comes only a few months after Florida Marlins pitcher Leo Núñez - who is actually Juan Carlos Oviedo – revealed he played under an assumed name and age for 10 years. He was arrested briefly but released after authorities in the Dominican Republic said he would not be charged in the investigation of his use of fake documents. He was also placed on the restricted list. I have been told that more than two dozen current major league and minor league players from the Dominican Republic are in the same fix as Carmona/Heredia and Núñez /Oviedo, and, like them, failed to come forward when MLB offered amnesty in 2008 to players who admitted falsifying their names or ages. Major League Baseball has been plagued for years with age and identity fraud problems in the Dominican Republic and initiated a major reform movement nearly two years ago. While the problem has been curtailed, it has not been eliminated as the Núñez and Carmona cases demonstrate. Major League Baseball rules provide a year suspension for minor leaguers who commit identity fraud; major leaguers are penalized at the discretion of the commissioner’s office. But the legal issue of a forged identity can bar a player from receiving a U.S. visa, effectively ending his career. Lecciones De Mi Padre (Lessons From My Father ) – As each Valentine’s Day approaches, I am of mixed emotions. My girlfriend drops hints almost daily on what would be the appropriate gift. I am thinking flowers and candy; she is thinking a Blackberry and shoes. But the day is not without sadness for me. My father would have turned 98 on February 14, so the day is an annual – sometimes painful – reminder that I am no longer blessed to have him in my daily life, only in my daily memories. I often think about what would be his take on my efforts, my goals in the Dominican Republic to build a sports and education operation that would help bridge the academic gap that the majority of baseball players in the country face. I am convinced that as we edge closer and closer to the day when dream is reality, he would be proud. My father grew up in poverty. His father abandoned the family; my grandmother worked as a domestic to feed and cloth her three children. Education transformed my father’s life. He went to college in 1930 at age 16; I often try to imagine what it must have been like to be Black and intelligent in those days of segregation, of the overt racism he faced every day. He attended Lincoln University, the oldest historically Black college in the U.S., and excelled academically. People would later describe him as so poor during his college years that he wore an overcoat patched and mended so many times he needed a combination to get in and out of it. My dad during his student years After a stint in the Army during World War II, he returned to school, attending Ohio State University where he became the first African American to earn a PhD in English. He successfully served as a graduate assistant despite concerns that white students might resent taking instructions from a Negro. Graduation day at Ohio State Unable to get a job at a white institution because of the color of his skin, he returned to his alma mater, teaching English and journalism for 38 years, then remained as a mentor, tutor and friend to thousands of students. Those he influenced went on to become doctors, lawyers, teachers, judges, and even a couple of Pulitzer Prize winners. All my life he was my mentor and tutor and – in the last years of his life – my friend. I remember when I was 10 or 11, he was offered a job at a prestigious white institution, a rare occurrence in those days. It came with an annual salary of $14,000, a princely sum in those days, but Dr. Farrell turned it down, much to my dismay at the time as he explained, “Charles, life is not always about money.” That is one of the many valuable lessons he taught me over the years as our relationship developed from father-son, to mentor-mentee, to friends as I came to understand that what he expected of me was no more than I eventually came to understand was what I was capable of accomplishing. He was never one to hand out a lot of accolades, so when he expressed pride in me as my journalism career developed, I knew it was earned respect, and a lot of it based on the command of English I mastered under him. Now, I think about him every day; how wise and wonderful he was, how determined he was to make a difference in the world, to influence and inspire people to live up to their potential, to excel in life. I believe he would be proud of the path I am on today as I advocate educating those less fortunate than myself who live in a Third World country, a developing nation where baseball provides both entertainment and career aspirations for the multitude. I think how education altered his life, directed mine and gave purpose to both our lives. As we move closer each day to turning the Dominican Republic Sports & Education Academy into reality, I remain mindful of the lessons my father taught me and their influence on my decisions. I know that the lives of those the DRSEA aspires to educate can and will be drastically altered in meaningful ways, ways that dollars and pesos cannot measure. Happy Valentine’s Day, Dad. Poniendo La Pobresa En Perspectiva (Putting Poverty Into Perspective) – You get a different view on the race for the presidency of the United States when the view is from the Dominican Republic, which has its own set of problems, economic and otherwise. And as such, the antics of the Republican candidates take on a far different perspective living in Santo Domingo than living in New York City. I have followed the debates with interest generated mainly over who will be Barack Obama’s opponent next fall, and I have to say I cringe at the prospects. But Mitt Romney’s outlandish comment that he didn’t worry about the poorest Americans, wasn’t concerned since they had safety nets, was unsettling, to say the least, coming from a man worth $200 million. In living in the Dominican Republic, I have told myself that I will never get comfortable with the level of poverty I witness here on a daily basis. It is different, it is more profound, more pervasive than in the United States – and there are no safety nets such as welfare, food stamps, Medicare or Social Security. All too frequently, people don’t exist; they survive. There is definitely a wealth gap in the Dominican Republic. I see mansions and yachts and luxury cars, but I also see tin shacks with no plumbing, blackouts the norm, and limited food sources in far too many homes, impossible to stretch to provide solid nutrition. Health care is generally good in the country, but seeing a doctor can still boil down to a choice between addressing a baby’s cough or putting some food on the table. It is not the poverty with safeguards that Mitt Romney tosses aside while counting his millions. Yet the Dominican Republic is rich in people, in culture, in fortitude. Dominicans are said to be the second happiest people in the world, after Costa Rica. People here with little share what they have, living for today while hoping for tomorrow. “God will provide,” they tell me, and somehow He does. It is not unlike the promise of baseball, the dream sold to millions of Dominican boys who hone their skills under the hot Caribbean sun for a slim shot at Major League glory and the riches that go along with it – riches that transform life in the Dominican Republic, riches that eliminate the daily struggle to survive. But the reality is that stardom in baseball – moving from rags to riches – is reached by only a few. By Major League Baseball’s own account, only two in 100 top prospects will even make the minor leagues in America, let alone the Big League. And most of those 98 rejected return to the poverty they so desperately sought to escape. The fact that the vast majorities are uneducated or undereducated only compounds the situation, and their poverty becomes an endless cycle. I see the hopes and dreams reflected in the eyes of so many boys who pursue baseball; I see the fire extinguished in the eyes of those who have failed. Education, in and of itself, is a safety net, opening up vast areas of opportunity where none existed. Where Baseball Is Born photo Unfortunately, education for Dominican prospects is as elusive as the baseball dream they chase. With no safety net to break their fall, reality lands hard. Charles S. Farrell DRSEA Contact Information in the Dominican Republic Address: Calle 19 de Marzo, #103, Suite 305, Zona Colonial, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic Phone: 829-505-2991 Website: www.drsea.org Myspace: Myspace.com/drseaorg Twitter: Twitter.com/drseaorg Facebook: www.facebook.com/drseaorg Please feel free to pass the DRSEA INFORMER on to others you feel might be interested in being updated on what we are doing or send their e-mail to include them on the mailing list. The INFORMER is published on a regular basis; back issues are available on our website. Reprint by permission only.