Evolving innovation proficiency with a corporate mind

advertisement

Evolving innovation proficiency with a corporate mind

Machiel Emmering, Walter Baets

Nyenrode University, NOTION

Straatweg 25

3621 BG Breukelen

The Netherlands

email: {m.emmering}{w.baets}@nyenrode.nl

Abstract

Many innovations fail, and as innovation is required for organizational survival, organizations

should improve their capacity to do it. Scientific

support has limited practical value, as it is too

normative and simple, it does not account enough

for individual differences, and the body of

knowledge is highly dispersed, which imposes

problems on selection. A scientific way to support

the individual organization is by means of a corporate mind, consisting of a memory and a reflexive

capacity. The memory can support first order innovation, by helping to ‘remember’ what seemed

(not) to work well within a certain frame of the innovation practice. The reflexive capacity can support second order innovation, by facilitating a critical but productive reflection on the frame in

which the organization innovates, as to optimize

innovation trajectories case by case, rather than

adopting one single innovation frame.

1

Introduction

This is a position paper of a research on innovation. The

research aims at making a practical model annex methodology by which organizations can learn to develop their

proficiency with respect to new product development

(NPD), as to make NPD trajectories more efficient, and to

increase the chance of a product’s success. It will try to

overcome the shortcomings of former research on innovation, thereby contributing to the body of knowledge. § 2

sets out what problem is addressed. This is done from the

practical point of view in § 2.1, as to address why it is

indeed a problem. In § 2.2 it is done from the theoretical

point of view, as to address what science has done up till

now, and what can be improved. § 3 focuses at the research: in § 3.1 it is set out what the research tries to accomplish; in § 3.2 it is set out how this initially will be

approached. In section § 4 an attempt is made to support

some credibility.

NOTION is Nyenrode’s sponsored research institute

for Knowledge Management and Virtual Education

2

Innovation as a problem domain

2.1

Innovation in practice

Assessment of the success of strategic innovations - i.e.

the ones that are new to the company as well as to the

world - yields a rather heterogeneous picture. A combined research e.g. by Ernst & Young, AC Nielsen and

Global Client Consulting states that 5% of all innovations

is successful, while other research by AC Nielsen in the

same year (1999) shows that 10% is successful, whereas

Hultink [1998] states that about 60% of innovations succeed. From these differences two preliminary conclusions

can be drawn: success is an equivocal notion, and / or the

way of measuring influences the outcomes. It seems that

different methods, variables and norms affect the outcome thoroughly. From this it follows that judging success is in itself a problematic exercise. A third conclusion

derives from comparison of the outcomes: although results vary highly, it is clear that a great part of all attempts to innovate successfully fails.

A low capability to innovate successfully is not just an

inconvenient loss of investments; it is a flaw that threatens viability, specifically on the somewhat longer term.

Viability means being capable of maintaining one’s identity (in the first place: existence) independently of similar

organisms within a shared environment [Beer, 1989]. For

organizations this means that they have to obtain and

maintain an adequate fit with their environment. Thereto

they have to produce the behavior and output that is to be

supported by a critical mass of relevant stakeholders. This

support can come from e.g. political, ideological, or legal

sides, but specifically important for commercial organizations is support from the market. The market is by nature

subject to change to some extent. New technologies and

products from other companies, the economic climate,

scientific breakthroughs, cultural and fashionable preferences and whatever more may lead to changes in market

needs. And when the environment changes, the conditions underlying a certain fit with that environment in

terms of the capability to fulfil market needs may also

have changed. This means that in order to restore or to

improve the fit that leads to viability, an organization will

have to be equipped with a capacity to change itself. It is

therefore not surprising that Langerak et al [2000] found,

that there is a significant correlation between on the one

hand the expertise to innovate and the success of new

products, and on the other between success of new products and organizational success. So organizational success (i.e. viability) depends to an important extent on

proficiency with respect to product innovation.

Considering that innovations fail often, and that they are

crucial to organizational viability, it makes sense that the

Marketing Science Institute has proclaimed product innovation, or NPD, to be a research domain of top priority

[Hultink, 1998]. This raises the question in what respect

science has contributed to NPD up till now.

2.2

Innovation in Academia

Innovation / NPD is in itself of course not a new topic of

investigation. Innovation as a general term can apply to

several subjects, such as products, processes or markets.

Our primary interest is in product innovation. NPD can in

a narrow sense be seen as a part of a product innovation,

if literally understood as the activity of creating a new

artifact. In a broader sense however NPD and product

innovation are synonyms; activities such as marketing are

then also taken into account. This is the sense in which

NPD is used in the research. Scientific contributions on

NPD are abundant. Hands-on help typically comes from

phase models that try to offer grip on NPD-projects, by

setting out which steps are to be taken. Examples are:

Ulrich and Eppinger [1995] – design, manufacturing,

marketing; Marquis [1969] – recognition, idea formulation, problem solving, solution, development, use; or

Christiansen [2000] – idea generation, funding, development (launch, post launch). These models are sometimes

elaborated per phase. When the available resources are

appropriately distributed, and when one observes discipline in execution, such models should be helpful. Of

course, it is in these models neither known, nor considered relevant what the product is. The assumption is that

for any innovation some general activities and development phases can be identified. Therefore the activities

and phases are expressed in abstract terms, like the ones

mentioned above. The elaboration, number and detail of

phases, activities, or sub-output may differ, but categorizing them, one can discover three general phases of NPD:

variety amplification, variety reduction, and coupling. In

the first phase, variety in terms of what could be done is

created. This phase ends with the choice for a concept of

a product. In the second phase, variety in terms of what

will be done is reduced. This is done by the execution of a

functional decomposition of the job to be done, coupled

to a time-frame that also contains the moments on which

to make specific choices for further crystallization. The

output of this phase is the product. In the third phase,

what has been done must enter the world, in order to

generate the fit that (re)assures the company’s viability.

The output of this phase is the marketed product. This

corresponds with Langerak’s [et al, 2000] classification

of theoretically modeled steps in pre-development, development and commercializing activities. Abstract phase

models provide generic insight in innovation as a process,

allowing one to acquire basic innovation expertise, or to

prepare NPD-activities, as ‘checklists’ that assure that all

basic stages have been thought of. A first critique on such

theory is that the categories are too general to be of practical value. Van de Ven et al [2000] go after thorough

research much further in their critique. They conclude

that phase models are too simple, linear, normative and

theoretical. There is a persistent mismatch between such

theory and reality.

Other literature offers the widest range of specific topics.

For (probably) every phase, activity, line of business,

discipline, and whatever dimension one can think of,

some literature with a scientific approach is written to go

in detail. The large amount of literature and its highly

varying quality obscures a proper overview of the field of

innovation, which troubles selection. Moreover, as the

contributions have a more or less general character, the

relevance will have its limit. Nelson and Winter [1977]

conclude that these two observations are the fundamental

problems of theory of innovation: the body of knowledge

on innovation lacks an integrative framework, so that

individual contributions about a specific topic appear to

be arbitrary, and theory does not account for individual

differences.

We now can see that the problems of scientific support

relate to quality, specificity and relevance. The limited

specificity and relevance of scientific support is in its

very nature, as science cannot account for singularities,

when it comes to describing how innovation works. As

Beer [1989] says, science is a variety reducing activity. It

tries to uncover invariant properties of the phenomena

under study by means of homomorphic mapping; it does

not give isomorphic descriptions of all the cases that were

studied. So invariant characteristics are derived from the

omission of all that is singular, thereby transcending individual, specific, contingent situations. It is however exactly that situation in which the innovator would like to

be supported. In that respect, apart from the problem of

quality, science has intrinsic restrictions in helping an

innovation manager to identify what is relevant, let alone

in offering possible solutions that account for his specific

situation. This means that the NPD-manager remains

dependent upon himself with respect to his own situation.

Taking a particular innovator’s earlier experiences and

specific situation as a starting point, this research will try

to develop a model that accounts for these problems of

relevance and specificity.

3

Research attempt

3.1

Problems of innovating

Now that it is clear what the research aims at both in the

practical as well as in the academic sense, it is time to

assess what the model ought to support. This has to do

with invariant problems of innovation.

Organizational operations are about producing something

in a certain way; about what and how. The more experience and insight there is in dealing with a specific what

(product) and how (process), the more crystallized are the

conditions under which to come to the best products and

processes, thus to satisfying effectiveness and efficiency.

Routine operations are controlled by organizational functions, structures, practices and means that have been chosen for having proved to work in an assumed optimal

way. The in that order prescribed business process can be

seen as a coherent unity of embedded decisions, which

provide the organization with a capacity of routine regulation. Organizing an innovation trajectory is more difficult: the process of innovation requires to some extent

non-routine regulation, as an immanent feature of innovation is, that what and how are at least to some extent not

clear yet. The more strategic and thus the newer the innovation is, the less there are equivalents of the thing to be

developed that could serve as an example, and thus the

less there are references in what and how exactly to develop. In this process of inventing future reality, the organization is the only responsible party for making decisions required for doing so. As has been shown, this ends

up more frequently in failure than in success. Nevertheless organizations realize (whether explicitly or implicitly) that it is crucial to viability, so that they have to do it.

Moreover, the more important innovation is against the

background of the competitive environment, the stronger

one will probably realize that the innovation preferably

should be distinctive within that environment. A strategic

innovation initially yields a monopoly on it. But success

entails competitors’ mimetic behavior (a basic rule of

economics), diminishing the market potential of one’s

successful original. So the harder it is to copy the product, i.e. the more the new product is tied to competencies

characteristic for the organization that invented it, the

better. The innovator’s dilemma is now clear: in order to

remain viable, one has to initiate practices that put one’s

overall strength of viability at stake. It then becomes

clear, that innovations are experiments with viability, as

Achterbergh [1999] puts it. In this experimental function,

the organization must make decisions that give direction

and progress to innovation. It is not clear in terms of efficiency how the organization can best get to a certain

point, nor is it clear in terms of effectiveness if this point

will support its viability. If the proficiency and decisions

are inadequate, the risk of ineffectiveness or inefficiency

of the innovation project increases, resulting in respectively developing the wrong thing or developing a thing

in the wrong way.

Unpredictability of the future and inexperience with activities never carried out before point to risky uncertainty

as the core problem of NPD. The basis for sensible behavior dealing with uncertainty is a cognitive capacity,

that allows for accurate simulation of the situation beforehand in the form of planning, and adequate selection

of behavioral options in the real situation, as to control.

The behavior that shapes the course and appearance of

the innovation is crucial, and this behavior is preceded by

decisions steering that behavior. Ideally, these decisions

match project requirements with organizational resources.

Therefore, knowledge inducing the best decisions can be

seen as a fundamental condition to be successful in innovation. Such knowledge should be at a project manager’s

disposal. Those in charge of NPD have on the account of

their proficiency as managers certain a priori ideas about

how to approach a specific innovation and how to deal

with it while it evolves. But however good project managers have proven to be, they will always face limitations

concerning relevant knowledge. Categorizing the field of

mental capacities in terms of specific subjects, one may

be:

1. consciously capable

2. unconsciously capable

3. consciously incapable

4. unconsciously incapable

Table 1: knowledge consciousness, based on Ayas, 1997

The category of knowledge in the first column is the

knowledge potential of the NPD manager, that gives him

the proficiency to operate on the basis of his expertise.

Under 1 are explicit distinctions, which are deliberately

involved in a manager’s decisions. This knowledge plays

an active role in considerations; it is about topics that are

explicitly paid attention to. In this category, the manager

‘knows what he knows’.

Under 2 are implicit distinctions, which are unconsciously involved in a manager’s decisions. This knowledge is

highly internalized, and the manager is not actively aware

of these distinctions as being the basis for certain decisions. To this extent, the manager acts on routine. In this

category, the manager ‘does not know what he knows’.

There is a limit to knowledge in all possible respects: one

could not have full insight in the organization’s available

capacities, in the organizational history of NPD experiments, etc. The knowledge flaws are categorized in the

second column.

Under 3 is problem awareness, which can be seen as

knowledge about or awareness of certain knowledge that

is missing in order to do something right. Knowing this,

one can try to obtain the missing knowledge (either by

learning it, or by involving someone having the required

knowledge). In this category, the manager ‘knows what

he does not know’.

Under 4 is the cognitive blind spot, as Von Foerster

[1984] calls it. This is the situation in which the manager

is not aware that he misses specific knowledge that could

lead him to better decisions. In this category, the manager

‘does not know what he does not know’.

So, under 3 the problem is ‘not knowing’, but this problem is limited, in the sense that the fact that it is clear that

some knowledge is missing implies that some light is

shed on what knowledge to look for to overcome this

problem. Under 4 however the problem is not ‘not knowing’, but ‘not knowing about not knowing’, in other

words, not knowing that you have a problem.

Now, in order to complement a manager’s NPD proficiency and the project information that is available as to

make the most satisfactory decisions, he might be served

by means that help him to acquire relevant knowledge

(category 3), and that make him aware of possibly relevant knowledge that he had not thought of (category 4).

With such an instrument, one can optimize decisions, e.g.

about possible action when faced with a problem, or

about establishing the best possible organization in the

NPD-project, both by which the proficiency in NPD practices is amplified. This knowledge may be derived from

experiences of the company that are recognized as relevant corporate knowledge. That would make the

knowledge base characteristic for the company. It could

be seen as the company’s mind, facilitating the manager

to draw upon the organization’s memories that may be

relevant for his situation. In more systemic terms it means

facilitating a subsystem to make use of the larger system’s variety potential. This implies, as Baets [1998]

says, that the process of decision-making rather than the

decision itself becomes the focal point of attention, which

has to do with learning and knowledge building.

This research is aimed at developing an instrument that

serves as a corporate ‘mind’. This mind would consist of

a memory and a reflexive capacity. The memory would

operate in order to recall what might be relevant in a specific situation and how the organization currently can

deal or earlier has dealt with that issue. The reflexive

capacity would help to be critical in a productive way

about NPD practices that are accepted as given. If management starts to extend its expertise with a corporate

mind, the company as a whole starts to build up a capacity to deal with complexity, in order to optimize its interaction with the environment on the basis of earlier experiences and on relevant knowledge available throughout

the company. Doing so, it starts to build a capacity that

continuously enhances the proficiency in NPD activities.

3.2

Initial approach of the research

The ideas of the research will be tested in a company in

fast moving consumer goods with the pseudonym Code.

Code has a mission to be an innovator, but also struggles

with an unacceptable failure rate; moreover NPD projects

proceed too often in a troublesome way. Code has established a standardized NPD process, so new products are

developed in an assumed best, fixed trajectory of specified steps.

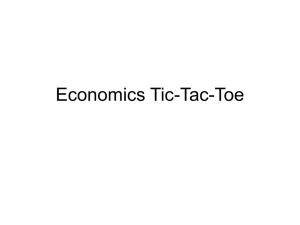

Project 1

Project 2

Project 3

Project 4

Result 1

Result 2

Result 3

Result 4

idea

concept

develop

Decisions are based on the one hand on explicit or implicit distinctions about what matters and what doesn’t, a

set of perceptions that differs to some extent per manager.

On the other hand, the decision on specific action depends on the behavioral options available, which suggests

knowledge of one’s own (organizational) capabilities, and

this is particularly problematic in large organizations.

Different perceptions of relevance and knowledge about

organizational capabilities lead to decisions that are likely

to yield different results, the ones being more desirable

than the others. If these ‘decision determinants’ are gathered and the more interesting are preserved, the basis on

which to come to decisions can be organizationally optimized. Therefore, to speak with Baets [1998], the need

for consolidation of perceptions in order to decide properly is evident. The broader the collective base of possibly

relevant distinctions, the broader the potential to come to

the best thinkable decision. So, development of a device

as a corporate mind, complementing managers’ ability to

make adequate decisions, based on distinctions that

proved (not) to be of relevance in some specific situation,

would be an adequate research-direction to follow, in

view of the earlier mentioned convocation to research

NPD. This device should support the manager’s proficiency in a scientifically sound way to be dependent upon

himself.

launch

market

= step of innovation trajectory

= experience per step

Figure 1: A model of application of Code’s NPD model

In this picture the (simplified) set of steps is depicted in

the boxes. Application of this approach to different NPD

projects leads to different experiences (ovals) per modeled step, yielding different overall results, as reality

proves.

In order to build a corporate mind that can recall these

experiences, the experiences have to be collected and

analyzed in terms that can be interpreted in an evaluative

frame of reference. The terms to be compared are any

variable that one chooses in order to describe experiences. This selection has to be limited, since not everything

can be described, nor is it relevant to remember everything. However it has to suffice to be of value, so we

have to be very prudent in our selection. An additional

problem of selection is the explanatory strength of the

relation between a variable chosen and the phenomenon

to be remembered. It may be that an outcome is (partly)

falsely ascribed to some variable, for instance because the

phenomenon in fact only occurred as a contingent ultimate rather than as a comprehensible immediate effect of

the variable. This is all too common: we know from chaos theory that small energy flows may have the largest

and most unpredictable consequences. Broader interpretation implies that influences generally reach further than

the direct environment and than intentions. This leads

some to state that everything is related to everything else,

so the search for causes and origins must be discontinued

[Kilduff and Mehra, 1997]. Although this viewpoint may

be too skeptical, it is clear that we have to be cautious

while identifying the variables that seem to matter most.

Two actions help to account for this problem. In the first

place we will identify variables from within Code, rather

than e.g. make an external selection of so called critical

success factors as described in the literature. Therefore

the variables relate to a specific organization by definition. In the second place, through time we will select the

more appropriate variables, along the co-evolving result

of innovating and learning.

Now, two of all possible reasons that the effectiveness

and efficiency of Code’s innovations are sub-optimal are:

1) One does not make the best possible use of Code’s

potentials to ‘fill in’ the modeled steps of the trajectory (sub-optimal performance within the frame);

2) The innovation model itself (the selection of what is

explicitly indicated as relevant) may not be the optimal one (sub-optimal performance of the frame).

Ad 1 Sub-optimal performance within the frame

Application of the model means creating settings, in

which in every step of every NPD project real people will

have to be doing real activities, to get to the best possible

result. Although the steps in all projects may be the same

on the abstract level of generalization, they will lead to

different experiences and results in their factual situation.

Experiences with (parts of) settings should be recorded in

such a way that allows one to evaluate them against (a)

result, (b) each other, (c) the variables in the modeled

setting. Evaluation of a (part of a) setting against result

means trying to rate its contribution to the project’s result. As success is usually measured by financial indicators, this evaluation will require a differentiation of an

overall evaluation as ‘success’ or ‘failure’, as such a statistical attribute does not clarify the contribution of a

specific variable such as somebody’s expertise to it.

Evaluation of the settings against each other makes it

possible to determine what appears to be the better setting

for a specific need within a project. The company can

consequently try to reinstall that setting in a new project.

Innovation then comes to follow an evolutionary trajecto-

ry, selecting step by step the best known setting as recorded in the corporate mind, thereby optimizing the use

of an organization’s potential. Evaluation of the settings

against the NPD model means that the experiences obtained per step of the model in return may say something

about that model, thereby feeding its refinement. This

would lead to sophistication of the organization’s NPD

model and obtained experiences by ever better use of inhouse capabilities in terms of the explicit organizational

innovation distinctions, in a continuous upward spiral.

So an instrument that helps to systematically gather, analyze and feed back experiences would allow a company

to optimize the use of its in-house capabilities, in terms of

the variables in which the experiences are described. This

is the organizational memory. The conscious employment

of specific capacities, following from building and applying this organizational memory will enhance proficiency

in NPD projects in that specific organization, as the experiences and capacities are the organization’s own. The

expression of a set of variables as factors that seem to be

successful for that company thus may lead to a set of

‘idiosyncratic generalizations’, a hard to copy set of specific competencies and comparative advantages. Protracted development of the corporate mind leads to tailormade science for the individual company.

This part of NPD, about making the best possible use of

capacities, is about optimizing a road to innovation with

the help of a memory. It can be seen as first order innovation. The research is in the first place aimed at designing

this instrument.

Ad 2 Sub-optimal performance of the frame

The general model in use describes a more or less fixed

approach to develop new products. It expresses the organizational distinctions about how to innovate, and thus

functions as a norm for project management. This model

is accepted as given. As different theories and practices

apply different sets of distinctions (meaning that they

apply different norms), it may be said that innovations

can be developed along different valid trajectories. It is

not unlikely that the one yields on average better results

than the other, which may also depend on specific typologies of organizations or environments, as Nelson and

Winter [1977] suggest. It may also be the case that NPD

projects should in fact not be approached in a standardized way at all, or that the organization should be better

of with a different general model. So apart from the

above-mentioned under-utilization of the organizational

potential within the frame of a standardized NPD model,

an entirely different reason for sub-optimal effectiveness

and efficiency of NPD projects can be that the frame of

distinctions to approach them with is in itself not optimal.

A company would thus be helped with an instrument that

supports a reflexive capacity to evaluate the model that

prefigures NPD projects, thereby assessing the organization’s assumptions underlying its approach of innovation

projects. The instrument should also facilitate this critical

reflection on the selected NPD model.

This part of NPD, about optimizing approaches of NPD,

is about innovating the road to innovation with a reflexive

capacity. It can be seen as second order innovation. The

research will develop the basic structure of an instrument

that supports evaluation and improvement of a company’s

assumed best predisposition of NPD projects.

4

Credibility

It may appear ambitious or contradictory that the aim is

to develop a model that has a practical value by accounting for individuals’ situations, while also overcoming

certain flaws of theory on innovation in general. This

indicates that some academic credibility is required.

Moreover, the approach may appear somewhat abstract.

This indicates that some practical credibility is required.

From the theoretical point of view, the research can be

located in the field of systems theory, cybernetics, and

related fields. More in particular, it will apply principles

of evolution. The idea is that if a way of doing proved to

be successful (in the different terms one could think of),

that way is reused in new projects. Doing so, the capabilities to act more accurately and to differentiate ways of

doing over different types of projects (rather than sticking

to one fixed phase model) may improve. Organizations

can try to create a positive feedback loop by building

forth on proven successes. The use of ideas of the fields

mentioned should assure academic rigor, while not losing

the requirement of individual application possibilities.

From the practical point of view, one of the outcomes

will be that lessons from NPD projects can be drawn, and

should be remembered in certain new projects. Project

teams should be given the lessons that give them the possibility to refine their approach, on the basis of what may

be relevant, and of what appeared (not) to work in the

past. This should eventually be done by the organization

itself, since the mind is to be filled with its own experience. The research is not that far. However, there is some

proof that the idea is appealing. Within Code, several

projects were analyzed and learnings were drawn. Recently a team was assigned for a new project that had

many similarities with two projects in the past that both

failed. I was invited to present the learnings that I considered relevant to the team. The team was highly enthusiastic and the overall opinion was that many issues would

probably not have been accounted for without that reflection on earlier experiences. An other piece of evidence is

that reflection upon a set of aggregated learnings made

Code to refine its NPD frame.

Concluding remarks

The research annex model under construction should

improve NPD success in practice, by supporting better

use of organizational knowledge within an NPD approach

and by improving that approach itself. The outline that

has been set out should account for the general problems

of specificity and relevance that more regular scientific

support entails. Both the first order and the second order

focus account for the specificity of individual situations,

with a mind of which the content is a specific organization’s own. The application area can be anything; the

choice to test in the field of NPD project management is

contingent. All in all, the result aimed at has in principle a

wide application range and is relevant for many systems

and types of problem areas.

References

[Achterbergh, 1999] Jan Achterbergh. Polished by Use. Eburon,

Delft, 1999.

[Ayas, 1997] Karen Ayas, Design for Learning for Innovation.

Eburon, Delft, 1997.

[Baets, 1998] Walter Baets. Organizational learning and

knowledge technologies in a dynamic environment. Kluwer,

Boston, 1998.

[Beer, 1989] Stafford Beer. VSM. In R. Espejo and R. Harnden

(eds.), The Viable Systems Model: Interpretations and applications of Stafford Beer’s VSM. Chichester, John Wiley &

Sons Ltd., 1989

[Christiansen, 2000] J.A. Christiansen. Competitive innovation

management, techniques to improve innovation performance.

MacMillan Business, 2000.

[Von Foerster, 1984] Heinz von Foerster. Principles of selforganization - In a socio-managerial context. In H. Ulrich, G.

Probst, Self-organization and the management of social systems: Insights, promises, doubts, and questions. Springer

Verlag, 1984.

[Hultink, 1998] Erik Jan Hultink. Do’s en Don’ts van

Productintroducties. In E.J. Hultink (ed.), Productintroducties. Kluwer, Deventer, 1998.

[Kilduff and Mehra, 1997] M. Kilduff and A. Mehra. Postmodern and Organisational Research. In Philip J. Dobson, Longitudinal Case Research: A Critical Realist Perspective, Systemic Practice and Action Research, vol 14, nr 3, 2001.

[Langerak et al, 2000] Fred Langerak, Erik Jan Hultink, Henry

Robben. The Mediating Effect of NPD-Activities and NPDPerformance on the Relationship between Market Orientation

and Organizational Performance. http://www.ideas.uqam.ca/

ideas/data/Papers/dgreureri200051.html.

[Marquis, 1969] D.G. Marquis. The anatomy of successful

innovations. In M.L. Tushman and W.L. Moore (eds.), Readings in the management of innovation, second edition, Ballinger Publishing Company, Cambridge, 1988.

[Nelson and Winter, 1977] R.R. Nelson and S.G. Winter. In

search of useful theory of innovation. Research policy 6,

1977.

[Ulrich and Eppinger, 1995] Ulrich and Eppinger. Product

design and development. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1995.

[Van de Ven et al, 2000] A.H. van de Ven, H.L. Angle, and

M.S. Poole, editors. Research on the Management of Innovation – The Minnesota Studies. Oxford University Press, 2000.

![Your [NPD Department, Education Department, etc.] celebrates](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006999280_1-c4853890b7f91ccbdba78c778c43c36b-300x300.png)