Before You Get There

advertisement

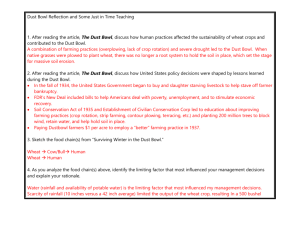

“analytical description of your interaction with the book” very emotional connection words sparse like the fields no wasted energy introspective thoughtful poingnant understated response to the drama of mother, hands, makes understated response to dust more powerful. Barrren Grateful for things we don’t even consider -- rain, breathing easy, birds, clear day. What do we need that we don’t appreciate till it is gone, ruined, in jeopardy? Environmental themes in this book? Effects of poor land use practices Humans at mercy of land - powerlessness Gratitude for rain Night bloomer -- scorched by sun Big dust storms of Black Sunday, etc-- info is on web, but this gives an immediacy Federal disaster relief Migrants v those who stayed Trees, “wheat’s not meant to be here” Strong emotional impact of US History event (What is it like now?) greed/shortsightedness, or in less judgemental words-- joy in productivity, unawareness, lack of control over consequences. Role of govt? Shows up here as relief, money to replant wheat. Portrayals of interactions with the natural and technological world? Trucks unable to operate in the dust Failure of technology vs natural world “we didn’t see it coming, even though it had been making its way towards us for a long time.”?” In Amarillo, p.20-- wind ruins plate glass, neon signs, and wheat-- all unnatural human things destroyed by wind. How would you utilize this book to challenge and expand your students’ thinking concerning a particular environmental issue or issues? “Thousand Steps”-- heading straight for us. What could have been done? What was the cost? Can we really weigh prevention in? Would these people have been unwilling to change their practices? Why or why not? Emotional connection to the results of poor land use practices. Makes things immediate, strong and real. What is happening today that is comparable? Rainforests? What about OK area today? Kay Berglund 2/15/00 Environmental Science “A Thousand Steps to Take Before You Get There” The Dust Bowl was an ecological and human disaster that took place in the southwestern Great Plains region of the United States in the 1930's, including parts of Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, and Colorado. It was caused by misuse of land and years of sustained drought. Before farmers came, the region was covered by hardy grasses that held the soil in place in spite of the long recurrent droughts and occasional torrential rains characteristic of the period. However, in the thirty years before World War I, a large number of homesteaders settled in the region, planting wheat and row crops and raising cattle. Both these land uses left the soil exposed to the danger of erosion by the winds that constantly sweep over the area. Beginning in the early thirties, the region suffered a period of severe droughts, and the soil began to blow away. . . . Millions of hectares of farmland became useless, and hundreds of thousands of people were forced to leave their homes.1 We have all read paragraphs like that one before. “Human tragedy as a result of poor land use” is a theme that recurs from the Dust Bowl in the 1930’s in the Great Plains, to the flooding in the Mississippi Valley in 1993, to the fires in Indonesia in the last few years. “Many have been forced from their homes,” the newscasters say somberly, and then it’s on to the sports and local weather report. But Karen Hesse’s Out of the Dust does not let a reader respond with an intellectual “tsk-tsk” at poor ecological judgement. It grinds dust under your eyelids, and makes you feel the mud in your spit. The Dust Bowl is not just another ecological tragedy, not just another episode of U.S. History to study about for that A.P. exam. Instead, we see and feel and choke on the wind-blown soil with Billie Jo, a thirteen-year-old girl living in the drought and wind and dust in Oklahoma in the 1930’s. 1 http://www.ultranet.com/~gregjonz/dust/dustbowl.html The Dust Bowl storms weave in and out of the plot of this story. Hesse gives us Billie Jo’s thoughts in free verse, with words as sparse as the Oklahoma fields where wheat once grew. The brevity of these words at times holds their power, as in this poem entitled, “Almost Rain”2 It almost rained Saturday. The clouds hung low over the farm. The air felt thick. It smelled like rain. In town, the sidewalks got damp. That was all. November 1934 Part of what we feel, as readers of this poem and this story, is the decision of Billie Jo’s family to stay on their farm, despite the hardship they face. Hundreds of thousands of people became migrants during these droughts, but many more stayed with their land, hoping to wait out the rain. This story tells the same lessons that a factual summary of the Dust Bowl conveys: overfarming, urged on by the high prices for wheat during WWI, removed the native grasses across the Great Plains and replaced it with wheat, whose roots could not hold the water during times of drought. The problem then became a vicious cycle, as the sparse surviving wheat was blown away, and rain that did come ran off the hard dry soil, taking seed and seedling along with it. But one of the truisms of teaching is to show rather than tell. A recounting of the factors that led to the Dust Bowl tells what happened and why; this story shows the real human impact, the complicated reasoning, and the emotional toll these storms and this drought caused. Billie Jo’s parents put the problem in emotional terms, as her father says, “It has to be wheat./ I’ve grown it before./ I’ll grow it again,” to which her mother replies, “The wheat’s not meant to be 2 Out of the Dust, p.88. here.”3 We feel both the tragedy and the complexity of the tragedy, how the people living in this area both created and suffered at the mercy of this natural disaster. And how much more powerful is this lesson about land use, than learning about runoff and crop rotation in narrow “scientific,” emotionless terms? After I read this story, I immediately wanted to know more about this period in U.S. history, and I searched the internet for information about these years. In a classroom, this story could serve the same purpose. A factual description of Black Sunday: April 14 Black Sunday. The worst "black blizzard" of the Dust Bowl occurs, causing extensive damage.4 magnifies in intensity when we page back through the book and realize this must have been the storm Billie Jo called “Blankets of Black.” Reading this book brings a remote event, which happened in another part of the country, when our grandparents (our students’ great-grandparents) were young, into the immediacy of a real event that happens to someone you know, because we feel like we know Billie Jo by the end of the story. After reading this story, or while reading it, we can learn much more readily the causes for this disaster, and the lessons we have learned (some say not well enough) from it. Out of the Dust is also a powerful book in its ability to let us feel gratitude and happiness for things we usually take for granted: a clear day, birds in the sky, gentle rain, clean air, a flower that blooms. It asks us to ask ourselves what we love and need about the natural world, before the beauty changes and every breath or beat of wings or unfolding petal becomes a struggle. Without lecturing or admonishing, this book lets us feel the spirituality that David Orr urges in Earth in Mind. Even as it explores a drastic natural catastrophe, Out of the Dust resists the urge 3 4 p.40 http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/dustbowl/timeline/index.html to paint nature as evil. Instead, through rapturous descriptions of snow and rain and night-blooming cereus, juxtaposed with drought, wind, and waves of dust, we feel the spectrum of the natural world in whose arms we are held. Hesse’s depiction of technology and the encroachment of intense farming into the Great Plains is gentle in its lessons. The wheat is the most prevalent image of human-made impact on the land, and it is likened to more obviously unnatural objects in such passages as this one: wind blew plate-glass windows in, tore electric signs down, ripped wheat straight out of the ground.5 in which two clearly human-created objects are set in parallel to the wheat, which is also destroyed by the wind. Though one of our favorite American songs equates “purple mountains majesties” with “amber waves of grain,” we see in this story that the fields of wheat exist because of determined human intervention. The natural state of these plains, so much more in balance through wet and dry cycles, is “grass and wild horses and wolves roaming,”6 not the wheat whose shallow roots caused devastation by the wind. We can learn a lesson from Hesse in her gentle approach; how much more effective whispering can be than strident polemicized argument. This is not an easy book, and we would need to use caution with a young audience. Billie Jo’s mother dies, and Billie Jo suffers horrible injury to her hands halfway through the story. As a teacher who wants to protect her students, part of me wanted to edit these scenes from the book, but as I reflect more thoughtfully on their role, I do not think they can be excised so easily. Part of what these tragedies do is give us a comparison. As we see how Billie Jo 5 6 p.20 p. 107 responds to these events, and we cry (even when she does not) for her loss of her mother and of the joy music brought her, we gain greater understanding of the way she responds to the dust, and we have a context for the sparse emotion she shares with us. One of the most didactic passages in this story comes from Miss Freeland, Billie Jo’s teacher, as she describes the reasons for the dust storms. The words in this poem echo the words in many textbooks about this time in our history, but as we hear them through our narrator’s ears, we feel the gravity of each step on this path. Miss Freeland says, Without the sod the water vanished, the soil turned to dust. Until the wind took it, lifting it up and carrying it away. Such a sorrow doesn’t come suddenly, there are a thousand steps to take before you get there. Billie Jo’s response to this lesson puts into words the problem we face with every environmental issue; namely, that it sneaks up on us, that even when we cause it and can later say exactly how and why, we do not see it coming, or do not truly know what it will mean, as it comes slowly towards us. Billie Jo says, But now, sorrow climbs our front steps big as Texas, and we didn’t even see it coming, even though, it’d been making its way straight for us, all along.7 In this poem resides a lesson that we could apply to nearly every issue, every sorrow that we face in environmental education. How do we see what is heading straight for us, and how do we change a course of a thousand steps? 7 p.84