kinetics and equilibrium studies of removal of methylene blue by

advertisement

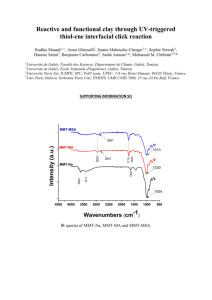

1 2 3 ADSORPTIVE REMOVAL OF METHYLENE BLUE DYE BY MELON HUSK: KINETIC AND ISOTHERMAL STUDIES 4 Olajire, A. A1*; Giwa, A. A1 and Bello, I.A2 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 1 Industrial and Environmental Chemistry Unit, Department of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso – Nigeria 2 Physical Chemistry Unit Department of Pure and Applied Chemistry, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso – Nigeria 17 ABSTRACT 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 The adsorption capacity of Methylene blue (MB) dye from aqueous solution onto raw melon husk (RMH) was investigated under various experimental conditions. Batch studies were performed to evaluate the effect of various experimental parameters such as contact time, initial concentration of MB dye and dosage of RMH on the efficiency of the sorption process. Optimum conditions for MB dye removal were found to be at an adsorbent dosage of 8.0 g/L of solution for an equilibrium time of 120 min. Equilibrium isotherms for the adsorption of MB dye on RMH were analyzed by Freundlich, Langmuir and Temkin isotherm models and the goodness of fittings were inspected using linear regression analysis (R2) and sum-of- square-error (SSE). The equilibrium data were well described by Langmuir and Temkin equation at all range of operating parameters. Lagergren, Elovich and Morris – Weber equations were employed to study kinetics of sorption process. The sorption process was very rapid at the initial stage as 80% of the dye was removed within the first 5 mins. The kinetics of the adsorption followed pseudo – second order model with R2 values ranging from 0.999 to 1 for all initial dye concentrations studied. Keywords : Melon husk, isotherm, kinetics, methylene blue dye, adsorption. 35 36 37 38 *Author for all Correspondences, E-mail<olajireaa@yahoo.com> 39 Tel: +2348033824264 40 41 42 1. INTRODUCTION 43 There are several methods which can be used to treat dye wastewater. These include 44 biological, chemical and physical1. All these methods were found inefficient and 45 incompetent because of the stability of the dye towards light, oxidizing agents and 46 aerobic degradation. Among these methods, adsorption is widely used for its maturity and 47 simplicity. Of different adsorbent materials, activated carbon is the most popular for the 48 removal of pollutants from wastewater. However, its widespread use is restricted due to 49 high cost2. As such, numerous alternative materials have been investigated to adsorb dyes 50 from aqueous solution, using Methylene Blue as the model basic dye, such as guava leaf 51 powder3, dehydrated wheat bran carbon4, diatomaceous silica5, wheat shell6, NaOH- 52 treated pure kaolin7, bamboo charcoal8, silver fir (Abies amabilis) sawdust9 and activated 53 carbon from sugar beet molasses10. 54 Basic dyes are the brightest class of water soluble dyes used by the textile 55 industries, and Methylene blue is one of the most frequently used dyes in all industries11. 56 It dissociates into cation and chloride ion in aqueous solution12. Presence of this dye in 57 water leads to various health effects like eye burns, and irritation to the gastrointestinal 58 tract 59 methamoglobinemia, cyanosis and dyspnea, if inhaled directly. It may also cause 60 irritations to the skin7,13. with symptoms of nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. It may lead to 61 Two important physicochemical aspects for the evaluation of adsorption processes 62 as a unit operation are the adsorption equilibria and the adsorption kinetics. Equilibrium 63 relationships between adsorbent and adsorbate are described by adsorption isotherms, 64 usually the ratio between the quantity adsorbed and that remaining in the solution at a 2 65 fixed temperature at equilibrium. In the study of adsorption isotherm, linear regression is 66 frequently used to determine the best-fitting isotherm. The linear least-squares method 67 with linearly transformed isotherms has also been widely applied to confirm experimental 68 data, and isotherms using coefficients of determination. However, such transformations 69 of non-linear isotherms to linear forms implicitly alter their error structure, and may also 70 violate the error variance and normality assumptions of standard least squares14,15. It has 71 been reported that bias results from deriving isotherm parameters from linear forms of 72 isotherms, for example, Freundlich parameters producing isotherms which tend to fit 73 experimental data better at low concentrations and Langmuir isotherms tending to fit the 74 data better at higher concentrations16. Moreover, it has been also presented that using the 75 linear regression method for comparing the best-fitting isotherms is not appropriate17. 76 The advantage of using the non-linear method is that there is no problem with 77 transformations of non-linear isotherms to linear forms, and also they had the same error 78 structures when the best-fitting isotherms are compared18. 79 In this study, melon husk, an agricultural waste material, was used as the adsorbent 80 for its zero-cost and convenient acquisition in local markets. A non-linear method of 81 three widely used isotherms, the Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin, were compared in an 82 experiment examining Methylene Blue adsorption onto melon husk. The data have also 83 been explained on the basis of kinetic models. 84 85 86 87 88 89 3 90 91 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 92 93 2.1 Preparation of adsorbent 94 95 The melon husk used in this work was obtained from Aaradaa Market, a popular 96 farm produce market in Ogbomoso, Southwestern Nigeria. Debris and other relatively big 97 foreign materials were hand-picked from the husk, after which it was thoroughly washed 98 with distilled water, to remove soil and dust, drained and sun-dried. The dried material 99 was then ground, sieved into different particle sizes, and stored in air-tight containers as 100 raw melon husk (RMH) adsorbent. 101 102 103 2.2 Adsorbate 104 Methylene blue (Color index (C.I), 52015; λmax., 664 nm; molecular weight, 105 355.90), a cationic dye, used in this study was obtained in commercial purity (M & B 106 Laboratory Chemicals), and was used without any further purification. 107 108 109 N H3C N CH3 N S + CH3 Methylene blue; C.I, 52015 110 111 CH3 Cl Mol. weight, 355.90 4 .3 H O 2 112 A stock solution of the dye was prepared by dissolving an accurately weighed 113 quantity of the dye (1.000 g) in deionized distilled water (ddH2O) to make a 1000 mg/L 114 solution. The experimental solutions of desired concentrations were prepared by 115 accurately diluting the stock solution with ddH2O. 116 117 2.3 Batch studies 118 For each study, a 25 mL of MB dye solution (of varying concentrations, ranging 119 from 5 to 500 mg/L) was prepared in a 250 mL leak-proof reaction bottles and a varying 120 amount of adsorbent, ranging from 0.025 to 0.75 g, was added to each bottle. The bottles 121 were tightly fixed in a horizontal shaker (SM 101 by Surgafriend Medicals) and the 122 shaking proceeded for 2 hrs to establish equilibrium, after which the mixture was left to 123 settle for ten minutes, and then filtered. 124 The absorbance of the filtrate was determined with UV–Visible Spectrophotometer 125 (Genesys 10 UV-VIS Scanning Spectrophotometer) adjusted at λmax (664 nm) of MB dye. 126 By referring to the calibration curve of the dye, the corresponding concentration of the 127 dye in the equilibrium solution was obtained. The percentage removal of MB dye and 128 equilibrium adsorption uptake, qe (mg/g) was calculated using the following 129 relationships: 130 131 132 133 % Sorption qe 100 (Co Ct ) Co (Co Ce )V m (1) (2) where q e is the amount of MB dye adsorbed (mg/g) at equilibrium; Co and Ct are the initial concentration (at t = 0) and its concentration at time t = t (mg/L); m is the mass of 5 134 135 RMH (g); V is the volume of MB dye (L). 2.4 Error functions 136 The most common way to validate the isotherms is by inspecting the goodness of 137 fit using linear regression coefficients, R2. The R2 in the range of 0.9 to 1 indicates that 138 the isotherms have a satisfying agreement to the particular adsorption system in which the 139 value close to 1 is highly desirable. However, an occurrence of the inherent bias resulting 140 from the linearization might affect the final judgment. Therefore, an additional non-linear 141 regression error function has been considered to further validate the applicability of the 142 tested isotherms. 143 The sum-of-square-error (SSE) provides a better fit at the higher concentration 144 data as the magnitude of errors and the square of the errors increase with an increment in 145 concentration19. The mathematical formula of SSE used in this study is given by the 146 following equation20, 21. SSE 147 (qe, exp . qe, cal. ) 2 / N 148 where 149 qe cal is the amount of sorbate adsorbed at equilibrium calculated from the model (mg g-1), 150 qe,exp is the equilibrium value obtained from experiment (mg g-1) and N is the number of 151 data points. 152 153 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 154 The adsorbent prepared from raw melon husk (RMH) was studied for dye 155 adsorption and the results, thus obtained, were analyzed for the sorption efficiency of dye 156 from aqueous solution, under different experimental conditions. The results of the studies 157 are explained in the following sections. 6 158 159 3.1 Effect of sorbent dosage 160 161 The effect of sorbent dosage on MB dye-sorption by RMH was studied (Fig.1) by 162 varying adsorbent dosage from 0.025 g to 0.750 g in 25 mL of 50 mg/L solution of the 163 MB dye while keeping other parameters (contact time, agitation speed, particle size, 164 temperature) constant. 165 As evident from Figure1, the adsorption capacity (qe) decreases with increasing 166 adsorbent dosage. However, percent sorption increases very rapidly from 90.19 to 167 99.66% as the dosage of RMH was increased from 0.025 g to 0.200 g and stays almost 168 constant up to 0.750 g of sorbent dosage. An increase in the sorption with the sorbent 169 dosage can be attributed to greater surface area and the availability of more adsorption 170 sites22, 23. At higher dosage, however, the incremental dye sorption becomes low, as the 171 surface dye concentration and MB dye solution come to equilibrium with each other. 172 173 174 175 3.2 Effect of the initial concentration of MB dye 176 shown in Figure 2. Adsorption capacity (qe) increases with increasing initial 177 concentration of MB dye. The increase in the initial concentration of the dye enhances the 178 interaction between the MB dye molecules and the surface of the adsorbent24. For 179 instance, an increase in the initial concentration of the MB dye from 5 mg/L to 500 mg/L 180 led to an increase in adsorption capacity (qe) from 1.249 to 47.38 mg/g. There was, 181 however, a corresponding decrease in percent sorption from 99.89 % to 37.91 %. Similar The effect of the initial concentration of MB dye on the adsorption by RMH is 7 182 observation had also been reported by others22, 25, where decrease in percent sorption with 183 increasing initial concentration of sorbate resulted in increased adsorption capacity. 184 The relatively higher percentage sorption observed at low initial concentrations of 185 dye may be due to the high ratio of sorptive surface to the dye concentration, which 186 implied that a fewer number of dye molecules were competing for the available binding 187 sites on the adsorbent26. With increasing MB dye initial concentration however, the 188 sorptive surface to dye concentration decreases leading to reduced percent sorption27. 189 190 3.3 Effect of contact time 191 Our adsorption results reveal fast uptake of adsorbate species at the initial stages 192 of contact period. In fact, in all the initial concentrations of MB dye used, over 80% 193 sorption was achieved within the first 5 min. As contact time increases, the adsorption of 194 MB dye in the solution increases rapidly at the beginning with a gradual slow down until 195 it remained at about 120 minutes, which was then taken as the equilibrium time. A plot of 196 percent sorption against time (t) depicts a typical contact time for the sorption of MB dye 197 by RMH (Fig. 3). The initial rapid phase, which indicates a very spontaneous sorption 198 process, may be due to the large number of vacant sites available at the initial period of 199 the sorption28. The increase in quantity adsorbed continued slowly until a quasi-static 200 point is reached at about 120 min. 201 202 203 204 3.4 Adsorption isotherm models 205 and the adsorbate adsorbed on the surface of the adsorbent at equilibrium at constant 206 temperature. The equilibrium adsorption isotherm is very important to design the An adsorption isotherm is the relationship between the adsorbate in the liquid phase 8 207 adsorption systems. For solid-liquid systems, several isotherms are available. The 208 Langmuir isotherm takes an assumption that the adsorption occurs at specific 209 homogeneous sites within the adsorbent and the equation takes the form29, 30: qe 210 q m k a Ce 1 k a Ce (3) 211 where qe is the amount of dye adsorbed per unit mass at equilibrium (mg/g); qm is the 212 maximum possible amount of dye that can be adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent 213 (mg/g); Ce is concentration of sorbate in the solution at equilibrium (mg/L); ka is the 214 sorption equilibrium constant. The linearised form of equation (3) is Ce C 1 e qe k a q m q m 215 216 A plot of (4) Ce 1 versus Ce gives a straight line (Fig. 4), with a slope of and qm qe 1 . The effect of isotherm shape can also be used to predict whether an k a qm 217 intercept 218 adsorption system is “favorable” or “unfavorable.” According to Hall et al.31, the 219 essential features of the Langmuir isotherm can be expressed in terms of a dimensionless 220 constant separation factor or equilibrium parameter KR, which is defined by the following 221 relationship: 222 KR 1 1 K a Co (5) 223 where KR is dimensionless separation factor; Ka is Langmuir constant ( L/mg); Co is the 224 initial concentration of sorbate (mg/L). The separation factor, KR, indicates the nature of 225 the adsorption process as given in Table 1. The Langmuir isotherm model was chosen for 226 the estimation of maximum adsorption capacity corresponding to complete monolayer 9 227 coverage on the RMH. The Langmuir data are given in Table 2. The sorption capacity, 228 qm, which is a measure of the maximum sorption capacity corresponding to complete 229 monolayer coverage showed that RMH adsorbent seemed to have a high monolayer 230 adsorption capacity. The adsorption coefficient, Ka, related to the apparent energy 231 (surface energy) of sorption was found to be 0.991 L/mg. The high magnitude of qm 232 (47.39 mg/g) indicates that the amount of MB dye per unit weight of sorbent (to form a 233 complete monolayer on the surface) seems to be high. A moderate Ka-value implies 234 moderate surface energy in MB dye-RMH system, thus indicating a probable moderate 235 binding between MB dye and sorbent32. The values of KR for initial dye concentrations 236 from 5 to 500 mg/dm3 were found to range from 0.00209 to 0.01680. The KR values 237 indicate that adsorption is more favourable for the Methylene blue/RMH system as they 238 fall between 0 and 1 (Table 1). The Langmuir model shows a strong conformation to 239 experimental data based on satisfactorily values of the obtained linear regression 240 coefficient, R2 and non-linear error analysis (Table 2). 241 242 243 244 245 The Freundlich isotherm is an empirical equation employed to describe the heterogeneous system33. The equation is given below: qe K f Ce 1/ n (6) The linear form of the equation is: log q e log K f 1 log C e n (7 ) 246 where qe is the amount of MB dye adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent (mg/g); Kf (L/g) 247 and n are Freundlich constants which are measures of adsorption capacity and intensity 248 of adsorption respectively34, Ce is the equilibrium concentration in mg/L. 10 249 From the straight line, obtained by plotting log qe against log Ce (Fig. 5), the 250 corresponding slope and intercept can be determined from 1/n and log Kf values. The 251 Freundlich data are given in Table 2, with regression factor, R2, of 0.8732 and sum of 252 error square (SSE) of 11.28. The values of Freundlich parameters n and Kf are 3.211 (i.e. 253 1/n = 0.311) and 12.578 respectively. From the Freundlich equation, the high value of Kf 254 of RMH (12.578) indicates high uptake of MB dye from aqueous solution32. Furthermore, 255 it was observed that the n-value satisfy the condition(s) of heterogeneity35, i.e 1 < n < 10 256 as well as 0 < 1/n < 1. The value of 1/n less than 1 describes a favorable nature of 257 methylene blue adsorption onto RMH, however, the model is not able to describe the 258 experimental data properly because of the poor linear correlation and high SSE values 259 (Table 2). 260 261 262 The Temkin isotherm was studied to explore the energy distribution pattern of the RMH adsorbent. The linear form of the Temkin isotherm model can be expressed as; q a b In Ce (8) 263 where “q” is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per unit weight of adsorbent, “a” is a 264 constant related to adsorption potential of the adsorbent and “b” is a constant related to 265 adsorption intensity. Temkin isotherm contains factors that explicitly take into account 266 the interactions between adsorbing species and the adsorbate. 267 The Temkin isotherm parameters generated from the Temkin isotherm plot (Fig. 6) 268 are given Table 2. Its correlation coefficient, R2 of 0.983 is also high, which is an 269 indication that the more energetic adsorption sites are occupied first by molecules of MB 270 dye, and that the adsorption process is likely to be chemisorption [36]. The Temkin 11 271 model shows a strong conformation to experimental data based on satisfactorily values of 272 the obtained linear regression coefficient, R2 and non-linear error analysis (Table 2). 273 274 3.5 Kinetic study 275 The modeling of the kinetics of adsorption of MB dye by RMH was investigated 276 by four common models, namely the Largergren pseudo-first order37, Ho’s pseudo- 277 second order17, 38, 39, Elovich model40 and Morris – Weber41 equations. 278 The pseudo-first order model was described by Largergren as; log (qe qt ) log qe 279 k1t 2.303 (9) 280 The qe (mg g–1) is the amount of dye adsorbed at equilibrium, qt (mg g–1) is the amount 281 of dye adsorbed at time t and k1 is the pseudo first-order rate constant. A plot of log (qe 282 – qt) versus agitation time gives a straight line (Fig. 7), with coefficient of correlation, R2, 283 for the five different initial concentrations of MB dye investigated ranging from 0.8 – 284 0.9816. The values of pseudo-first order rate constant, k1, computed from the slope of the 285 linear plot, ranged from 1.41 x 10–2 – 4.08 x 10–2 min-1 (Table 3). The experimental qe 286 values did not agree with the calculated values based on the high values of its SSE. This 287 therefore shows that the adsorption of MB dye onto RMH does not follow a pseudo- first 288 order kinetics. 289 The pseudo-second order model42 is expressed as 290 t 1 t qt h q e (10) 291 h k 2 qe (11) 2 12 292 where qe is the amount of the solute adsorbed at equilibrium per unit mass of adsorbent 293 (mg g–1) , qt is the amount of solute adsorbed (mg g–1) at any given time t (min) and k2 is 294 the rate constant for pseudo-second-order adsorption (g mg–1 mm–1) and h, known as the 295 initial sorption rate. 296 If the sorption follows pseudo-second order, h, is described as the initial rate 297 constant as t approaches zero. From the plot (Fig. 8), values of k2, R2 and qe were 298 calculated (Table 3). The correlation coefficients obtained for the pseudo-second-order 299 kinetic model are very high; and are close or equal to unity (0.999 – 1) for the initial MB 300 dye concentrations studied. There is also a very good agreement between the 301 experimentally obtained and calculated values of qe based on the low values of its SSE 302 (Table 3). This shows that the mechanism of the adsorption of MB dye by RMH can best 303 be described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, based on the assumption that the 304 rate limiting step may be chemisorption involving valence forces through sharing or 305 exchange of electrons between the hydrophilic edge sites of the RMH and MB dye ions 306 38, 43 307 increase in sorption capacity from 1.23 to 24.51 mg/g; which is also in agreement with 308 observations of others44, 45. 309 . Increasing the initial concentration of MB dye from 5 to 100 mg/L causes an The Elovich model is expressed as46, 47; qt 1 In ( ) 1 In t (12) 310 where is the initial adsorption rate (mg g 1 min 1 ), is the desorption cons tan t ( g mg 1 ) and qt is the amount of solute adsorbed (mg g 1 ) at any given time, t (min .) 13 311 A plot of qt versus In t gives a straight line with intercept 312 (Fig. 9). 1 In ( ) and slope, 1 313 Table 3 shows the kinetic data of Elovich model for the adsorption of MB dye on 314 RMH. The initial adsorption rate, α; desorption constant, β; and the correlation 315 coefficients, calculated from the plot for the different initial concentrations of MB dye are 316 given in Table 3. The correlation coefficients obtained from the Elovich kinetic model are 317 also high; ranging from 0.8714 to 0.9591. Thus, Elovich equation could also be a good 318 model for the adsorption process48. 319 The relationship between the initial concentrations of MB dye, Co, and the Elovich 320 initial adsorption rate, α, was also investigated. As shown in the table (Table 3), the 321 values of α increase with increasing Co, until a maximum is reached, after which a further 322 increase in Co resulted in a decrease in α. For instance, α rose from 4.5 x 1066 to 3.6 x 323 10111 mg g– 1 min– 1 with an increase in Co from 5 mg/L to 25 mg/L (Table 3). Further 324 increase in Co from 25 mg/L through 50 mg/L to 100 mg/L recorded a drastic fall in α 325 from 3.6 x 10111 to 1.6 x 109 mg g– 326 observed between Co and the Elovich model desorption constant, β. For instance, an 327 increase in Co from 5 mg/L to 25 mg/L led to a decrease in β from 133.333 to 42.918 g 328 mg–1 (Table 3). 329 330 331 1 min–1. However, an inverse relationship was The kinetics of sorption of MB dye was also investigated using Morris-Weber equation41 in the following form: qt K id t (13) 14 332 where qt is the sorbed concentration at time “t”, and “Kid” is the rate constant of 333 intraparticle transport. According to Morris and Weber41, a plot of sorption capacity at a 334 given time, qt, versus √t should be a straight line if intraparticle diffusion is involved; and 335 if it is the only rate-determining factor, the line passes through the origin. However, if the 336 plot has an intercept (i.e. does not pass through the origin), it shows that intra-particle 337 diffusion may not be the only factor limiting the rate of the sorption process49. A 338 modified form of Morris-Weber equation that takes care of boundary layer resistance was 339 therefore proposed as48, 50, 51: 340 341 342 qt K id t X i (14) where Xi depicts the boundary layer thickness [51]. 1 343 The qt was plotted against, t 2 for the sorption of MB on RMH for different initial 344 dye concentrations (Fig. 10). The correlation coefficients obtained from the plots were 345 not high (0.6612 – 0.9689) and the straight lines do not pass through the origin (the 346 intercepts > 0). The deviation of these lines from the origin indicates that intra-particle 347 diffusion may be a factor in the sorption process, but not the only controlling step52. The 348 values of Kid computed from the slopes of the plot ranged from 0.003 – 0.3398 mg g-1 349 min-1/2. The larger the intercept, the greater is the contribution of the surface sorption 350 (boundary layer resistance) in the rate–limiting step53. Both Kid and Xi have direct 351 relationship with the initial concentration of MB dye (Table 3). Evidently from our 352 results, the higher the initial concentration, the greater is the effect of boundary layer and 353 its contribution on the rate determining step. 354 15 355 3.6 Error Analysis 356 Ho15 reported that it is better to use the non-linear analysis method for analyzing 357 the experimental data instead of linear regression analysis alone to compare the best- 358 fitting isotherms. When using the non-linear method, there was no problem with 359 transformations of non-linear isotherms to linear forms. In this study, a non-linear 360 analysis was used to compare the best-fitting isotherms using sum-of-error square. 361 Analysis of nonlinear error function (SSE test), revealed that both Langmuir and 362 Temkin models are applicable since the resulting errors were very small (Table 2). These 363 findings are very important to indicate that RMH might have homogenous and 364 heterogeneous surface energy distributions. However, the Freundlich model is not able to 365 describe the experimental data properly because of the poor linear correlation and high 366 SSE values (Table 2). The SSE value more than 5% is not recommended due to 367 intolerant margin of deviation between the experimental data and the model calculated 368 data. 369 Further verification of the applicability of the kinetic models was also tested with 370 the sum of error squares (SSE) and linear regression. The higher the value of R2 and the 371 lower the value of SSE, the better is the goodness of fit and therefore the applicability of 372 the kinetic model. Values of SSE calculated from pseudo-second order equation were 373 very low at all the concentration range considered, when compared with those of others 374 (Table 3), which further confirms the validity of the applicability of the pseudo-second 375 order kinetic model to the present sorption process over the other kinetic models 376 investigated in this study. 377 378 16 379 CONCLUSION 380 Raw melon husk (RMH) is able to adsorb Methylene Blue dye from aqueous solutions. 381 Optimum sorption of MB dye by RMH is achieved at an adsorbent dosage of 0.200 g/L 382 of solution for an equilibrium time of 120 minutes. It is successful to use the coefficient 383 of determination of the non-linear method for comparing the best fit of the Langmuir, 384 Freundlich, and Temkin isotherms. The Temkin and the Langmuir isotherms had higher 385 coefficients of determination than that of Freundlich isotherm but Langmuir might be the 386 best-fitting isotherm. The kinetic data can best be described by the pseudo second order 387 kinetic model. Apparently, it can be concluded that the most applicable isotherm to 388 describe methylene blue dye–RMH adsorption system are Langmuir and Temkin 389 isotherms. Their values of regression coefficients, R2 and the non-linear error function 390 (SSE) are satisfactory. The Freundlih isotherm is the least applicable isotherm as the 391 linear regression coefficients, R2 were less than 0.9 and the sum of error square (SSE) is 392 more than 5%. 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 REFERENCES [1] Robinson, T., Mc Mullan, G., Marchant, R., Nigam, P. (2001). Remediation of dyes in textile effluent, a critical review on current treatment technologies with a proposed alternative. Bioresour. Technol., 77, 247 – 255. [2] Babel, S. and Kurniawan, T.A. (2003). Low-cost adsorbents for heavy metals uptake from contaminated water: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 97, 219-243. [3] Ponnusami, V., Vikram, S. and Srivastava, S.N. (2008). Guava (Psidium guaiava) leaf powder: Novel adsorbent for removal of Methylene blue from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 152, 276-286. [4] Özer, A. and Dursun, G. (2007). Removal of Methylene blue from aqueous solution by dehydrated wheat bran carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 146, 262-269. [5] Al-Qodah, Z., Lafi, W.K., Al-Anber, Z., Al-Shannag, M. and Harahsheh, A. (2007). Adsorption of Methylene blue by acid and heat treated diatomaceous silica. Desalination. 217, 212- 224. [6] Bulut, Y. and Aydin, H. (2006). A kinetics and thermodynamics study of Methylene blue adsorption on wheat shells. Desalination. 194, 259-267. 17 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 [7] Ghosh, D. and Bhattacharyya, K.G. (2002) Adsorption of Methylene blue on kaolinite. Appl. Clay. Sci. 20, 295-300. [8] Zhu, Y.N., Wang, D.Q., Zhang, X.H. and Qin, H.D. (2009). Adsorption removal of Methylene blue from aqueous solution by using bamboo charcoal. Fresen. Environ. Bull. 18, 369-376. [9] Zafar, S.I., Bisma, M., Saeed, A. and Iqbal, M. (2008). FTIR spectrophotometry, kinetics and adsorption isotherms modelling, and SEM-EDX analysis for describing mechanism of biosorption of the cationic basic dye Methylene blue by a new biosorbent (Sawdust of Silver Fir; Abies Pindrow). Fresen. Environ. Bull. 17, 2109-2121. [10] Aci, F., Nebioglu, M., Arslan, M., Imamoglu, M., Zengin, M. and Kucukislamoglu, M. (2008). Preparation of activated carbon from sugar beet molasses and adsorption of Methylene blue. Fresen. Environ. Bull. 17, 997-1001. [11] Reid R. (1996). Go green - A sound business decision. 1, Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists; 112:103-105. [12] Tor, A. and Cengeloglu, Y. (2006) Removal of Congo red from aqueous solution by adsorption onto acid activated red mud, J. Hazard. Mater.;138:409-415. [13] Senthilkumaar, S., Varadarajan, PR., Porkodi, K., Subbhuraam, C.V. (2005). Adsorption of Methylene blue onto jute fiber carbon: Kinetics and equilibrium studies, J. Colloid Interface Sci.;284:78-82. [14] Ratkowsky, D.A. (1990). Handbook of Nonlinear Regression Models. New York: Marcel Dekker. [15] Ho, Y.S. (2004). Selection of optimum sorption isotherm. Carbon. 42, 2115-2116. [16] Richter, E., Schutz, W. and Myers, A.L. (1989). Effect of adsorption equation on prediction of multicomponent adsorption equilibria by the ideal adsorbed solution theorys. Chem. Eng. Sci. 44, 1609-1616. [17] Ho, Y.S. (2004). Citation review of Lagergren kinetic rate equation on adsorption reactions. Scientometrics, 59 (1), 171-177. [18] Ho, Y.S. (2006). Isotherms for the sorption of lead onto peat: Comparison of linear and non-linear methods. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 15, 81-86. [19] Gunay, A. (2007). Application of nonlinear regression analysis for ammonium exchange by natural (Bigadic) clinoptilolite. J. Hazard. Mater. 148(3): 708-713. [20] Arslanoglu, F. N., Kar, F. and Arslan, N. (2005). Adsorption of dark coloured compounds from peach pulp by using granular activated carbon. Journal of Food Engineering, 68(4): 409-417. [21] Tseng, R.-L., F.-C. Wu and R.S. Juang, (2003). Liquid-phase adsorption of dyes and phenols using pinewood-based activated carbons. Carbon, 41(3): 487-495. [22] Azhar, S.S; Liew, G.A; Suhardy, D; Hafiz, F.K; Irfan H.M.D (2005). Dye removal from aqueous solution by using adsorption on treated sugarcane bagasse. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2(11), 1499-1503. [23] Esmaili, A; Ghasemi, S; Rustaiyan, A (2008): Evaluation of the activated carbon prepared of algae gracilaria for the biosorption of Cu(II) from aqueous solution. American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Env. Sci. 3(6), 810-813 [24] Haris, M.R.H., Sathasvam, K. (2009). The removal of methyl red from aqueous solution using banana pseudostem fibers. Am. J. Appl. Sci., 6(9), 1690–1700. [25] Daniela, S. and Doina, B. (2005). Equilibrium and kinetic study of reactive dye 18 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 brilliant red He-3b adsorption by activated charcoal Acta. Chim. Stov. 52, 73-79. [26] Gupta, R. and Mohapatra, H. (2003). Microial biomass: An economical alternative for removal of heavy metals from waste water. Indian J. Expt. Biol., 41, 945 – 966. [27] Bansat, M., Singh, D., Garg, V.K and Rose, P. (2009). Use of agricultural waste for the removal of nickel ions from aqueous solution: equilibrium and kinetic studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. and Engr., 1(2), 108 – 114. [28] Wong, S.Y., Tan, Y.P., Abdullah, A.H., Ong, S.T. (2009). The removal of basic and reactive dyes using quartenised sugar cane bagasse. J. Phy. Sci., 20 (1), 59– 74. [29] Langmuir, I. (1918). The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum, Journal of American Chemical Society; 40:1361-1403. [30] Ho, Y.S., Huang, C.T. and Huang, H.W. (2002). Equilibrium sorption isotherm for metal ions on tree fern, Process Biochem., 37:1421-1430. [31] Hall, K.R., Eagleton, L.C., Acrivos, A., Vermeulen, T. (1966). Pore- and soliddiffuion kinetics in fixed-bed adsorption under constant-pattern conditions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fund.; 5:212-223. [32] Aksu, Z and Yener, J. (2001). A comparative adsorption/biosorption study of monochlorinated phenols onto various sorbents. Waste Manage., 21, 695 – 702. [33] Freundlich, H.M.F. (1906). Über die adsorption in lösungen, Z. Phys. Chem. 57A, 385–470. [34] Malik, P.K (2004): Dye removal from wastewater using activated carbon developed from sawdust: Adsorption equilibrium and kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 113, 81–88. [35] Khalid, N., Ahmad, S., Toheed, A. (2000). Potential of rice husk for antimony removal., Appl. Radiat. Isot., 52, 30 – 38. [36] Lain-Chuen, J., Cheng-Cai, W., Chung-Kung, L., Ting-Chu, H. (2007). Dyes Adsorption onto organoclay and MCM-41. J. Env. Eng. Manage. 17(1), 29-38 [37] Lagergren, S. (1898). Zur theorie der sogenannten adsorption gelöster stoffe. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens. Handlingar, Band 24(4), 1-39. [38] Ho, Y.S. (2006). Review of second-order models for adsorption systems. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 136 (3), 681-689. [39] Ho, Y.S. and McKay, G. (1998). Sorption of dye from aqueous solution by peat. Chemical Engineering Journal, 70 (2), 115-124. [40] Zeldowitsch, J. (1934). Über den mechanismus der katalytischen oxydation von CO an MnO2. Acta Physicochimica URSS, 1 (3-4), 449-464. [41] Weber, Jr., W.J. and Morris, J.C. (1963). Kinetics of adsorption on carbon from solution. Journal of the Sanitary Engineering Division-ASCE, 89, 31-59. [42] Ho, Y.S (1995): Adsorption of heavy metals from waste streams by peat. Ph.D thesis, The University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK. [43] Gucek, A., Sener, S., Bilgen, S., Mazmanci, A. (2005). Adsorption and kinetic studies of cationic and anionic dyes on pyrophyllite from aqueous solutions. J. Colloid Interf. Sci., 286, 53-60. [44] Oladoja, N.A., Asia, I.O., Aboluwoye, C.O., Oladimeji, B., Ashogbon, A.O. (2008). Studies on the sorption of basic dye by rubber (herea brasiliensis) seed shell. Turkish J. Eng. Env. Sci. 32, 143-152. [45] Malarvizhi, R., Sulochana, N. (2008). Sorption isotherm and prepared from wood apple shell. J. Env. Prot. Sci. 2, 40-46 19 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 [46] Sparks, D.L. (1986). Kinetics of reactions in pure and mixed systems in soil physical chemistry. CRC Press, Florida, 21 – 25. [47] Okiemen, F.E. and Onyega, V.U. (1989). Binding of cadmium, copper, lead and nickel ions with melon (Citrullus vulgaris) seed husk. Biological waste, 29, 11 –16. [48] Igwe, J.C. and Abia, A.A. (2007). Adsorption kinetics and intraparticulate diffusivities for bioremediation of Co(II), Fe(II) and Cu(II) ions from wastewater using modified and unmodified maize cob. Int. J. Phy. Sci., 2(5), 119 – 127. [49] Ho, Y.S., Mckay, G. (2003). Sorption of dyes and copper ions onto biosorbents. Proc. Biochem., 38, 1047 – 1061 [50] Mckay, G., Poots, J.P. (1980). Kinetics and diffusion processes in colour removal from effluent using wood as adsorbent. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol., 30, 279 – 292. [51] Abia, A.A; Didi, O.B; Asuquo, E.D. (2006). Modeling of Cd2+ sorption kinetics from aqueous solutions onto some thiolated Agricultural waste adsorbents. J. Appl. Sci. 6(12), 2549-2556. [52] Onge, S.A., Seng, C.E., Lom, V.(2007). Kinetic of adsorption of Cu(II) and Cd(II) from aqueous solution on rice husk and modified rice husk, Elect. J. Env. Agric. and Food Chem., 6(2), 1764 – 1774. [53] Arvoli, S. and Thenkuzhali, M. (2008). Kinetics, mechanistics, thermodynamics and equilibrium studies on the adsorption of rhodamine B by acid activated low cost carbon. E- Journal of Chemistry, 5(2), 187 – 200. 20 549 550 551 Table 1: The process nature of separation factor KR KR > 1 KR = 1 0<K<1 KR = 0 552 553 554 555 556 557 558 Type of process Unfavorable Linear Favorable Irreversible Table 2: Isotherm model parameters for adsorption of MB dye onto RMH Freundlich R2 0.873 SSE(%) kf 11.28 12.578 Langmuir 1/n 0.3114 R2, 0.999 SSE(%) 3.71 559 560 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 21 qmax 47.39 Temkin ka 0.991 R2 0.983 SSE(%) a 2.46 23.17 b 4.72 585 586 587 588 589 590 Table 3: Comparison of rate constants and other parameters for various kinetic models at different initial concentrations Parameters qe (expt.) Pseudo-first order R2 k1 qe (cal.) SSE(%) Pseudo –second order R2 k2 qe (cal.) h SSE(%) Elovich model R2 α β SSE(%) Morris-Weber R2 Kid Xi SSE(%) C0 (mg/L) 5 1.232 10 2.468 25 6.192 50 12.426 100 24.347 0.864 0.016 0.037 103.2 0.910 0.024 0.031 129.7 0.800 0.014 0.070 125.5 0.741 0.017 0.632 508.9 0.982 0.041 3.725 427.3 1.000 2.106 1.231 3.19 0.1 1.000 3.358 2.468 20.4 0.1 1.000 1.306 6.188 50.0 0.4 1.000 0.165 12.407 25.3 1.6 0.999 0.037 24.509 22.4 1.2 0.861 4.5x1066 133.33 0.68 0.817 3.2x10107 104.17 0.15 0.893 3.6x10111 42.92 0.22 0.923 1.4x1019 4.05 4.69 0.959 1.6x109 1.07 27.66 0.9689 0.003 1.193 0.23 0.6612 0.0033 2.432 0.45 0.7394 0.0081 6.078 1.47 0.7363 0.0844 11.515 12.32 0.8619 0.3398 20.867 68.15 591 592 593 594 595 596 597 598 599 600 601 602 603 604 605 22 50 102 45 100 40 qe (mg/g) 30 96 25 94 20 qe % MB Sorption 15 % MB Sorption 98 35 92 10 90 5 0 88 0 606 607 608 609 0.2 0.4 RMH dosage (g) 0.6 0.8 Fig. 1: Effect of adsorbent dosage on MB dye removal 50 120 45 qe (mg/g) 35 80 30 qe % MB sorption 25 60 20 40 15 10 % MB sorption 100 40 20 5 0 0 610 611 612 613 100 200 300 400 500 Initial concentration of MB (mg/L) 0 600 Fig. 2: Effect of MB dye concentration on sorption by RMH 14 120 12 100 qt (mg/g) 80 8 60 6 qt %MB Sorption 4 20 2 0 0 614 615 616 617 40 % Mb Sorption 10 50 100 150 0 200 t (min) Fig. 3: Effect of contact time on sorption of MB onto RMH 23 7 6 5 Ce/qe 4 3 2 1 0 0 618 619 620 621 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 Ce (mg/L) Fig. 4: Langmuir sorption isotherm of MB onto RMH 2 1.8 1.6 1.4 log qe 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -3 622 623 624 625 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 log Ce Fig. 5: Freundlich sorption isotherm of MB dye onto RMH 24 60 50 40 qe 30 20 10 0 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 -10 ln Ce 626 627 628 629 Fig. 6: Temkin sorption isotherm of MB dye onto RMH 1 0.5 0 log (qe-qt) 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 -0.5 5mg/l 10mg/l 25mg/l 50mg/l 100mg/l -1 -1.5 -2 -2.5 -3 630 631 632 633 t (min) Fig. 7: Pseudo first-order kinetic plot for the sorption of MB onto RMH 25 140 120 100 5mg/l 10mg/l t/qt 80 25mg/l 50mg/l 100mg/l 60 40 20 0 0 50 100 150 200 t (min) 634 635 636 Fig. 8: Pseudo -second order kinetic plot for the sorption of MB onto RMH 30 25 5mg/l qt (mg/g) 20 10mg/l 25mg/l 50mg/l 15 100mg/l 10 5 0 0 637 638 639 640 1 2 3 4 5 6 ln t Fig. 9: Elovich plot for the sorption of MB onto RMH 26 30 25 qt 20 5mg/l 10mg/l 25mg/l 50mg/l 100mg/l 15 10 5 0 0 641 642 643 644 645 2 4 6 8 t 10 12 14 1/2 Fig. 10: Morris-Weber equation for the sorption of MB onto RMH 27