Figure 2 - Basic Income Earth Network

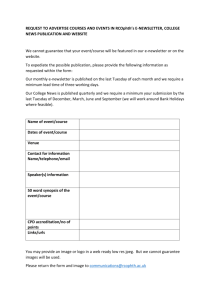

advertisement