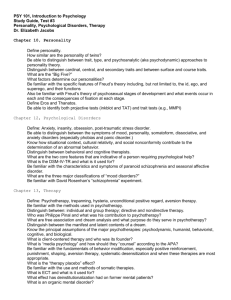

Contents - FatAids.org

advertisement