Pulmonary

advertisement

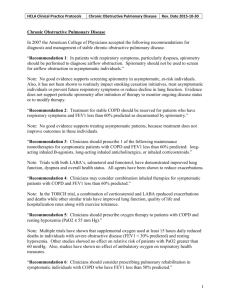

a. Objectives: i. ii. iii. iv. v. vi. vii. viii. ix. x. List typical symptoms associated with COPD Differentiate restrictive vs. obstructive lung disorders Describe the typical CXR findings for COPD patients Describe the spirometry findings of restrictive lung disease Describe the spirometry findings of obstructive lung disease Describe the factors associated with COPD prognosis Describe the difference between Asthma and COPD Describe the pathophysiology of Alpha1Antitrypsin deficiency and Emphysema Describe the most common medications used of Asthma and COPD Describe the diagnosis and treatment of Acute exacerbation of COPD USC Case # 5: COPD Mrs. Elsie Melianos is a patient who is new to Rich Creek, where you are working as a student with Dr. Brachenrich. Dr. Brachenrich says that it would be a huge help if you could go in first and find out why Mrs.Melianos is here and do a basic History and Physical. Before entering the examination room, you look over Mrs. Melianos’ new chart: Age: 59 y.o. CC: Shortness of breath Vital signs: T = 98.9, P = 82 bpm, R = 20 per min, BP = 138/75 Before entering the room, you think about Mrs. Melianos’ chief complaint: Shortness of breath. Develop a general differential diagnosis for shortness of breath. The majority of etiologies of dyspnea fall into the categories of pulmonary etiology, cardiac etiology, or a combination of the two. Other noncardiopulmonary causes are less common. Pulmonary Obstructive Lung Disorders o Asthma COPD Upper Airway Obstruction Restrictive Lung Disorders o Intrinsic Pulmonary Pathology Interstitial fibrosis Pneumoconiosis Granulomatous disease Collagen Vascular disease o Extrapulmonary causes Obesity Spine or chest wall deformities Pneumonia Pneumothorax Pulmonary Embolism Aspiration ARDS Hereditary Lung Disorders o o Cardiac Myocardial ischemia o Recent or prior CHF o Right, Left, or Biventricular Coronary Artery Disease Valvular dysfunction Left Ventricular Hypertrophy Aysmmetric Septal Hypertrophy Pericarditis Arrhythmia Cardiac Tamponade Noncardiopulmonary Metabolic o Acidosis Hematologic o Anemia Psychiatric o Anxiety o Panic disorders o Hyperventilation Pain Neuromuscular disorders o MS o Muscular Dystrophy Otorhinolaryngeal disorders o Nasal obstruction (polyps, septal deviation) o Enlarged tonsils o Supraglottic/subglottic airway stricture You enter the examination room and see Mrs. Melianos sitting in a chair reading one of the office magazines. You introduce yourself and then ask her, “What brings you in to the office today?” Mrs. Melianos responds, “Well, I’ve been having a lot of shortness of breath recently. My son is getting concerned and said that I should go see a doctor about it.” You have already developed a broad differential diagnosis for Mrs. Melianos’ reported shortness of breath. What questions might you ask her to help you narrow down the differential? You will want to obtain a better understanding of Mrs. Melianos’ dyspnea. Some questions to this point include: (you would use shortness of breath because Mrs. Melianos doesn’t understand the term dyspnea) Under what conditions does the dyspnea occur? o Do you have dyspnea with exertion? If so, how much activity do you have to do before you develop dyspnea? o Do you have dyspnea at rest? When did the dyspnea start? Since it developed, has it been getting better, worse, or remains unchanged? Do you have difficulty with breathing when lying flat (orthopnea)? Do you ever experience waking up from sleep and being short of breath (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea)? Do you ever notice any swelling of your feet or legs (edema)? Do you experience back pain or chest pain with the dyspnea? As well, Mrs. Melianos is a new patient and you have no past medical history, family history, or social history for her. Some specific questions related to this that are pertinent to her chief complaint include: Have you been taking any medications, either prescribed or over-the-counter? Have you ever smoked? If so how much and for how long? What jobs have you held in the past? o Did you ever have any jobs where you were exposed to dust, asbestos, or chemicals? Do you have any allergies? In your family does anyone have asthma or other lung disorders? Do you have any history of high blood pressure? Do you have any history of heart disease? Some additional questions that may help elucidate an etiology are: Have you been having any feelings of anxiety or panic? Have you had any trauma to your chest recently? Have you been experiencing any cough? Have you been experiencing any episodes of wheezing? Have you noticed any fevers, chills, or night sweats since the dyspnea began? Have travelled anywhere recently Mrs. Melianos answers all of your questions for you. She reports that she cannot tell you exactly when her shortness of breath began, but she does know that three years ago she did not have any problems with shortness of breath, unless she walked a long distance (>15 minutes of walking). She reports that now she has difficulty when she walks to the corner grocery store, which is one block from her house, but denies any dyspnea at rest. She does report, however, that she has had a chronic cough and that occasionally she is able to cough up a colorless sputum in the morning. She denies any episodes of orthopnea or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, as well as any edema, fever, chills, or night sweats. When you question her about her past medical history, she reports that she is currently a secretary at the local community college and has only ever worked as a housewife or a secretary. She reports that she used to smoke. When you further question her, you find out that she began smoking when she was around 15 years old and smoked ~1 ½ packs per day until she was 45 years old, at which point she stopped smoking and has not smoked since then. She denies ever having any allergies. She currently takes one aspirin a day because she heard that “…it is supposed to help my heart.” She reports that she is otherwise generally healthy and has no conditions for which she sees doctors or for which she takes medications. In what ways, if any, has this new information changed your differential diagnosis? Pertinent positives from Mrs. Melianos’ history: Progressively worsening dyspnea with exertion; onset appears insidious in nature Chronic cough with sputum production Positive history for 45 pack-years of cigarette smoking Pertinent negatives: No dyspnea at rest No orthopnea or PND No apparent occupational exposures No history of other significant medical conditions The information provided by Mrs. Melianos indicates a likely cardiopulmonary disease (dyspnea on exertion), although not severe enough at this time to have dyspnea at rest. Her history of 45 pack years of smoking puts her at significant risk for chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma, and her chronic cough with sputum production supports a pulmonary etiology. What are you going to look for on physical exam related to you differential? To further elucidate and refine your differential, a good physical exam is critical. Listed below are aspects of the physical exam, which may yield direct evidence of the etiology of the patient’s dyspnea. Components of Physical Exam Associated Conditions GENERAL What is the patient’s general Assessment of the patient’s general appearance? condition can help in assessing if this is Do they appear to be in respiratory a stable condition, or an acute distress? condition/exacerbation, which may potentially require intubation or other rapid measures. HEENT Nasal polyps or septal deviation Oropharyngeal/nasopharyngeal obstruction Postnasal discharge Allergies Expiratory pursing of lips Increased expiratory effort Inspiratory nasal flaring Lack of adequate air delivery/exchange NECK JVD (Jugular venous distension) CHF (Congestive heart failure) Hepatojugular reflex Bruits Valvular dysfunction/atherosclerotic carotid arteries Use of accessory muscles Increased work of breathing THORAX Increased AP (anteroposterior) Significant respiratory compromise, as diameter in cystic fibrosis or emphysema Evidence of trauma Can result in a pneumothorax Kyphosis or scoliosis Spine deformities which can restrict respiration Tachypnea (>20 breaths per minute) Many conditions, including anxiety, hypoxemia, and pain LUNGS – PERCUSSION Hyperresonance Hyperinflation of the lung; seen in emphysema, pneumothorax, or asthma Dullness/flatness Atelectasis, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or asthma LUNGS – AUSCULTATION Crackles (Rales) Disruption of air passing through the lower respiratory tract, especially in the small airways; often heard in pulmonary edema and pneumonia Rhonchi Passage of air through an obstructed airway; may be heard in asthma or tracheobronchitis Due to high-velocity air flow through a narrowed airway; heard with reactive airway disease (asthma),and acute and chronic bronchitis Stridor Heard with a foreign body CARDIOVASCULAR Tachycardia Present in many conditions, including hypoxia, hyperthyroidism, and heart failure Abnormalities in rate or rhythm May be due to atrial fibrillation Displacement of PMI Ventricular hypertrophy or dilatation Murmurs Valvular dysfunction S3 CHF Abnormalities in peripheral pulses Peripheral arterial disease ABDOMEN Hepatomegaly May be seen with CHF EXTREMITIES Edema Right-sided heart failure Cyanosis Hypoxemia, poor peripheral perfusion Clubbing Fibrotic lung disease (cystic fibrosis) or congenital heart disease resulting in chronic cyanosis PSYCHIATRIC Tremulous, sweating, nervous Potential anxiety disorder Wheezes For more information on this physical diagnosis of the respiratory system see: Seidel, Henry M; Ball, Jane W; Dains, Joyce E; Benedict, G William. 2003. Mosby’s Guide to Physical Examination. 5th Edition. Mosby, St. Louis. Chapter 12. During your exam you find: Normal head and neck exam Lungs are clear to auscultation except for an occasional wheeze diffusely throughout. The expiratory phase is slightly prolonged and there is tachypnea (20 breaths per minute). There is no evidence of use of accessory muscles. Cardiovascular exam is normal Abdominal exam is normal No edema, cyanosis, or clubbing of extremities Normal neurologic exam Positive chronic tissue texture changes and other TART findings in the T1-T5 area What initial testing would you like to have for this patient? While there are a number of different modalities that may yield information that is pertinent to your differential diagnosis, there are some simple and relatively inexpensive diagnostic tools that can be used, especially with the understanding that the most common causes of dyspnea are cardiopulmonary in nature. An electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, and CBC (or finger-stick hemoglobin) are all recommended as initial diagnostic tools. The results of these tests, in combination with your history and physical exam may warrant further, and more specific, testing. However, many of these should be considered as second-line tests. As well, please remember that Mrs. Melianos will also likely need to have a number of health maintenance issues addressed. While this is not the focus of this case, you would not be at fault to inquire about recent immunizations, etc. Test Results You discuss your ideas and plans for Mrs. Melianos with Dr. Sampson and your preceptor agrees with you. You schedule a follow-up appointment for Mrs. Melianos in 1 week and arrange for her to get a CBC, EKG, and chest X-ray (CXR) in the attempt to further elucidate the etiology of her dyspnea (although you think you already have a good idea of what the problem is!) Three days later your preceptor comes up to you and says that they have received the films from Mrs. Melianos’ CXR, however the report seems to have gone missing. Your preceptor asks you to look at the CXR and give your interpretation. What is your interpretation of the AP chest X-ray? Typical findings in a chest X-ray from a patient with COPD include: Flattened diaphragms Hyperinflated lungs Thin appearing heart and mediastinum Parenchymal bullae or suprapleural blebs in patients with emphysema Increased AP diameter (on a lateral CXR) Increased pulmonary vasculature Mrs. Melianos EKG and CBC are normal. You and your preceptor discuss Mrs. Melianos clinical, physical, and radiologic findings. You both agree that there is significant suspicion that Mrs. Melianos has COPD. Mrs. Melianos returns to the office for her scheduled follow-up appointment. She reports that she continues to have dyspnea and occasional cough. How are you going to explain COPD to Mrs. Melianos? An example of an explanation that you might provide Mrs.Melianos is: from what you have told me about your shortness of breath and cough, as well as what I observed from your physical exam and from the results of your EKG, blood work, and chest X-ray, we feel that you may have a condition known as COPD. Do you know anything about COPD? COPD stands for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and is most-likely a result of your previous cigarette smoking. In your case it is likely that your lungs were irritated and damaged by smoking cigarettes, and this has led to your lungs not working as well, thereby decreasing the oxygen available to your body. This is why you feel short of breath when you try to do physical activity. This is also likely the reason why you say you have to cough a lot, as the irritation from the smoking has caused your lungs to produce more mucus than normal. I know that this is a lot of information--what questions do you have for me?” Remember that it is likely that your patients will have many questions and may not understand or remember everything that you told them. It is important to remember to explain diseases and disease processes to patients in terms that are understandable to them. Refer them to sources of patient information that you have previously reviewed—it is better to send them to a source that you know has good factual information then to have them out “surfing the net” finding information that may not be 100% true. Some good patient education web sites on COPD: American Academy of Family Physicians. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). July 2004. Available at http://familydoctor.org/706.xml Pamet, Sharon MS; Lynm, Cassio MA; Glass, Richard M MD. JAMA patient page. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. JAMA. 290(17): 2362. November 5, 2003. Available at http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/290/17/2362 Mrs. Melianos thanks you for taking time to explain COPD to her, however she wants to know what the next step is going to be. The information that you have obtained from your history-taking, the physical exam, and diagnostic testing indicates that Mrs. Melianos has COPD. However, the diagnosis of COPD requires pulmonary function testing (PFT), including spirometry. PFT is also important for the management of COPD and other pulmonary diseases, as it is reproducible, quantitative, and allows longitudinal monitoring. For more information on pulmonary function testing see: Evans, Scott E. MD; Scanlon, Paul D. MD Current Practice in Pulmonary Function Testing. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 78(6):758-763, June 2003. At this point it would be a good idea to schedule a baseline Pulmonary Function Test, or Office Spirometry to determine the degree of obstruction or restriction that she has, as well as to determine if she improves with bronchodilators. You send Mrs. Melianos for spirometry and tell her to return for a follow-up visit in one week, at which point you will discuss the results of her pulmonary function testing with her and develop a specific management plan. It is one week later and you are about to see Mrs. Melianos at her follow-up appointment. Before going in to see her, you look at her spirometry results. Interpret the results of Mrs. Melianos’ PFT and explain how they support or refute your diagnosis of COPD Review of Spirometry: Spirometry: measures the volume of air inhaled or exhaled as a function of time Vital capacity (VC): amount (Volume) of air displaced by maximal inhalation or exhalation Total lung capacity (TLC): Lung volume reached after maximal inspiration Residual volume (RV): Volume of air remaining in lung after maximal expiration Forced expiratory vital capacity (FEVC, FVC): Patient forcefully expels air from a point of maximal inspiration until they reach maximal expiration Forced inspiratory vital capacity (FIVC): Forced inhalation from RV to TLC. FEV1: Forced expiratory volume in first second of the FVC maneuver Forced expiratory flow (25%-75%) (FEF25-75): the mean expiratory flow rate in the middle half of the FVC assessment Mrs. Melianos’ spirometry results indicate that she has obstructive lung disease. Obstructive lung disease includes asthma, COPD, and upper airway obstruction. It is characterized on spirometry by a decrease in FEV1 which is greater than the decrease measured in FVC, hence an overall decreased FEV1/FVC. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defines COPD as having a FEV1 of less than 80% predicted normal value and a FEV1:FVC ratio of less than 0.7. Restrictive lung disease is characterized by an overall decrease in total lung capacity (TLC). Restrictive lung disease can be due to (1) paraenchymal disease such as interstitial fibrosis or collagen vascular disease, or (2) extraparenchymal etiologies such as obesity or chest wall/spinal deformities. On spirometry, restrictive lung disease is defined as a FVC < 80%, often with a near equivalent decline in FVC and FEV1. The FEV1/FVC ratio is normal, or may even be increased, with the FEV1/FVC ratio being >0.7 in pure restrictive lung disease. The table below summarizes the typical spirometry result obtained in obstructive and restrictive lung disease. Obstructive Lung Disease Restrictive Lung Disease FEV1 Decreased (<80%) Decreased FVC Decreased FEV1/FVC Decreased (<0.7) Decreased (<80%) Normal (> 0.7) or Increased For a review of spirometry see: Gross, Thomas. Interpretation of Pulmonary Function Tests: Spirometry. University of Iowa Virtual Hospital. June 2002. Available at http://www.vh.org/adult/provider/internalmedicine/Spirometry/SpirometryHome How would you stage the severity of Mrs. Melianos’ COPD? There are a number of staging criteria that can be used to determine the severity of COPD, some of which use only results from spirometry, specifically FEV1, as that is a good reflection of the severity of obstruction. However, it has been recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) that you use not only results from spirometric evaluation, but combine these with patient symptoms to determine severity. In Mrs. Melianos’ case her FEV1 and symptoms place her in Stage II (moderate disease). Severity of airflow limitation in COPD (based on postbronchodilator FEV1) In patients with FEV1/FVC <0.7: GOLD 1 Mild FEV1 ≥80 percent predicted GOLD 2 Moderate 50 percent ≤FEV1 <80 percent predicted GOLD 3 Severe 30 percent ≤FEV1 <50 percent predicted GOLD 4 Very severe FEV1 <30 percent predicted FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC: forced vital capacity; respiratory failure: arterial partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) less than 60 mmHg (8 kPa) with or without arterial partial pressure of CO2 (PaCO2) greater than 50 mmHg (6.7 kPa) while breathing ambient air at sea level. From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD 2013, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), www.goldcopd.org. COPD Foundation system — The COPD Foundation has introduced a staging system that includes seven severity domains, each of which has therapeutic implications (figure 6) [8,37]. These domains are based upon assessment of spirometry, regular symptoms, number of exacerbations in the past year, oxygenation, emphysema on computed tomography scan, presence of chronic bronchitis, and comorbidities. Within these domains, the COPD Foundation uses five spirometric grades: ●SG 0: Normal spirometry ●SG 1: Mild, postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7, FEV1 ≥60 percent predicted ●SG 2: Moderate, postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7, 30 percent ≤FEV1 <60 percent predicted ●SG 3: Severe, postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio <0.7, FEV1 <30 percent predicted ●SG U: Undefined, postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio >0.7, FEV1 <80 percent predicted An advantage of this staging system is that it simplifies the interpretation of spirometry; any spirometric finding results in a classification, which is not the case in GOLD. Table 6: COPD Foundation guide to assessment of COPD severity COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC: forced vital capacity; SG: spirometry grade; PaO2: arterial tension of oxygen; CT: computed tomography. Reprinted with permission from the COPD Foundation. Slight modifications were made. (Thomashow B, Crapo J, Yawn B, et al. The COPD Foundation Pocket Consultant Guide. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases: Journal of the COPD Foundation. 2014; 1(1): 8387). Copyright © 2014 Informa Plc. Why do you think Mrs. Melianos is experiencing dyspnea now and not five years ago? Often there is significant compromise of lung function before patients begin to experience symptoms such as dyspnea. It has been postulated that symptoms often do not begin until after FEV1 reaches approximately 50% of predicted normal value. This is one reason why it has been recommended that patients greater than 40 years-old with a 10 pack-year history have spirometry performed as a screening method, even if they are asymptomatic. Now that you have a complete picture of Mrs. Melianos’ disease, what pharmacological therapeutic options should you consider in treating her COPD when it is stable (i.e. not an acute exacerbation)? There are a number of pharmacological options for the treatment of COPD. Unfortunately, nothing has been shown to cure the disease, but rather the principle of treatment is to decrease the symptoms of COPD and/or decrease the complications secondary to COPD. BRONCHODILATORS: The mainstays of pharmacological treatment of COPD are the bronchodilators, which are effective in COPD symptom management by increasing airflow and decreasing hyperinflation in the COPD patient. This results in a decrease in the symptoms of COPD, as well as decreasing the number of exacerbations and improving the quality of life for patients with COPD. Despite the evident subjective improvement of patients with COPD on bronchodilators, there are not always objective improvements (i.e. improvement in spirometry results) while on bronchodilators. The table below outlines the four major categories of bronchodilators based upon mechanism of action and duration. Category Short-acting B2-adrenergicreceptor agonists Short-acting cholinergicreceptor antagonists Long-acting B2-adrenergicreceptor agonists Long-acting cholinergicreceptor antagonists Example albuterol Duration 4-6 hours Ipratropium (Atrovent) 4-6 hours formoterol (Foradil), salmeterol (Serevent) tiotropium (Spiriva) 8-12 hours >24 hours At time of diagnosis, patients with COPD should be started on a bronchodilator (either short- or long-acting, and of either mechanism of action). If a patient fails single bronchodilator therapy, an additional bronchodilator of the other class should be added. For patients with COPD, a short-acting bronchodilator for acute relief of symptoms may also be useful. METHYLXANTHINES: If patients fail combined bronchodilator therapy, the addition of theophylline or aminophylline can be considered, as these have been shown to provide additional improvement in lung function and symptoms. However, the use of methylxanthines should be closely monitored, as they are potential toxic with significant side effects. Not in vogue as much due to the potential side effects. INHALED CORTICOSTEROIDS: Inhaled corticosteroids have not been shown to substantially modify airway inflammation in COPD, as assessed by spirometry, however, they do decrease symptoms, decrease the frequency of exacerbations, and increase general health status. As such, there does appear to be clinical benefit independent of measured FEV1 response, and it has been postulated that this is because inhaled corticosteroids both decrease the level of hyperinflation and result in a decreased number of exacerbations. They are recommended for COPD patients with moderate to severe airflow limitation who demonstrate no improvement of symptoms, no change in physiologic findings, and no decrease in the frequency of exacerbations despite maximization of bronchodilator therapy. SYSTEMIC CORTICOSTEROIDS: Systemic corticosteroids should not be used for routine management of stable COPD, but rather may be used for acute exacerbations. For one suggested treatment algorithm, see: Sutherland, E. Rand; Cherniack, Reuben M. Current Concepts: Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 350(26):2689-2697, June 24, 2004. What are other potential (nonpharmacologic) therapeutic options might you consider in the treatment of COPD? SMOKING CESSATION: The most important recommendation that could be made is that the patient stops smoking if the patient still does. It has been shown that patients who stop smoking and maintain abstinence have a 50% decrease in the rate of lung function decline. As Osteopathic Physicians, prevention or health maintenance is paramount for the patient. PATIENT EDUCATION: As always, patient education is important and necessary to helping patients learn to cope and understand their disease. PULMONARY REHABILITATION: Other options for the treatment of COPD include pulmonary rehabilitation, especially for patients who have significant dyspnea with exertion. This can include exercises and physical training, and is often more effective if coupled with patient education. OXYGEN: For treatment of hypoxemia, patients can be prescribed supplemental oxygen, which has been shown to improve the long-term course of COPD. Supplemental oxygen is recommended for patients with resting PaO2 < 55 mmHg or with an O2 saturation of 88% or less. SURGERY: Surgical options may also be available for patients with severe disease. For patients with severe emphysematous disease, lobar reduction surgery may be of use. Lung-volume-reducing surgery may be used for hyperinflation and removal of large bullae, which can compress areas of functional lung. Lung transplantation may also be an option for patients who would otherwise die within 1-2 years. OSTEOPATHIC MANIPULATIVE THERAPY: OMT can increase her range of motion of the rib cage along with regulating the sympathetic/parasympathic tone. Reference to Foundations for Osteopathic Medicine 2nd edition Pages 512-513, 1147 You go in to see Mrs. Melianos. When you walk in to the examination room Mrs. Melianos introduces you to her son, Nicholas. You explain to Mrs. Melianos the results from her spirometry evaluation and you ask her if she has any questions. She says that she has been reading on the Internet that COPD usually occurs in people who have smoked cigarettes, but that there is a genetic form of COPD as well, and she wonders if this could be why she has COPD, especially since she not longer smokes. What “genetic disease” she is talking about? 1-antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency is one of the less common causes of emphysema. It is due to a recessive genetic disorder where there is a deficiency of 1-antitrypsin (AAT), which is a protease inhibitor. Almost all people who have complete deficiency of this protein will develop emphysema. AAT deficiency is responsible for less than 5% of all cases of emphysema in the United States. This corresponds to ~100,000 Americans with the disease, however it is estimated that there are ~25 million American who are carriers of the gene. In the U.S. AAT deficiency is typically seen in people of Northern European descent. AAT deficiency-related emphysema typically manifests as dyspnea. with decreased exercise tolerance in the 4th decade of life. As such, AAT deficiency-related emphysema should be suspected in dyspnea patients who are less than 45 years old without other COPD risk factors. Treatment options for AAT deficiency-related emphysema are currently limited. There is the option for life-long replacement of AAT. As well, if diagnosed in children, there is the possibility for a liver transplant, as AAT is produced by the liver. You explain to Mrs. Melianos about 1-antitrypsin deficiency, and indicate that, given the lack of family history, her age at presentation, and her history of smoking, it isn’t 1-antitrypsin deficiency. Mrs. Melianos is relieved, however she tells you that she also read that exposure to second-hand smoke puts you at increased risk of developing COPD, and Mrs.Melianos says that she often smoked around Nicholas. She says that they didn’t know what they know now about how bad cigarette smoking is to our health. Discuss the relationship between cigarette smoking, second-hand smoke, and COPD. What is the relationship between smoking cessation and COPD mortality? Cigarette smoking is a significant risk factor for the development of COPD. It is currently estimated that 80-90% of COPD cases and deaths are attributable to cigarette smoking. Although cigarette smoking is the most significant risk factor, there are other risk factors for the development of COPD include air pollution, second-hand smoke, recurrent respiratory tract infections, a family history of COPD, AAT deficiency, and domestic or occupational pollutants. As previously discussed, smoking cessation is the single greatest intervention to decrease the rate of COPD progression. For patients who continue to smoke after diagnosis of COPD, they will likely continue to have an accelerated decline in FEV1 over time. For further information on smoking cessation in COPD see: Pride, N B Smoking cessation: effects on symptoms, spirometry and future trends in COPD. Thorax. 56 Supplement II:ii7-ii10, September 1, 2001. You decide to initially start Mrs. Melianos on tiotropium bromide (Spiriva) DPI (dry-powder inhaler) 1 inhalation daily and albuterol sulfate MDI (metered-dose inhaler) 2 puffs as needed for acute symptoms up to every four hours. You also perform OMT on Mrs. Melianos since you found thoracic and rib dysfunctions on exam. She seems happy with her treatment plan. You send her home with a follow-up appointment scheduled in 2-3 weeks for more OMT and to see how she is doing on her Rx. Dr. Sampson comments that he is noticing more and more women being diagnosed with COPD and asks you if you wouldn’t mind doing a little research on the epidemiology of COPD. The incidence of COPD in the U.S. is reported at between 11 and 14 million people, and believed to affect ~20% of the adults in the U.S. COPD is currently the 4th leading cause of death in the U.S., resulting in the mortality of 120,000 Americans in 2002. Additionally, COPD is predicted to be the third leading cause of death by 2020. Despite the wide prevalence of COPD diagnosed in the adult population, it is estimated that 24 million adults have evidence of impaired lung function, indicating an under-diagnosis of COPD in the U.S. currently. While COPD used to be more prevalent in males, since 2000 the number of deaths attributed to COPD has been greater in females than in males. When adjusted for age, the COPD death rate for females has increased from 20.1 to 56.7 per 100,000 population from 1980 to 2000, respectively. It is hypothesized that the incidence of COPD was delayed for women because popularity of smoking in women occurred ~20 years after the popularity for men. Therefore it is only now that we are seeing the true effects of smoking in women (i.e. COPD), whereas 20 years ago the effects were evident in men. As well, the prevalence of self-reported COPD has been shown to be greater in females than males and greater in whites than blacks. For more information on the prevalence of COPD, see: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Data Fact Sheet. March 2003. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/lung/other/copd_fact.pdf. What would you say to the other medical student about COPD versus emphysema versus chronic bronchitis? Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a term used to describe a physiologic situation where there is progressive airflow obstruction which is irreversible. There are two major diseases which fall under the heading of COPD, chronic (obstructive) bronchitis and emphysema, which frequently co-exist, thereby defining a patient as solely one or the other is often futile. There is some debate about the inclusion of asthma, however the airflow obstruction experienced in asthma is reversible with administration of a bronchodilator, unlike the irreversible nature of COPD. Chronic bronchitis is defined as excessive cough with sputum production for at least three months in at least two consecutive years. The excessive cough is attributable to increased mucus production secondary to inflammation of the lining of the bronchial tubes. The increased volume of mucus also leads to improper clearing of the bronchial tubes, which results in an increased risk of bacterial infections and airway obstruction. In emphysema, lung damage results in alveoli not being able to stretch and recoil, as they have become stiff. This results in air being trapped in the alveoli, which then impedes O2/CO2 exchange. Patients with emphysema often report chronic cough, dyspnea, and limited exercise tolerance. Six months later you are doing your Internal Medicine rotation with Dr. Parish and you see that Mrs. Melianos is on your service! In morning report you hear that she was admitted for “COPD Exacerbation”. What is COPD Exacerbation? COPD exacerbations are temporary worsening of the patient’s obstructive symptoms. During an exacerbation there is often an increase in baseline sputum production and dyspnea, and sputum typically becomes more purulent in nature. Exacerbations are typically linked to acute infections, but they can also be triggered by certain weather conditions, allergens, pollutants, heart failure, and noncompliance. Exacerbations can often require hospitalization for patients with COPD because there can be a rapid decline in function, resulting in significant respiratory distress. Bacterial infections are implicated in 70 to 75% of exacerbations. The most common infectious causes of COPD exacerbations are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Pseudomonas species are associated with more severe exacerbations, which are more likely to occur in patients with severe disease and frequent exacerbations. For additional information, refer to the case on pneumonia and see: Hunter, Melissa H. MD; King, Dana E. MD. COPD: Management of Acute Exacerbations and Chronic Stable Disease. American Family Physician. 64(4): 603-612. August 15, 2001. Available at http://www.aafp.org/afp/20010815/603.html. What additional health maintenance issues should Mrs. Melianos be aware of in the future to potentially help prevent further exacerbations? Although there is little evidence that there is a direct benefit of vaccinating people with COPD, it is currently standard practice to recommend pneumococcal and annual influenza vaccinations, in the attempt to decrease disease-specific and general mortality. What is cor pulmonale and how is it related to COPD? Cor pulmonale refers to pathologic changes in the right ventricle due to a primary respiratory disorder. There are a number of potential etiologies of cor pulmonale, however it is estimated that COPD is responsible for greater than 50% of the cases of chronic cor pulmonale. Pulmonary hypertension is often viewed as the link between the primary respiratory disorder and the subsequent development of right ventricular hypertrophy and eventually right-sided heart failure. What factors for any patient with COPD are going to indicate an increased risk of mortality? The strongest predictors of mortality are (1) older age, and (2) progressive decline of FEV1 with serial testing. The decline of FEV1 is most associated with continued cigarette smoking. Other factors associated with a less favorable prognosis (increased rate of mortality): FEV1 < 750 cc (<50% of predicted value) Lower diffusion capacity Hypoxia with PaO2 < 55 mmHg Continued tobacco use Hypercapnia with PaCO2 > 45 mmHg Right-sided heart failure (cor pulmonale) Malnutrition Resting tachycardia What are the gross pathologic changes expected in a COPD lung? (This one was for Dr. Santo and Dr. Dudley) Shown below images of an emphysematous lung, as compared to a normal lung. In the emphysematous lung there are large dilated airspaces (bullae) which are evident throughout the lung. In chronic bronchitis there is often evidence of mucus plugging. Cross-section of emphysematous lung. Emphysematous bullae. Normal Lung. Images courtesy of Department of Pathology, Penn State College of Medicine, Pennsylvania.(home of Joe Paterno and the Orange Bowl Champ Nittany Lions) Readings: Rakel’s Textbook of Family Medicine: pp243 - 251