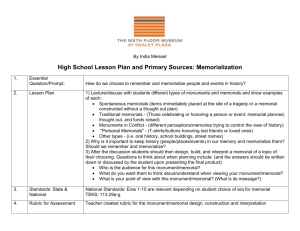

Lecture Text - The Stained Glass Museum

advertisement

HE IS NOT HERE... First World War memorial Stained Glass and the Fragile Art of Remembrance NEIL MOAT PhD 01 In this centenary year marking the start of one of the twentieth century’s bloodiest conflicts, I am going to attempt something rather presumptuous for a mere fifty-five year old • I want to convince you – if not to love – at least the better to appreciate the countless memorial stained glass windows erected throughout this country in the wake of the Great War. [I make no apology that many of my examples are taken from my native North-East] • Of course, we already know that these memorials are historically important and that some are truly beautiful, even moving works of art… • but some cautionary tales may leave the more thoughtful amongst you a little uneasy in your seats. • Indeed, there are some here tonight who might salute the artist of this scene for his unflinching honesty, and yet others who would find such reminders of the futility of war deeply disturbing and inappropriate, either as a memorial or in its church setting [Michael Healey (1873-1941) of the Dublin-based cooperative An Túr Gloine (The Tower of Glass) for St. Peter’s (C-of-E), Wallsend (Tyne & Wear), 1922]. • Our duty rather, as good art-historians, should be to ask searching questions of these memorials, and rather than interpose our own reflections and concerns, to try, as dispassionately as we might, to understand the function and meaning of these windows… • and therein lies the chief problem with my subject tonight. 02 A great deal has been written on the origins and monuments of the War Memorial Movement, and predominantly on the great civic and public war memorials – • However, it is worth noting that such memorials were far from being typical of the post- war drive to commemorate the fallen. • Firstly, they were raised in perpetuity; permanence was ensured by the use of costly materials; granite, Portland stone, marble and bronze – the Leicester Arch of Remembrance (now Grade-I listed), was executed in Portland stone at a cost well in excess of £25,000; even so, the original concept had to be significantly revised as sufficient funds could not be raised in time [the architect Edwin Lutyens here rings the changes on themes first explored in the Thiepval Arch and Whitehall cenotaph]. • Secondly, political and religious references were either wholly suppressed, or tacitly assumed rather than overtly displayed, the better that such memorials could represent the 1 whole community, of whatever political persuasion or faith, or none – the Leicester memorial alone commemorates twelve thousand fallen drawn from the city and the surrounding county. • Patriotism and the cult of memory thus became the only virtues such monuments could ordinarily uphold if they were to garner wider public support for their erection. 03 The stained glass memorial was very different. • For a start, stained glass was much the more affordable – in the order of hundreds of pounds as against the thousands and tens of thousands for the great civic memorials. • Even so, the fragility of the medium seems almost counter-intuitive to its commemorative purpose – and as you can see, this window has taken some knocks. • The context for such memorials was often – although not invariably – religious, and reflected the concerns of the individual congregations, institutions, prominent patrons or families who commissioned them, rather than the wider community. • Constraints over content were therefore much less severe than for the major civic memorials; indeed, the formal inventiveness and variety of imagery to be found in war memorial stained glass is truly astounding. • This ‘jazzy’ window was designed in 1921 by the Irishman Hubert McGoldrick (1897- 1967), of the An Túr Gloine cooperative, for St. Paul’s (C-of-E) church, Askew Road (Low Team), Gateshead. • It depicts four of the orthodox Christian martial saints (i.e. Martin, George, Michael and Paul the apostle), but otherwise makes no overt reference to the war – that function was taken by the chapel in which the window was placed, dedicated to the fallen of the parish. • I got to know this window some thirty years ago, just as the church was set to close. The window was saved when the church was demolished, but subsequently sold into private hands – the image is a montage of photos taken when the window was under assessment at York Glazier’s Trust. • As this was McGoldrick’s only window on the British mainland, you might think it shameful that it should have been lost to public view – surely this could not happen today. 04 Churches continue to be threatened daily with closure – in this case All Saint’s (C-of-E), Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, a late work (1910-13) by the architect Gerald Callcott Horsley (1862-1917). • At the base of the large memorial east window, by the prolific Dundee-born artist James Eadie-Reid (1868-1928), a soldier and sailor, as representatives of the armed forces, enter into the presence of the enthroned Christ, there to receive crowns of victory, ushered in by the four Evangelists acting as psychopomps. • But that is not all… • You will notice along the base the top of a large triptych reredos placed on the High altar, also painted by Eadie-Reid as part of the parish war memorial. The triptych depicts members 2 of the armed forces as witnesses of Christ’s passion, who are thus enlisted perpetually in the liturgy of the Mass. • The memorial is therefore a larger thing than just the window; triptych and window speak to each other. Indeed, we might save the church; we might even save the window and the reredos as separate art-works, but having been bound into the life of the worshipping community, the combined function of window and triptych will be forever lost, if and when the church closes. 05 The rate of closures amongst Nonconformist denominations is even higher than for Anglicans and Roman Catholics, and the losses are commensurately greater, even though congregations frequently make heroic efforts, when they abandon their former places of worship, to find new homes for memorials, or to trace surviving relatives or descendents. • I was alerted to this window – made by the London studio of Arthur J. Dix (1861-1917) – by the historian Andrew Tatham, who was researching memorials to individual members of the 8th Royal Berkshires, preparatory to an exhibition at the Flanders Field Museum at Ypres (Belgium) in September next year. • The memorial to William George Hobbs (d. 1915) had gone ‘missing’ when Richmond Green United Reformed Church (formerly Presbyterian) was sold for conversion into flats, but had been photographed in situ by English heritage shortly before closure. 06 I recognised it has having gone through the ‘Trade’ some years ago, and was able to put Andrew Tatham in touch with the vendor. • However, the window illustrates a further difficulty with this genre of stained glass – • The young Lieutenant Hobbs, by trade a solicitor, is pictured patriotically at the far left as St. George (Amor Patria), paired with Fortitude and Wisdom on the right, as witness to Christ’s Second Coming. The chosen text – from Matthew’s Gospel, (Chap.25.34), Come ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world – would seem to imply that the young man’s death in action was somehow the making of him and duly ordained… • Sentiments indeed not that far from those of Rupert Brooke, in a letter of 1914 to his fellow poet John Drinkwater: • ‘Not a bad place to die, Belgium, 1915[eh?]. I want to kill my Prussian first. Better than coughing out a civilian soul amid bed-clothes and disinfectant and gulping medicines in 1950. The world’ll be tame enough after the war, for those that see it... Come and die. It’ll be great fun...’ 07 Nor were such thoughts an imposition by the living on the dead, as is so often presumed… 3 • The Newcastle-born artist Victor Noble Rainbird (1888-1936) was a prizeman of the Royal College of Art under Professors Lethaby and Moira, and of the Royal Academy Schools, but saw active service with the Northumberland Fusiliers in France. • Even so, his post-war designs for stained glass – almost wholly for Nonconformist (mostly Methodist) congregations – seems to tap into the same sentimental vein – of battlefield visions of the Risen Christ and His angels – as regular stay-at-home propagandists. • Indeed, Reed, Millican & Co. – hitherto a Newcastle-based commercial glaziers – felt justified in entering the burgeoning post-war market in memorial stained glass solely on the strengths of Rainbird’s designs for them. • However, the ongoing closure of chapels has meant that almost all of Rainbird’s war memorial glass has been lost [two examples known to survive are at Allendale (Northumberland) and Papa Stour (Shetland)]. • [I was lucky enough many years ago to see the executed version of the design on the left, dated 1919, for the Thomson Memorial Hall, Sunderland; the location of the designs on the right (from my own collection) have yet to be traced]. • Our embarrassment at such imagery – combined with the relative inaccessibility of the windows, mostly locked away in churches and chapels – may well account for the general lack of interest shown by art-historians in the genre. • And yet, numerically speaking, stained glass is far and away more truly representative of the War Memorial movement, than are the more studied public and civic monuments. • We need therefore to put our embarrassment – and any latent prejudices – to one side, and seriously grapple with the meaning and function of art such as this. 08 And so to return to my earlier observation; why commemorate the fallen in so fragile a medium as stained glass? And the answer is of course that there was an already existing tradition. • Although the notion of erecting memorial windows was a medieval invention, its revival during the 19thC as a more affordable means for raising a monument became the chief means of patronage for new stained glass, as indeed it still remains so today. • Moreover, the quality end of the market was increasingly seen as a legitimate medium in which high-class artists might work, or make entirely their careers and reputation. • Thus, the notion of raising a fine memorial window, designed and/or executed by a leading contemporary artist, had become perfectly natural by the close of the 19thC. • Specifically military and regimental memorials in stained glass appeared relatively early on during the revival, although – save for the regimental insignia and battle honours, or the martial subject matter – these were barely distinguishable from other memorials… 4 • [left] detail (St. Michael) of window to Officers, non-Commissioned Officers and Men of the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers who perished during the Indian Mutiny of 1857-9, erected 1861 in St. Nicholas’ church, Newcastle upon Tyne (now the Anglican cathedral). • Made by Wm. Wailes’ manufactory (Newcastle); Wailes repeated the design virtually verbatim, but without the military insignia, a few years later at Hereford cathedral (to be seen in the north transept chapel), and further non-military versions can also be seen at Barton-leStreet, Barnard Castle and Sedbergh parish churches. • If the regimental memorial window lacked specificity as a genre, it was nevertheless an important precursor of later developments, being raised to the collective memory of both officers and men who were, more often than not, buried where they had fallen in a foreign land. • Thus the pattern established by Wailes at Newcastle cathedral was continued, with little deviation, in the regimental memorials to the fallen of the South African campaign (1900-02) and finally [right] the Fifth Northumberland’s commemoration of the 1914-18 war, erected in 1921 and made by the London studio of Percy Bacon & Bros. 09 Even so, the figures of Joshua, the young shepherd-boy David – ready to fell the giant Goliath with a single sling-shot – and the archangelic ‘captain of the Lord’s host’ (St. Michael), are perhaps testament to the manly ideals of the officer class and of the English public school system, than of the ordinary soldier. 10 And the same might be said of a large number of war memorials raised by members of the aristocracy and landed gentry, as in the Arthurian theme (Sir Galahad and Sir Bors) of this window at St. Cuthbert’s church (C-of-E), Holme Lacey (Herefordshire) • There is nevertheless a poignant irony here, in that the Australian-born brewing magnate Sir Robert Lucas-Tooth only purchased the Holme Lacy estate in 1909 – • the window insinuates itself into the former mausoleum church of the Scudamore family by affecting the aristocratic ideals of chivalry, an attempt at continuity sadly purely illusory, as all three of Sir Arthur’s sons were killed during the 1914-18 War. 11 Complaint is often made of such memorials, that the endless depictions of armoured knights and warrior angels are somehow a denial of reality – I know because I once complained as much myself. • But the truth is that artists in stained glass were faced with a particular difficulty not encountered in the more abstract media of stone and bronze – the banality of the modern military uniform. Indeed, what can be done with a figure dressed in what amounts to khaki coloured tubing? • In this window of 1930-31, the joint artists, George Washington Jack (1855-1931) and Edward Woore (1880-1960), attempted to distract our attention from the ‘effigies’ in khaki by 5 the introduction of large blocks of complimentary colours, blue, tangerine and pink – perhaps none too successfully. • And even for artists working after the Second World War, as the late Stanley Murray Scott FMGP (1912-1997) related to me in November 1993: • ‘Winged angels have probably not disappeared from the repertoire even now – they offer such scope for colour and pattern and sweeping lines! Never discount the practical creative aspect!’ 12 Of course, the narrative of self-sacrifice embodied in many war memorial windows avoided comment on the ‘reality’ of compulsory military service, ill discipline in the ranks, the conduct of the war effort itself, or indeed any criticism of the social or political order that brought about the conflict. • This is often held against the genre – but how could it have been otherwise. For the sake of the living, some justification had to be found for the terrible slaughter… • The window we have just seen was installed in the large suburban church (C-of-E) of St. James and St. Basil, Fenham (Newcastle upon Tyne). The entire building, parish hall, vicarage and memorial garden were the gift of the retired Tyneside shipping magnate, Sir James Knott (1855-1934), who had lost two of his three sons in the 1914-18 war (Major James Leadbitter Knott and Capt. Henry Basil Knott). • Despite the memorial nature of the gift, the church is a remarkably jolly life-affirming Arts and Crafts masterpiece, begun in 1928 and dedicated in 1932. • The actual memorial window was hidden away discretely in a side chapel. It seems to suggest that the young officer’s defence of the dispossessed was rooted in the values of honour and fair play learnt at school (Eton College in this instance); the privations and terrors they endured on the Front were for the preservation of life and liberty at home (here Close House, the Knott’s country retreat outside of Newcastle). Few at the time would dissent from upholding such honourable virtues… 13 If in Britain the memorial window was a thoroughly established genre, be it for individuals or for whole regiments of men, the collective commemoration of so many ordinary citizen-soldiers was something altogether new. • And for inspiration British artists had to look further afield, to countries and traditions where the notion was already well established. France was the obvious choice as the closest to home, less so the United States; countries where the ideal of the citizen bearing arms in defence of the democratic nation-state had long been fostered in the wake of Revolution. • In particular, the catastrophe of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 helped crystallise a particular set of images – centred on the volunteer foot soldier cast as universal tragic hero – that were to prove immensely useful to stained glass artists in Britain… • It is perhaps worth digressing a little to follow the development of such imagery. 6 • The life-size bronze Gloria Victis by Antonin Mercié (1845-1916), shown to great acclaim at the Paris Salon of 1874, was amongst the first major artworks to capture the public mood of the Third Republic, and the widespread sense of outrage and shame in the aftermath of the French defeat. • The fallen warrior – his sword broken but still firmly held – is carried off by a winged figure of Victory. Gloria Victis – ‘Victory for the Vanquished’. The allusion to Classical Greek and Renaissance sculptures renders the contemporary historical as both timeless and universal. The citizen’s sacrifice was not in vain; the shedding of their blood will yet bring peace with honour, reinforced by the Christological pose of the warrior as a modern martyr – an allusion constantly reworked by later artists. • Mercié’s bronze proved tremendously popular [left – the original at the Petit Palais]; town councils queued up to raise copies as memorials to their war dead, and it was reproduced endlessly in studio reductions for the art-loving home [right]. 14 Mercié followed this in 1882 with another notable Salon success, his Quand même!, (‘Even So!’), which brought the patriotic theme of his Gloria Victis right up to date., • It depicts a girl in Alsatian dress snatching the rifle from a dying volunteer. The latter again adopts the pose of the fallen martyr, whilst she clearly alludes to the figure of Marianne as the embodiment of Republican France. • The bronze version, Aux défenseurs de Belfort, was duly installed in August 1884 on the principal town square of Belfort, which having heroically withstood a 103 day siege until the armistice of January 1871, remained the only bit of Alsace not ceded to Germany under the treaty of Frankfurt. • As such, the statue became notorious for its precocious articulation of a burgeoning right- wing ultra-nationalist faction in French politics – what became known as Revanchism. 15 By the turn of the century, Revanchist politicians and sympathisers were eagerly promoting the commemoration of France’s war dead of some thirty years earlier – both as a means for stoking anti-German feeling – and to agitate for the return of lost French territory. • A spate of monuments thus sprang up across northern France or in German-occupied Alsace-Lorraine. • Their unveiling would often prove notably hot-tempered events. • Thus the German authorities became seriously alarmed by Emmanuel Hannaux’s (1855- 1934) monument at Noisseville [left] – Aux soldats français tombés glorieusement au champ d’honneur – unveiled in 1908 to a highly emotional crowd numbering over a hundred thousand. • The placing of the monument was equally incendiary, on high ground overlooking and dominating the German monument at Retonfey – the latter erected by the Prussian First Army Corps to mark the grave of their comrades killed during the Siege of Metz [right]. 7 16 Even so, Hannaux’s monument simply recycled themes already rehearsed by Mercié and others; here, the heroic figure of the poilu or volunteer infantryman – already stock-in-trade for such monuments – falls, clutching his heart, into the arms of a grateful France. 17 The longevity of this rather unsavoury ultra-nationalist imagery is indeed surprising. Replace the figure of France with an angel or angels, or even the Crucified or Risen Christ Himself, and we have the germ for so many later monuments aux morts, as the communal memorials to the fallen of the First World War are known in France… • whether in stained glass or as here in bronze [left], by the noted sculptor Robert Delandre (1879-1961), erected in 1922 at Barentin (upper Normandy). • British artists, although seemingly well aware of this long-established French tradition – through either sketching trips or contemporary art periodicals – seem to have fought shy in adapting its formal language for public war memorials at home. • Ferdinand Victor Blundstone’s (1882-1951) bronze memorial (1922), for the central courtyard of the London Prudential Assurance building, offers a rare – and I think startlingly successful – instance of a British memorial in the public sphere that is clearly indebted to recent French examples. • Yet even here, one can perhaps see how difficult it was not to appear distressingly jingoistic or triumphalist in the immediately post-war context… 18 Once the European conflict had morphed into a prolonged period of bloody attrition, the scale of the post-war task of commemoration became all too readily apparent. And so far as the British arts establishment was concerned, the omens were not good… • In 1915, Lawrence Weaver (1876-1903) – then architectural editor of Country Life magazine – brought out Memorials & Monuments in an effort to mould the public taste. • As he wrote in the Preface: • ‘After the war in South Africa hundreds of monuments of all kinds were set up, in thankful remembrance of those who there gave up their lives… [However] the result[s] revealed the exceeding poverty of memorial design in Great Britain. It is clear that the artistic ability of the men who build and adorn our churches is not employed as it should be on the memorials which they so often contain… The purpose of this book is not so much to provide a historical account of the development of those types of memorials which are the most suitable for the present use, as to focus attention on good examples, old and new… After the return of peace there will scarcely be a church, or chapel, or school, or village hall… which will lack records of those ‘who held not their lives dear’, whether they laid them down or returned safe to their homes… The book is published in the hope that it may be useful to people who are considering memorials and that it may lead them to the artist rather than to the trader’. 8 • Weaver’s publication, with its helpful hints on materials, style and even the choice of appropriate texts, proved to be immensely influential, yet he was curiously silent on two fronts. Weaver entirely passed over recent sculptural developments in France – for perhaps understandable reasons – and he failed to accord at all a place for stained glass. • Further efforts to spur the public taste followed in the summer of 1919… • The Victoria & Albert Museum mounted an historical survey of war memorials, to be followed by an exhibition of recent war memorial designs at the Royal Academy of Arts. Again, the recent French experience was conspicuously overlooked. The latter exhibition, on the other hand, displayed a pronounced bias in favour of the fine artist at the expense of the larger commercial studios and manufacturers, and included a significant showing by stained glass artists, many of whom we would now classify as in the Arts and Crafts camp. • The Academy also hosted concurrently with these exhibitions a national ‘Conference on War Memorials’, from which sprang the notion of arts advisory committees, as later set up by a number of Anglican dioceses, in an attempt to exert some measure of ‘quality control’ over memorial designs [a system still with us and now fully institutionalised]. 19 Given this background, it is all the more surprising how responsive were British stained glass artists to the more reactionary strand in recent French monumental sculpture. • Quite why this was so is difficult to understand; it would certainly be worth further investigation. • In place of the traditional French figure of the wounded or dying poilu, we find the British ‘Tommy’, usually to the exclusion of all other armed forces, as was so often the case in France [reinforcing the popular view of the conflict as one solely of trench warfare]. • Perhaps the most notorious example was created by the artist James Clark (1858-1943), whose painting, variously titled Duty or The Great Sacrifice (exhibited 1914), tapped into a national mood that gave credence to battlefield visions of Christ and His angels, or even of Arthurian knights. Clark’s painting proved tremendously popular, often reproduced in magazines, posters and in stained glass… • as here, the memorial to 2nd Lieut. John Miles Moss (d. Sept. 1915) for the north transept of St. John’s church (C-of-E), Windermere (Cumbria), and executed by Clark’s preferred glaziers, the London studio of Arthur J. Dix, [church now closed and most of its glass dispersed]. • So famous and almost talismanic was Clark’s painting, that the illusion of a framed image is maintained almost in defiance of the tripartite window openings, rather than filling the available space… • On a more positive note, the artist shows us how flags should properly be handled in stained glass, by breaking up their visually discordant geometric patterning... 9 • Clark subsequently donated his painting in 1915 to a Red Cross War Relief exhibition at the Royal Academy, where it was bought by Queen Mary [it now hangs in the Battenberg memorial chapel at St. Mildred’s church, Whippingham, Isle of Wight]. 20 An even more startling essay on Clark’s theme of sacrificial heroism is this window of 1919, designed by his fellow Hartlepool-born colleague Philip Bennison (1890-1924), as the parish memorial for the medieval village church of St. Mary Magdalene (C-of-E), Hart, on the rural outskirts of Hartlepool. • Bennison trained as an artist successively at Hartlepool, Sunderland and Newcastle Schools of Art, followed by two years study at the Royal College of Art, where he gained his diploma in 1916. • Excused from military service due to a debilitating lung condition – which would eventually kill him in 1924 aged only 34 – he took a temporary position as an art master at the local grammar school until July 1919, before embarking on a career as a free-lance artist. • The handful of his designs in stained glass were almost wholly for war memorials, and each makes (or made, as some have been lost) a highly distinctive and original contribution to the genre. • The best of these is undoubtedly the window for Hart, which I think a quite remarkable design, owing not a little to the work of Robert Anning Bell (1863-1933) in its claustrophobic compositional cut-offs and decorative use of lettering and insignia. • Its merits as a work of art aside, the window does nevertheless make a daring reinterpretation of Christian death, not as the prelude to a looked for resurrection, but as a kind of imminent transfiguration… 21 Underlined by pairing the hill of Golgotha, in the left hand light, with the visionary Transfiguration of Christ above… 22 Whilst in the right hand light, before the shattered skyline of a town in Flanders, young and old alike gratefully acknowledge the sacrifices made on their behalf... 23 Directly above, the stock figure of a British ‘Tommy’ heroically expires, broken and alone on the battlefield, his soul rising aloft and transfigured in a vision of beautiful youth. It is a tremendous – if somewhat disturbing – image. • But it also speaks volumes for just how deeply engrained in the popular psyche was the ‘Tommy’ as a universal figure, even for a port town such as the Hartlepools. 24 Bennison would subsequently transform this image into the bronze figure of Triumphant Youth – unveiled in December 1921 on Hartlepool’s ancient headland as part of the town’s war memorial – and symbolising (in the words of the dedication address) ‘the spiritual freedom and regeneration which comes through pain and sacrifice’. 10 • The memorial is unusual both in commemorating not only those members of the armed forces and mercantile marine who gave their lives during the war, but also the civilians – 52 men, women and children – killed during the infamous Gernam naval bombardment of Hartlepool (16th Dec. 1914), Whitby and Scarborough. • The involvement of respected and talented local artists and art masters – such as Philip Bennison [Hartlepool], Harold Rhodes (1888–) [York and Bradford], Philip W. Coles (18841964) [Hastings], Gordon Forsyth (1879-1952) [Staffordshire Potteries] – as the semi-official artistic conscience for a particular locality is quite a widespread phenomenon amongst Britain’s war memorials, and especially so in stained glass. • The artists concerned need not have been native-born to that district, but having made their reputation there, they were perhaps thought as peculiarly responsive to local concerns and of being able to produce something both modern, original and yet accessible (and certainly more affordable than established metropolitan artists). • Frequently, an academic connection or background conferred on them an authority, as regional ‘arbiters of taste’, out of all proportion to their actual artistic production. 25 Such was the case with Richard George Hatton (1865-1926), whom Bennison would surely have met during his studies at Newcastle, where Hatton was principal of the School of Art at Armstrong College (from 1911 King Edward VII School of Art, and now the School of Fine Arts at Newcastle University). • Richard Hatton hailed from Birmingham, where he studied and trained as an assistant teacher at the city’s Municipal School of Art under its influential headmaster Edward Richard Taylor (1838-1911) [headmaster 1877-1903]. • By July 1890, Hatton had been appointed second art master at Newcastle’s independent school of art. He succeeded as its principal in 1895, tasked with overseeing the school’s amalgamation with Armstrong College along with the adoption of Arts and Crafts teaching on the lines pioneered at the Birmingham School. • Despite this strong Arts and Crafts background, stained glass was not taught at the Newcastle school, although many of Hatton’s pupils did go on to work in stained glass, and Hatton himself took a keen interest in the medium. • His only surviving church window is the striking war memorial east window for St. James’ church (C-of-E), Shilbottle (near Alnwick, Northumberland), whose design occupied Hatton between 1919 and 1921. • As with the Eadie-Reid window we saw earlier at Hanley, Hatton’s Shilbottle window forms part of a larger memorial, the names of the fallen being inscribed on oak panelling around the chancel [also designed by Hatton and intended to be executed by his pupils in the art school]… 11 • the window itself universalises the parish’s loss as examples of true discipleship – following the pattern of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection – and as part of the ongoing worshipping life of this village church. 26 For many artists after the war, memorials became a staple means of business, and Hatton’s influence as a teacher informed many of these across the North-East… • [left] a champlevé enamel plaque by Hatton’s pupil and teaching colleague René Bowman [6th Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers memorial, Haymarket, Newcastle]. • [right] illuminated Book of Remembrance by Elizabeth Davies, another of Hatton’s pupils, who made a considerable regional reputation as an independent artist-craftswoman [St. Thomas’ parish (C-of-E) church, Stockton-on-Tees]. 27 It is perhaps tempting to locate such work as an example of English Arts and Crafts parochialism. But Hatton and his pupils had wider horizons than ‘England’s green and pleasant land’… • As is clear from this roughly contemporary altarpiece by the Newcastle-based artist Thomas William Pattison (1894-1983), its contrived formalism echoing not only the work of Stanley Spenser (1891-1959) and Mark Gertler (1891-1939), but also of the late Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898) – whose work Pattison specifically studied whilst in France – and Puvis’ followers amongst French post-war sculptors and painters [note the oppositions reds against blues; open versus closed gestures; turning into or turning out of the picture plane]. 28 Whilst Hatton’s design is clearly indebted to the work of his contemporary Robert Anning Bell (1863-1933), the formalism of the Shilbottle window nevertheless echoes that of Pattison’s altarpiece; e.g. the similarly stylised colour scheme and gestures; static contemplation versus emotive recognition. • Hatton also chose the calligraphic style of line-work, without shading, as a coloured sketch design in the artist’s hand makes clear; thereby breaking with the traditional, more painterly English fashion, as usually employed by Messrs. Reed, Millican & Co. • According to Hatton himself, this severely linear style derived from his examination of early medieval windows, but it could also be seen in contemporary Dutch, French and American avant-garde designs in stained glass. • The richly varied blues and gold-pinks also suggest that the window was an expensive job, although the costs were borne by the owners of the Shilbottle colliery [note the Norman slabs used ‘neat’ like jewels, a feature also seen in windows by Hatton’s younger Birmingham colleague, Richard John Stubbington (1885-1966)]. 29 Although Hatton himself did so little stained glass, his interest in the medium nonetheless had far-reaching effect… 12 • As Secretary to the Bishop of Newcastle’s arts advisory committee on war memorials, Hatton was in a signal position to influence for the better many of the commemorative projects across the county of Northumberland. • And for some parishes, the need to accord adequate tribute to their war dead was little short of heroic. • For the relatively impoverished parish of St. Augustin (C-of-E), Tynemouth, fundraising began in earnest in 1919 for what they hoped would be ‘one of the finest [memorial windows] in the North of England’; even so, it was not until 1927 that the final part of Martin Travers’ masterpiece was installed [the oculus Christ in Majesty]. • That the parish were not tempted to cut corners can certainly be attributed to Hatton’s encouragement, and I think you will agree that the results justified their perseverance [the design for the centre-light (1922) won a Grand Prix at the 1925 Paris International Exhibition (of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts)]. • At first sight Travers’ design may not appear especially topical – aside from the minute figures of the soldier and sailor – until one reflects on the Apocalyptic associations of the figure of Our Lady as Queen of Heaven, the symbolism of which, largely derives from Revelations (Chap. 12): 30 ‘And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars... and the dragon stood before the woman which was to be delivered, for to devour her child as soon as it was born... and her child was caught up unto God, and to his throne... And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon....’ • [The pairs of militant and pastoral saints, Augustin and George, Oswald and Nicholas, geographically locate the parish itself – as in the diocese of Newcastle and the English county of Northumberland – whilst also offering in George and Nicholas patrons for the army and navy combatants]. 31 Some parishes indeed went to considerable lengths to secure the best artistic effect for their memorials. • On 20 March 1922, three memorial windows were dedicated together in the north wall of St. Peter’s church (C-of-E), Wallsend, by the Dublin-based An Túr Gloine artists Michael Healey (1873-1941) and Ethel Rhind (1879-1952), • However, only the left-hand pair of windows (by Healey) properly forms the parish memorial – an oak tablet with the names of the fallen being placed between the windows.1 32 The window on the far right (by Rhind) replaced an already existing window erected by the Stephenson family but with the former dedication augmented with the names of Mrs. 1 The cost for the pair of parochial memorial windows and tablet was estimated at £650.00. 13 Stephenson’s children lost in the war [the original window was by Messrs. Baguley & Son of Newcastle; its tracery lights survive]. 33 The resulting balanced arrangement of windows is akin to a painted triptych, with the wings – the Angel of the Resurrection with St. George and St. Christopher; The Good Shepherd with Mary of Bethany and David – flanking the central more pictorial scene of Christ walking on the Sea of Galilee. • Hatton is on record as having been enthusiastically in their favour, although it surely helped sway matters that the Irish rector of Wallsend, Canon Charles Edward Osborne, was also brother to the artist Walter Osborne (1859-1903), the late cousin, friend and colleague of Sarah Purser (1848-1943), the director of the An Túr Gloine studio. 34 At the sister parish of St. Luke’s (C-of-E), Hatton publicly defended the choice of the uncompromising Wilhelmina Geddes (1887-1955) as artist for their memorial window. Of this truly monumental Crucifixion, Hatton wrote that: • ‘...it is so sincere and devout in conception as to do, what stained glass windows so seldom do, to affect the beholder. It provokes him to worship, and makes the church a shrine... It will of course be objected by some people that the window assumes too dominating a place in the edifice, and we must expect that there will be irreconcilable conflict between those who gladly permit a vigorous artistic expression in such a case to make its statement, and those who on the other hand advocate the quiet peace of unassertive, even if expressionless, decoration. For my own part I shall feel that at Wallsend there is always something not only worth going to see, but which enriches one in seeing it. The erection of so good a window makes one think of the many bad ones which lumber our churches and make them hideous...’ • Even so, the dedication ceremonies for this masterly window reveal quite a lot about contemporary attitudes to war memorial windows… • The window was unveiled on Friday 14 July 1922, in the presence of the mayor (Alderman J. Mullen), Sir George Hunter (Chairman of the neighbouring shipyards) and Bishop Taylor Smith (Chaplain General of His Majesty’s Armed Forces). Lady Hunter unveiled both the window and a bronze memorial tablet affixed to a pier in the church’s nave, but it was at the latter where ‘Reveille’ and ‘The Last Post’ were sounded, where laurel wreaths were laid and from where the names of the fallen were read out aloud.2 • This apparent dislocation between the ‘locus of memory’– placed amongst the living – and the commemorative artwork – as idealised other – is surprisingly common and needs to be borne in mind whenever consideration is given to preserving or relocating war memorial stained glass, even within the same building. 2 The cost of the window plus memorial tablet was estimated at £800.00 14 35 The Mayor and Corporation also attended morning service on the following Sunday [Geddes’ window was for a while co-opted as the town’s memorial, as the actual memorial – commissioned from the Chelsea-based sculptor Newberry Abbot Trent (1885-1953) was delayed; unveiled 11November 1925, at an estimated cost of over £1200]. • However, that evening, the scholars and teachers of the Sunday school dedicated their own, much smaller memorial window in the south aisle – • thus were the young inducted into the new cult of memory, but away from the tears of their elders. 36 More surprisingly, none of the local newspapers offered an interpretation of Geddes’ Crucifixion as a war memorial; perhaps its raw, visceral power and dominating presence, at twenty-four feet high – the principal figures therefore being well-over life-size – were thought affective enough. Nevertheless, the programme was one of extraordinary subtlety. • It was the late Dr. Tony Halliday who pointed out to me the similarities between the face of the crucified Christ and the gold burial masks of ancient Mycenae, as if Geddes were deploying an elaborate visual pun. • The face of the dead king, on whom eternal life was conferred through the laying on of the sun god’s gold, is transfigured into the face of the dying-yet-living Son of God. 37 Also included amongst the principal mourners is Joseph of Arimathea [far left], he who in legend is said to have brought the grail and even Christ himself to this ‘green and pleasant land’ – a neat and understated patriotic reference. 38 The mourners avert their gaze from the terrifying spectacle overhead, save for the centurion Longinus [far right]; as representative of the armed forces, he alone turns to look up and understand. 39 Directly above, it is the first Easter morning and the Holy Women come to the Sepulchre, to be met by a pair of angels, who rush forward crying ‘He is not here…’ Luke’s Gospel (Chap.24.6). • Geddes feeling for design here is remarkable. Note how the women seem rooted to the spot, their robes almost merging with the stones; the angels themselves form an unstable arrangement of triangles, ready to tip forward; how the gestures for each pair of figures mirror each other, the women’s clasping their vessels, the angel’s open and demonstrative. How the haloes, wings and arms of the angels form a series of interlocking circles surging upwards into the scene above, where Christ sits enthroned with His disciples at the end of Time. 40 ‘He is not here…’ For many of the families in the congregation at St Luke’s church on that July morning in 1922, those words would have resonated deeply and painfully, because of course their loved ones were not there, but here… at the Tyne Cot cemetery (Belgium) – 15 which was nearing completion at this time – and many another Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery. • The War Memorial Movement answered a profound need, since official policy impeded the repatriation of the fallen, and so, for so many families, there was no body over which to mourn, no place of grieving. • Our view of later conflicts, and official policy towards the repatriation of deceased combatants, would significantly change, but at the time, the War Memorial Movement offered the means for an unparalleled national outpouring of grief. • However, what so many war memorial windows would seem to suggest is that the public cult of memory was not enough, no matter how monumental and permanent the great civic memorials. Placed in churches and chapels, schools and hospitals, so much of this stained glass yearns for, indeed insists on, an assurance over and beyond the mere act of remembrance, or indeed the fragility of the medium… 41 And it is for this that we should study and cherish this art – as much for its painful beauty as a window on our own fragile humanity. NEIL MOAT May 2014 [Given on behalf of the friends of Ely Stained Glass Museum, at Ely cathedral, evening 24 September 2014]. 16