Bob Perelman, "Must Works of Art Reflect Only

advertisement

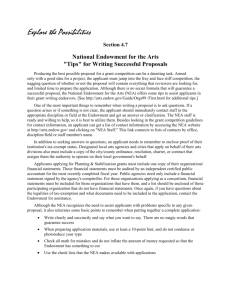

Bob Perelman, "Must Works of Art Reflect Only Marketplace Values?" (The Philadelphia Inquirer, Sunday, February 5, 1995) Government by irritation: It's one of the dominant political modes of our day. Taking their cuefrom talk-show hosts, politicians try to topple their opponents by unleashing discontent. Thesedays, the National Endowment for the Arts serves as a handy source of annoyance if not outrage: A few well-publicized examples of troublesome art have, over the last few years, been able It's not easy to argue against such energy. The value of art is not always instantly apparent - and at the same time the difficulties art brings with it are much more likely to be perceived at a glance. The latest remarks by senators that the NEA be abolished unless it supports "family values" show how true this is. Rather than arguing for art that is familiar, obedient and at best ornamental, I think art is valuable to the community precisely because it's not perfectly predictable or obedient. That doesn't mean that unruly art is automatically wonderful. Art is one of the testing grounds between individuals and the community. The point is that it's an opportunity for judgment: Members of the community need to make up their minds about it. That's one of the basic values of art. It can't be approached dogmatically. If the NEA budget is considered in terms of the $1.5 trillion federal budget, it's hardly a big deal, amounting to a relatively piddling $167 million, a fraction of a percent. The military spends more on marching bands. To eliminate the NEA would save each American exactly 65 cents a year the cost of a can of soda. Here in Philadelphia, dance, poetry, the visual arts and theater would all suffer; the gamut of organizations affected would range from the Institute for Contemporary Art to the Please Touch Museum, from the Philadelphia Orchestra to the Settlement Music School. The bigger, more established concerns would take a hit, but would probably survive. Some of the smaller organizations might have to close. Those who are out of sympathy with the arts might think that's fine: If a theater company needs a handout to survive there's something wrong with it. But to consider the arts in such a framework is an unfair oversimplification. For one thing, business itself is not treated in such a sink-or-swim way. Government subsidies are an integral part of many industries, from farming to sports franchises. One of the better reasons for such subsidies is that they shield enterprises from momentary reverses. If farmers couldn't survive a single bad season, it would ultimately make for a weak social fabric. With the arts, the time frame is often more stretched out. It can easily take decades for general taste to approve of development in art. The last hundred years are full of examples. In France painters such as Claude Monet and Henri Matisse were ridiculed by the majority of their contemporaries and there was a riot at the premier of Igor Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring." Of course, paintings by Monet and Matisse are now among the most valuable objects on the planet; and 30 years after it had driven listeners into a frenzy of disgust, Stravinski's music was used by Disney as the soundtrack to the dinosaur section of Fantasia. These are examples of successes. But its not always the case that today's innovative art becomes tomorrow's classic. A 1920s symphony by George Antheil that used airplane engines has not yet become a cultural treasure (nor is it likely to). That's important. It raises the point to say "Fine, innovate, be creative, but only if you turn out to be Monet. No duds or wild excesses, please." But why should the government have to underwrite art? Didn't Monet work on his own? There are a couple of answers to this. For one thing, a significant part of NEA money goes to community groups, often helping get art to places it doesn't normally reach: smaller towns, rural areas, schools that don't have the resources for art programs. And for the government to cut all arts funding would mean that it recognizes no values other than the marketplace. Under the reign of purely economic motives, there is no way anyone would want to produce something unless it could be sold immediately. Imagine a society in which every cultural product had to turn a profit instantly. If you want to get a sense of how claustrophobic this can be, consider how commercial television is dominated by spinoffs and imitations. Given how informative, exciting and revealing the arts can be, what an important antidote they are to instant opinion polls, and how essential they already are to different parts of the community, I think they're worth 65 cents a year. The money is not wasted: People in the arts are appreciative of the little support they get and work hard whether or not they get it. By their very nature, the arts speak to the individual's judgment at the same time as they offer possibilities for building communities. They're perfect training for the independence and possible sense of connection that we need to live in a democracy. Maybe 65 cents is a bit low. Why not make it $1.30? , 16-Mar-1999 09:07:25 EST