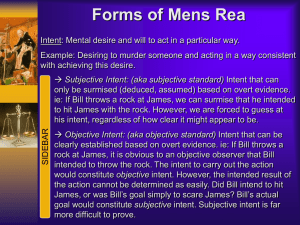

Letters of Intent Should They Be a Thing of The Past

advertisement

CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Maximum Period 4 Hours LETTERS OF INTENT By Roger Knowles Letters of Intent Letters of Intent Essence of a Letter of Intent To establish that a contract has been concluded not only requires evidence of agreement by the parties on all the terms they consider essential, but also sufficient certainty in their dealings to satisfy the requirement of completeness. Letters of intent as traditionally drafted fail on both counts since they were usually incomplete statements preparatory to a formal contract coming into operation. For example having received tenders the employer would send a letter of intent to the contractor who had submitted the lowest price and whose tender was to be accepted in the following terms: We are pleased to inform you that your tender has been successful. Our lawyers are currently drawing up the contract which will be sent to you for signature within the next two weeks His Honour Judge Fay said in the case of Turriff Construction Ltd v Regalia Knitting Mills Ltd (1971) A letter of intent is no more than the expression in writing of a party’s present intention to enter into a contract at a future date. Save in exceptional circumstances, it can have no binding effect. With the passage of time however commercial procedures changed and the legal effect of letters of intent due to time pressures can as currently drafted have a binding effect. As we shall see the words or His Honour Judge Fay thirty years after they were made are no longer relevant. Instruction to Undertake Work In an ideal world all contracts should be properly drawn up and signed before work commences whether the contracts are between employer and main contractor or main contractor and subcontractor. It seems that in ever increasing instances this is not the case. Fast track construction methods often overtake the procedures for drawing up the contract, which in many instances lacks essential urgency. This applies in the construction sector and can often lead to disputes which prove time consuming and expensive to resolve. In many cases however the parties are anxious to make an early start even before all the key contractual matters have been agreed and long before a formal contract has been drawn up. In the absence of a formal contract it is now common practice for the employer to send the contractor a letter of intent which allows the contractor to make a start on site or to commence design or order materials. For example the employer may write a letter to the successful contractor in the following terms: “Please take this letter as an intention to enter into a contract. Our lawyers are in the process of drawing up a contract which will be sent to you for signature within the next two weeks. In the mean time please commence ordering the materials. In the event of no contract being finalised between us we undertake to pay all reasonable and proven costs” Letters of Intent As the contractor does not feel fully secure with only a letter of intent he is often reluctant to conclude formal subcontracts with his subcontractors. Anxious for some of the subcontract work to start work he sends letters of intent to some of the subcontractors. Does the Letter of Intent Create a Contract? Courts are often called upon to decide whether or not the wording in a particular letter of intent is sufficient to create a contract. In the case of British Steel Corporation v Cleveland Bridge (1984), Lord Justice Goff said: Now the question is whether in a case such as the present one any contract has come into existence must depend on a true construction of the relevant communications which have passed between the parties and the effect (if any) of their action pursuant to those communications. There can be no hard and fast answer to the question whether a letter of intent will give rise to a binding agreement; everything must depend on the circumstances of the particular case. The judge went on to say that if work is done pursuant to a request contained in a letter of intent it will not matter whether a contract did or did not come into existence because if the party who has acted on the request is simply claiming payment his claim will usually be based on a quantum meruit. Unfortunately this does not introduce certainty as there is no hard and fast rule as to what constitutes a quantum meruit payment and hence uncertainty will still exist. It is of limited advantage to a contractor or subcontractor to learn that he is entitled to a payment if there is no agreement as to how much the payment will be. From this decision it can readily be seen that even if a letter of intent includes a specific instruction to undertake work it does not necessarily mean that a contract has come into being. Reference to Standard Conditions Sometimes the letter of intent will stipulate that certain standard conditions are to apply. The case of Harvey Shopfitters v ADI (2004) is an example of how not withstanding reference to the application of standard conditions a confused situation can arise. Harvey Shopfitters tendered for some refurbishment work and were sent a letter of intent which referred to the standard conditions which were to apply namely the JCT IFC conditions. The letter of intent also included the contract price and the date for completion and the significant wording if for any unforeseen reason the contract should fail to proceed and be formalised then any reasonable expenditure incurred by you in connection with the above will be reimbursed on a quantum meruit basis. No contract was ever formalised but the work was undertaken as if there was one. Harvey Shopfitters claimed that as no formal contract had been entered into, in keeping with the wording in the letter of intent they were entitled to payment on a quantum meruit basis. The court disagreed and held that the parties may not have signed a contract but proceeded as if they had. Letters of Intent In the case of Bryen and Langley v Martin Rodney Boston (2004) a letter of intent included the following words: The contract will be executed under the Standard Form of Building Contract 1998 Edition Private With Quantities. Whilst a contract was drawn up it was never signed by the employer. The works were carried out but a dispute arose. It was held by Judge Seymour that despite the wording in the letter of intent the terms in the Standard Form of Building Contract did not apply. His reasoning was that the wording “the contract will be executed” in the letter implied that the execution of the Form was anticipated as a separate future event. Further there were blanks to be completed in the Appendix to the Form without which there could not be a workable agreement. Unresolved Matters It is often the case that whilst the letter of intent makes reference to standard conditions of contract there remains a number of critical matters still to be agreed. For example the parties may agree that a JCT Standard Building Contract With Quantities 2005 Edition was to apply but the sum for liquidated and ascertained damages is still be agreed or dates for possession and completion. There can however be an inconsistent approach by the courts as to whether in the light of matters which remain to be agreed there is a contract in being. It was decided in the case of Monk Building and Civil Engineering Ltd v Norwich Union Life Assurance Society (1993) that no contract had come into being since inter alia several of the contract terms, including the liquidated damages provision had not been resolved. The case of Mitsui Babcock Engineering Ltd v John Brown Engineering Ltd (1996) is another example of a dispute as to whether a contract had come into being. In October 1992 Mitsui Babcock Engineering Ltd sent a proposed form of contract to John Brown engineering Ltd which was subject to the MF/1 Conditions. Clause 35 of the condition which was headed “performance tests” was struck out and a marginal note” to be discussed and agreed” written in. The document was signed by both parties but there was no agreement concerning performance tests and liquidated damages for failure to achieve the performance tests. Despite the parties’ inability to reach agreement on these matters the court held that there was none the less a binding contract Signed Letter of Intent It is common practice for the parties to sign the letter of intent but this in itself does not mean that a contract has come into being. In the case of Ben Barratt and Son (Brickwork) Ltd v Henry Boot Management Ltd (1995) a letter of intent was sent by the main contractor Henry Boot which was signed and returned by Ben Barratt a subcontractor. The work involved brickwork on some halls of residence for the University of Manchester. Ben Barratt maintained that it commenced work on the basis of the letter of intent and that no formal contract was ever concluded. Henry Boot argued that there was a contract. The fact that the letter of intent was signed by Ben Barratt was not material to the decision. It was held that there was clear evidence that the parties intended to enter into a subcontract and no evidence to Letters of Intent support the contention that they did not intend there to be a subcontract until the main contract was signed. A signature on a letter of intent will therefore signify that the signor agrees to the contents of the letter but does not in itself indicate the letter constitutes a contract. If Contracts There are more varieties of wording in letters of intent than stars in the sky which makes it difficult to generalise as to their effect. Many give rise to disputes because there is no standardisation and each one has to be dealt with on its merits. When the parties fall out, usually in relation to payment, the court has to decide whether the wording is sufficiently explicit to form a contract. In the case of British Steel Corporation v Cleveland Bridge Ltd (1984) the court had to invent an “if” contract. This in essence provides that if the contractor carries out work as specified in the letter of intent the employer will make a payment. This is in no way a contract in the normal sense as it usually lacks the full details as to the extent of work which is required to be undertaken and all the terms which are to apply. Unfortunately whilst the letter of intent may include an instruction to undertake work, often it does not specify the manner in which payment is to be made. The parties are fairly relaxed as they both are under the impression that a formal contract will be produced reasonably quickly containing all the necessary terms and therefore there is no reason for concern. It is only when a sticking point is reached and no contract is agreed that the parties begin to argue as to the manner and amount of payment to be made. The courts often resolve this problem by holding that payment should be made on a quantum meruit basis which in essence means a sum which is merited by the work undertaken or in other word a fair and reasonable sum. This only leads to another problem being how much is a reasonable sum. Multiple Documents In some cases a letter of intent may represent only one of the documents which make up a contract. The case of Twintec Ltd v GSE Building and Civil Engineering Ltd (2003) is illustrative of a complex situation involving a quotation, letter of intent, acceptance letter and the minutes of a meeting, all of which when put together was held to constitute a contract. Use of the Term Subject To Contract “Subject to Contract” is a term commonly used by estate agents and usually signifies that a buyer has been found and the property is the subject of a sale but that the agreement is not binding until a contract has been drawn and signed. Case law however leads to the conclusion that when used in letters of intent the words “subject to contract” do not prevent a contract form coming into force before a formal contract is drawn up and signed. In the case of Fraser Williams (Southern) Ltd v Prudential Holborn Ltd (1994) it was held: In order to determine whether a contract had been concluded it was necessary to examine the course of dealing between the parties bearing in mind that the phrase subject to contract was normally used to prevent a party from being Letters of Intent contractually bound. However when used by experienced businessmen subject to contract is normally taken as meaning that acceptance must be in writing. On that basis the proposal was not an offer capable of being accepted. The inclusion of the words “subject to formal contract” in a letter of intent became the subject of a dispute in the case of Stent Foundations v Carillion Construction (Contracts) LTD (2000). It was held that as all the essential term of a contract had been agreed by the parties a contract came into being even though a formal contract was never signed. Where the words “subject to contract” appear in a letter of intent it does not always signify that the drawing up and signing of a formal contract is essential before a contract coming into force. Cap on Expenditure It is becoming popular for there to be a cap on expenditure included in the letter of intent. Where the cap is exceeded, which occurs more often than not, and the work comes to a halt for a variety of reasons, a dispute usually arises. The contractor expects to be paid the extra as he considers he has provided value. On the other hand the employer having inserted the cap sees no reason why more should be paid. The case of Monk Building and Civil Engineering Ltd v Norwich Union Life Assurance Society Ltd (1993) involved a dispute in relation to a letter of intent which included a cap on expenditure. A maximum expenditure figure of £100k was inserted in the letter of intent but in fact the total costs of the work undertaken came to some £4m. The parties agreed that extra work had been ordered since the letter of intent was sent. However if the letter of intent constituted a contract the contractor would have been entitled to payment in accordance with contract rates, which if applied would come to a total of much less than the £4m of contractors costs. It was held that as some of the essential terms of the contract had not been agreed no contract had come into being and therefore the contractor was entitled to payment of his costs. A slightly different story emerged in the case of AC Controls Ltd v British Broadcasting Corporation (2002) where the contractor was required by a letter of intent to undertake essential survey work and a financial cap on expenditure was fixed at £250k. Work proceeded beyond this figure and the contractor claimed a sum of £411k. The employer insisted that the capped figure only was payable. It was held that as the employer was entitled to determine the arrangement with the contractor when the cap was reached and failed to do so the contractor was entitled to be paid the full amount. In the case of Eugena Ltd v Gelande Corporation Ltd (2004) the claimant contractor was asked to submit a tender to undertake works for the defendant. The parties’ negotiations were on the basis that ultimately they would enter into a JCT Minor Works 1998form of contract. The defendant was keen to proceed with the works and before the contract was signed sent the defendant a letter of intent and paid a deposit of £40,000. The letter of intent authorised the claimant to carry out work up to a value of £50,000 exclusive of VAT. Work proceeded whilst the negotiations were in progress. The claimant became unwilling to proceed until certain matters were concluded particularly the finalisation of the contract. It was agreed that the claimant would stop work and leave the site. The claimant sent an invoice for £76,000 but the defendant refused to pay any more than the £50,000 value referred Letters of Intent to in the letter of intent. It was argued by the claimant that as the defendant had received £76,000 of value the full amount should be paid. It was held that the defendant was not entitled to recover for works which fell outside the scope of the preliminary or design work which fell outside the cap. A bizarre set of circumstances occurred in the case of Mowlem PLC v Stena Line Ports Ltd (2004) which arose out of the construction of a new ferry terminal at Holyhead in Anglesey. In this case the employer sent 14 letters of intent the last one dated 4th July 2002. The final letter of intent included a cap on expenditure of £10m but no formal contract was entered into. Due to the discovery of rock in the excavation and instructions for extra work being given by the Employer after the 4th July 2002 expenditure was incurred which well exceeded the £10m limit. The court held that the contractor was entitled to payment of only £10m as once this expenditure cap had been reached the contractor could have stopped work. From the above cases it can readily be seen that a cap on expenditure included in a letter of intent does not provide certainty that if the value of work undertaken exceeds the cap that payment will be limited to the capped amount. Is There an Entitlement to Profit? The wording in a letter of intent as to how the contractor or subcontractor is to be paid in the event of a contract not being concluded is important as it can severely effect the sums to which the contractor becomes entitled to be paid. In the case of Robertson Group (Construction) Ltd v Amey – Miller (Edinburgh) Joint Venture (2005). A letter of intent was sent relating to extensive refurbishment work at the Royal High School in Edinburgh under a PFI arrangement. The wording of the letter of intent comprised: We would request that you proceed with the Works forthwith upon the basis of this letter as your authority. Should a formal contract fail to be entered into for any reason other than the default or negligence of Robertson Construction then all direct costs and directly incurred losses shall be underwritten and reimbursed by the Joint Venture. We would state that the Joint Venture Partners shall be held liable Jointly and Severally for the commitments incurred by the Joint Venture under this agreement. A formal contract was never entered into and the parties became involved in a dispute over the interpretation of all direct costs and directly incurred losses The dispute related to whether the wording should be interpreted to include for profit. The court took the view that in the commercial world there is an expectation or at least a hope of returning a profit. A failure to make a profit would amount to a loss therefore as the letter of intent safeguards the claimant from making a loss then there existed an entitlement to be paid a profit. Letters of Intent The Right to Stop Work at Any Time A letter of intent as can be seen by the earlier examples given in this module may constitute a simple instruction to carry out work which in itself does not amount to a contract. The case of British Corporation v Cleveland Bridge (1984) offers a good example of a letter of intent which carried an instruction to commence the delivery of steelwork. As neither price nor contract terms were agreed no contract came into force. Either party could therefore at any time have served notice on the other terminating the arrangement without any financial liability other than payment of a reasonable price for the supply of the steelwork. In the case of Monk Building and Civil Engineering Ltd v Norwich Union Life Assurance Society (1993) the parties were in dispute as to whether a contract had come into being. If the answer had been in the affirmative then the parties could only terminate the arrangement in accordance with the terms of the contract. The dispute however related to the payment provision but none the less had there been an argument concerning termination the decision would have rested upon whether a contract had come into being or not. By way of summary if no contract has come into force as a result of the issue of a letter of intent then either party can terminate the arrangement at any time without incurring a financial liability. If however the letter of intent constitutes a contract the parties can only terminate the arrangement in compliance with the terms of the contract. Incorporation into a Formal Contract of Work Done Under a Letter of Intent A situation may arise where on receipt of a letter of intent the contractor commences work. Part way through the progress of the work the parties sign up to a formal standard form of contract. It is distinctly possible that the terms set out in the letter of intent vary in some marked manner from the terms in the formal contract which was ultimately signed by the parties. How are these conflicting terms to be reconciled? In the case of Trollope and Colls Ltd v Atomic Power Constructions Ltd (1962) the court held that work undertaken in accordance with the terms of a letter of intent would be governed by the contract ultimately signed. In this respect Judge Megaw said: So far as I am aware there is no principle of English law which provides that a contract cannot in any circumstances have retrospective effect or that if it purports to have in fact retrospective effect it is in law a nullity. Conclusion Perhaps we are all getting less formal in our commercial dealings or we are so anxious to get underway that we let formal procedures take a back seat. It seems clear however that if the parties are prepared to start work before all the essential terms have been agreed and committed to writing then they must be prepared for disputes over payment to arise if the negotiations regarding contract terms stall. It must be obvious from the few examples given above the use of the letter of intent is fraught with danger. Most contracts commence on the basis that the work will proceed without too many difficulties. Relationships are usually excellent before work starts and it seems therefore perfectly normal for work to commence following the Letters of Intent sending of a simple letter with a formal document to follow. Unfortunately when unexpected expenditure comes along the relationships can become stained and agreement more difficult to secure. It is at this point that both parties begin to feel that it was a mistake to start work without a proper formal contract being in place. Letters of Intent TEST QUESTION AND ANSWERS TEST QUESTIONS Question 1 What was the purpose of the traditionally worded letter of intent? Question 2 If a letter of intent sent to a contractor or subcontractor includes merely an instruction to carry out work with no reference to payment, what financial entitlement to payment does the contractor or subcontractor have? Question 3 What type of work is normally instructed to be undertaken in a letter of intent? Question 4 What is the effect of a letter of intent being signed by a contractor or subcontractor? Question 5 If a letter of intent stipulates that particular standard conditions of contract are to apply will those conditions form the basis of a contract? Question 6 What significance do the words “subject to contract” or “subject to formal contract” have in a letter of intent? Question 7 What is the effect of including a financial cap in a letter of intent? Question 8 Where work commences following the issue of a letter of intent what rights do the parties have to terminate the work. Letters of Intent Question 9 If work commences in accordance with an instruction contained in a letter of intent and partway through the progress of the work a formal contract is drawn up and signed in terms which differ from those in the letter of intent is the work governed by the terms in the letter of intent or the formal contract Letters of Intent MODEL ANSWERS Question 1 The traditionally worded letter of intent was no more than an expression of the writer’s intention to enter into a contract at some future date. Question 2 Where a letter of intent includes an instruction to undertake work the contractor’s financial entitlement will be to receive a payment based upon quantum meruit. This is a payment which the work merits or in other words a fair and reasonable payment. This was illustrated in the case of British Steel Corporation v Cleveland Bridge (1984). Question 3 It is normal for a letter of intent to include an instruction for work to be commenced, design work to be undertaken or materials to be ordered. Question 4 If a contractor or subcontractor signs a letter of intent it signifies agreement to all the matters referred to therein. It does not mean that a contract comes into being as this will be dependant upon the wording in the letter of intent. Question 5 The reference in a letter of intent to standard conditions of contract may signify that they are to apply to any work which is carried out by a contractor or subcontractor pursuant to receiving the letter. This was the situation in the case of Harvey Shopfitters v ADI (2004) where reference was made to the JCT IFC conditions. However in the case of Bryen and Langley v Martin Rodney Boston (2004) it was held that wording “The contract will be executed under the Standard Form of Building Contract 1998 Edition Private With Quantities” did not ensure that these conditions applied to the work carried out. It was held in this case that wording “the contract will be executed” which also appeared in the letter of intent implied that the execution of the form was anticipated as a separate future event. Further there were blanks to be completed in the Appendix to the Form without which there could be no workable agreement. Letters of Intent Question 6 The use in commercial contracts of the wording “subject to contract” or “subject to formal contract” usually indicates that until a formal document is signed no contract comes into being. However case law has shown that where used in letters of intent these words may have a different meaning. In the case of Stent Foundations v Carillion Construction (Contracts) Ltd (2000) the court held that as all the essential terms of a contract has been agreed by the parties a contract had come into force even though the letter of intent included the words “subject to contract”. By contrast in Fraser Williams (Southern) Ltd (1994) the court held that the phrase “subject to contract” in a letter of intent precluded a contract from coming in to being. There is therefore no hard and fast rule as to the significance of the wording “subject to contract” when included in a letter of intent. Question 7 The are varying interpretations as to the effect that a cap on expenditure may have when included in a letter of intent as can be seen from the following legal decisions 1. In the case of AC Controls Ltd v BBC (2002) a financial cap of £250,000 was placed on expenditure. The contractor however carried out work up to a value of £411,000. It was held that it was a matter for the employer to determine the arrangement once the cap had been reached and his failure to do so resulted in him having to pay the full amount. 2. In Eugina Ltd v Gelande Corporation (2004) the letter of intent authorised expenditure up to £50,000. It was held that the contractor was not entitled to recover the over expenditure of £26,000. 3. In Mowlem PLC v Stena Line Ports Ltd (2004) it was held that the contractor was only entitled to payment of the £10m cap included in the letter of intent as he should have stopped work once the cap had been reached. It can be seen that it is financially risky for contractors or subcontractors to exceed the financial limit included in a letter of intent. Question 8 The financial liability of the parties who wish to terminate an arrangement set out in a letter of intent depends upon whether the letter of intent in itself or as part of a series of documents constitutes a contract. If no contract comes into being either party is at liberty to terminate the arrangement at any time. If this occurs payment for the work undertaken in accordance with the letter of intent will be due but there will be no financial liability arising from the termination. If on the other hand a contract comes into effect as a result of a letter of intent then a termination of the arrangement must be carried out in accordance with the terms of the contract. Letters of Intent Question 9 It was held in the case of Trollope and Colls Ltd v Atomic Power Construction Ltd (1962) that a contract when drawn up and signed can have retrospective effect. Therefore if work is commenced following the receipt of a letter of intent and subsequently a formal contract is signed the condition of the formal contract will govern the work undertaken in accordance with the letter of intent as well as the work carried out under the formal contract. Letters of Intent