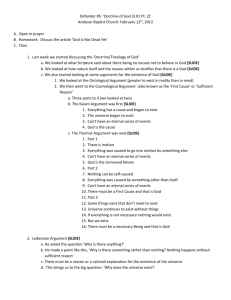

3. the first cause (cosmological) argument

advertisement