No question: lexicalization and grammaticalization

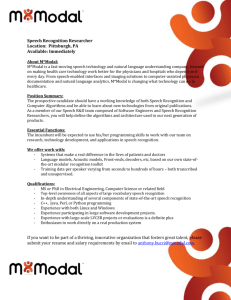

advertisement

First and corresponding author: Kristin Davidse Second author: Simon De Wolf Address: University of Leuven, Linguistics Department, Blijde-Inkomststraat 21, B3000 Leuven, Belgium Tel. +32 [0]16 32 48 11 Fax: +32 [0]16 32 47 67 Email corresponding author: kristin.davidse@arts.kuleuven.be Home phone corresponding author: +32 [0]16 62 29 25 Full title of article: Lexicalization and grammaticalization: the development of idioms and grammaticalized expressions with no question Short title of the article (for running head): Lexicalization and grammaticalization: (there’s) no question Word count (all inclusive): 7,996 Character count (with spaces): 52,760 Lexicalization and grammaticalization: the development of idioms and grammaticalized expressions with no question1 1. Introduction In Present-day English, the string no question is used mainly to modally qualify a proposition, i.e. with grammatical meaning, either as adverbial (1) or as part of a clause (2)-(3). As pointed out by Kjellmer (1998), there are two modal clausal structures, expressing opposite polarity values. There’s no question followed by a finite clause is always positive, as in (2), which can be paraphrased as ‘he definitely must stay’. There’s no question of + gerund conveys negative polarity, as in (3), which means ‘Her Majesty will NOT turn up unannounced on your doorstep’. (1) You have to be mentally strong but too many of our players jacked it in. There will be changes on Saturday, no question.” (WB)2 (2) He's better than our two former managers ... The best clubs have continuity at the top. There is no question he must stay. (WB) (3) There’s no question of Her Majesty turning up on your doorstep unannounced. (WB) Less commonly, no question is also used lexically, as in the semi-fixed idioms illustrated in (4) and (5). We identified two idioms with the form there be no/never any/etc. question. In (4), the expression means ‘not be challenged’ (OED VIII: 48), while in (5) it means ‘not be an issue’ (with question used in the sense of ‘subject of discussion’, OED VIII: 48). (4) ... for Tolkien, Rickettsia quintana proved a life-saver. The army was notoriously suspicious about any attempt to `cry off sick', but there was no question about Tolkien 's condition. (WB) (5) We also wanted to know if he wanted anything out of it, and because there was no question of payment, ..., we felt reassured that he really was doing it for us. (WB) The synchronic presence of idiomatic and grammatical layers suggests that processes of both lexicalization and grammaticalization took place. This article sets out to reconstruct these processes on the basis of diachronic and synchronic data described in Section 2. Lehmann (2002) has proposed that lexicalization often precedes the grammaticalization of periphrastic expressions. As we will show, the development of the clausal structures with (no) question is a case in point. We will reconstruct the formation of the two idioms, ‘be (un)challengeable’ and ‘be (not) at issue’, and we will examine how they relate diachronically to the two grammaticalized modal patterns, the positive and the negative one (Section 3). This requires us to spell out the recognition criteria of lexicalized versus grammaticalized uses in the concrete analysis of our data (Sections 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4). In these sections, we will focus mainly on criterial syntagmatic features, taking a functional-structural approach as developed in Langacker (1999), Halliday (1994), Hopper & Traugott (2003) and Boye & Harder (2007). The history of the clausal patterns with (no) question also forms the occasion for us to contribute a more personal position to the current theoretical debate about the difference between lexicalization and grammaticalization. Taking our inspiration from the (neo-)Firthian tradition (Firth 1951/1957), we will propose that lexicalization and grammaticalization lead to different types of paradigmatic organization. A lexicalized item imposes lexicosemantically motivated collocational and colligational relations, while grammaticalizing elements come to express meaning options, with their typical interdependencies, from grammatical systems (Section 3.5). We will also study the origin and development of modal adverbial no question. Simon-Vandenbergen’s (2007: 32) study of there is no doubt and no doubt found that the chronology in which these expressions emerged is compatible with the hypothesis that the adverbial developed by ellipsis from the clausal structures. As ellipsis could also be considered the possible origin of no question, we will investigate whether this adverbial resulted via ellipsis from the clausal structures (Section 4). Conclusions will be formulated in Section 5. 2. Data The noun question occurs from c.1300 in English, which made it necessary to collect diachronic data from Middle English on. We used the Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Middle English (PPCME), the Penn-Helsinki Parsed Corpus of Early Modern English (PPCEME), and the Corpus of Late Modern English Texts (CLMETEV). As we wanted to trace how the strong association of question with negative quantifier came about, we included all nominal hits, manifesting all the early variation in the expressions with question. In total, this diachronic dataset contained 5,289 tokens. The synchronic dataset was compiled from WordbanksOnline corpus. For reasons of comparability with the diachronic data, we extracted data from written British English sources only. As our focus in Present-day English was on the uses of the highly entrenched expressions with no question, we took a random sample of 250 hits, obtained by the search string no question. 3. The lexicalization and grammaticalization of clauses with no question 3.1. Middle English (1150-1500) The earliest examples in which question is followed by a complement are from Middle English, occurring between 1350 and 1420. They are all instances of a now obsolete composite predicate make + question. which meant ‘put a question’, ‘ask’ (OED XIII: 47). The different determiners that could precede question, a, Ø, this, show that this was a semi-fixed idiom. It started out taking prepositional phrase complements, e.g. (6), but, from 1420 on, the predicate is also attested with clausal complements, as in (7). (6) And Joon was not git sent in to prisoun. Therfor a questioun was maad of Jonys disciples with the Jewis, of the purificatioun. (PPCME, 1350-1420) (7) And tei tat were gadered to go with him, if tei mad question to what entent tei schuld rise, ... (PPCME, 1420-1500) We view the formation of this composite predicate as lexicalization in the sense of the conventionalized association of a specific sense with a combination of words at the level of the lexicon (Blank 2001: 1603). Make a/Ø question behaves as a lexical item in that its meaning ‘ask’ constrains the complements it can take: either of / about + NP (6) or indirectly reported question (7). It is also ‘addressable’ as the main point of the utterance, e.g. was a question really made of the purification? (6). This is, as argued by Boye & Harder (2007: 581-585), characteristic of the lexical use of complement-taking predicates and correlates with its primary information status in discourse usage. 3.2. Early Modern English (1500-1710) In Early Modern English, the composite predicate make a/Ø question developed another meaning. Example (8) can still be interpreted as the President asking questions about the Earl of Ormond’s Liberties, but also, in the light of the contextual clue bringe the Liberties into dispute, as ‘calling the Erle’s liberties into question’. In other words, (8) is a bridging context in which we see make question develop the meaning of ‘challenge’. (8) But the President tooke it in ill Part, and wrote a sharpe Letter … unto the Erle’s Officers ... wherein he did sharpely reprend them, ... that being learned and wise, would bringe the Liberties into dispute, by making of undue Excuses. He did assure them that he had not byn yet of Mynd to make any Question of the Erle of Ormonds Liberties; (PPCEME, 1570-1640) Also in the Early Modern English period, between 1500 and 1570, the first existential examples occur. They contain different verbs besides be, e.g. arise in (9) and be proponed in (10), but all describe that ‘a question was asked’. These existential expressions have the same two complementation types as make Ø/a question in its ‘ask’ sense: either a prepositional phrase, as in (9), or a reported question, as in (10). (9) And ther arose a question bitwene Iohns disciplines and the Iewes a bout purifiynge. (PPCEME, 1500-1570) (10) After this were there certaine questions among his councell proponed, whether the king needed in case to have any scruple at all, and if he had, what way were best to be taken to deliver him of it. (PPCEME, 1500-1570) We view these semi-fixed phrases as lexicalizations for the same reasons as adduced for make Ø/a question in section 3.1, i.e. their sanctioning of specific complements and their primary discourse status. As was the case with make Ø/a question, the existential expressions also shifted to a different meaning, illustrated in (11), where there hath ben question of his safty means ‘his safety had been at stake’. In examples like (11) we see the emergence of there be question as a semi-fixed idiom meaning ‘be at issue’, which has persisted into Present-day English. (11) considering how many of ours, wee haue sacrificed for his sake, and how little wee haue weighed Vtility, when there hath ben question of his safty. (PPCEME, 1570-1640) 4.3. Late Modern English (1710-1920) It is in the Late Modern English period that the clausal structures with question begin to occur with some frequency. Table 1 gives the occurrences and relative frequencies of the three structure types for the three historical periods. It shows that the Late Modern English data turned up 139 tokens as opposed to 7 in Early Modern English. Structure type Existential Copular Make question Adverb TOTAL Middle English n % 0 0% 0 0% 5 100% 0 0% 5 Early Modern English n % 4 40% 0 0% 3 30% 3 30% 10 Late Modern English n % 73 51.8% 44 31.2% 22 15.6% 2 1.4 141 Table 1: Absolute and relative frequencies of structure types across time periods The make question pattern started off the whole development, but by Late Modern English it had become the least common and the existential structures had become the most frequent, while copular structures like it is no question were the second most common pattern. There are not only quantitative changes, the network of structures and meanings associated with question is also amplified and diversified. Importantly, the two idiomatic patterns, meaning ‘challenge’ and ‘be at issue’, both specialize towards negative contexts with no question. It is then that they start on the road to grammaticalization, one towards positive modal meaning and the other towards negative modal meaning. The lexicalization processes not only precede and enable grammaticalization by pre-forming the periphrastic grammaticalizing expressions, but, as we will show, they also semantically determine the specific resulting modal meanings. 3.3.1. From ‘be unchallengeable’ to positive modal marker The meaning of ‘challenge’ expressed previously by make Ø/a question is now also found in existential examples, e.g. (12). The idiom specializes for negative contexts, and tends to be accompanied by intensifying elements, e.g. not the least in (12), yielding the meaning ‘not be challengeable at all’. (12) There is not the least question of its being original: one might as well doubt the originality of King Patapan! (CLMETEV, 1710-1780) In (12), there is not the least question of its being original is addressable as the utterance’s main claim (‘can one really not challenge its originality?’), which is reformulated and re-asserted by the following clause one might as well doubt the originality. There is not the least question in (12) is thus a primary lexical use, attesting to a second lexicalization process in which the form there be no question came to be conventionally associated with the meaning ‘be not challengeable’. This new idiom is always followed by a complement clause. Importantly, this complementation construction is fundamentally different from the earlier one meaning ‘ask’ illustrated in (10). In (10) we have an instance of reported speech, consisting of a represented speech situation, were there certaine questions proponed, and indirectly reported questions. By contrast, (12) is a factive construction: its being original is a complement that is presupposed true (Kiparsky & Kiparsky 1971) and the matrix there is not the least question of explicitly evaluates and emphasizes the truth of this complement. With the shift from reported speech to factive construction, the nature of the complement changes from question to statement. Non-finite its being original is functionally a statement: there is not the least question that ‘it is original’. It is this idiom with negative sense ‘be unchallengeable’ that grammaticalizes into a positive emphatic modal marker, as illustrated in (13). (13) there is no question but the regard to general good is much enforced by the respect to particular. … where the greatest public wrong is also conjoined with a considerable private one, no wonder the highest disapprobation attends so iniquitous a behaviour. (CLMETEV, 1710-1780) Example (13) shows a reversal of the discursive nucleus-margin relation (Hopper & Traugott 2003: 207-9). The primary point of the utterance is the regard to general good is much enforced by respect for the particular, as shown by its addressability by a really-query (is it really enforced?) and tag (is it?) (Boye & Harder 2007). The structural matrix there is no question has become secondary in the discourse in that it functions, as is typical of a grammatical element, as an operator or modifier of the proposition. In contrast with examples (7) and (10), it is not addressable as the main point of the utterance. It expresses he speaker’s modal comment, paraphraseable as ‘definitely’, on the content of what s/he is saying. This goes together with scope expansion: whereas lexical uses of there be no question have a scopal relation to their phrasal (7) or clausal complement (12) only, there is no question in (13) functions on a global utterance level (Brinton 2008: 131). Its modal reading is contextually supported by the following adverbial, no wonder, which modifies the statement strongly condemning a public wrong because it is also a private wrong, i.e. a reformulation of the proposition emphasized by there’s no question. The same evolution towards modal marker takes hold of the other idiomatic clausal structures meaning ‘be unchallengeable’. This development is illustrated in (14) for the pattern with make (a/no) question. (14) Till I cried out: “You prove yourself so able, Pity! You was not Druggerman at Babel; For had they found a linguist half so good I make no question but the tower had stood.” (CLMETEV, 1710-1780) There is discursive reversal of the nucleus-margin relation, as shown by the fact that the conditional clause in (14), for had they found a linguist half so good, clearly relates to the complement rather than the matrix. I make no question but functions as emphatic positive modal marker of the claim the tower had stood. Like a number of emerging existential modal markers of that period, including (13) above, it has complementizer but, a use sanctioned by the negation in the structural matrix (OED I: 1212). The no question but (that) pattern adds an emphatic meaning element. The grammaticalization of the copular idiomatic pattern expressing ‘nonchallengeability’ progresses more slowly. For instance, in (15) it can be no question, which echoes the primary assertion may be reasonably supposed, is still more propositional than the other matrices in (13) and (14). The copular matrices continue to take indirect questions, but some of these can be interpreted as rhetorical statements. In (15), the indirect questions express the possible alternatives, but the context signals that surely the only option is that ‘it be pressed forward’. (15) It may, therefore, be reasonably supposed that the propriety of a law to prevent the exportation of victuals is admitted, and surely it can be no question, whether it ought to be pressed forward, or to be delayed till it will be of no effect. (CLMETEV, 1710-1780) The pragmatic meaning of (15) is thus emphasis of a desired path of action, conveyed by the deontic modal ought to. What is marked here as incontrovertible is not a truth claim, but an obligation, i.e. a deontic statement. Once the positive modal use of the clausal structures with no question was in place, it extended quickly from qualifying truth-claims to qualifying desired actions. From 1850 on, there be no question, is found with deontic statements, e.g. (16). (16) At present the receiving apparatus is fixed on only some 650 steamers of the merchant marine ... . There is no question that it should be installed, along with wireless apparatus, on every ship of over 1000 tons gross tonnage. (CLMETEV, 1850-1920) Summing up, the change from lexical matrix clause to positive modal marker coincides with the extension of the ‘challenge’-idiom to other clausal structures (than with make) and to negative contexts. After all, in the negative sense of ‘being unquestionable’ for which it is specialized since Late Modern English, the lexicalized clauses are very close to the meaning of the grammaticalized comment clauses (‘definitely’). It is plausible, then, to assume that the negative idioms’ polarity determined the polarity of the modal comment clauses as emphatically positive. 3.3.2. From ‘not be at issue’ to negative modal marker The second idiomatized pattern, there be (no) question of in the sense of ‘be at issue’, specializes for negative contexts and increases in frequency some 150 years later than the ‘challenge’-idioms, between 1850 and 1920. Before, it was exclusively followed by prepositional phrases, e.g. (17), but from 1850 on, the expression can take clausal complements, in the form of non-finite clauses, e.g. (18) and (19). Some of these are liable to modal inferences. In (18), for instance, inviting him was never raised as an issue, as contextually supported by The latter never spoke of. At the same time, the fact that inviting him was never spoken of invites the inference that there was no willingness to invite him. Example (18) can pragmatically be interpreted as absence of volition, with the negation in there was no question of transferred to the implied modal notion of willingness. Likewise, there is no question of in (19) invites modal meanings of impossibility (with the fallen horse surrounded by traffic one cannot first debate how he came to fall) or absence of permission (pity with the overworked horse ethically forbids not getting him up). Here too, the negation in the matrix applies to the proposition in the complement clause. In fact, on their grammaticalized readings, (18) and (19) have what is known as NEG-raising, i.e. the negation applies to the complement clause. This “necessarily goes with grammatical, inherently nonaddressable CTP [complement-taking-predicate, K.D., SD] variants” (Boye & Harder 2007: 578). (17) There’s no question of the divine afflatus; that belongs to another sphere of life. (CLMETEV, 1850-1920) (18) Marian, however, visited them at their lodgings frequently; now and then she met Jasper there. The latter never spoke of her father, and there was no question of inviting him to repeat his call. (CLMETEV, 1850-1920) (19) When in the streets of London a Cab Horse, weary or careless or stupid, trips and falls and lies stretched out in the midst of the traffic there is no question of debating how he came to stumble before we try to get him on his legs again. (CLMETEV, 1850-1920) These examples show how there is no question acquired negative value: it conveyed (or allowed to infer) the negation of modal notions such as possibility, permission or volition. The resulting reading is a statement in which a deontic-dynamic concept is negated: all these examples pertain to possible or desirable actualization of actions (Lyons 1977: 823). In the emergence of the negative modal marker use, lexicalization and grammaticalization are again tightly entwined. The meaning of the idiom ‘not be raised as an issue’ shifted to negation of dynamic or deontic modality. Example (20) shows that the negative modal marker use of there be no question could also be followed by finite clauses in Late Modern English. (20) there was no question that he personally was to capture and fight the great machine. (CLMETEV, 1850-1920) In (20), the proposition contains the dynamic modal was to expressing subjectinherent necessity (Palmer 2001), which is negated by there was no question. 3.4. Present-day English For Present-day English, we follow up only the patterns with no question, as it was these that acquired grammatical modal meaning in Late Modern English. The main aim of this section is to systematize the functional-structural patterns realized by clauses with no question in Present-day English, to complete the developmental picture traced in the previous sections. Our 250 token random sample contained 228 clauses, with the existentials dominating strongly with 226 tokens. They appeared almost exclusively sentence-initially, viz. in 97.3%. The remaining two clausal structures contained I have no question followed by a prepositional phrase with about. The discussion of the data sample will focus on the existential examples. Table 2 represents the distribution of lexical(ized) and grammaticalized uses across the sample. Uses lexical noun + complement clause lexical ‘unchallengeable’ lexical ‘not at stake’ positive modal: epistemic positive modal: dynamic/deontic negative modal: dynamic/deontic negative modal: epistemic TOTAL n 2 28 40 76 10 44 25 226 % 1 12.5 17.5 34 4.5 19.5 11 100 Table 2: Uses of there-clauses in WB sample The smaller proportion of existential examples, 74, or 33%, involve lexical uses. In two, we find a pattern not attested in the historical data: the lexical noun question as such (not as part of a composite predicate) sanctions a complement clause. Using noun complement clauses, Example (21) from our sample describes an educational policy document about maths teaching: it does not contain any question addressing whether the child understands the concept, but merely statements about children learning to read and recognize digits. (21) There are statements that a child will be able to read and recognise a four-digit number for example but no question on whether the child understands the concept." (WB) All the other examples have the lexicalized semi-fixed idioms that emerged in Early and Late Modern English. The ‘not be challengeable’-idioms, which appeared around 1700, form 12.5% of the sample. The notion or proposition potentially under challenge is still expressed either by a prepositional phrase, as in (4) above, or a clausal complement, e.g. (22). The primary status of the idiom in the utterance is typically brought out by contrastive or equivalent assertions in the discourse context. In (4) the army’s usual wariness of soldiers crying off sick is contrasted with their not questioning Tolkien’s condition, which is hence addressable: was there really no question of his condition? (Boye & Harder 2006: 581). In (22) the exclusion of doubt expressed by there was no question is preceded by equivalent make certain. (22) To make certain, we continued until there was no question that what we were looking at was the runway. (WB) The ‘not be an issue’-idioms, which emerged around 1850, account for 17.5% of the sample. They take nominal complements, as in (5), in a majority of cases (90%). Clausal complements, as in (23), are very restricted (10%). In these examples, the meaning of an idea not being (raised as) an issue is also supported by contextual elements such as and there never was any question in (23). (23) He said: `Craig is under contract until the end of the next World Cup campaign, and that won't change. There's absolutely no question of him leaving, and there never was any question no matter what happened at Wembley. (WB) The grammaticalized modal uses of the existential pattern form, with 152 out of 226, the majority of our sample. They have come to realize in Present-day English a full-fledged system of modality-cum-polarity. Their polarity value has crystallized in a systematic association with complement types: there be no question + (that) + finite clause functions as positive emphatic marker and there be no question of + gerund functions as negative marker. These are the systematic correlations between polarity and complement types identified by Kjellmer (1998) for Present-day English. The fledgling extension of finite complements to the negative marker observed in Late Modern English (example 20) seems not to have persisted. Importantly, both polarity types can now modify either epistemic or deonticdynamic statements. The positive marker uses, which started off modifying truth claims, had already extended to desired actions in Late Modern English, as in (16). This extension is confirmed in our Present-day English data, with examples such as (2) above, There is no question he must stay, even though epistemic claims remain the more common option, viz. 76 tokens versus 10 dynamic-deontic statements. The negative modal marker there be no question of + gerund, which had started off conveying deontic-dynamic meanings, have come to also convey epistemic meanings, as in (3) above, There’s no question of Her Majesty turning up on your doorstep unannounced. Epistemic uses were not attested in our Late Modern English data, but in the present-day sample total 25 tokens against 44 deontic-dynamic uses. The two possessive clauses with prepositional phrase, e.g. (24), in our sample are lexical uses in which have no question means ‘not challenge’, much like the there be no question-idiom illustrated in (12). However, a quick search on the Internet reveals that I have no question is also used in a secondary, grammaticalized way, in which it approaches the status of a positive epistemic modifier, e.g. (25). The same holds for copular matrices: the Internet contains examples like (26) in which they function as a parenthetical expressing strong certainty. (24) I have met many homosexuals with equally unshakable masculine gender identity. They have no question about their maleness. (WB) (25) Had he played a full year, I have no question he'd have been the consensus #1. (http://forums.rotoworld.com/index.php?/topic/267200-kyrie-irving-20112012/page__st__40) (26) Christ suffered for us, it is no question, .. .(http://biblelight.net/gospel-2.htm) Referring back to the historical data, we can see I have no question as the expression that took over the grammaticalized uses from obsolete I make no question in (14). And, whereas the copular clauses were still used mainly propositionally in Late Modern English, e.g. (15), they have now established clearly grammaticalized uses. A casual Internet search did not reveal any examples of possessives or copulars with no question qualifying deontic statements and they are definitely not used with negative polarity value. The possessive and copular clauses thus have not developed anything approaching the extended system of polar and modal values of there’s no question. 3.5. Differences between lexicalization and grammaticalization In the previous sectiosn we have seen that the distinction between lexicalization and grammaticalization is crucial to the developmental paths of clausal expressions with (no) question. There is a general consensus that grammaticalization and lexicalization share many features, which makes it difficult to differentiate the one from the other (Lehmann 2002, Brinton & Traugott 2005). Both affect larger syntagms, not individual items, and involve semantic erosion, fusion and fixing of the component elements. However, according to Lehmann (2002: 13), a grammaticalized unit is accessed “analytically”, whereas lexicalized units are accessed “holistically”, because its internal relations have “become irregular and get lost” (2002: 13). On this view, ‘lexicalization’ applies only to complex forms becoming unanalyzable wholes as in fossilization and univerbation (Himmelmann 2004: 28). A broader view of lexicalization can be based on the approach to idiomatic patterns advocated by Sinclair (1991: 110), Nunberg, Sag & Wasow (1999) and Langacker (1999: 344) amongst others. They point out that many idioms are only semi-fixed and tend to keep a degree of analyzability and internal variability. These insights bear, in our view, also on the diachronic process of lexicalization. To define and recognize lexicalization, we take the result of the process of change as criterial. If change produces a linguistic element with a specific contentful meaning, functioning as a lexical item, we consider it lexicalization31. We have seen that in the formation of idiomatic patterns with light verb and deverbal noun such as make a/Ø question, there be a/Ø question, the NP keeps some of its modification possibilities (e.g. choice of determiner), adverbs may be added, e.g. never any question, and the verb can vary too, e.g. make/have no question. In our discussion of the data, we have made the distinction between grammaticalization and lexicalization mainly on the basis of differences on the syntagmatic axis. We have followed Boye & Harder’s (2007) criteria for distinguishing between lexical and grammaticalized uses of complement-taking predicates on the basis of their having primary or secondary discourse usage status. Giving full weight to the discourse context, we applied tests relating to ‘addressability’ such as really-queries, tags, NEG-raising, and modification by a subordinate clause, e.g. (15), (25). Useful as these syntagmatic tests are for distinguishing lexicalized from grammaticalized uses, they do not constitute the whole picture. Linguistic patterning is not only present on the syntagmatic, but also on the paradigmatic axis. We want to argue that the fundamental differences between lexicalization and grammaticalization lie, besides primariness and secondariness in discourse usage, in the different paradigmatic relations contracted by elements that have become lexical or grammatical. We therefore first have to elucidate the different types of paradigmatic configurations that lexical items and grammatical elements are defined by. We adhere to the (neo-)Firthian view that it is an essential feature of lexical items that they impose collocational constraints on the lexical items they co-occur with, 1 This is the definition of lexicalization proposed by Blank (2001:1603). The main alternative approach makes features of the process of change itself criterial (see Himmelmann 2004, Brinton & Traugott 2005). For Trousdale (forthc.), these are a decrease in generality, a decrease in productivity, and no change, or decrease, in the compositionality of the construction. and, as members of lexical sets, colligational constraints on specific syntactic structures they pattern with. As rightly stressed by Sinclair (1991), lexical meaning does not reside solely in the lexical ‘node’. Rather, the semantic structure of a lexical item is determined by its coselection of specific (sets of) collocates. This is a distributional view of lexical meaning, according to which the collocates are diagnostic of a lexical item’s meaning. For instance, (partial) synonymy can be established in terms of similarity between collocate clouds (e.g. De Deyne, Peirsman & Storms 2009). Petré, Davidse & Van Rompaey (forthc.) have applied this thinking to the strings be on (the/one’s) way/road to, which have lexicalized composite predicate uses (meaning ‘go to/head for + spatial goal’) and grammaticalized aspectual uses (which mean ‘be going to + action/state/event’). Extensive corpus-based study showed that the composite predicate uses clearly behave as lexical items in imposing the coselection of spatial goals or coercing this meaning onto action-state-event goals (such as be on one’s way to work/a party, etc). As is typical of (largely) synonymous lexical items, they share many collocational restrictions while still displaying distinct preferences. Be on the/one’s road to co-occurs mainly with names of towns and with the fixed phrase road to nowhere. This can be explained by the persistence of road’s very concrete lexical meaning of “An ordinary line of communication used by persons passing between different places” (OED2). Be on the/one’s way to, by contrast, collocates with more diversified spatial nouns, which may be towns, countries, continents, or landmarks such as the airport, the coast and a quarter of their collocates are action-state-event nouns such as incident, picnic, etc. This more diversified distribution of collocates is probably motivated by the more abstract meaning of way, viz. “course of travel or movement” (OED2). In contrast with composite predicates such as be on the/one’s road/way to, whose lexical semantics predispose them to spatial collocates, the semi-fixed idioms with (no) question impose, like the corresponding simple predicates ask, question, clear colligational restrictions, that is, they predict co-occurrence with specific syntactic structures4. As is to be expected of lexical uses of complement-taking predicates describing locutions, they take either prepositional phrases specifying the ‘matter’ (Halliday 1994: 157) being asked about or questioned, or clausal complements, typically of the reported question type. These colligational patterns are motivated by a general semantic feature in the predicate, e.g. ‘ask’, which needs to be completed by the specific content of the complement (Langacker 1999: 28), e.g. ‘about x’, ‘whether or not x’. In this respect, the idioms with (no) question behave wholly like the lexical uses of simple complement-taking predicates, which argues for viewing their formation as lexicalization5. We now turn to the question what form of paradigmatic organization characterizes grammatical elements. To answer this, we turn again to the Firthian tradition, more specifically, Halliday’s (1992) thought about the paradigmatic organization of the grammar. Halliday views the oppositions within a grammatical paradigm not so much as obtaining between its members, as in the tradition of Jakobson (1971 [1939]), but, at a more abstract level, as obtaining between semantic features associated with the members. By conceiving of systemic oppositions in terms of features, it is possible to capture the interdependencies between features from different systems. Which terms of one system combine with the terms of another system is constitutive of the larger grammatical system. We noted in Section 3.4 that in Present-day English the positive and negative modal markers have both come to combine with either epistemic or deontic-dynamic modality. We are now in a position to explicate the systemic changes involved in this. In Late Modern English, the grammaticalized clausal there-structures presented language users with the possibility of expressing the following combinations of terms from polarity and modality: positive + epistemic there’s no question (that) external negation + dynamic/deontic there’s no question of Figure 1. Meaning options for there’s no question that/of in Late Modern English There’s no question + finite clause realized a positive epistemic qualification of a proposition, as in (13). There’s no question of + gerund conveyed external negation of dynamic-deontic qualifications of non-actualized situations, e.g. (18), (19). The latter combination illustrates a typical systemic interdependency. It is characteristic of the dynamic-deontic notions of possibility, permission and volition that they take external negation, which cancels the modality. As we saw, the modal reading of (18) There was no question of inviting him is ‘there was no willingness to invite him’. The negation is external in that it bears on and negates the modal notion of willingness. In the period from the end of Late Modern English to Present Day English, the grammaticalizing expressions extended to the modal types they had not previously associated with. Positive marker there’s no question that extended to deontic statements and negative marker there’s no question of to epistemic statements. As a consequence, the latter was dis-sociated from its exclusive combination with external negation. as illustrated by (3), There’s no question of Her Majesty turning up on your doorstep (‘there is (near-)certainty that Her Majesty will not turn up on your doorstep’).The negation is internal to the proposition being qualified as near-certain. Moreover, there’s no question of is now also found taking complements with negation, expressing by virtue of this double negation, emphatically positive dynamicdeontic notions, e.g. possibility in (27), or strongly positive truth claims, as in (29). (27) when they showed me the X-ray which revealed only a small break, I knew there was no question of me not being able to play again. (WB) (28) I am certain David will have some strong races for us. There’s no question of him not being given identical equipment to Kimi or the full backing of the team. (WB) Likewise, there’s no question that is now no longer exclusively associated with the expression of positive modal values. It can be followed by a clause containing a negation, expressing internally negated epistemic modality (29) or externally negated dynamic modality, e.g. absence of volition (30). (29) ... there is absolutely no question, we didn't deserve to win that match. (WB) (30) There’s no question, no question. I’ll not mince my words. (WB) What we witness here by way of change is “the dissociation of associated variables” and “their subsequent combination” (Halliday 1992: 30) into a richer paradigmatic resource, providing the language user with semantic possibilities that have much increased for both there’s no question that (Figure 2) and there’s no question of (Figure 3). epistemic* dynamic/deontic positive* internal negation negative external negation Figure 2: Meaning options for no question that in Present-day English dynamic/deontic* epistemic negative external negation* internal negation positive Figure 3: Meaning options for no question of in Present-day English The options available for the two grammaticalized there-clauses now approximate the possible combinations of semantic features codable by core modal expressions such as auxiliary will, which can express both epistemic and dynamic/deontic meanings, positive and negative polarity, and within the latter, internal and external negation. However, with there be no question that/of, a number of the features are still marked and infrequently chosen. The most common, unmarked meaning options are starred in Figures 2 and 3, revealing as default combinations epistemic + positive for there’s no question that and dynamic/deontic + external negation for there’s no question of, i.e. the grammatical meanings that first became conventionally associated with the patterns. Time will have to tell whether the probabilities of choice will eventually come to coincide with those of established modal expressions. In any case, the changes just outlined involve what one might call increased ‘systemicness’. The grammaticalizing strings come to code more and more the abstract paradigmatic meaning potential of core grammatical expressions. In this sense, they offer a particularly clear example of progressive grammaticalization. On this view, grammaticalization is not only about an expression acquiring one particular grammatical meaning, but coming to express more and more combinations of grammatical features. Grammaticalization is then also revealed to be a process in which the acquisition of coding possibilities in one system is tied up with the acquisition of coding possibilities in other systems. If this sort of process of change can be observed, we are clearly dealing with grammaticalization, not lexicalization. Lexicalization does not have systemic effects, as noted by Brinton & Traugott (2005). We thus propose that increased systemicness is constitutive of grammaticalization.6 5. The emergence of adverb no question The modal adverbial no question appears in the period between 1570 and 1640. Their meaning is epistemic, with this modal notion understood “not only ... from a truthfunctional point of view ... but from a rhetorical point of view” (SimonVandenbergen 2007: 30). The speaker certainty attaching to the propositions is variable, see-sawing between certainty, as in (31), and probability, as in (32), where modal will and in probability support a probability reading. All the adverbials have positive orientation. (31) he will trade at sea as a merchant and hath innobled thereby that qualytye and will no question in probabilytye be much more powerfull at sea (PPCEME, 1570-1640) (32) the most active or busie man that hath been or can bee, hath no question many vacant times of leisure (PPCEME, 1570-1640) That the adverb emerges at this point pleads against the hypothesis of its development out of clausal structures. At that time, as shown in section 3.2, the different matrices with question did not show any specialization for negative contexts yet. In fact, there is not one single instance of a matrix containing no question before the first adverbial data. Hence, a more acceptable explanation for the adverb is a contemporaneous emergence with other adverbials containing the same noun. Without any question (33) and out of question (34) also occur for the first time between 1570 and 1640. They have a comparable meaning, signalling that the proposition they relate to is very likely or even certain. (33) he that doth assemble Power, if the King doth command him upon his Allegiance to dissolve his Company, and he continue it, without any question it is High-Treason. (PPCEME, 1570-1640) (34) Out of question they be innumerable which receiue helpe by going to the cunning men. (PPCEME, 1570-1640) It therefore seems more plausible that no question, without question and out of question emerged by analogy with adverbials like no doubt, without doubt and out of doubt, as well as no way and no wonder, which are attested two to three centuries earlier in the OED and which were already entrenched in Early Modern English. They all instantiated the schema (Langacker 1999: 261-288) ‘negation + modal noun’.7 The presence of this set of similar adverbial constructions may well have triggered (Traugott 2008) the emergence of the adverbials with negation + question. The relations with the entrenched adverbials and amongst the various adverbials with question appear to have been complex. Without question and out of question all figure sentence-initially, while no question occurs exclusively in medial position in Early Modern English. It moved towards final position in Late Modern English, the position it typically takes in Present-day English. There are indications of a more specific relation of analogy between no doubt and no question on account of their similarity in terms of position and meaning. In Early Modern English, when no question emerged in medial position, no doubt had just moved to medial position from the initial position it occupied in Middle English, and both could convey either probability or certainty in that period (De Wolf 2010: 38). In Present-day English, the adverbial form no question is relatively rare in comparison with the clausal structures, accounting for only 8.8 % as opposed to 91.2 % of clauses in our 250 token sample. All 22 hits in the sample are sentence-final, the position it had shifted to in Late Modern English. The majority of these examples are added as parentheticals, as in There will be changes on Saturday, no question (WB) (1). No question grants the proposition extra emphasis and in Present-day English always has the meaning of certainty, as shown by paraphrases such as absolutely or definitely. 6. Conclusion We set out in this diachronic-synchronic study of (there’s) no question with two descriptive research questions. Regarding the clausal structures, mainly existential ones, our aim was to reveal the paths of change that led to their current idiomatic and grammaticalized uses. For the adverbial, we wanted to find out if it developed via ellipsis from the clausal structures. Diachronic study of the adverbial forms with question revealed that the adverb emerges later than the clauses. However, the absence of clauses with negation invalidates the hypothesis that the adverb is the result of ellipsis of the matrix clause. The first occurrence of the phrase no question is in fact in the adverbial form in Early Modern English. We suggested that no question, without question and out of question probably emerged by analogy with adverbials like no doubt, without doubt and out of doubt, as well as no way and no wonder, which were already entrenched in Early Modern English. The first attestations of question with complement clauses in Middle English and Early Modern English were in composite predicates such as make question and lexicalized clauses such as there be question, which first meant ‘ask’ and then ‘challenge’. In addition, there be question also acquired the meaning ‘be at issue’. In Late Modern English, these two idiomatic patterns specialized for negative contexts with the senses ‘be unchallengeable’ and ‘not be at issue’. It was these idiomatic patterns that grammaticalized, resulting in positive modal content clauses and negative modal markers respectively. The existentials with no question thus clearly show how lexicalization can be a crucial step towards grammaticalization, not only structurally, but also semantically and pragmatically. This diachronic reconstruction also showed the importance of distinguishing lexicalized from grammaticalized uses, a theoretical issue high on the agenda in current grammaticalization studies. In this debate it is essential, we argued, to spell out differences both in syntagmatic and paradigmatic patterning. On the syntagmatic axis, we followed Boye & Harder’s (2007) recognition criteria for distinguishing lexica(lized) from grammaticalized uses on the basis of their having primary or secondary status in discourse usage. On the paradigmatic axis, we proposed that a lexicalized item imposes lexicosemantically motivated collocational and colligational relations, while grammaticalizing elements come to express more and more meaning options, with their typical interdependencies, from grammatical systems. The grammaticalized no question clauses are a good example of Halliday’s claim that the dissociation of associated variables and the recombination of the independent variables is an important ‘semogenic’ process, i.e. a process of change creating coding possibilities for an enriched semantic resource (Halliday 1992: 27). References Blank, Andreas. 2001. Pathways of lexicalization. In Martin Haspelmath et al (eds.) Language typology and language universals. Vol. II. 1596-1608. Berlin: de Gruyter. Boye, Kaspar & Peter Harder. 2007. Complement-taking predicates: Usage and linguistic structure. Studies in Language 31. 569-606. Brinton, Laurel. 2008. The comment clause in English. Syntactic origins and pragmatic development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Brinton, Laurel & Elizabeth Traugott 2005. Lexicalization and language change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. De Deyne, Simon, Yves Peirsman & Gerrit Storms. 2009. Sources of semantic similarity. In Niels Taatgen & Hedderik Van Rijn. (eds.), Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society. 1834-1839. Austin, Tx: Cognitive Science Society. De Wolf, Simon. 2010. A question of no doubt. A synchronic-dianchronic account of no doubt, no question and related expressions. Unpublished MA-thesis. University of Leuven: Linguistics Department. Diewald, Gabriele & Elena Smirnova. Forthc. “Paradigmatic integration”: the fourth stage in an expanded grammaticalization scenario. In Kristin Davidse et al (eds.), Grammaticalization and language change: origins, criteria and outcomes. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Firth, John. 1951/1957. Models of meaning. Papers in linguistics 1934-1951 (1957). London: Oxford University Press. Jakobson, Roman. 1971 [1939]. Signe zéro. In Selected writings. Volume 2: Word and Language, 211-219. The Hague: Mouton. Halliday, Michael. 1992. How do you mean? In Martin Davies & Louise Ravelli (eds.), Advances in systemic linguistics. Recent theory and practice, 20-35. London: Pinter. Halliday, Michael. 1994. An introduction to functional grammar. 2nd ed. London: Arnold. Himmelmann, Nikolaus. 2004. Lexicalization and grammaticization: opposite or orthogonal? In Walter Bisang et al (eds.). What makes grammaticalization – a look from its components and its fringes, 21–42. Berlin: Mouton. Hopper, Paul & Elizabeth Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kiparsky, Paul & Carol Kiparsky. 1971. Fact. In Semantics: An interdisciplinary reader in philosophy, linguistics and psychology, Danny Steinberg & Leon Jakobovits (eds.), 345-369. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kjellmer, Göran. 1998. No Question. English Studies 79. 462-468. Langacker, Ronald. 1999. Grammar and conceptualization. Berlin: Mouton. Lehmann, Christian. 2002. New reflections on grammaticalization and lexicalization. In Ilse Wischer & Gabriele Diewald (eds.), New reflections on grammaticalization, 118. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Nunberg, Geoffrey, Sag, Ivan & Wasow, Thomas. 1994. Idioms. Language 70: 491538. Palmer, Frank. 2001. Mood and modality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Petré, Peter, Kristin Davidse & Tinne Van Rompaey. 2012. On ways of being on the way: lexical, complex preposition, and aspect marker uses. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17. OED: Oxford English Dictionary. 1933. James Murray et al (eds.) Oxford: Oxford University Press. OED2: The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd Ed. 1989. John Simpson & Edmund Weiner (eds). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Simon-Vandenbergen, Anne-Marie. 2007. No doubt and related expressions. A functional account.’ Michael Hannay & Gerard Steen (eds). Structural-functional studies in English grammar: in honour of Lachlan Mackenzie, 9-34. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Sinclair, John. 1991. Corpus, concordance and collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Traugott, Elizabeth. 2008. Grammatikalisierung, emergente Konstructionen und der Begriff der “Neuheit”. In Kerstin Fischer & Anatol Stefanowitsch (eds.), Konstruktionsgrammatiek II: Von der Konstruction zu Grammatik, 5-32. Tübingen: Stauffenburg. Trousdale, Graeme. 2012. Grammaticalization, constructions and the grammaticalization of constructions. In Kristin Davidse, Tine Breban, Lieselotte Brems & Tanja Mortelmans (eds.), Grammaticalization and language change. New reflections. Amsterdam: Benjamins. 165-196. Robins, Robert. 1980. General linguistics. An introductory survey. London: Longman. 1 We sincerely thank the three anonymous referees for their generous suggestions and insightful comments, which suggested many extra dimensions to this study in comparison with the first version. We also thank Srikant Sarangi for his helpful handling of the editorial process. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Interuniversity Attraction Poles programme (Belgian Science Policy Office, project P6/44) Grammaticalization and (Inter-)Subjectification and by the GOA-project 12/007, The multiple functional load of grammatical signs, awarded by the Leuven Research Council. 2 All examples followed by (WB) were extracted from WordbanksOnline and are reproduced here by permission of HarperCollins. 3 This is the definition of lexicalization proposed by Blank (2001:1603). The main alternative approach makes features of the process of change itself criterial (see Himmelmann 2004, Brinton & Traugott 2005). For Trousdale (forthc.), these are a decrease in generality, a decrease in productivity, and no change, or decrease, in the compositionality of the construction. 4 Firth defined colligation as groups of words considered as members of word classes predicting a relation of syntactic structure (Robins 1980: 178). 5 A partly different approach to composite predicates is proposed by Brinton & Traugott (2005). They suggest that there are two classes of composite predicates: relatively lexical ones such as curry favor with, cast doubt on, and relatively grammatical ones, e.g. make a remark, take a walk, give a kiss, which involve aspect. This position is in keeping with Trousdale (forthc.) who views composite predicates such as have a bath as resulting (more) from grammaticalization but ones such as give a roasting, from lexicalization. 6 This proposal is comparable in spirit to, but also different from Diewald & Smirnova’s (forthc.) views on paradigmatizatic integration, which they argue is what distinguishes grammaticalization from lexicalization. Paradigmatic integration involves grammaticalizing items slotting into existing grammatical paradigms, and also falling into the systemic oppositions and the unmarked-marked contrasts between the members of the paradigm (Jakobson 1971 [1939]). By contrast, Halliday (1992) views the opposing terms in the systems as the abstract features being encoded and focuses on the interdependencies between systems. 7 Traugott (2008) refers to a set of similar substantive (partially lexically filled) constructions as a mesoconstruction.