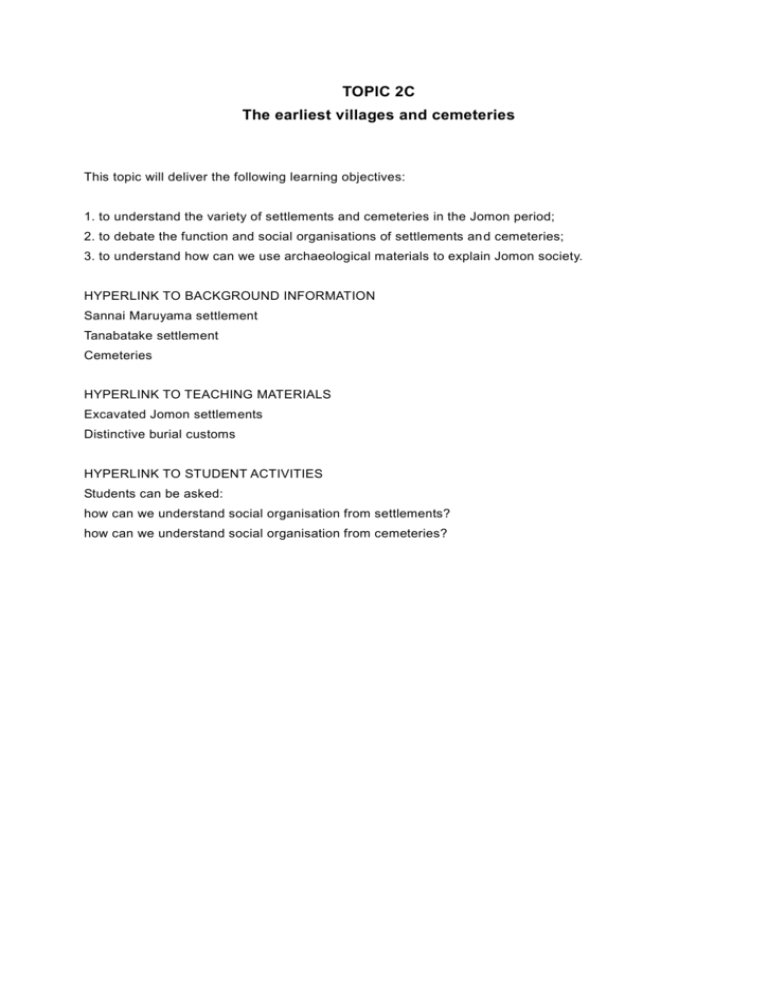

TOPIC 2C The earliest villages and cemeteries This topic will deliver

advertisement

TOPIC 2C The earliest villages and cemeteries This topic will deliver the following learning objectives: 1. to understand the variety of settlements and cemeteries in the Jomon period; 2. to debate the function and social organisations of settlements an d cemeteries; 3. to understand how can we use archaeological materials to explain Jomon society. HYPERLINK TO BACKGROUND INFORMATION Sannai Maruyama settlement Tanabatake settlement Cemeteries HYPERLINK TO TEACHING MATERIALS Excavated Jomon settlements Distinctive burial customs HYPERLINK TO STUDENT ACTIVITIES Students can be asked: how can we understand social organisation from settlements? how can we understand social organisation from cemeteries? BACKGROUND INFORMATION Sannai Maruyama settlement Excavations were conducted in 1992-1994 ahead of the construction of baseball stadium. These revealed a particularly high concentration of features and artefacts. Aomori prefecture decided to halt the construction of the stadium and to preserve the site. Af ter that, about 30 test excavations to investigate the whole structure of the site were conducted. The site was occupied from the second half of the early Jomon to the end of the middle of Jomon (approximately 1,500 years). More than 500 pit dwellings wer e identified. Most are in the stadium area, but some were identified to the south of this. Flask-shaped pits are thought to be storage facilities, because remains of sweet chestnuts or horse chestnuts have been found in the bottom of these at other sites. Some sites have post-built structures with no clear evidence of a floor. Most archaeologists assume that they had raised -floors and that they were used for food storage. Arrowheads of obsidian from Chubu region, and jadeite pendants from the border area between Niigata and Toyama prefecture were found. These show the wide trading contacts of people at the settlement. Tanabatake settlement Tanabatake was occupied from the beginning to the end of the middle of Jomon, approximately 1,000 years. Archaeologists excavated 146 pit dwellings at the site. At both of parts of the settlement, clusters of burial pits were placed between the central plaza and the pit dwellings. Cemeteries Bodies in the Jomon period were usually buried in oval or circular pits. The acid soils of Japan tend to erode bone and burials often survive better within shell middens where the calcium of the shells helps to preserve them. One particular type of burial pit (shuteibo) was set inside a circular embankment heaped up from the earth removed by digging the pit. Most shuteibo are approximately 20 metres in outer diameter, 10 metres in inner diameter. Extra large examples were discovered at Kius shuteibo -gun in Ishkari basin where some were up to 75 metres in outer diameter, and up to 5.4 metres high from the floor of the pit. The spatial structures of cemeteries were different in terms of how they reflected their social groups. many have clear segments of burials. They may have different positions inside or outside their settlements. Some segments could be of different shapes, for example, lumps at Tanabatake and linear at Sannai Maruyama. Regional diversity in spatial structure of Jomon cemeteries and changes over time would reflect differences in social organisations and relationship s among communities. It might be associated with differences in the environment or subsistence system. TEACHING MATERIALS 01 Excavated Jomon settlements Excavations in Japan are often on a large scale and whole settlements have sometimes been excavated. These can reveal a lot about the way of life of people, their attitudes and their society. The following teaching materials can be used to answer the question How can we understand social organisation from settlements? Editorial note: Figures 01 to 04 need to be shown together as part of a set, but could be downloaded separately. Figure 01 The reconstructed site of Sannai-maruyama in Aomori prefecture Figure 02 The excavations at Sannai-maruyama in Aomori prefecture Figure 03 An excavated ritual structure at Sannai-maruyama in Aomori prefecture Figure 04 Burial pits at Sannai-maruyama in Aomori prefecture Many pit houses have oval or circular shape, and are around 3 to 4 metres long (Feature 1 on Figures 01 and 02). The largest pit house is 32 metres long (Feature 2 on Figures 01 and 02). About 100 post-built structures that may have been for storing food were discovered in the centre of stadium area (Feature 3 in Figures 01 and 02). There were two rows of oval burial pits including several hundred burials on both sides of a 420 metre-long earthen pathway from the stadium area to the eastern end of the site (Feature 4 -1 in Figures 01 and 02). Another burial row was found from the south of stadium area to south -east (Feature 4-2 in Figure 01 and Figure 04). Some pit burials have circular a stone arrangement around the top. There are also approximately 800 upright buried jars, which were thought to be burials for babies or infants. The bases of six large chestnut posts, c. 1m in diameter, were discove red still in their post holes (Feature 05 in Figures 01 and 02, also Figure 03). Kobayashi Tatsuo has noted how the midwinter sun sets between the two lines of posts. There are also north and south embankments in the stadium area 2 metres high with deposits of soil, charcoal, pottery, stone tools, in use for about 800 years (Feature 6-1 and 6-2 in Figures 01 and 02). Jadeite pendants and over 2,000 dogu clay figurines indicate that these earthen mounds were used for ritual activities. Editorial note: Figures 05 to 06 need to be shown together as part of a set, but could be downloaded separately. Figure 05 Excavation of Tanabatake settlement in Nagano prefecture Figure 06 Plan of Tanabatake settlement in Nagano prefecture There are two circular zones of settlement, a north village and a south village. The pit houses in the south can be divided into two major segments, an eastern and a western group There are no clearly identified features for storage. Some scattered pits around pit dwellings might be used as storage pits, but it is possible to use the attic space of pit houses for this. There were 116 Middle Jomon pits. These may be burial pits since jadeite pendants, jars, and stone knives were discovered at the bottom of them. These would have been g rave goods. At the south village, the east and west segments of the pits seem to face each other across the central plaza. 14 rectangular post-built structures were found around the circumference of the central plaza. There were quite a few artefacts, but buildings that have a different structure from pit dwellings are thought to be facilities for ritual. The dogu clay figurine, ‘Jomon venus’ in module 3c, was found almost complete in No.500 small pit in the central open area of south village. Figure 07 Obsidian arrowheads and flakes from Tanabatake settlement in Nagano prefecture There are over 10,000 obsidian tools, pebbles and flakes, weighing approximately 110 kg from the site. Arrowheads usually weigh only 0.5g, so that 110 kg of obsidian is equal to 220,000 arrow heads. This trial calculation indicates that the amount of stocked obsidian at Tanabatake is beyond that needed for self-consumption and is for trading. This site is located 10 km away from a good obsidian source in Mt. Kirigamine. Figure 08 Excavation at Aota in Niigata prefecture The exceptional preservation conditions at this waterlogged site meant that chestnut posts survived into the present. Buildings of this type were well-suited to the damp ground conditions at Aota. Over 50 post-built structures from the Final Jomon period were found (Figure 08). They had been flooded as the river changed its course. A rare find was part of wall panel of plant material. Figure 09 Reconstruction drawing of Aota in Niigata prefecture The settlement had an earlier and a later phase. Dating by analysis the tree rings in the wood suggests that 8 or 9 buildings formed the row of houses at the same phase. Approximately 70 flask-shaped storage pits were excavated. Buried jars were found that were burials for babies or infants. No burial pits for adults were found. The only evidence for ritual was a few clay figurines and stone objects. Figure 10 Diagram of the number of houses at Sannai Maruyama The calculation of the number of houses at each phase at Sannai Maruyama is a minimum estimate, as not all the houses excavated had pottery that could be used to date them. STUDENT ACTIVITY 01 Key question How can we understand social organisation from settlements? Secondary questions What can we tell about social organisation from the spatial arrangement of features, and the nature of the features and finds? What function did settlement have? TEACHERS NOTES Understanding long and short time scales On a short time scale, we can look at the size and structure of t he village in one of its phases. Phases are defined by the succession of different types of pottery. Each phase varies between several decades and a few hundred years in length. Analysis at Tanabatake showed each phase to have 10 to 20 houses, but the phases could be long and there may have only been five houses at any one time. On a long time scale, we can see the same structure surviving throughout the life of the settlement. Settlements often had some kind of spatial arrangement. The concentric nature o f the circular villages at Tanabatake was deliberately maintained over 10 phases, nearly 1,000 years. The two groups of pit dwellings also continued, even though the boundary between them was moved over time. This duality in the structuring of settlement space is seen in many Jomon villages and probably reflects an important principle of Jomon social organisation. Multiple functions in settlements It is certain that core of the settlements, such as Sannai Maruyama and Tanabatake, were the centre of daily life with pit houses and storage facilities. They were also the centre for other social activities such as rituals, funeral ceremonies and exchanges. The concentric ring at the centre of the settlement was clearly a valuable place to the people that reflects the social unity of the community. It stands as a symbols the Jomon society. On the other hand, the fewer ritual and burial element at Aota site in the final Jomon show that it had more limited functions than the settlements in the middle Jomon. The cem etery of the people who lived in Aota might be located away from village. This spatial separation the living and the dead in different functional spaces appeared during the late Jomon. TEACHING MATERIALS 02 Distinctive burial customs Jomon people used various forms of burial. Some were placed inside their settlements, while others were is separate cemeteries. Some had grave goods, while others did not. The following teaching materials can be used to answer the question How can we understand social organisation from cemeteries? Figure 11 Plan of Kusakari kaiduka (shell midden), Chiba prefecture Several rescue excavations of a whole terrace of approximately 260,000 square metres revealed a whole circular settlement 130 metres long and 80 metres wide. Th e outer circular ring has approximately 300 pit dwellings in the middle Jomon, and at least 21 houses were reused for burials. Over 1,000 pits found outside of the central plaza are thought to be storage pits, and some are also reused for burials. Figure 12 Burial at Ubayama kaiduka (shell midden), Chiba prefecture Burial in an abandoned house (Haiokubo) is popular in the Tokyo bay area in the middle Jomon. Other good examples were found in shell middens at Ubayama and Kasori. An analysis of the size and shape of the teeth and the skulls of the skeletons was done for two burials at Kusakari and Ubayama. These showed the reuse of pit dwelling as a burial is associated with one particular family. However, both burials but were added to the disused pit house sometime later than it was adandoned. Figure 13 The site of Kius shuteibo-gun (group of burial enclosures), Chitose city This a large burial enclosure, 37 metres in outer diameter. 220 people have been arranged to show the size and height of the inner and outer edges of the bank that surrounded the pit in the middle. Such rounded-bank burial enclosures (Shuteibo or Kanjo-dori) are distinctive in Hokkaido island in the second half of the late Jomon. They are especially concentrated in Ishikari basin, south of Sapporo city. Figure 14 Excavation of Bibi 4 shuteibo-gun (group of burial enclosures), Chitose city A group of sites along the Misawa river was excavated during construction of New Chitose airport, and 16 shuteibo in total were uncovered from sites of Misawa 1, Bibi 4 and Bibi 5. Figure 15 Excavation of a burial enclosure at Misawa 1, Chotose city At Misawa 1, two burial enclosures form a pair and three such pairs were located on the edge of the river terrace of Misawa river. Skeletal remains were of adult males, adult females and children of unidentified sex. Figure 16 Plan of grave goods at Misawa 1 burial enclosure, Chitose city One of characteristic of this burial custom is the occurrence of grave goods. 70% of the burials in the JX03 enclosure had such goods. This is much higher than in other cemeteries in the Jomon period. Figure 17 Grave goods in burial 103 at Misawa 1, Chitose city Artefacts found at the bottom of burial pits were identified as grave goods. Grave goods at this site can be divided into three categories: a) ritual objects such as stone bars (sekibo) and lacquered bow and ware; b) ornaments like Jadeite beads; c) utensils, usually pottery and stone tools such as arrowheads and polished axes. One burial had categories a, b and c. Three had categories a and c. Another three had categories a and b. Five had only category c. The five remaining burials had no grave goods. In the paired enclosure of JX04, only 39% of burials. One had categories b and c. Two had either a or b. Four had only category c. Eleven had no grave goods. Figure 18 Burial pit at Tanabatake West segment in the south village Burials at Tanabatake had either ornaments or utensils. This was one of five to have jadeite pendants as ornaments. Three others had other kinds of ornament. Less than 10 burials had only utensils. Probably only 20% of burials here had grave goods. At Kusakari, there is an antler waist ornament from two burials. Others had a clay earring or a shell bracelet. Burials with ornaments were scattered through the cemetery. There was no concentration into any particular section. STUDENT ACTIVITY 02 Key question How can we understand social organisation from cemeteries? Secondary questions What do the arrangement of burials and the occurrence of grave goods tell us about the social organisation of the population? TEACHERS NOTES The spatial structure of cemeteries We can often distinguish a hierarchy in the spatial structure of Jomon cemeteries. The southern cemetery at Tanabatake consists of two clusters with dozens of burial pits. Both clusters include smaller groups: units of several burials. Different social divisions at small and large scales were reflected in the spatial division of the cemetery. Small sized groups: a unit of burials Burials in abandoned houses in the middle Jomon shell middens of Kusakari, Ubayama and Kasori are good examples of small groups. Depression-shaped circular or rounded squares show clear boundaries for burials of small groups. The results of analysis of the skeletons show th at unit corresponds to a family unit. At Tanabatake the overlapping of small units by an accumulation of burials over a long time makes it hard to identify them. At Sannai Maruyama, it seems that we can recognise some rows of pit burials. However, it was impossible to identify group composition because there were no skeletal remains surviving. At Misawa 1, units of burials are very hard to see. Middle size group: segment of burials Shuteibo (round-bank burial enclosure) is a burial that clearly shows the boundary of a segment. The skeletal remains show that a single shuteibo segment includes a number of family units. This corporate group is thought to be a descent group, such as a lineage or clan. The paired structure of some Jomon villages is reflected in their cemeteries. At Misawa and Kius, two burial enclosures formed a pair. At the south village in Tanabatake, two major spatial segments and a clear mortuary zone in the central plaza emerged over a long time. At Sannai Maruyama, two rows of burial pits were maintained over hundreds of years until the end of occupation. Both cemeteries contained a number of families. At Kusakari, the existence of segments is unclear. Clusters of burial near the dwelling zone may be accumulations of family burials Spatial positions of cemeteries There are three patterns in the positioning of cemeteries Centralised pattern. The example of the south village at Tanabatake shows efforts to integrate segments within the central plaza. This reflects the desire for the unity of the community. Adjoining pattern. Cemeteries are located next to the settlement. Sannai Maruyam and Kusakari have this pattern. Independent pattern. In the late and final Jomon, cemeteries often are set away from dwellings in an independent location. Groups of shuteibo at Misawa 1 and Kius, had no pit dwellings near them. This is the reason why few ritual remains are found at Aota village in the final Jomon. Stone circles of Oyu and Komakino (in topic 3c) are also this located away from the settlements . Differences in grave goods and social complexity At Sannai Maruyama and Kusakari, there were no clear differences between the burial rows or units of burials. At Tanabatake west in the south village, there is a predominance of grave goods. Misawa 1 JX03 burial enclosure has more, and higher quality, grave goods than JX04 burial enclosure. Differences between segments implies differences in the nature of the lineages. It is possible that these differences became more obvious in some limited regions and pe riods. Did the differences Tanabatake and Misawa 1 have the same meaning? Probably both had different meanings, although what these were has been controversial. The differences are based on different categorisations of grave goods. Misawa 1 JX03 burial enclosure has a more complicated combination of goods than Tanabatake. It also has distinctive ritual objects such as stone bars. A more complicated combination appeared within the predominant segment at JX03 and the total number of social categories increased. In other words, social complexity increased. There are many more burials with grave goods in burial enclosures than at Tanabatake in the middle Jomon, and differences between paired enclosures is also distinctive. This seems to show increasing concern for the social unity of segments and hierarchical relationships among them. There is controversy about the values of some rich grave goods, such as burials with a combination of categories a and c. Were these the leaders of an egalitarian society or an up per class within a stratified society?