TINKER V - DuBois Area School District

advertisement

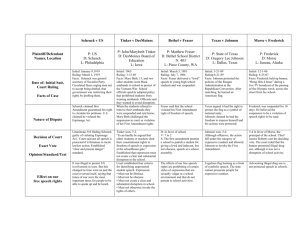

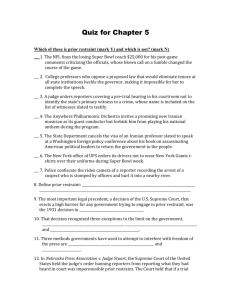

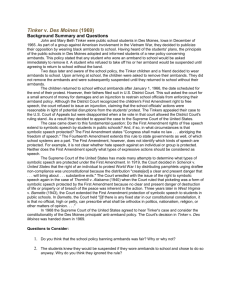

TINKER V. DES MOINES INDEPENDENT COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT In the landmark case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503, 89 S. Ct. 733, 21 L. Ed. 2d 731 (1969), the U.S. Supreme Court extended the First Amendment's right to freedom of expression to public school students. The ruling, which occurred during the Vietnam War, granted students the right to express their political opinions as long as they did not disrupt the classroom. The Court made clear that public school administrators and school boards could not restrict first amendment rights based on a general fear of disruption. The case grew out of political opposition to the Vietnam War. In December 1965 a group of students in the Des Moines public school system decided to protest the war. John Tinker, 15 years old, his 13-year-old sister Mary Beth, and 16-year-old Christopher Eckhardt sought to publicize their antiwar position and their support for a truce by wearing black armbands to school in the weeks leading up to the Christmas holidays. School administrators became aware of the plan to wear armbands and immediately adopted a new policy that prohibited the wearing of armbands. Students who refused to remove them would be suspended until they agreed not to wear them. The three students, who were aware of the policy, arrived at their schools a few days later wearing the armbands. They were promptly suspended and sent home. They did not return to school until after the holiday season, when their planned protest period had expired. The three teenagers filed a civil rights lawsuit in federal court through their fathers, asking that the court issue an injunction that would bar the school system from disciplining the students. The district court sided with the school board, concluding that the schools had acted reasonably to prevent a disturbance of school discipline. The Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld this ruling on an evenly divided vote. The students then brought their case to the Supreme Court. The Court, in a 7–2 decision, overturned the lower court rulings. Justice abe fortas, in his majority opinion, stated at the outset that students and teachers do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse door." However, he acknowledged that the Court had upheld the authority of school officials to "prescribe and control conduct in the schools." Thus, the issue before the Court concerned the area where the First Amendment rights of students collided with the rights of school administrators to maintain order and discipline. Justice Fortas noted that the actions taken by the three students had not been disruptive or aggressive. The protest was a "silent, passive expression of opinion," that had led to the suspension of only five students out of the 18,000 enrolled in the Des Moines schools. Though a few hostile comments had been made to the students who were wearing armbands, there had been no threats or acts of violence. Based on this factual record, Fortas found puzzling the district court's finding that the school had reasonable grounds for barring the armbands. The principals may have had general and nonspecific fears of a disturbance, but such fears were not sufficient to overcome the students' First Amendment rights. He pointed out that any departure from the normal school regimen was liable to cause trouble. However, the risk of a word or symbolic expression causing a disturbance was the "sort of hazardous freedom" that made the country strong and vigorous. The school system could not ban a particular expression of opinion unless it could show its actions were based on more than the "mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint." In the case of the Des Moines schools there had been no findings that the armbands would substantially interfere with school operations or harm the rights of other students. Justice Fortas concluded that the principals sought to avoid controversy concerning the Vietnam War. This conclusion was reinforced by the fact that the schools had banned only the black armbands. The schools permitted students to wear political campaign buttons and even the Iron Cross, which was a symbol of Nazism. Students could not be singled out for their political views without that action being a violation of the First Amendment. Justice Fortas concluded his opinion with a lecture on free speech and public schools. He stated that public schools were not "enclaves of totalitarianism," with school officials wielding absolute authority over their students. Students could not be regarded as "closed-circuit recipients" of state indoctrination. Therefore, absent a specific demonstration of "constitutionally valid reasons to regulate their speech, students are entitled to freedom of expression of their views." Students were entitled to this freedom whether in a classroom, a hallway, a cafeteria, or an athletic field. Absent a showing by school officials that the expression "materially disrupts class work or involves substantial disorder or invasion of the rights of others," students must be guaranteed freedom of speech. In Fortas's view, freedom of speech was not confined to a "telephone booth or the four corners of a pamphlet, or to supervised and ordained discussion in a school classroom." Because the three students had not disrupted their schools with their passive displays of political protest, they were protected by the First Amendment. Justice hugo black, in a dissenting opinion, angrily lamented the Court's endorsement of permissiveness. He argued that the conduct in question had been disruptive and that school officials had the right to control their classrooms. Black stated that it was a "myth to say that any person has a constitutional right to say what he pleases, where he pleases, and when he pleases." Teachers were hired to teach, and students were sent to school to learn; neither teacher nor students were sent into publicly funded schools to express their political views. Black foresaw an ominous future where students used the Court's decision to assert total control of their schools. Justice Black's prophecy proved false. In addition, the Supreme Court issued decisions in the coming years that gave more power to school administrators to regulate student conduct. Nevertheless, the Tinker decision changed the legal landscape for students who sought to exercise their First Amendment rights. Bethel School District v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986), was a United States Supreme Court decision involving free speech and public schools. On April 26, 1983, Matthew Fraser, a Spanaway, Washington, high school senior, gave a speech nominating classmate Jeff Kuhlman for Associated Student Body Vice President. The speech was filled with sexual innuendos, but not obscenity, prompting disciplinary action from the administration. Fraser's speech was as follows: "I know a man who is firm - he's firm in his pants, he's firm in his shirt, his character is firm - but most [of] all, his belief in you the students of Bethel, is firm. Jeff Kuhlman is a man who takes his point and pounds it in. If necessary, he'll take an issue and nail it to the wall. He doesn't attack things in spurts - he drives hard, pushing and pushing until finally - he succeeds. Jeff is a man who will go to the very end - even the climax, for each and every one of you. So please vote for Jeff Kuhlman, as he'll never come between us and the best our school can be. He is firm enough to give it everything." [Long pause after the word "come" on oral delivery, but no comma in the written version, according to Matthew N Fraser] After appealing through the grievance procedures of his school, he was still found to be in violation of a school policy against disruptive behavior. These grounds later evolved to include obscenity at trial, but obscenity, according to Fraser, was not listed as grounds for his punishment in his initial hearing with school vice-principal Christy Blair. Fraser was suspended from school for two days as a result, was prohibited from speaking at his graduation ceremony, and his name was stricken from the ballot used to elect three graduation speakers. Fraser nonetheless was selected by a write-in vote which placed him second overall among the top three finishers, although Bethel High School administrators refused to accept the write-in vote as a valid result, and continued to deny Fraser the opportunity to speak at graduation. With approval from his parents and help from ACLU cooperating attorney Jeff Haley, Matt Fraser filed a lawsuit against the school authorities claiming a violation of his First Amendment right to free speech, and U.S. District Court judge Jack Tanner ruled in his favor. The school district then appealed to the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which ruled in Fraser's favor with a broadly worded opinion. The school district asked the United States Supreme Court to consider the case and it agreed to do so. The US Supreme Court reversed the Court of Appeals in 7-2 vote to uphold the suspension, saying that the school district's policy did not violate the First Amendment. Chief Justice Warren Burger delivered the Court's opinion, in what ended up along with the Graham Rudmann decision to be the final case of the Burger Court era. Fraser refers to this as "the silver lining in the grim cloud of my defeat." Justices William J. Brennan and Harry Blackmun delivered concurring opinions, while Thurgood Marshall and John Paul Stevens dissented. Though the Court distinguished its 1969 decision Tinker v. Des Moines, which upheld the right for students to express themselves where their words are nondisruptive and could not be seen as connected with the school, the ruling in Fraser can be seen as a limitation on the scope of that ruling, prohibiting certain styles of expression that are sexually vulgar. High court backs school dress code in T-shirt case By Greg Moran STAFF WRITER March 6, 2007 POWAY – The U.S. Supreme Court has declined to suspend a dress code at Poway High School that is at the center of a continuing legal fight over free speech and religious rights. Tyler Chase Harper, a Poway High School student, sued the Poway Unified School District in 2004, saying his rights to freedom of speech and religion were violated when he was pulled out of class for wearing an anti-gay T-shirt. Harper wore the shirt during the school's “Day of Silence,” which is meant to promote tolerance of gays and lesbians. Harper, who says he is a Christian, contended his religion compelled him to speak out. He put masking tape on a T-shirt and wrote “I Will Not Accept What God Has Condemned” on the front, and “Homosexuality Is Shameful, Romans 1:27” on the back. He at first sought an injunction preventing the district from enforcing a policy aimed at eliminating “hate behavior” that offended students in racial, gender, sexual preference or other minority groups. Both a San Diego federal judge and the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals had ruled against Harper's bid for an injunction. The Supreme Court affirmed those earlier rulings yesterday, in an 8-1 ruling. But the closely-watched case – which legal experts said could again reach the high court – remains very much alive. The ruling yesterday, which dealt only with the injunction part of the case, was not unexpected. In January, U.S. District Court Judge John A. Houston ruled in favor of Poway on the the broader and more substantive issues in the case. Houston found the school's actions didn't infringe on students' rights of free speech and free exercise of religion, nor did he find them hostile to a particular religious viewpoint. It is Harper's appeal of that ruling that is expected to be the vehicle for settling the constitutional battle over religious freedom and free speech, said Jack Sleeth, the school district's lawyer. Harper's attorney, Kevin Theriot, said yesterday's Supreme Court decision was important because it also deemed moot an earlier appeals court ruling that seemed to greatly expand school district's power to ban speech that demeans students based on their status as minorities. He said the high court has wiped away that ruling, which he called “one of the worst opinions on student speech in years.”