Supplementary Information (doc 84K)

advertisement

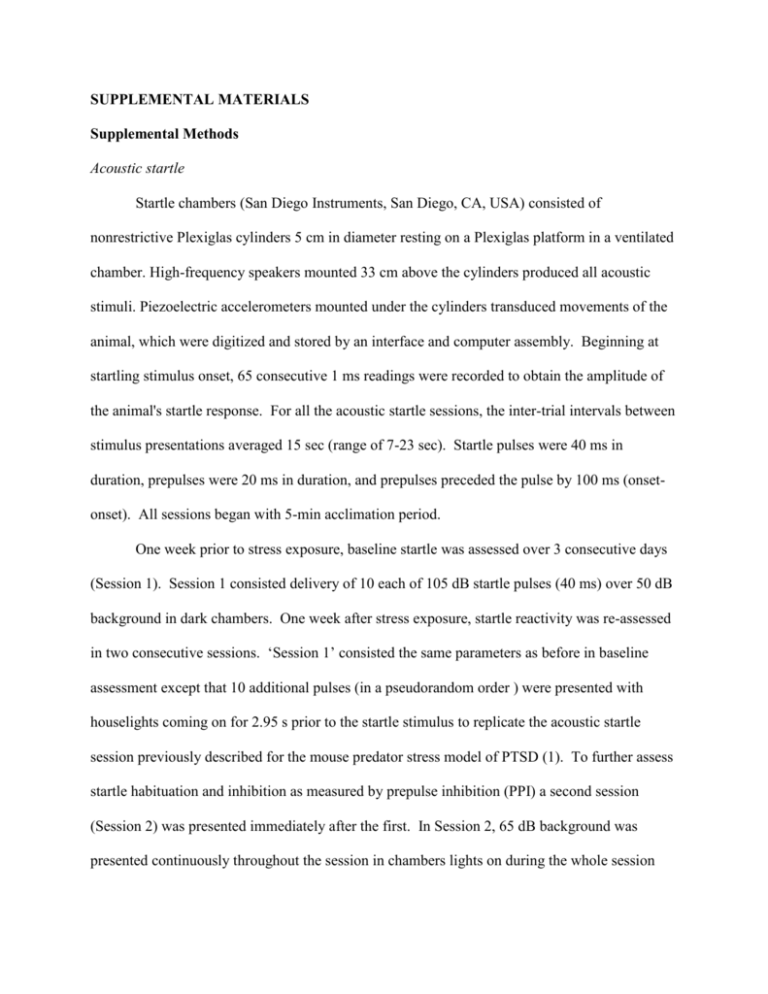

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS Supplemental Methods Acoustic startle Startle chambers (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA) consisted of nonrestrictive Plexiglas cylinders 5 cm in diameter resting on a Plexiglas platform in a ventilated chamber. High-frequency speakers mounted 33 cm above the cylinders produced all acoustic stimuli. Piezoelectric accelerometers mounted under the cylinders transduced movements of the animal, which were digitized and stored by an interface and computer assembly. Beginning at startling stimulus onset, 65 consecutive 1 ms readings were recorded to obtain the amplitude of the animal's startle response. For all the acoustic startle sessions, the inter-trial intervals between stimulus presentations averaged 15 sec (range of 7-23 sec). Startle pulses were 40 ms in duration, prepulses were 20 ms in duration, and prepulses preceded the pulse by 100 ms (onsetonset). All sessions began with 5-min acclimation period. One week prior to stress exposure, baseline startle was assessed over 3 consecutive days (Session 1). Session 1 consisted delivery of 10 each of 105 dB startle pulses (40 ms) over 50 dB background in dark chambers. One week after stress exposure, startle reactivity was re-assessed in two consecutive sessions. ‘Session 1’ consisted the same parameters as before in baseline assessment except that 10 additional pulses (in a pseudorandom order ) were presented with houselights coming on for 2.95 s prior to the startle stimulus to replicate the acoustic startle session previously described for the mouse predator stress model of PTSD (1). To further assess startle habituation and inhibition as measured by prepulse inhibition (PPI) a second session (Session 2) was presented immediately after the first. In Session 2, 65 dB background was presented continuously throughout the session in chambers lights on during the whole session and it included five blocks beginning with the delivery of five each of 120 dB startle pulses (Block1) allowing startle to reach a stable level before specific testing. The second block tested response threshold and included four each of five different acoustic stimulus intensities: 80, 90, 100, 110 and 120 dB in a pseudorandom order. The third block consisted of 42 total trials consisting of twelve 120dB startle pulses and ten each of three different prepulse intensity trials (69, 73 and 81 dB 20 ms prepulse preceding a 120 dB pulse with 100 ms from prepulse to pulse onset) to assess PPI. The fourth block totaled 28 trials consisting of eight 120dB startle pulses and four each of five different prepulse-pulse onset trials (i.e. interstimlus interval (ITI): 73 dB prepulses preceding 120 dB pulses by 25, 50, 100, 200, or 500 ms) to assess PPI with different ITI intervals. The session ended with five pulses of 120 dB (Block 5) to assess habituation of the startle response. Prepulse inhibition (PPI) was calculated as percent change compared to 120 dB pulses without prepulse using 120 dB alone trials in Block3 using the following formula: %PPI=(100-(average startle magnitude in prepulse trial/average startle magnitude to pulse alone trial)*100). Habituation was measured by comparing the response to 120dB pulses across 5 blocks in the session. In all experiments, the average startle magnitude over the record window (i.e., 65 msec) was used for all data analysis. Composite avoidance (z-)score analysis We calculated and analyzed composite avoidance scores, which is a common method to create an overall index of different symptoms in clinical research when multiple measures (subdimensions) of the same construct are conducted. First, we calculated z-scores of time spent in the aversive arenas (i.e. center of open field; light compartment of light-dark box; 3-cm radius zone near the tube filled with cat litter) using the following formula: (individual score – average of the whole experimental cohort) / standard deviation of the whole experimental cohort Z-scores were calculated for each test separately for males and females because of significant effects of sex. To create composite z-scores, we used two methods: (1) we averaged z-scores of the above avoidance tests, or (2) calculated weighted composite z-scores based on their factor loadings in a preceding factor analysis of the three individual tests. Accordingly, composite z-scores represent overall avoidance (of three tests) by indicating group values normalized for the whole same-sex cohort (z-score=0). We added these variables in order to determine overall effect size of stress x CRH, and reduce family-wise error, and hence, reduce the probability of false positive outcomes generated by repeated testing. qRT-PCR Crf1 (Mm00432670_m1), Crf2 (Mm00438303_m1), and Fkbp51 (Mm00487401_m1) were assessed using commercially available primers (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). First, RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy Lipid Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. On-column DNase digestion was performed using the RNase-Free DNase Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quantity and quality was measured using a Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) and total RNA across each sample was standardized and used for first-strand cDNA synthesis using the Superscript III first-strand kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). TaqMan quantitative PCR (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) was performed at the UCSD core facility (http://cfar.ucsd.edu/). Supplemental Results Table S1. Locomotor and exploratory activity over 30 min in the mouse BPM. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05 (main effect of stress or CRFOEdev in three-way ANOVA test); CRFOEdev: transient CRF over-expression before puberty. CRF Stress Handled Male Control Stressed Handled Male CRFOEdev Stressed Handled Female Control Stressed Handled Female CRFOEdev Stressed Main effect of stress: Main effect of CRFOEdev: Distance travelled (cm) 4494 ± 93 4169 ± 100 5217 ± 130* 4449 ± 132* 4951 ± 195 4916 ± 150 5897 ± 233* 6136 ± 233* F(1,66)<1, ns F(1,66)=5.50, p=0.022 Number of rears 100.0 ± 25.1 81.7 ± 24.3 87.1 ± 30.8 95.5 ± 37.0 60.4 ± 24.6 73.0 ± 34.0 67.0 ± 30.1 66.3 ± 26.0 F(1,66)<1, ns F(1,66)<1, ns Number of hole-pokes 56.2 ± 25.2 43.4 ± 18.8* 43.6 ± 22.6 37.4 ± 18.7* 43.4 ± 23.3 28.6 ± 13.1* 49.9 ± 22.3 33.8 ± 18.9* F(1,66)=8.20, p=0.006 F(1,66)<1, ns Table S2. The intensity of predators stress during a 10-minutes-long interaction. UpperData are presented as mean ± SEM. CRFOEdev: transient CRF over-expression before puberty. There is no singificant difference between sexes, or controls and CRHOE groups. Time duration (s) of: Near the mouse (<1 ft) Sniffing Pawing Mouthing Male Control 383.3 ± 28.2 2.7 ± 2.1 157.0 ± 9.8 51.9 ± 20.8 Male CRFOEdev 360.0 ± 52.7 5.0 ± 2.0 149.5 ± 21.5 57.7 ± 18.5 Female Control 389.8 ± 29.3 1.2 ± 0.7 176.9 ± 14.1 52.0 ± 14.1 Female CRFOEdev 388.5 ± 24.1 2.2 ± 1.0 174.2 ± 11.8 41.3 ± 7.9 Frequency of: Near the mouse (<1 ft) Sniffing Pawing Mouthing Male Control 14.7 ± 1.5 3.3 ± 2.1 63.8 ± 6.4 28.0 ± 8.4 Male CRFOEdev 13.4 ± 2.7 3.8 ± 1.6 59.2 ± 10.6 27.5 ± 7.2 Female Control 15.8 ± 2.1 1.6 ± 1.0 64.7 ± 6.6 29.0 ± 6.1 Female CRFOEdev 17.8 ± 1.5 1.7 ± 0.6 68.8 ± 5.3 27.3 ± 3.8 Males Females 80 Average Startle Magnitude Average Startle Magnitude 100 80 60 40 20 60 40 20 0 0 Pre-stress Pre-stress Post-stress Post-stress Control CRFOE * Fig.S1. Average startle magnitude exhibited in Session 1 in dark chambers (105 dB) before and after predator stress. Data are collapsed across handled and predator stressed groups since stress did not affect startle magnitude (Fstress(1,66)<1, p>0.674). In contrast, CRFOE increased the magnitude of the reaction in both sexes indicated by three-way ANOVA test (*p<0.01 main effect of CRFOEdev). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. CRFOEdev: transient CRF overexpression before puberty. Supplemental References 1. Adamec R, Fougere D, Risbrough V (2010): CRF receptor blockade prevents initiation and consolidation of stress effects on affect in the predator stress model of PTSD. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology / official scientific journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum. 13:747-757.