The words of swords

advertisement

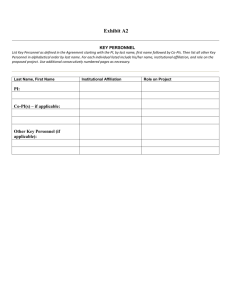

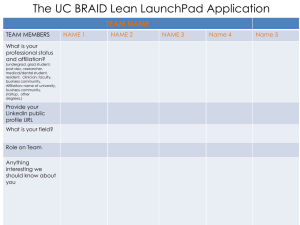

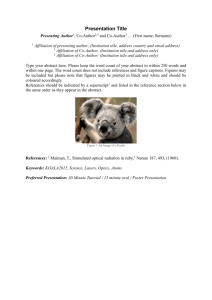

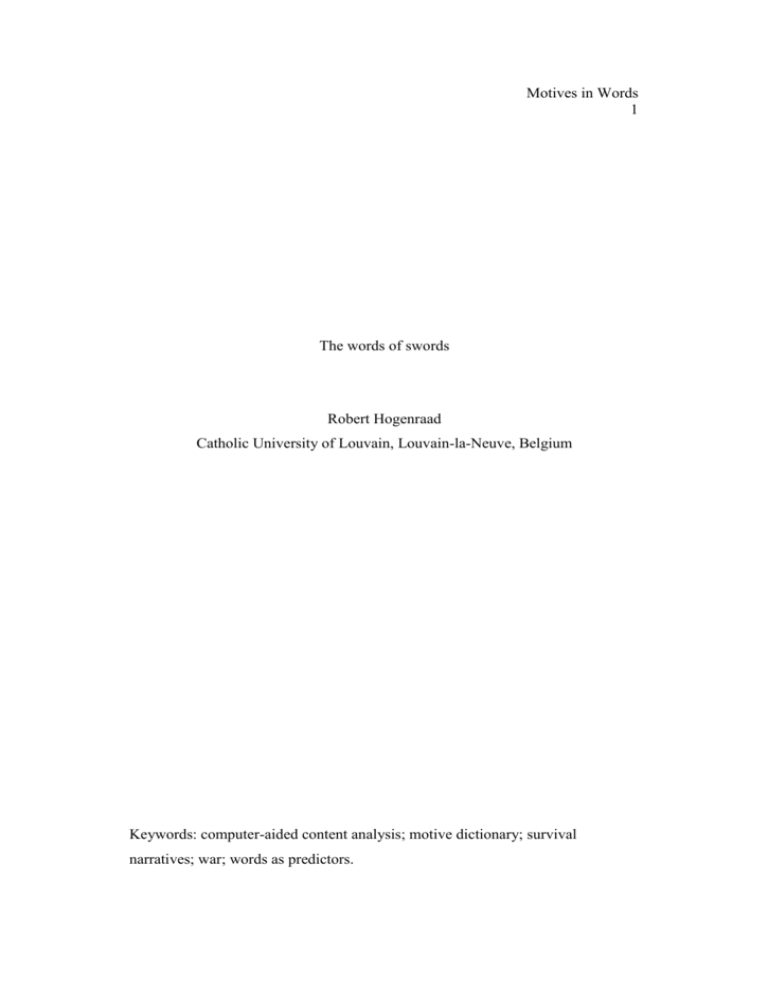

Motives in Words 1 The words of swords Robert Hogenraad Catholic University of Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium Keywords: computer-aided content analysis; motive dictionary; survival narratives; war; words as predictors. Motives in Words 2 Abstract McClelland predicts that when scores of low affiliation and high power coincide in political texts, violent events occur some time later. This coincidence, he calls “the imperial motivation”, i.e., the use of one’s own accumulated power to save the others, even against their will. With the help of PROTAN, a computer-supported content analysis system, and of a new computer-readable dictionary meant to assess the rates of affiliation and power in texts, one analyzes four types of survival narratives in order to test out the theory of imperial motivation on literary texts. Even with this version 1.0 of the new dictionary, one can verify that “the imperial motivation” is at work in literary texts as well. Motives in Words 3 The words of swords What this paper’s essential subject is concerns the interactions between two motives, the Need for Affiliation, and the Need for Power. A quick foreword should suffice to give traffic signals to readers to get the core meaning of this project. The project is enough exciting that it cries out loud for the one thing it lacks: it is unfinished. The will to power (or to conquer) counts among the major myths of modernity, i.e., from the 16th century to quite nowadays. Barbarism was described by Bartolomé de Las Casas in 1556 in “The Black Legend”: “Estirpar y raer de la haz de la tierra” [(As for those that came out of Spain, boasting themselves to be Christians, they took two several waies) to extirpate this Nation from the face of the Earth, the first whereof was a bloudy, unjust, and cruel war which they made upon them: a second by cutting off all that so much as fought to recover their liberty, as some of the stouter sort did intend)1. The will to power climaxed in the Nazi period; here, one has the choice among many quotations: “Es mußte der schwere Entschluß gefaßt werden, dieses Volk von der Erde verschwinden zu lassen” [The difficult decision had to be taken to make this people disappear from the earth] (Heinrich Himmler, Speech at Posen, October 6, 1943)2. The will to power is not limited to the roughage of terror and genocides. It extends to the myth of survival, and its accompanying survivor’s guilt and anxiety, leading many survivors to commit suicide, as did Primo Levi for one, in April 1987: surviving Auschwitz, surviving as a hostage in Beirut in the late 80's, or surviving after a shipwreck on a deserted island, requires always imposing one’s will on a hostile environment. The will to power is present also in the myth of alchemy (as the glorification of the art of imposing one’s will on matter in order to transform it); Goethe’s “Faust” (1808/1999) is the epitome of the will of eternal knowledge3. McClelland (1975b) has developed a theory that analyzes the Need for Power as well its interactions with another motive, the Need for Affiliation. The best definition of the Need for Affiliation lies in Forster’s passage “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country”, this in the section “What I believe” of E.M. Motives in Words 4 Forster’s 1951 “Two cheers for democracy”. This motive is close to McAdams’ 1982 notion of need for intimacy, as “when one is concerned with establishing, maintaining, or restoring a positive emotional relationship with a person, or simply likes or wants to be liked by someone else” (from the TAT test scoring guidelines in http://uwf.edu/coehelp/wbi98/wnast/class/fifteen.htm). And finally, in the introduction to Platonov’s (1999/2001) novel “Happy Moscow”, Eric Naiman comments about “individual ascetics who love the whole of humanity so much that they are ashamed of intimacy with another person” (p. xxii), this about the pseudo-collective pleasure parodied in the novel. The Need for Power refers to the impact one wants to have on another person, as by getting or keeping control over somebody else. The following extract from William Golding’s “Lord of the flies” illustrates this need: “(Memories of) the knowledge that they had outwitted a living thing, imposed their will upon it” (1954, p. 74, underlining mine); this sentence comes after the boys succeeded to kill a wild pig on the uninhabited island on which they were stranded after a plane crash. McClelland (1975b, in particular chapter 9 “Love and power: The psychological basis of war”, pp. 314-359; see also McClelland, 1975a ) goes one step further and argues that when the Need for Power in political texts is increasing while the Need for Affiliation or intimacy is decreasing, one can predict that brutal and violent events, such as wars, rebellions, and various forms of revolt, will occur within some time after. The coincidence of low affiliation and high power, he calls “the imperial motivation”4, i.e., the use of one’s own accumulated power to save the others, whether they liked it or not. Both McClelland (1975b) and Winter (1993) have accumulated evidence in this sense. Analyzing the imperial motivation in the fields of economy and politics is the ultimate purpose of this project. Many would urge social scientists to do so, and the sooner the better. However, one suspects that reality –that is, the news you hear or see in the media for example– is not that transparent: Constraints of all sorts, censorship, incomplete or false information, not to mention disinformation or strategies of deception, make it difficult to assess reality with clarity. On February 10, 2002, “The Sunday Times” titled on page 5 “Dostoevsky can teach you about terror”, this about screenwriter Tony Marchant saying, after filming “Crime and Motives in Words 5 Punishment”, that “our present crisis is all there”. And in the foreword to an English translation of Gogol’s “The Government Inspector”, Sergei Mashinsky has it that “For a large portion of the 19th century literature in Russia was the only legal platform for impassioned protests against the tyranny of the ruling landowning class” (Gogol, 2000, p. 7). By and large, if imperial motivation possesses any psychological reality, it could be easier to put one’s finger on it in the analysis of fiction than in the analysis of a real event (Handelman, 1985; Hogenraad et al., 2002). Four literary exemplars were content analyzed: two survival narratives (Willam Golding’s 1954 “Lord of the Flies”, and Daniel Defoe’s 1791 “Robinson Crusoe”), one alchemist narrative (Goethe’s 1808/1999 “Faust”), and one narrative of transformation –as a variant of an alchemist narrative–, Franz Kafka’s (1916/1996) “The Metamorphosis”. Method Literary texts Golding’s novel was scanned, the other narratives were secured from the Gutenberg database http://www.promo.net/pg/. “Lord of the Flies” is William Golding's best-known novel. It is the story of a group of boys who, after a plane crash, set up a fragile community on an uninhabited island. As memories of home recede and the blood from frenzied pig-hunts arouses them, the boys' childish fear turns into something deeper and more primitive. At first, they enjoy the freedom of the situation but soon divide into fearsome gangs which turn the paradise island into a nightmare of panic and death. “Lord of the Flies” is composed of 12 chapters, accounting for 61,709 words, of which 5,520 are different words. Pruning declensions reduces the number of different words to 3,518. “Robinson Crusoe” (Defoe, 1791/1994) recounts the story of a stranded sailor, seemingly alone on an island, who rediscovers himself through resilience and spirit, until his meeting with Man Friday (whom he rescues from a most certain death). The narrative was divided into its 20 chapters. The narrative makes up 121,232 words, of which 6,190 are different. Thus figure comes to 4,688 after pruning. Motives in Words 6 Goethe’s “Faust” describes a man making a pact with the devil (alchemy), yet, more than that, it is also a survival narrative (Wood, 2000) –through resignation and renouncement (“Stirb und werde”)–, as in the words of The Lord in the “Prologue in Heaven”: “A good man in his darkest aberration, /Of the right path is conscious still”5 (the full résumé of Faust’s complex story is available at http://www.levity.com/alchemy/faust.html. The 33 scenes of “Faust” (Part 1 and 2) are composed of 63,609 words and 8,185 different words (6,716 after pruning). Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” is the parable (of alienation, of humility) about a man, Gregor Samsa, who wakes up one morning transformed into a giant insect. Although ostracized by his family, Gregor manages to keep a positive relationship with his sister (at least for a time), yet dies in the end. The short story was divided into 25 segments each of the same number of words, 886, except the last segment (894 words), making a total of 22,258 words, 2,876 different words, and 2,142 after pruning) Content analysis Changes in the two motives in the corpuses were assessed with the help of the PROTAN content analysis system (Hogenraad, Daubies & Bestgen, 1995). Among other things, PROTAN allows using a categorizing procedure for analyzing the content of a text. This procedure is based on semantic dictionaries. Categorizing words is a quasi-experimental procedure in the sense that, having selected a list of relevant words –such as a list of abstract words–, we compare all the words of the text to all the words of a dictionary. A dictionary, in textual analysis, is no more than a list of words organized into categories. When we apply a dictionary to a text, we are merely looking for matches between a word in a dictionary and a word in a text: We count the number of word matches in each category and take the percentage of the number of word matches. The motive dictionary The motive dictionary rests on three pillars which are the Need for Achievement (N-Ach), the Need for Affiliation (N-Aff), and the Need for Power (N-Pow). It is built from several sources: the Philip Stone's General Inquirer Motives in Words 7 categories (version IV) (see the General Inquirer home page http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~inquirer) (Stone et al., 1966), to which were added some categories of Colin Martindale's Regressive Imagery Dictionary (1975), some categories of the Lasswell value dictionary (Namenwirth & Weber, 1987; see also the General Inquirer home page), and a few words from David Heise's 1965 article "Semantic differential profiles for 1,000 most frequent English words" that had not yet been included in the main motivation dictionary. Several words of these categories were modified or deleted, while other ones were added, so as to stay as close as possible to McClelland's theoretical frame of reference. Elias Canetti's (1960) "Crowds and Power" was also a useful resource of items for elaborating the power motivation categories. The motivation dictionary is built so that a word assigned to one category cannot be present in another one except the superordinate category to which its category belongs. N-Ach makes up 887 entries in the dictionary, N-Aff, 622, and N-Pow, 1,068 (Table 1). INSERT TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE Results “Lord of the Flies” After correction for autocorrelations (Hogenraad, McKenzie, & Martindale, 1997), N-Aff exhibits a U-shaped profile as in Figure 1 [R² = .45, F(2, 9) = 3.7, p < .06], while N-Pow exhibits the opposite one [R² = .80, F(1, 10) = 35.38, p < .0001]. The correlation between the observed scores of N-Aff and N-Pow is -.73 (n = 12, p = .007, with confidence interval running from -.91 to -.26). INSERT FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE “Robinson Crusoe” In “Robinson Crusoe”, N-Aff unfolds as a U-shaped curve [R² = .70, F(3, 16) = 12.65, p < .001], and so does N-Pow [R² = .42, F(2, 17) = 6.08, p < .05]. However, here, the correlation between affiliation and power (observed scores) is .74, (n = 20, p = .0001, confidence interval running from .44 to .89) (Figure 2). Motives in Words 8 INSERT FIGURE 2 ABOUT HERE “Faust” No significant profile could be uncovered for N-Aff, but a positive linear trend was uncovered for N-Pow (not shown here) [R² = .23, F(1, 33) = 9.12, p < .01]. Yet, the correlation between the observed values of N-Aff and N-Pow is -.49 (n = 33, p = .004, confidence interval running from -.71 to -.17). “The Metamorphosis” An opposite picture (Figure 3) appears when one analyzes Kafka’s “Metamorphosis”, i.e., affiliation goes upward, even if moderately, while power goes downward [R² = .24, F(1, 23) = 7.42, p < .05 for affiliation, and R² = .23, F(1, 23) = .23, p < .05]. However, the correlation between affiliation and power is non significant. INSERT FIGURE 3 ABOUT HERE Discussion In Figure 1 (“Lord of the Flies”), the inverse relationship between power and affiliation is almost perfect until chapter 7, that is, at the point where the group breaks down and new affinities are recreated between the boys, causing the affiliation curve to go up again. At the opposite, in “Robinson Crusoe”, the relationship between affiliation and power is positive (and also significant). But in this latter case, the survival narrative does not develop into a major conflict, as it did in “Lord of the Flies”. Of the four stories, “Robinson Crusoe” is the only one that ends for sure in a positive way: Robinson is saved; it is also the only survival story in which the correlation between affiliation and power is positive. In the other three stories (“Lord of the Flies”, “The Metamorphosis”, and “Faust”), the issue is rather negative: death occurs in all; and the correlations between affiliation and power are negative in all cases (even if power declines steadily in the Kafka’s short story6, contrary to what happens in the other three stories). Even Faust dies blind, Motives in Words 9 and frustrated, after struggling with Baucis and Philemon, –only to have his soul saved quite near the end by the Angels playing a trick on Mephisto; yet here too, the correlation between affiliation and power is negative. For those who wish to think further about the idea, the following suggestion, in the form of a quotation from Primo Levi’s (1958/2001) “If this is a man”: “Survival without renunciation of any part of one's own moral world (...) was conceded to very few superior individuals” (p. 98). Motives in Words 10 Notes 1. On Bartolomé de Las Casas’ defense of the Indians, see http://www.gonzaga.edu/faculty/campbell/enl310/casas.htm 2. For a collection of quotations from officials of the Nazi regime on the fate of the Jews, see http://www.holocaust-history.org/nazis-words/. 3. For alchemy narratives, see http://www.levity.com/alchemy/ 4. Tzvetan Todorov (2000) recently coined the expression of “la tentation du bien” (the temptation of the good) which is even closer to the idea of using one’s power to save the others. Todorov’s book has been translated into Spanish [“Memoria del mal, tentación del bien”. Península: Barcelona, 2002], but not yet into English. 5. “Ein guter Mensch, in seinem dunklen Drange, Ist sich des rechten Weges wohl bewusst”. 6. The recurrent negative force (“le moi haïssable”) of Kafka’s characters –and their acquiescence in a totalitarian nightmare (Chamberlain, 2002, p. 23)– is repeated in a recent novel “Insect dreams” (Estrin, 2002) where Kafka’s hero, Gregor Samsa, is given a rich life ahead. Motives in Words 11 Acknowledgment Acknowledgment is made to the National Fund for Scientific Research, Belgium (Grant no. 1.5.061.02, 2001-2002). Reprint requests should be addressed to Robert Hogenraad, Psychology Department, Catholic University of Louvain, 10 Place du Cardinal Mercier, B-1348 Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgium); e-mail Robert.Hogenraad@psp.ucl.ac.be Motives in Words 12 References Bartolomé de Las Casas (1656). The Tears of the Indians: Being an historical and true account of the cruel massacres and slaughters of above twenty millions of innocent people; committed by the Spaniards... London: J.C. for Nath. Brooke Canetti, E. (1960). Crowds and power. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux. Chamberlain, L. (2002, March 15). The Faustian roach [Review of Marc Estrin’s “Insect Dreams”]. The Times Literary Supplement, 23. Defoe, D. (1791/1994). Robinson Crusoe. London: Penguin. Estrin, M. (2002). Insect dreams. New York: Bluehen. Forster, E. M. (1951). Two cheers for democracy. London: Arnold. Goethe, J. W., von. (1808/1999). 'Faust': The first part of the tragedy (John Williams, Trans.). London: Wordsworth. Gogol, N. (2000). The government inspector and selected stories (Christopher English and Gordon McDougall, Trans.). Moscow: Raduga Publishers. Golding, W. (1954). Lord of the flies. London: Faber and Faber. Handelman, S. A. (1985). Fragments of the rock: Contemporary literary theory and the study of Rabbinic texts –a response to David Stern. Prooftexts, 5, 75-103. Heise, D. R. (1965). Semantic differential profiles for 1000 most frequent words in English. Psychological Monographs, 79, 1-31. Hogenraad, R., Daubies, C. & Bestgen, Y. (1995). Une théorie et une méthode générale d'analyse textuelle assistée par ordinateur. Le système PROTAN (PROTocol ANalyzer) (Version du 2 mars 1995) [A general theory and method of computer-aided text analysis: The PROTAN system (PROTocol Analyzer), Version of March 2, 1995]. Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgium), Psychology, Catholic University of Louvain. http://www.upso.ucl.ac.be/protan/protanae.html Hogenraad, R., McKenzie, D. P., & Martindale, C. (1997). The enemy within: Autocorrelation bias in content analysis of narratives. Computers and the Humanities, 30, 433-439. Hogenraad, R., McKenzie, D. P., & Péladeau, N. (2002, in press). Force and Motives in Words 13 influence in content analysis: The production of new social knowledge. Quality and Quantity, 36. Kafka, F. (1916/1996). The metamorphosis and other stories. London: Dover Publications. Levi, P. (1958/2001). If this is a man (Stuart Woolf, Trans.). London: Abacus. Martindale, C. (1975). Romantic progression: The psychology of literary history. Washington, DC: Hemisphere. McAdams, D. P. (1982). Experiences of intimacy and power: Relationships between social motives and autobiographical memory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 292-302. McClelland, D. C. (1975a). Love and power: The psychological signals of war. Psychology Today, 8, 44-48. McClelland, D. C. (1975b). Power: The inner experience. New York: Irvington Publishers. Namenwirth, J. Z., & Weber, R. P. (1987). Dynamics of culture. Boston: Allen & Unwin. Platonov, A. (1999/2001). Happy Moscow (Robert Chandler and Elizabeth Chandler, Trans.). London: Harvill. Stone, P. J., Dunphy, D. C., Smith, M. S., & Ogilvie, D. M. (1966). The General Inquirer: A computer approach to content analysis. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press. Todorov, T. (2000). Mémoire du mal, tentation du bien: Enquête sur le siècle [Memory of the evil, temptation of the good: Enquiry on the century] . Paris: Robert Laffont. Winter, D. G. (1993). Power, affiliation and war: Three tests of a motivational model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 532-545. Wood, M. (2000, 20 July). The man without predicates. London Review of Books, 22, 11-13. Motives in Words 14 Table 1. Categories and subcategories of the motive dictionary Category Subcategory N. of words Examples and roots Achievement 887 Instrumental 115 labor, market Need** 52 craving, wish Goal** 39 aim, merit Try** 82 competitive, risk Means** 161 expedient, plan Persist** 39 constant, lasting Complete** 36 founder, success Finish** 60 erase, quit Means*** 39 cost, equip Fail** 107 default, flounder Transaction gain*** 67 accretion, boost Transactions*** 89 install, release behavior* Affiliation 622 Affection* 67 mate, sweetheart Social behavior* 86 answer, escort Affiliation** 330 accompany, couteous Affect loss*** 10 alone, indifference Affect participants*** 62 dad, mistress Affect words 42 family, nostalgic Positive affect*** 26 affable, thoughtful Power 1068 Power** 551 ambition, justice Power gain*** 23 emancipate, nominate Power loss*** 44 captive, weak Power ends*** 8 plead, recommend Power conflicts*** 154 adversary, invade Motives in Words 15 Power 60 arbiter, reciprocal 52 patriarch, detective 32 emissary, orator Power doctrine*** 21 conservatism, dogmatic Power authority*** 24 legitimate, reign Residual power 99 colonialism, terrorize cooperation*** Power authoritative participants*** Power ordinary participants*** words*** * RID subcategory; ** Harvard IV subcategory; *** Laswell subcategory Motives in Words 16 Figure captions Figure 1. Need of Affiliation (N-Aff) and Need for Power (N-Pow) (observed and fitted) in the 12 chapters of William Golding’s “Lord of the Flies”. Figure 2. Need of Affiliation (N-Aff) and Need for Power (N-Pow) (observed and fitted) in the 20 chapters of Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe”. Figure 3. Need of Affiliation (N-Aff) and Need for Power (N-Pow) (observed and fitted) in the 25 segments of Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”. Motives in Words 17 Figure 1. Need of Affiliation (N-Aff) and Need for Power (N-Pow) (observed and fitted) in the 12 chapters of William Golding’s « Lord of the Flies ». Motives in Words 18 Figure 2. Need of Affiliation (N-Aff) and Need for Power (N-Pow) (observed and Fitted) in the 20 chapters of Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe”. Motives in Words 19 Figure 3. Need of Affiliation (N-Aff) and Need for Power (N-Pow) (observed and fitted) in the 25 segments of Kafka’s «The Metamorphosis»