SAFE INJ

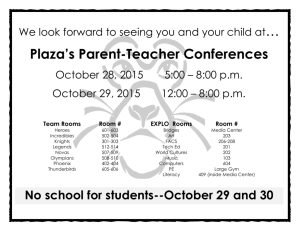

advertisement

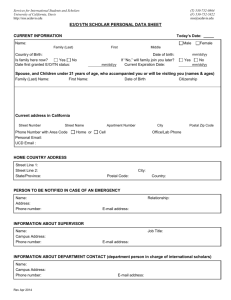

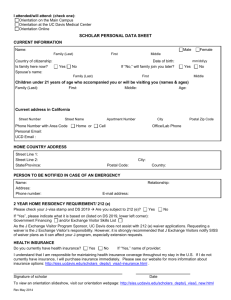

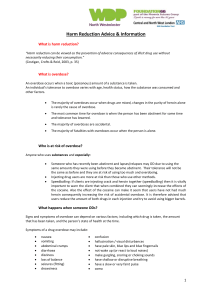

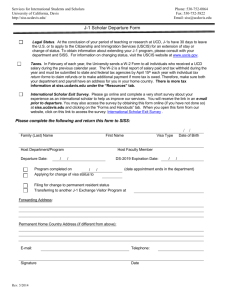

A RAPID REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE FOR THE EFFECTIVNESS OF SAFE INJECTION SITES BACKGROUND Safe injection sites (SISs) [synonyms = drug consumption rooms; supervised injection sites/centres] are professionally supervised health care facilities, where drug users can use drugs in safe, hygienic conditions. They comprise a highly specialised drugs service within a wider network of services for drug users and usually operate from separate areas located in existing facilities for drug users or the homeless. The overall rationale for SISs is to reach and address the problems of specific, highrisk populations of drug users, especially injectors and those who consume in public. The specific objectives of SISs are to: establish contact with difficult to reach populations of drug users; provide a safe and hygienic environment for drug consumption, in particular, injecting drug use; reduce mortality and morbidity associated with drug use, as a result of overdose, transmission of HIV and hepatitis, and bacterial infections; promote access to other social, health and drug treatment services; reduce public drug use and associated nuisance1 Centres have been established world wide and are located in e.g. Australia, Canada, Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland. . The establishment of these centres is controversial and according to the Beckley Foundation there are three broad areas of controversy about SISs.2 1. There is an issue of principle. How do policy makers justify providing a service that enables people to engage legitimately in activities which are both harmful and illegal? 2. There is an issue about messages. Do SISs legitimise drug use, encourage more people to use hard drugs or – at the local level – increase drug-related problems in the areas where they are situated? 3. There is an issue of effectiveness. Do SISs reduce drug related harms and, even if they do, are they the most appropriate and cost effective way of reducing these harms? 1 European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2004), European report on drug consumption rooms, EMCDDA, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Available at: http://www.emcdda.eu.int/?nnodeid=1327. Accessed 09/04/06 2 Roberts M; Klein A; Trace M. Drug Consumption Rooms. DrugScope and The Beckley Foundation . A DrugScope Briefing Paper 2004 Dr M Webb, Vesion 1, April 2006 1 THE TECHNOLOGY/SERVICE DESIGN SISs are official services, funded from local or regional budgets or by voluntary organizations. The rooms are supervised by social workers, nurses, doctors or other staff trained in emergency care and social assistance to drug users. They are distinct from illegal ‘shooting galleries’, which are run for profit by drug dealers, as well as from consumption facilities provided within the framework of drug prescription programmes, where drugs are supplied to users. PATIENT GROUP Illegal drug users of all ages RESEARCH EVIDENCE Table 1 shows the results of a rapid review of the literature using the major databases. Language restrictions in the search were French, German & Spanish. Review evidence was first sought; the primary studies contained in such reviews were not individually critically appraised. TABLE 1 DATABASE SEARCH TERM/S OVID 1966-2006 Cochrane DSR ACP Journal Club DARE CCTR EMBASE PsychINFO Sumsearch Combination of :Community health services/HIV infections/Hepatitis C/Humans/Risk-taking/safety management/substance abuse, intravenous/syringes Google scholar Google HMIC INAHTA NICE National Horizon Scanning Centre National Research Register Current Controlled Trials Safe/secure/injection/sites; drug consumption rooms Safe/injection/sites; drug consumption rooms Safe/injection/sites; drug consumption rooms Combination of: Community health services/HIV infections/Hepatitis C/Humans/Risk-taking/safety management/substance abuse, intravenous/syringes Safe/injection/sites; drug consumption rooms NUMBER OF HITS/NUMBER SELECTED FOR RELEVANCE 444/10 15/1 39/2 39,000/9 2300/1 6/0 The rapid review did not reveal any Level 1 (systematic review, meta-analyses, randomised controlled trial) type evidence. There were not any details of centres within the United Kingdom, apart from a centre in Greater Manchester, that has been nominated for an NHS Award 2006 Dr M Webb, Vesion 1, April 2006 2 The 2004 report from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction1 evaluated the evidence for effectiveness of SIS. The review identified a large number of studies that describe the outcome of consumption rooms or discuss their relevance in the context of a local harm reduction strategy. The results from this evaluation about the effectiveness of SISs are summarised below:-. Ability to attract difficult to reach drug users SISs reach their defined target population, including street users and older, long-term users who have never been in treatment. There is no evidence that they recruit drug users into injecting. To achieve adequate coverage and high rates of regular use, it is necessary to provide sufficient capacity relative to the estimated size of the target population, to locate rooms on sites that are easily accessible and to ensure that opening hours are long enough to meet demand, especially in the evening. Rooms targeting drug-using sex workers also need to be appropriately situated and remain open in the evening and night. Provide a safer injecting environment SISs achieve the immediate objective of providing a safe place for lower risk, more hygienic drug consumption without increasing the levels of drug use or risky patterns of consumption. Health education at SISs encourages sustainable changes in risk-taking behaviour by some clients and contributes to reducing drug-related health damage among a difficult to reach target group. Decrease the incidence of infection associated with drug use A lack of studies combined with methodological problems associated with isolating the effect of SISs, mean that no conclusions can be drawn about the direct impact on infectious disease incidence. Decrease incidence of drug-related deaths Where coverage is sufficient and access and opening hours are appropriate, SISs may contribute to reducing drug-related deaths at a city level. Increase access to social, health and drug treatment services SISs increase access to drug services and health and social care. In so doing, they promote the social inclusion of a group of extremely marginalised problem drug users. Dr M Webb, Vesion 1, April 2006 3 Besides supervision of drug consumption, other services are usually delivered on site. Low-threshold medical care and psychosocial counselling services are especially well used and contribute to stabilisation of and improvement in the physical and psychological health of service users. The UK Harm Reduction Alliance (UKHRA) was funded by the National Treatment Agency (NTA), to carry out a consultation exercise in March 20053. This consultation aimed to gather the views of key stakeholder organisations on what action is required in relation to drug treatment and harm reduction to reduce the impact of blood borne viruses and overdose. The piloting of SISs and safer injecting spaces was indicated as one of the priorities within a national treatment strategy based upon harm reduction. In the 2004 report, produced by the UK organisation DrugScope for the Beckley Foundation Drug Policy Programme2, the situation in the UK for the establishment of SISs is discussed. They cite the fact that the report of the Home Affair’s Select Committee in 20014 concluded ‘that there is a strong case for bringing heroin use above ground, so that those who wish to be helped can at least indulge their habit at minimum risk to their own health and that of the public and the obvious first step is the introduction of safe injecting houses’. A comprehensive review of the evidence-base has concluded that SISs ‘show promise and require cautious expansion with evaluation in ways that are adapted to local settings’.5 A review by Kimber6 et al concluded that the available evidence suggests that SISs are: engaging the targeted client groups, reducing public nuisance associated with open drug scenes, reasonably well accepted in their local communities, successfully managing drug overdose, contributing to stabilization or improvements in health and risk behaviours interfacing between relevant health and social welfare services. reducing overdose deaths in several German cities. There has been considerable work performed on SISs in Australia and the 18 month evaluation of a SIS in Sydney 7 illustrates the problems of evaluating SISs. Table 2 shows the results of the evaluation. It can be seen that only modest benefits were demonstrated and 3 UK Harm Reduction Alliance Consultation Exercise. Available at: http://www.ukhra.org/Resources/ukhra_report_stakeholder_interviews.pdf. Accessed 07/04/06 4 Home Affairs Select Committee (2001), The Government’s drug policy – Is it working?, HASC, London. 5 Hunt N. A review of the evidence-base for harm reduction approaches to drug use ( and Summary), Forward Thinking on Drugs 2003, Release, London 6 Kimber J, Dolan K, Van Beek I, et al. Drug consumption facilities: an update since 2000. Drug and Alcohol Review,2003; 22: 227-233. 7 MSIC Evaluation Committee (2003), Final report on the evaluation of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre, Sydney. Available at: http://www.druginfo.nsw.gov.au/data/page/255/msic.pdf. Accessed 08/04/06 Dr M Webb, Vesion 1, April 2006 4 further analysis has concluded that the evaluation was hampered by the confounding effect of a reduction in supply of heroin to Australia that had occurred prior to the study. Formal clinical trials of SISs are required with control of potential confounding but these will be difficult to perform. TABLE 2 Final Report of the Evaluation of the Sydney Medically Supervised Injecting Centre (MSIC) Some key statistics • During the 18 month trial 3,810 individuals registered to use the MSIC. Around two thirds had been in treatment at some time, and about one quarter in the previous 12 months • 73% were male, the average age was 31 and the average period they had been injecting was 12 years. • Heroin accounted for 61% of visits, cocaine for 30%. • Additional health care services were provided to clients in approximately one in four visits. • 1,385 referrals for further assistance were made on behalf of 577 clients, 43% were for drug treatment, 32% for primary health-care and 25% for social welfare services. 20% were confirmed to have resulted in the client making contact with the relevant agency. • 409 drug-overdose related incidents requiring clinical management occurred at the MSIC, a rate of 7.2 overdoses per 1000 visits. • Following the opening of the MSIC, there were reductions in opioid overdose ambulance attendances in the Kings Cross Area, but these had already been falling, and it was not possible to distinguish the role of the MSIC from the effect of a continued reduction in heroin availability. • There was no evidence that the operation of the MSIC affected the number of heroin overdose deaths in the Kings Cross area. But, on the basis of clinical and epidemiological data on heroin overdose outcomes, at least four deaths per year are estimated to have been prevented by clinical intervention of staff at the MSIC. • There was a small decrease in the frequency of injecting related problems among MSIC clients. • Nearly half of MSIC clients reported that their injecting practices had become less risky. • The frequency of public injection among MSIC clients decreased. • In 2002, 9% said that they injected more frequently and 22% less frequently since using the facility. • Kings Cross residents and businesses reported sighting fewer episodes of public injecting and syringes discarded in public places. • Syringe counts in Kings Cross were generally lower after the MSIC opened than before. COST EFFECTIVENESS No data of relevance to the UK were identified.. ONGOING RESEARCH No trials were identified. CONCLUSIONS There was no Level 1/high quality evidence found for the effectiveness of SISs. The available evidence indicated that SISs only have a modest effect on outcomes when taken in isolation from other policy and service initiatives. Evidence from both Europe and Australia suggests that SISs can have an important role to play in harm reduction. Dr M Webb, Vesion 1, April 2006 5 There is a need for well designed clinical trials of SISs in the UK. The performance of such trials will however be difficult. Dr M Webb, Vesion 1, April 2006 6