THE ETHOS OF THE ROYAL MARINES

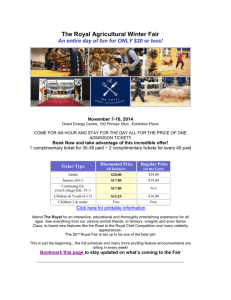

advertisement