Language, Thought and Consciousness

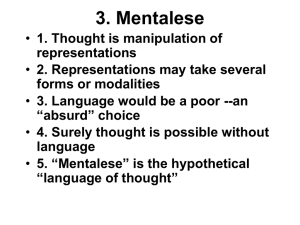

advertisement

Language, Thought and Consciousness By Peter Carruthers Cambridge University Press. 1996. xv + 291pp. $49.95 cloth Carruthers aims to establish the possibility that we often think in the same language that we speak. Not a difficult task, you may think. Doesn’t introspection reveal an inner soliloquy, a stream of sentences formed in the acoustic imagination? But according to a venerable tradition - Carruthers calls it the communicative conception of language - natural language is something akin to a code. We do not think in natural language, we translate our thought into natural language when we want to make it publicly available, or in the case of conscious inner verbalizations, when we want to make a note to ourselves for future reference. A currently influential version of the communicative conception is due in large part to Fodor: cognition consists primarily in the manipulation of sentences of Mentalese, an innate, universal symbol system. Carruthers thinks this is wrong: we do a good deal of our thinking in natural language itself. He calls this the cognitive conception of natural language. The case for Mentalese has a number of strands. Some of these are observations of the commonplace. Natural language sentences can be ambiguous “That stool is horrid” - yet since we know what we mean when we utter them, this suggests our thinking is not being conducted in natural language. Then there is the tipof-the-tongue phenomenon: we sometimes have a thought we want to express, but cannot find the words in natural language to express the thought. There are more theoretical grounds. Sentences in different natural languages can express the same propositions, the same thoughts or beliefs. A natural explanation: they express the same Mentalese propositions. Chomsky has shown that natural languages have a common form, at a certain level of abstraction - this fits neatly with the Mentalese hypothesis. Fodor argues that holism about meaning is incompatible with realism about folk psychology; to be realists we need to have an atomistic semantics, i.e. in specifying the meaning of a given mental state we will not mention any other mental state. The only language for which an atomistic semantics can be given is Mentalese Fodor’s own causal co-variance theory fits the bill. Perhaps most telling of all, it seems obvious that natural language isn’t needed for thought: look at the way animals and human infants behave. They clearly engage in a good deal of thinking and reasoning; we can explain their behaviour in terms of beliefs and desires. In the first half of the book Carruthers sets out these issues with exemplary clarity. I know of no finer introduction to them. He does not set out to furnish decisive refutations of every part of Fodor’s position, indeed, he believes Fodor to be right on many counts. Carruthers accepts the computational model of cognition, he believes there are innate mental modules, and that the thinking of some creatures is carried out in Mentalese, or something like it. What he seeks to do, and to my mind successfully, is to show that Fodor’s arguments against the cognitive conception are not decisive: the common-sense view that we do some of our thinking in natural language remains a live option. Which parts of our conscious thinking? He initially seeks to establish that our conscious thinking - that part of it which could be called propositional as opposed to pictorial - is conducted in natural language. This result is then extended. A good deal of our non-conscious thinking is conducted in the medium of natural language (e.g. solving problems while asleep and dreaming of something else). Conscious propositional thought can only be conducted in natural language. Although we may do some of our thinking in Mentalese, the thoughts whose constituent concepts are acquired via natural language can only be entertained in thoughts formulated in natural language. These claims all apply to us humans, in virtue of the laws of nature and the structure of our minds. Perhaps some creatures conduct sophisticated propositional thinking in Mentalese, but if Carruthers is right, we cannot. These results emerge in chapter 8, at the end of the book, after a detour into a comprehensive theory of consciousness, which occupies chapters 5-7. Carruthers accepts that infants and animals engage in genuinely propositional thought. To forge the link between natural language and conscious thought that he wants to establish, he has to establish that creatures lacking natural language are not conscious. Carruthers arguments here lead to the intriguing (astonishing?) conclusion that natural language is naturally necessary for consciousness (for beings whose minds are structured like ours). He is aware of the broader philosophical significance of this: vindication with a vengeance for the Linguistic Turn. In making language the object of their study, philosophers will not merely be investigating the structure of thought, they will also be probing the necessary conditions for consciousness. As he further notes, “If true, this conclusion may have profound implications for our moral attitudes towards animals and animal suffering” (p.221). Carruthers’ theory of consciousness has two elements: a functionalist account of mental concepts, and a version of the higher-order thought theory of consciousness - he calls it “the reflexive thinking theory”. According to the latter, what makes a thought, perception or occurrent belief conscious is the availability of the state to a conscious higher-order thought, (or in the case of beliefs and desires, they are conscious if they are apt to cause the emergence of a conscious thought with the same content as themselves). These higher-order states, should they occur, will be conscious because they too are available to further higher-order states, and so on. His elaboration of this theory is ingenious, and he may be right that his version of the higher-order thought theory is more plausible than the alternatives on offer. But whether any version of the higher-order thought theory is believable is another matter. If the reflexive thinking theory is true, no state is conscious solely in virtue of its intrinsic characteristics. Needless to say, this is highly counterintuitive. The doctrine’s implications are dramatic. Most people believe that infants and animals incapable of reflexive thinking nonetheless have conscious experiences, states which possess phenomenal characteristics. Does a creature need to be able to think about its own experiences in order to feel pain, or see colour? Carruthers’ position would be innocuous if it amounted to a terminological point concerning the use of the adjective “conscious”. But it amounts to more than this: he believes that only conscious states in his sense - can possess phenomenal characteristics. So if he is right, infants and animals - with the possible exception of apes - do not have any experiences. (He wavers at this and suggests that perhaps human infants do have conscious experiences (p.222) but his argument is brief and not very convincing, given his own framework.) Why believe that phenomenal properties are confined to states which can be thought about? Functionalism enters the picture here: “the property of being the subjective feel of an experience ... is a functional one, identical with the possession of a distinctive causal role” (p.214). To have experiences, a creature must be able to think about its experiences as such, i.e. as information-bearing states of itself which may or may not represent the world accurately. I think many will be inclined to draw the line here. Even functionalists need not regard this aspect of the functional role of concepts such as “pain” and “red” to be essential. Those of us who are not functionalists will take a stronger stance. Yes, for a creature to be able to think of its conscious mental states as possessing subjective features, it needs the concept “experience” and all this presupposes. But the properties of an experience we call “subjective” are its intrinsic features; it is these intrinsic properties that are the phenomenal properties, and for a state to have these properties, it is not necessary for its owner to be able to think of them in any particular way. In any event, Carruthers’ views about the relationship between language and thought are to a considerable degree independent of his idiosyncratic position on phenomenal consciousness. Those who will find his views on the latter topic unappealing will find a good deal to engage their interest in the rest of the book. The idea that we think and speak in the same language is an appealing one. Carruthers’ defence of it is novel and refreshing, and his arguments concerning which parts of our thinking is done in natural language are interesting in their own right. Even if Carruthers is wrong about what it takes to be conscious, he may be right about much else. The University of Liverpool Barry Dainton