Idiopathic Interstitial Lung Disease

advertisement

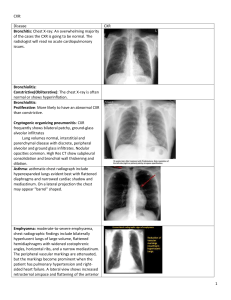

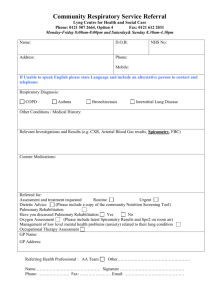

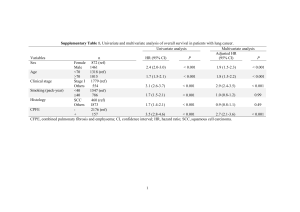

Idiopathic Interstitial Lung Disease The term idiopathic interstitial pneumonia refers to a group of disorders rather than to a single specific diagnosis. This group includes in decreasing order of incidence: usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis (NSIP) bronchiolitis obliterans-organizing pneumonia (BOOP) respiratory bronchiolitis associated interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD) desquamative interstitial pneumonitis (desquamative IP) lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (LIP) acute interstitial pneumonitis Because acute interstitial pneumonitis presents in a uniquely acute manner, it is not discussed here. The chronic conditions are discussed together because they have common clinical, radiographic, and physiologic presentations in the absence of a defined cause. These idiopathic disorders are a distinct subset of interstitial lung diseases, and in each patient, known causes of interstitial lung disease must be ruled out. The idiopathic disorders are processes that are characterized by variable amounts of fibrosis and/or inflammation that affect the interstitium to a greater extent than they do the airways or alveoli. UIP, the most common of these disorders, is the pathologic diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Our knowledge of each specific disorder is rapidly growing, and we must keep in mind that among the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, each disease has its unique treatment and prognosis. PREVALENCE The incidence of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia is not known. Because of the recent changes in pathologic classification, and thus disease diagnosis, older estimates are not valid. In 1994, a population-based registry in Bernalillo County, NM, reported that the prevalence of all interstitial lung diseases was 80.9/100,000 among males and 67.2/100,000 among females. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was the most common diagnosis, and males had a higher prevalence (20.2/100,000) than females (13.2/100,000). This study also found that the yearly incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis was 10.7/100,000 among males and 7.4/100,000 among females. Patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are generally elderly or middle-aged; approximately two-thirds of patients are older than 60 years at diagnosis. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis has no specific geographical distribution; it is found in equal proportions in urban and rural environments. A history of smoking has been associated with an increased risk of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, but general dust exposure has not. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY The classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias has evolved over the past few decades. Although the current classification system may seem to be somewhat arbitrary, it conveniently groups patients with similar pathology , disease progression, treatment response, and prognosis. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the clinical diagnosis correlated with the pathology of idiopathic UIP, is the most common diagnosis, and its possible etiology is the most studied. The lack of benefit seen with corticosteroid and cytotoxic medications has spurred researchers to discard their once-held belief that fibrosis and disease progression is caused by inflammation. Current theory suggests that idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is caused by a recurrent lung injury or an autostimulating process. These conditions are thought to be akin to aberrant wound healing and progressive scarring in other organs. The repeated stimuli are believed to precipitate an increase in cytokine production, which leads to cytokine dysregulation in susceptible patients, and a proliferation of fibroblasts, which increases extracellular matrix deposition and leads to physiologic impairment. Recent research suggests that the cytokine dysregulation involves abnormal elevations of type 2 cytokines and reduction of type 1 cytokines, possibly in the presence of elevated transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta. The evidence for this hypothesis is derived from numerous animal and human studies. Mice with bleomycin-induced fibrosis manifest elevated levels of type 2 cytokines; the fibrosis is reduced by antibodies to these cytokines as well as by induction of interferon (IFN)-gamma, which is a type 1 cytokine.8-11 Human studies have also shown an increase in type 2 cytokines in serum as well as in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Tissue hybridization studies have shown that patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have higher levels of type 2 cytokines and lower levels of type 1 cytokines in surgical lung biopsy specimens than do patients with normal tissue. These cytokine imbalances suggest that idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is associated with overexpression of type 2 cytokines and the inhibition of type 1 cytokines.Other data support a central role for IFN-gamma. In idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, isolated fibroblasts demonstrate basal levels of collagen messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) transcription and synthesis of protein. This basal function is markedly reduced by IFN-gamma.15 Additionally, patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have levels of IFN-gamma in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid that are inversely related to the level of procollagen III, which is a marker of ongoing fibrosis.16 This association suggests a possible relationship to disease progression Although it is intriguing, the type 2 hypothesis does not fully explain lung fibrosis. For example, asthma is also associated with elevated levels cytokines. Finally, pulmonary fibrosis in patients with progressive systemic sclerosis occurs in the absence of an isolated increase in levels of type 2 cytokines.TGF-beta is also thought to play a key role in IPF. It is known that TGF-beta causes an increase in fibrosis in various organs. Also, when TGF-beta is overproduced in mouse lungs, an aggressive and progressive fibrosis is seen. It is interesting that TGF-beta is antagonized by IFN-gamma via an increase in Smad7. Bleomycin causes a brisk lung fibrosis in mice, but it can be inhibited by increased production of Smad7. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS The signs and symptoms of all the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias are similar and it is difficult to confidently diagnose patients on these traits alone. However, each disease has a general pattern at presentation and knowledge of these can guide a physician in evaluating the patient Patients classically present with exercise-limiting dyspnea as their primary complaint. Many also have a troublesome nonproductive cough. The appearance of any unusual symptoms such as constitutional complaints or symptoms related to connective tissue disease or occupational exposures should prompt further investigation. Basilar dry rales are typically prominent in all types of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Clubbing can be seen in all patients, but it is most common in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Evidence of right ventricular failure, such as right ventricular heave, an accentuated pulmonic second sound, or peripheral edema, may be seen in the late phase of any idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. A prolonged expiratory phase or wheezing is suggestive of RB-ILD or concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis usually occurs in patients who are beyond 50 years of age. NSIP patients are typically younger, and patients with RB-ILD and DIP pathology are the youngest of all (mean ages: 36 and 42 yr, respectively). Past tobacco use greatly increases the risk of IPF and current use is necessary for a diagnosis of RB-ILD and DIP. Idiopathic BOOP occurs in middle-aged patients, more often in nonsmokers. When lymphocytic interstitial disease associated with collagen vascular disease, gammopathy, or human immunodeficiency virus infection is excluded, idiopathic LIP is extremely rare. Therefore, little is known about this disorder, and some authors even dispute its existence. Patients are sometimes treated with steroids prior to a full diagnostic evaluation and the response can be predictive of the specific type of disease. Patients with IPF are classically unresponsive to a steroid trial, while those with other types of pneumonitis frequently improve. DIAGNOSIS When idiopathic interstitial pneumonia is suspected or possible, consideration should be given to ruling out nonidiopathic causes first. Once this has been accomplished, further testing in patients who have an idiopathic cause typically reveals radiographic abnormalities and restrictive lung physiology, with a decrease in diffusion capacity. History: Given the wide variety of diseases and exposures that are associated with interstitial lung disease, the history is critically important in the evaluation of a patient who may have idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. The history should elicit information on cough and dyspnea and symptoms of connective tissue disease. The time of onset, the duration, and the cadence of symptoms may help narrow the diagnostic possibilities. Patients should be asked about significant occupational exposure to materials such as asbestos and silica. In addition, it is important to take a careful medication history to look for agents that may be associated with drug-induced lung disease. A focused review of systems is necessary to rule out interstitial lung disease associated with systemic disorders, most commonly the connective tissue diseases. Physical Examination: The physical examination of patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia is nonspecific. Crackles on examination of the chest are very common. Clubbing and evidence of cor pulmonale are late signs of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Except for ruling out known causes of interstitial lung disease, the physical examination is rarely diagnostic. Imaging Studies: Plain chest radiographs are usually nonspecific. They often show reticular or reticulonodular opacities in association with reduced lung volumes. Recent studies have shown that in expert hands, high-resolution computed tomography (CT) of the chest reduces the need for surgical lung biopsy. For example, high-resolution CT can suggest a specific diagnosis in a patient who exhibits the classic pattern of IPF, and it may obviate the need for a lung biopsy. Characteristics on high-resolution CT scanning that suggest IPF include reduce lung volumes, subpleural fibrosis predominantly in basilar areas, traction bronchiectasis . The fibrosis may be early, manifest as only irregularity of the pleural-parenchymal border in basilar areas without large areas of fibrosis or volume loss, or may end end-stage with extensive honeycomb formation. Abnormalities that argue against IPF and suggest another, perhaps inflammatory, diagnosis include presence of central ground glass attenuation, absence of fibrosis, and lack of traction bronchiectasis . Some patients will have both fibrosis and ground glass attenuation. If fibrosis is the dominant pattern and the ground glass occurs in the same area as septal fibrosis, the patient likely has IPF with micro-honeycombing. If however, the ground glass pattern dominates then alternative diagnoses should be considered. The CT features of IPF Biopsy Analysis : Bronchoscopy Transbronchial biopsy specimens obtained via bronchoscopy are too small to allow for a diagnosis of a specific idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. On the other hand, bronchoscopic biopsy can help rule out infection, granulomatous disease, and malignancy. In patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, elevated levels of neutrophils or eosinophils in the bronchoalveolar lavage suggest a rapid disease progression. These findings likely represent evidence of end-stage fibrotic lung disease rather than its pathogenesis. Thoracoscopy For those patients in whom radiologic and minimally invasive testing fails to yield a specific diagnosis, it is necessary to perform a surgical lung biopsy. The thoracoscopic approach is generally well tolerated, even in significantly impaired patients. It is best to take specimens from two or three sites. The specimen should not be taken from areas of the lung that appear to exhibit end-stage honeycombing on CT because the pathologic results will be nonspecific. It is better to biopsy areas that exhibit ground-glass opacities or even those areas that appear to be normal on high-resolution CT because tissue taken from these sites may demonstrate earlier pathology. THERAPY Diseases Other Than Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis:No randomized controlled trials have been published on the treatment of diseases other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Treatment is empiric. Steroid therapy (0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg/day) is usually advised when reversible changes are seen on biopsy. Steroids should be administered for several months, and then tapered as the disease resolves. Fortunately, survival rates are good for most patients, and some even achieve a complete recovery. If symptoms and/or radiographic abnormalities should recur, the patient will usually respond to an increase in steroid dosage.Patients who experience a recurrence are maintained on a prolonged course of a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agent usually cyclophosphamide or azathioprine. Patients with a NSIP-fibrotic variant have a worse rognosis, and they are usually treated first with a steroid followed by a cytotoxic or antifibrotic agent (IFN-gamma). Smoking cessation is mostbeneficial for patients with RB-ILD and DIP; their lung function may also improve with 6 to 12 weeks of steroid therapy. Even so, many patients with RB-ILD never regain normal pulmonary function; their activities are limited as a result of their respiratory dysfunction, although the dysfunction is rarely fatal. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Steroids The most commonly prescribed initial treatment is corticosteroid therapy, begun at a moderate dosage (eg, prednisone 0.5 mg/kg/day X 6 wk). However, corticosteroids have not been proven to prolong survival or improve pulmonary function among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. At best few patients will demonstrate a physiologic or subjective improvement usually a reduction in cough. Very few patients will show any significant improvement in pulmonary function parameters, and even in those who do, the benefit is usually transient. Cytotoxics In an effort to improve outcomes, the American Thoracic Society recently recommended that a cytotoxic agent (azathioprine or cyclophosphamide) be prescribed as a first-line drug in combination with a steroid. Antifibrotics Antifibrotic agents hold promise for directly inhibiting disease progression without causing immunosuppression, although the results of initial studies have been disappointing. Despite early excitement, colchicine and D-penicillamine have failed to show significant benefit in follow-up trials. Pirfenidone, a unique, investigational antifibrotic agent, was recently shown to have some potential benefit in a small phase II trial, and follow-up studies are ongoing.22 IFN-gamma IFN-gamma might be beneficial in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.