New York Public Library

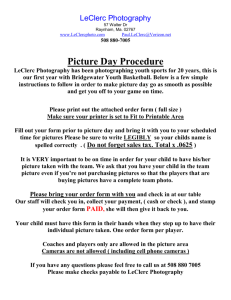

advertisement